Hello Interactors,

Welcome to 2022. Or, as my son likes to say, twenty-twenty also. Today we begin our winter journey through human behavior as it relates to the interaction of people and place. As we further divide, we seem to also be drifting apart. So I turned to one of our leading philanthropic philosophizing musicians, Bono, for the answer.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

BONO SCRATCHES

The holidays have a way of making you reminisce. I was thinking back 14 years ago when I met Bono at Microsoft just before the 2007-2008 holiday break. He was promoting his RED giving initiative and a small group of us in Windows were meeting with him and his team on ways to incorporate RED into Windows as a cross promotional scheme. Bono thought it especially relevant given we were in REDmond, Washington.

I was an early U2 fan. I bought their third album, War, on vinyl in 1983 when it first came out. So I brought it along to the meeting to see how Bono would react. As we filed into the Microsoft board room being greeted by members of the RED team and Bono, I was watching his eyes through his yellow tinted glasses. He immediately latched on to the album in my hand, walked over to me and said, “You just don’t see many of these.” And he took it from me as I followed him to the conference table. He asked me my name, pulled out his red pen and wrote on the back of the album cover, “It took 24 years but we finally hooked Brad. See you…” He then drew his signature profile of his long nose, glasses, and a straight smile and signed it, “Bono.”

He was shorter than I imagined. But genuine and endearing. He shared the space and time in that meeting with everyone. But, at the end, he couldn’t resist taking jabs at the Windows logo. “Look,”, he said. “I’m not a business person, I’m an artist.” He then stood up and approached the white board. He talked about how awful the Windows logo was. “Why is the Windows logo a flag?”, he asked. “It bothers me.” He then grabbed a pen and drew a simple four pane window and said. “See, a window. How hard can that be?”, he demanded. And sat down.

He had a point. And within a couple years, he got his wish. Pentagram, a design firm in New York, designed a new Windows logo. And with it came a new Microsoft logo that looks more like the sketch Bono made. But it turns out, as is often the case, even that idea was not new. Pentagram had proposed that same logo years before, but it was rejected.

But I admit, I was a bit distracted during his loquacious logo lecture. It was hard taking him seriously in his skin tight gold pants. He was distracted too. While Bono was pacing along the whiteboard with pen in hand, his other hand was routinely futzing with his crotch. He looked like a baseball player stepping out of the batters box to adjust his cup or scratch an itch. It’s not the image of a rock star you want lingering in your head.

I prefer to remember Bono as a 20 year old kid on MTV bellowing protest songs from the album he signed.

U2’s album, War, is noted for its harsh departure from their previous two albums, both musically and lyrically. They set out to tackle themes of war as Ireland had seen its fair share in his lifetime. Their biggest hit from that album, “Sunday Bloody Sunday”, leads in with drums resembling a military march and features the blending of physical and emotional impacts of war. It includes lines like, “The trench is dug within our hearts.” It goes on to address the apathy around war and how our defiance against it is lessened by the numbing of the everyday violence mixed with fictionalized versions on TV.

And it's true, we are immune

When fact is fiction and TV reality

And today, the millions cry

We eat and drink while tomorrow, they die

The song, “Sunday Bloody Sunday” refers to a particularly bloody conflict in 1972 called Bloody Sunday. On Sunday, January 30th, 26 British soldiers opened fire on unarmed protestors in Northern Ireland killing 13 on the spot. One other died later from wounds. Many of these 14 people were either fleeing or helping other injured civilians.

These lyrics are about the effects of Northern Ireland conflicts that had been occurring for more than two decades by the time U2 released this album. The conflicts occurred mostly in Northern Ireland over political and nationalistic opinions between two warring factions. On one side were Unionists and loyalists, who wanted Northern Ireland to remain in the United Kingdom, and on the other Irish Nationalists and republicans, who sought to abandon the United Kingdom to create a United Ireland. Those seeking to stick with the United Kingdom were mostly Ulster Protestants, and those seeking independence were mostly Irish Catholics which added further religious and historic dimensions to what the Irish called The Troubles.

