Hearth, Home, and Hardening Boundaries

What Christmas taught us to ignore

Hello Interactors,

It’s Christmas Eve, and it’s time for me to be the Debbie Downer. Actually (see, here I go), according to this telling of history, Christmas as we know it came about to squelch riotous buzzkillers. But I like to think I’m bringing “emodiversity” to the conversation. Merry Christmas!

CLOTHES WERE ALL TARNISHED WITH ASHES AND SOOT

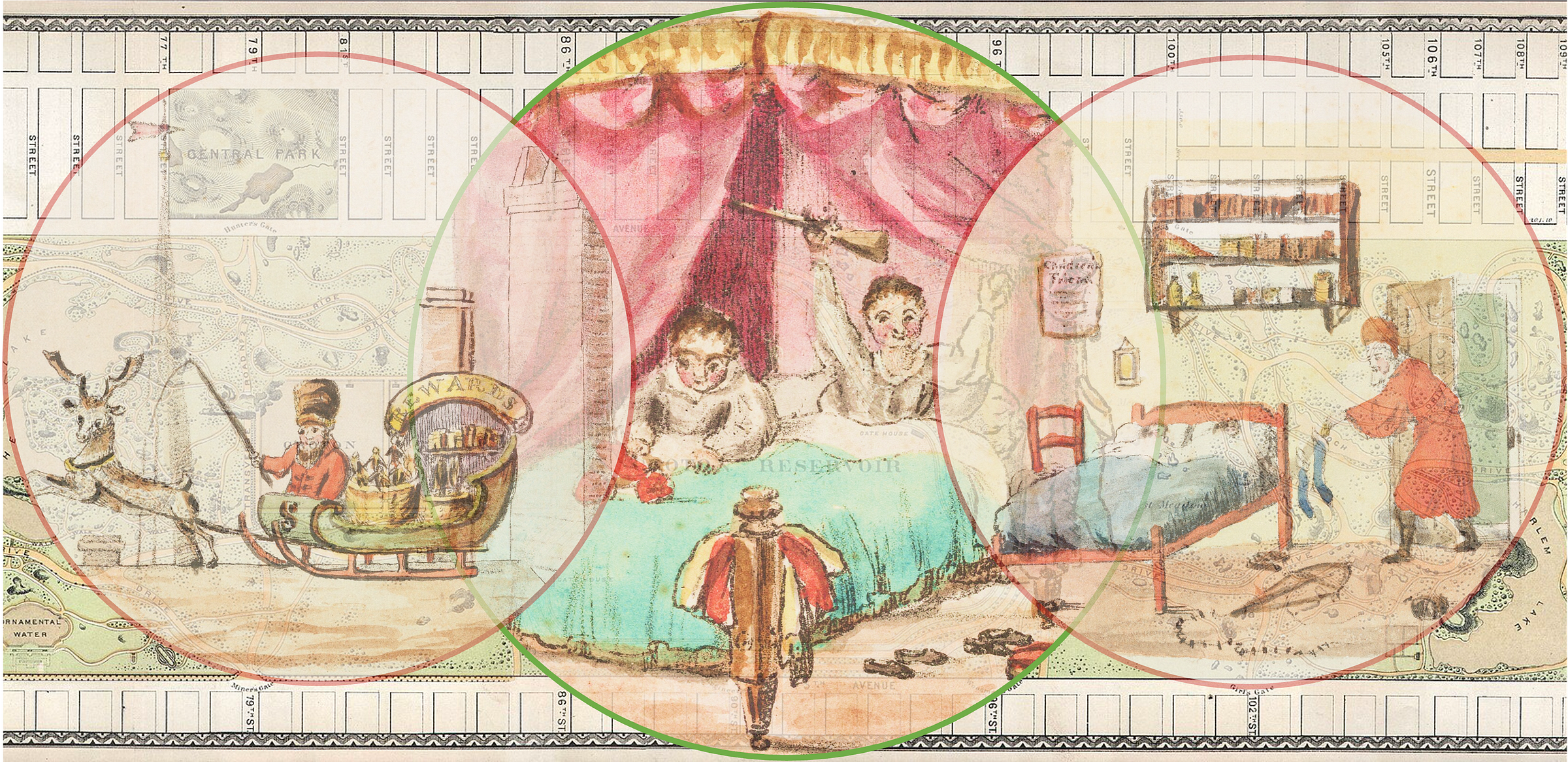

By now most American’s are familiar with this line from the popular Christmas eve story, Twas the Night Before Christmas: “He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot, / And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot.” That detail only works in a world where the home has become the stage for Christmas, and a fireplace has become the holiday’s boundary line. The soot is a tell. Someone crossed from “outside” to “inside” through the chimney. A home invasion but in a way that leaves the household intact, even charmed. That is not what Christmas looked like to many urban elites at the opening of the 19th century.

In the early 1800s, Christmas was not yet the big, shared civic and commercial event it would become. One reason it can feel “absent” in the record is that newspapers and polite society often treated it as a non-holiday. In that gap, the season was still shaped by older, rougher customs that included street noise, lots of drinking, and the annual testing of who had to give charitably and who could demand charity.

Urbanization sharpened those dynamics. In rural settings, winter misrule could be contained within face-to-face hierarchies. A landowner might tolerate (even theatrically join) a brief inversion of class rank by wassailing — a form of ritualized begging that was part party and part pressure valve. But in a fast-growing city, the relationship between “master” and “laborer” was increasingly anonymous, wage-based, and spatially segregated. When winter shut down water-powered industry and froze transport, the season could deliver sudden idle time and unemployment. These conditions made street customs louder, more mobile, and more threatening to property owners.

Wassailing and related practices operated like a seasonal toll. Visitors arrived uninvited, sang or jeered, and expected food, drink, or money. Refusal could invite ridicule, harassment, or worse…violence. In effect, it was a customary, once-a-year confrontation over surplus negotiating who had it, and who was obliged to share. In cities, with crowded streets and fragile policing, the same pattern could look less like tradition and more like extortion, or proto-riot.