GROUPIES

These two factions created what sociologists call in-groups and out-groups. In-groups are defined as “a social group to which a person psychologically identifies as being a member.” Out-groups are “social groups with which an individual does not identify.” It’s easy to imagine how these two groups in Ireland could formulate in-groups and out-groups along historical, social, religious, and political lines. And looking around today, it’s easy to spot scads of in-groups and out-groups all around us and around the world.

In many cases these attributes and divisions are real. In the case of the Irish conflict, who is a Protestant and who is a Catholic, for example, is empirically verifiable. But often times out-groups are created through fabrications of identity traits. They simply become reinforcing prejudicial stereotypes rooted in an underlying fear. Members of the in-group come to feel threatened and build elaborate cases for why the out-group should be feared.

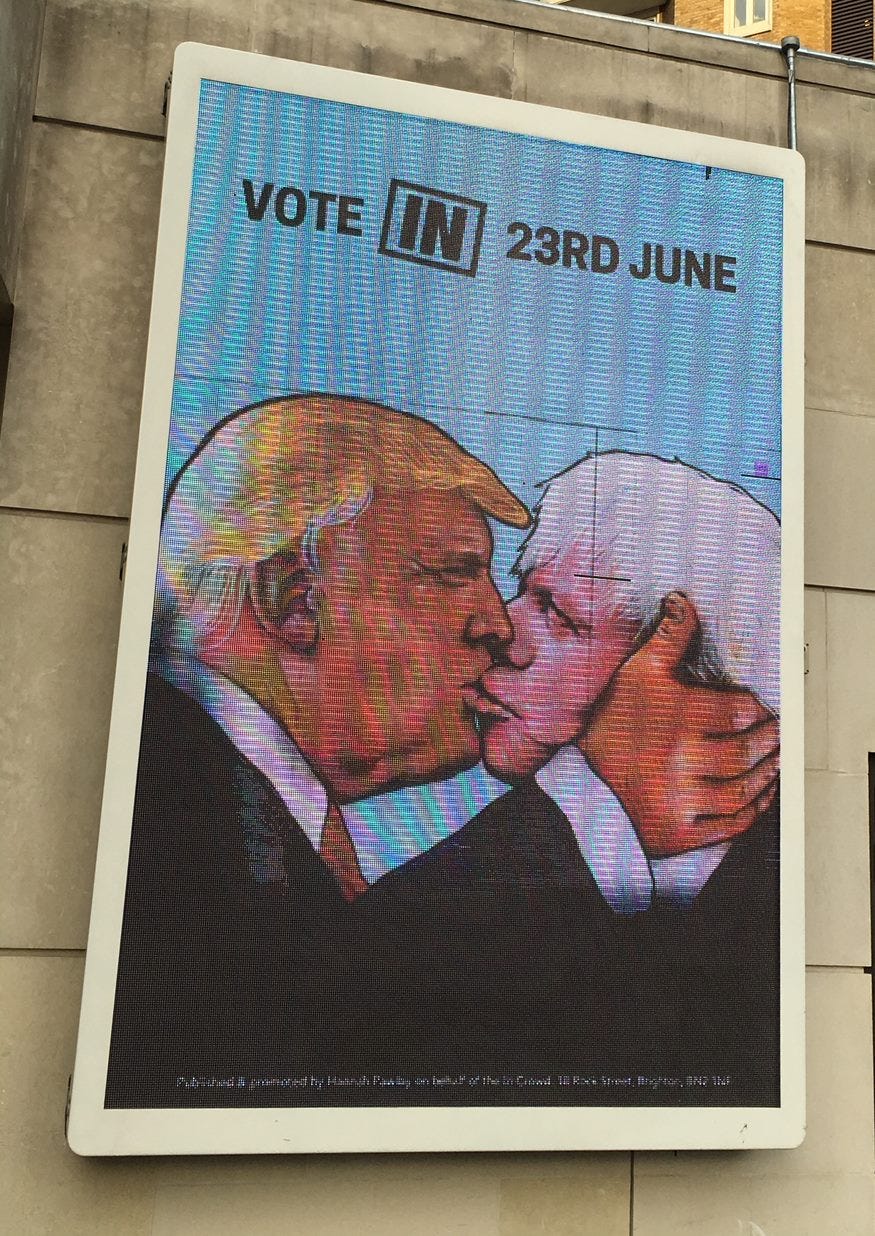

It happened in the United Kingdom with Brexit and in the United States with the swell of conservative in-group and out-group identification that Trump helped to solidify. It continues today on the topic of global warming. Many conservatives refuse to believe global warming is a fact. They fear making multi-national corporations accountable for environmental destruction would hurt the economy and America’s dominant position on the world stage. So they invent Anti-American ‘liberal’ out-groups and throw scientists, environmentalists and anyone who agrees with them into the groups. They then sprinkle combustible myths over the lot of them and then strike the match of Fox News and watch it burn.

Many sociobiologists, like the recently deceased E.O. Wilson, would argue these people are simply executing on a well established evolutionary strategy. They’re protecting their own in an act called kin selection. It’s defined as “the evolutionary strategy that favors the reproductive success of an organism’s relatives, even at a cost to the organism’s own survival and reproduction.”

When an in-group feels threatened, they turn to their members and seek protection while simultaneously turning their back on the out-group. Regardless of which group you’re in, you can’t help but feel threatened by some aspect of the effects of globalization. And so you turn to your in-group for comfort, protection, and strategies for survival.

E.O. Wilson extends this argument further to include group-selection theory. Where as kin theory is an individual evolutionary act singled out as favorable through natural selection, Wilson also argues the same can be applied to groups. Those groups that amass the largest in-groups come to dominate the progressively weakening out-groups.

It turns out these theories are hotly debated. Arguments against group-selection theory question how a group could possibly survive natural selection if they’re hellbent on self-destruction. It turns out, like the over reliance on the physical sciences to simplify economics, Darwinian ideas, while revolutionary and sound on their own terms, fail to extend to the complexities of the modern human psyche.

The intricacies in the balance or tension, for example, of selfishness and cooperation in socio-psychological interactions are unlikely to be explained simply through evolutionary histories. Sociologist, Brian Castellani, studies the complexities of place and health and he reminds us that,

“as recent developments in the complexity sciences have made rather clear (e.g., Byrne & Callaghan 2013; Capra & Luisi 2014), psychological existence and more widely social psychology and socio-anthropological existence are different forms of emergent self-organization, which require interdisciplinary understanding beyond just the biological sciences or physics or any such attempts at reductionism.”1

E.O. Wilson would likely agree as these are themes he covers in his 1998 book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. It’s there that he concludes,

“The human condition is the most important frontier of the natural sciences. Conversely, the material world exposed by the natural sciences is the most important frontier of the social sciences and humanities. The consilience argument can be distilled as follows: The two frontiers are the same.”2

Humans are social animals. We survived and evolved over hundreds of thousands of years by dealing with the tensions and conflicts between individuals and groups with whom they lived. Castellani writes,

“given that we are resolutely social organisms, it is better stated that our human capacity for altruism, cooperation, competition, aggression, and social commitment are, for the most part, a function of the fact that we have evolved, as a species, in highly complex social groups – group selection true or not.”3

He continues,

“…the psyche’s evolution did not produce the tension between individuals and civilization; instead, the psyche’s evolution is a function of this tension.”4

REDUCE, REUSE, RECYCLE; PREJUDICE, ABUSE, BUSINESS CYCLE

Success, or happiness, of an individual or a group, in evolutionary terms, most likely came down to a realization that in order to survive one must choose to sacrifice. Any of us who ever played on a team, a band, or worked in a group knows that collaboration through cooperation can only work with individuals who make certain sacrifices for the team. Hence the old adage, “there is no ‘I’ in team.”

We indeed are hardwired, evolutionarily speaking, to act in our own self interest to survive against an imminent threat. Fight or flight instincts are real. Yet we are equally hardwired to choose self-sacrifice. If such a sacrifice is deemed too extreme, we have the ability to choose to leave the group. Such a choice in the early days of homo sapiens came with its own risk; the group may not survive nor may you. The odds of survival are in favor of the natural forces of both local and global societies. These odds advantage the survival of groups over the survival of individuals thus discouraging such selfish behavior.