So, the working class kept venting, but the rules of engagement changed. The urban elite did not generally “play along” with inversion the way a rural squire might. Instead, they built distance that was spatial (better doors, better neighborhoods), institutional (watchmen, courts), and moral (reform societies framing the poor as a disorder problem rather than a customary counterpart). What had been faint mockery — tinged with “you know what happens if you don’t pay” — could tip into confrontational street politics as the 1800s progressed.

In New York, John Pintard — a prominent civic organizer at the intersection of nostalgia, institution-building, and fear of the crowd — viewed the season as an intrusion. Pintard helped found the New-York Historical Society in 1804 — an explicit project of memory-making in a city whose demography and political power were changing fast.

In one widely discussed episode (December 1820), Pintard wrote of a stranger entering his house by mistake, and then described the street below — bands of celebrants “roaring” through Wall Street, shouting “No quarter!” and “Clubs! Clubs!” The point isn’t whether every shout was a literal threat; it’s that he heard it as one. For him, Christmas street sound became a class signal. The city had grown large enough that the “outside” could press against the parlor.

That fear sits next to his politics. New York’s 1821 constitutional changes broadened white male suffrage by removing (or reducing) property requirements for many voters—while simultaneously imposing tighter restrictions on Black voters. Elites like Pintard read this as the empowerment of a propertyless urban mass. In an 1822 letter to his daughter, he lamented “universal suffrage” and warned that New York would be “governed by rank democracy,” imagining the state “engulfed in the abyss of ruin.”

This is where “pauperism prevention” enters. Pintard helped launch the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism (founded in 1817), part of a broader early-19th-century push to reorganize charity and discipline the public presence of poverty. These groups tended to argue that indiscriminate giving encouraged begging, idleness, and drinking. They favored “rational” relief mechanisms that also functioned as behavioral control. They also tended to blame the poor rather than addressing structural issues like low wages and unemployment.

And the language of disorder was already racialized long before the 1820s. A New York newspaper complaint from 1772 (often re-quoted because it is so blunt and awkwardly familiar even today) grumbled about “the assembling of Negroes, servants, boys and other disorderly persons” in noisy street companies — gaming, drunkenness, quarrelling — disturbing the neighborhood. Whether in 1772 or 1822, this rhetoric does political work: it merges servants with Black people with “boys,” collapses leisure into vice, and turns street sociability into a public threat that justifies surveillance and control. (The Battle for Christmas)

Pintard’s nostalgia, then, wasn’t simply for “merrier” Christmases. It was for a social architecture in which elites could allow brief misrule without feeling that misrule might become rule. That is why memory projects and holiday-making mattered: if you can redefine what the season is, you can redefine who belongs in it — and where.

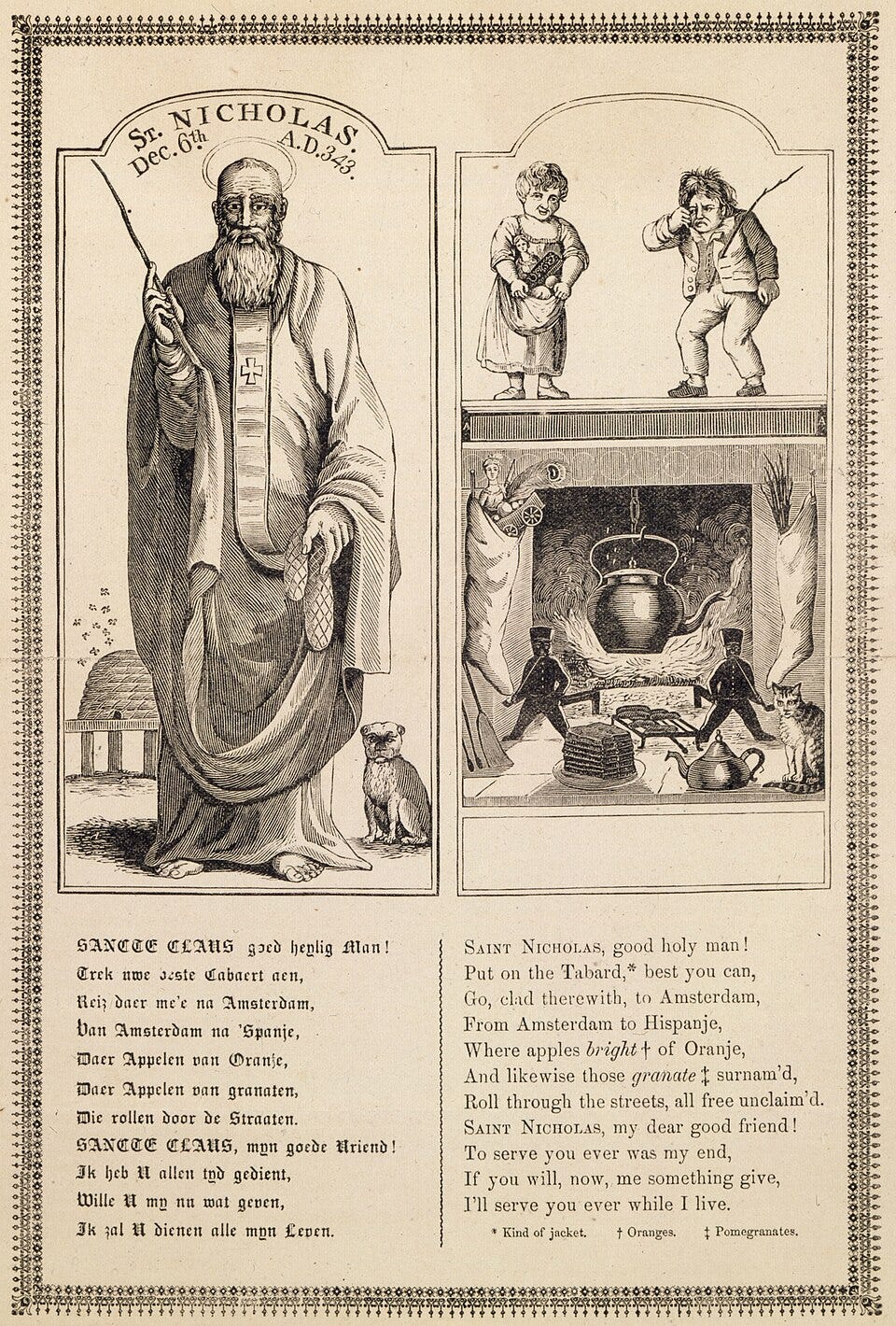

He did exactly that with St. Nicholas. For the New-York Historical Society’s St. Nicholas Day dinner in 1810, Pintard commissioned a broadside engraving (by Alexander Anderson) that visualized “Sinterklaus” (Saint Nicholas) as a Dutch-inflected moral judge: St. Nicholas holds both a purse (reward) and a birch rod (punishment), and the Dutch hearth scene includes one stocking filled with treats and another with the rod alone. The rod in the boy’s coat served as a reminder for the boy to behave. This is not yet the consumer version of jolly ol’ Santa. He’s a solemn saint, meant to domesticate behavior and tie New York identity to a selectively remembered “Dutch” past in a time when protestants were reluctant to give into festive celebrations.

WHAT TO MY WONDERING EYES SHOULD APPEAR

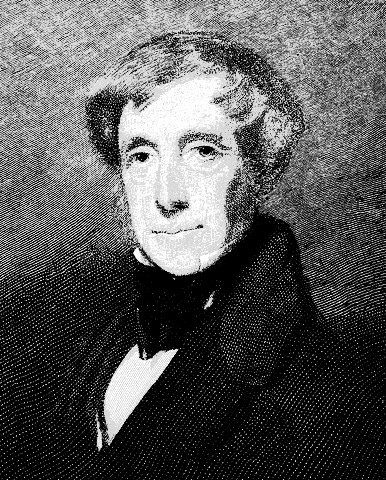

Into this mix of street disorder, elite fear, and civic nostalgia drops the poem that re-coded Christmas for the household: “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” What has since become known as The Night Before Christmas or Twas the Night Before Christmas. Traditionally dated to 1822 and first published anonymously in the Troy Sentinel in December 1823, it wasn’t until 1837 that