And yet it still happens. We need only look at voluntary military service as evidence of self-sacrifice for the betterment of the group. And the draft is a great example of an in-group, the government, sacrificing individuals for the survival of the larger group, the country. But such cases are rare, especially with regards to heroes, relative to the general population. But there are smaller, less drastic altruistic sacrifices people make everyday. It’s a group of people that form their own in-group.

This in-group makes small sacrifices for the betterment of the planet; they recycle, walk, bus, and cycle, drive less, buy less, fly less, downsize, or simply conclude they must grow their own food. These actions are also driven by fear of the effects of globalization. Think globally, act locally. These people perceive a global threat and fear that if they don’t make some sacrifices for the good of the group, they, nor the group, will survive.

But such sacrifices are only effective at a scale larger than one’s own home, business, or even city. It needs to scale globally. We know how to scale for powerful impact. The French philosopher, Michel Foucault, developed theories on the relationship between power and knowledge. He noted two different forms of technologies of power. (He’s using the term technology broadly to mean the practical aims of changing the human environment) First there are the technologies of self which is the power to make your own decisions. The second are the technologies of power and government. For example, even if you decide not to wear a mask in public, institutions hold the power to oblige you to do so.

We are pressured individually by our in-groups, or defiant in opposition to an out-group, to behave a particular way. Yet, overlaying it all – even in the presence of fierce hatred and animosity between groups – are human invented policies, procedures, laws, treaties, and obligations that find a way to mend, connect, skirt, or correct the differences between groups. Technologies of power.

And even at a psychological level, we posses as humans innate concerns for our global commitment in our day-to-day lives. Technologies of self. Sigmund Freud, in his book titled Civilization and its discontents, talks of roles that Brian Castellani generalizes as “conforming,” “cooperative,” “cohesive,” “common identity,” and “let’s-work-together-and-figure-out-how-to-get-along.” These are the very roles civilizations have relied on to survive and thrive throughout our existence.

History has a pretty good track record of societies and governments coming together despite our differences. The outcomes are not perfect, but we made it through the Cold War, civil rights movements globally, and ongoing negotiated tensions between the United States and China or even North Korea. The social-psychologist Anselm Strauss summarizes it like this,

“The negotiated order on any given day could be conceived of as the sum total of the organization’s rules and policies, along with whatever agreements, understandings, pacts, contracts, and other working arrangements currently obtained. These include agreements at every level of organization, of every clique and coalition, and include covert as well as overt agreements.”5

Any unhappiness or fear we may feel is of our own doing. And we’ve invented social super structures, technologies of power, to address them while knowing full well they also perpetuate our unhappiness. It’s what makes people want to retreat to a simpler past. Some wish to escape to a primitive natural oasis as Thoreau did around Walden Pond while others want to retreat, like Trump does, to the 50s and 60s as a way to “Make America Great Again.”

BONO IS NO HIPPIE

Thoreau discovered retreating to nature and isolating himself from society did not yield the happiness he expected. He too, after all, was a social animal. And while many in America, especially White men, reflect nostalgically on how much better it was for them in the 50s and 60s they forget, or don’t care, to remember it was a time of rampant spousal abuse. Wife beating was not made illegal in all states until 1920. It wasn’t until the 1970’s women’s movement that it got the attention it deserved. The term ‘domestic violence’ didn’t appear until 1973.

In 1930 Freud addressed our attraction to the chimera of nostalgia by observing “that what we call our civilization is largely responsible for our misery, and that we [believe we] should be much happier if we gave it up and returned to primitive conditions.” Considering he wrote this at a time when Nazism and Stalinism was on the rise, it’s clear his observations would have been very real.