real estate developer and bible scholar, Clement Clarke Moore, claimed authorship. The family of poet Henry Livingston Jr. claimed in 1900 that he authored the poem. By then, several sources claimed Moore as the author and it remains debated. Either way, the poem became a template not just for Santa’s look, but for Christmas’s social geometry that indeed reflected Moore’s own beliefs, and those in his social circle.

The poem’s genius is that it keeps the thrill of intrusion while neutralizing the threat. Something does arrive “on the lawn” with a “clatter.” (an image Moore lifted from his friend and Dutch revivalist Washington Irving — of Rip Van Winkle fame — in his book A History of New York.) A stranger does enter at night, but he is rendered as a manageable figure — “a right jolly old elf” — whose labor arrives as gifts, not demands. The earlier season’s confrontational exchange (give us drink, or we’ll make trouble) is displaced by an internal, child-centered economy. Children expect gifts because a benevolent visitor hands them out, and adults perform generosity by purchasing, stocking, and staging that gift. In other words, the social pressure of the street is replaced by the emotional pressure within the family.

Moore also takes the older St. Nicholas from Pintard material and sands off its sharp edges. The 1810 broadside’s rod, discipline, and judgmental ledger — good child/bad child — are central to the earlier imagery. But Moore’s St. Nicholas is “merry,” “droll,” “rosy,” “plump”: a pleasure-giver rather than a behavioral auditor. Even the class-coded “peddler” image is made safe — commerce without confrontation, work without resentment.

This mattered because New York itself was being remade — politically, spatially, and economically. And it was occurring at a pace that made old forms of deference unstable. The Commissioners’ Plan (authorized in 1807; published in 1811) imposed the rectilinear grid that would turn uneven land into legible lots, and future streets into future real estate. Simeon De Witt, the state surveyor general, was one of the appointed commissioners. The grid was not merely road geometry but a machine for converting terrain into property, and property into a mass market.

Moore’s own life sits inside that conversion. He was a landholder in Chelsea, tied to the Episcopal establishment, and later a professor at the General Theological Seminary, which came to occupy land he donated. He also publicly protested aspects of the city’s street-making regime (not because he hated profit — he developed and sold lots — but because he hated what the regime empowered. A city pushing a democratic, laboring future pushing north and west).

And all of it unfolded in a city whose scale was changing the meaning of “the people.” New York City’s population rose from about 33,000 in 1790 to more than 120,000 by 1820. This growth intensified crowd politics, amplified street sound, and made class encounter harder to contain inside older rituals of patronage.

What also cuts against the poem’s soft focus is the fact New York was still entangled with slavery. The state’s gradual emancipation laws, which started in 1799, culminated in final abolition taking effect in 1827. So the “domestic” Christmas being invented for respectable households sat alongside domestic labor practices — some waged, some unfree — whose inequities were not resolved by sentiment. Moore owned five slaves when he wrote his poem and was a fierce anti-abolitionist until he died in 1863.

Read this way, “A Visit from St. Nicholas” isn’t just a charming poem. It’s a settlement proposal. It tells the anxious propertied class they can stop answering the door to the seasonal banditti. You can stop treating the street as an annual moral debt. You’re your generosity inside and angled toward your children. Doing so will give you a Christmas that feels safe, private, and orderly. The soot stays on Santa’s clothes, not on your doorstep.

Two centuries later, we live inside the perfected version of that bargain. The threshold has multiplied into locked lobbies, gate codes, door cameras, cars, and two-factor authenticated login screens. Winter can be navigated from indoors with home deliveries, streaming, and remote work. The chimney may still work, but it sits alongside social systems that let comfort flow inward while the outside world stays outside.

Staying inside correlates with warmth, space, stability, and safety. For some, “cozy” is an aesthetic, but for others, home is overcrowded, unheated, temporary, or absent. The same season that promises private comfort produces public hardship. In the 1800s it may have led to street parties or near rioting, but now people are forced to sleep outdoors, ride buses for heat, and cycling through overcrowded shelters. The old drama of threshold returns. Some disappear deeper indoors while others are forced outward into exposure.

The demand persists, but it arrives differently. Where a crowd once sang at the door, the ask is quieter and easier to ignore or satisfy at a distance. A donation can be made without contact, without the discomfort that once made inequality undeniable. Meanwhile, the “friendly plebeian” returns as labor in the form of delivery at night, laboring in warehouses under quotas, or care worker moving between apartments. It’s the work that keeps the household cozy and warm and the property safe and sealed.

Fear has modernized too. Cameras, gates, hardened lobbies, private security, hostile architecture, and routine policing repeat an old logic. Keep disturbance away and keep need out of sight — especially when commerce depends on the appearance of abundance.

This is why the winter solstice matters as more than a quaint counter-holiday. Solstice is not a celebration of hardship but a reminder of shared constraint. Moore, Irving, Pintard, and their circle proved that “tradition” is not simply inherited — it can be authored. They selected what to remember, softened what to fear, and rearranged the season’s meanings until a new version of winter felt natural.

If they could rewrite the story in the image they preferred — quiet, orderly, domestic — then the story can be rewritten again, without so much nostalgia or spectacle. Not by romanticizing suffering, and not by outsourcing care to private sentiment, but by building ordinary kindness into public life. Can we envision warmer thresholds instead of hardened perimeters, tolerance for presence instead of reflexive removal, spaces where people can exist without buying something, and systems that reduce winter harm as a matter of course?

The point is not to recreate an older communal world. It’s to choose, deliberately, a winter ethic equal to the world we actually have. The night before Christmas should be one that makes warmth and belonging less conditional, and generosity less performative. Less a gift for you and me under the tree and more gifts for ye and thee as need be.

References

The Battle for Christmas. A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday. Stephen Nissenbaum. 1997

John Pintard. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Pintard

Clement Clarke Moore. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clement_Clarke_Moore

Here is the APA reference for that article:

LA Review of Books. (n.d.). Poems think they know ’Twas the night before Christmas. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/poems-think-know-twas-night-christmas/

Great historical perspective for a Christmas Eve read! Thanks.