In 2018, the British comparative religion writer and former Roman Catholic sister, Karen Armstrong, noted

“that such nostalgia remains the primary motivator for the rise in religious, cultural, and political fundamentalism throughout the world—all a reaction to the perceived “ills” and “inequalities” of globalization and global civil society, which these nostalgic thinkers “read” as resolutely global, secular, elitist, bourgeois, liberal, harmful, and blasphemous.”6

It’s not hard to identify such in-groups: nationalist movements in Europe, Muslim Fundamentalists and extremists, and the Alt-Right movement in America – which is dangerously neighboring the in-groups of the Christian right, the Tea Party, and increasingly the majority of the Republican party.

But there are also groups who want to move toward a more global civil society. They see the tolerance and blending of religions, cultures, and traditions as a way to advance the global community. These are people who live in the now and believe advances in income inequality, race relations, gender spectrum awareness, health and wellness, and reducing global warming can yield a better future for all. And they embrace the global network society introduced through the rapid advancement of the information age.

As Brian Castellani says, “at no previous point in our history of anatomically modern Homo sapiens have humans had the capacity to engage in, perpetuate, or share their social commitments (global or otherwise) on such a global scale.”

And while some dream of a utopian network society – a massive global in-group – any dip into social media will tell you it’s unlikely anyone will get that many people to agree on a set of binding principles and sacrifices.

But the global network society has proven effective at rallying local acts of defiance that lead to compromise. The worldwide BLM movement is the most immediate example. And as unpleasant as it is, defiance in the spirit of altruistic progress toward a better future may be our only choice.

It is this very progress that defines an out-group in the eyes of conservatives. The ills of globalization, in their eyes, are the progression, recognition, release, and rise of the historically oppressed. They invent scapegoats in the form of brown skinned immigrants or encroaching Asian wealth and dominance. Many in this in-group fear the grip of the mythical White Anglo-Saxon Protestant slipping away and yearn for a nostalgic Western dominance that they believe their Christian God ordained them to execute.

Progressives define conservatives as an out-group. They feel the ills of globalization are the result of over-exploitive capitalistic dominance wrapped up in Western expansionist dogma. Their scapegoats are business men, White male politicians, and toxic masculinity. They fear an allegiance to ever rising GDP will result in a collapse of natural resources and increasing climate instability that threatens the existence of all living beings. Many in this in-group yearn for a nostalgic return to local living and simpler lives that depend less on the globalist infrastructure of over-exploitive capitalism.

Castellani believes it comes down to this,

“As such, in the face of this misery, we really only have two options: bring peace and happiness into the world through civil disobedience and brutal compromise (both within ourselves and in relations to our bodies, nature and others); or allow our fear of the global to draw us into nostalgic retreat, which often quickly turns our best dreams and intentions into global nightmares.”7

Track 4 on U2’s album, War, is a piece entitled “Like a Song.” It’s one of the least performed songs by the band, but its lyrics speak to today’s divided groups. In Verse Two Bono nods to in-group signaling that can trigger nostalgia while also calling us to rebel against our divisions, seek connections with others through agreeable terms, and strive to help one another.

And we love to wear a badge, a uniform

And we love to fly a flag

But I won't let others live in hell

As we divide against each other and we fight amongst ourselves

Too set in our ways to try to rearrange

Too right to be wrong, in this rebel song

Those are some wise words from a group of 20 year old wannabe punk rockers. And after all these years, Bono continues to acknowledge that the struggles for peace and justice, while motivated by altruism, can only happen through defiance, resistance, and compromise. It is, after all, the natural order of complex systems.

In a 2015 Rolling Stone interview he’s quoted as saying,

“When you get bleak about things and think, Gosh, is there an end to this? Yeah, there is, it just takes lots of work, lots of time. I was never a hippie— I’m punk rock, really. I was never into: “Let’s hold hands, and peace will come just because we’ll dream it into the world.” No, peace is the opposite of dreaming. It’s built slowly and surely through brutal compromises and tiny victories that you don’t even see. It’s a messy business, bringing peace into the world. But it can be done, I’m sure of that.”8

E. O. Wilson. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. 1998.

Castellani, Brian (2018). The Defiance of Global Commitment: A Complex Social Psychology. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Share this post