Hello Interactors,

This week, four strange bird encounters landed in my lap — three in real life, one on my screen. First, a crow tore through the bushes in our yard chasing a frantic nuthatch. Moments later, I spotted two more crows feasting on roadkill just outside our house. Then, while walking with my wife, we watched four ducks in hot pursuit of another, flapping furiously down the street — some kind of aerial turf war. And finally, scrolling through my feed, I stumbled on a paper describing a Cooper’s Hawk hacking the city’s traffic system to hunt smarter. After all that, I tried seeing cities as a bird might. So I wrote as one.

HISS, HUM, HUNT

I first sense the city as vibration. Before sun rays even breech the branches, a hiss of car tires emerge; street lamps click off; somewhere a garage door rumbles open. Each resonance strikes the hollow chambers of my bones like sonar. It’s a sketch of distance, density, and direction. This all makes perfect sense to me even though I am just a kid. A juvenile Cooper’s Hawk — Accipiter cooperii — yet the human-made maze below me is as legible to me as the nest I left barely two winters ago. What follows, in human words, is a recount of one day’s hunt. I hope to demonstrate what humans regard as intelligence, innovation, and enterprise exists in a single act of predation.

DANCING WITH DATA AT DAWN

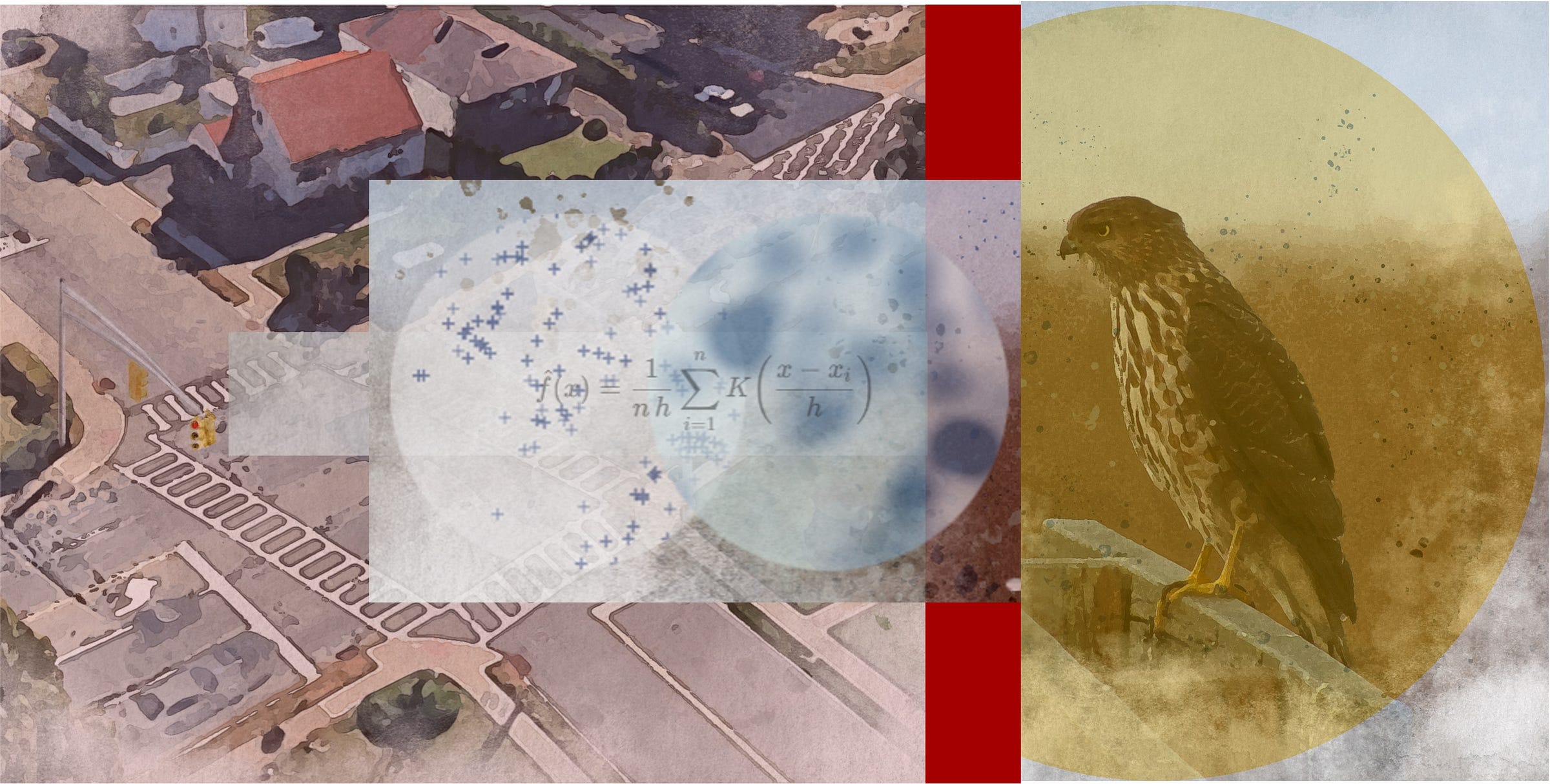

Perched on a gray mast of the Main and Prospect traffic light, I begin to render the scene. My basemap is no pixel grid glowing on some screen across town; it is a topological organ in my scull. Topology matters when a lamppost sits one maneuver away from the porch roof, which is one glide away from the dumpster rim. My so-called ‘bird brain’ calculates dynamic flows of probability. One flip of a traffic light, a garbage truck rolls by, and that gust of wind changes direction. My internal map pulses between “larger” when prey likelihood rises and “smaller” when likelihood falls.

As I gaze out above the east-west avenue, a slipstream peels off the 7AM wave of commuters. I spot a sparrow in a vortex that spirals from the garbage truck’s wake at 07∶13. That acoustic shadow beneath that florist’s van is one place I could pass unseen. But is a sparrow worth it?

What I am doing — unknown even to myself — is what spatial scientists call real‑time kernel‑density estimation. At any point on a simple 2D path I can plop a small mathematical bump — a kernel. I can then reason about the density mapped below me by stacking up every bump’s contribution at a particular spot. That once scatter of points on a map morphs into a smooth curve that shows where meaningful observations truly cluster. I continuously weight a landscape of pigeons, cyclists, and idling SUVs by situational context rather than simple Euclidean distance.

Complexity geographer David O’Sullivan calls this kind of adaptive map a narrative model — a story the system tells itself so it can keep acting.1 My mental basemap obeys what is adjacent to what on this map. After all, a three‑meter hedge is more impenetrable than thirty meters of empty air; therefore straight‑line distances can lie and deceive. When humans try to simplify distances by saying, ‘as the crow flies’, they have no idea what they’re leaving out.

BRAKES BUILD BARRICADES

At 07∶26 a stainless‑steel button is pressed; I hear the relay’s metallic click 3.2 seconds before the little white pedestrian blinks alive. I am perched here because I anticipated this poke by pedestrians on their morning commute. Vehicles will now queue as these bi-peds spill into the cross walk. The stacked metal boxes of steel, rubber, and plastic will form a barricade forty meters long…potentially.

Brake‑lights align into a pulsing crimson corridor whose half‑life I have calculated and averaged across nineteen previous dawns. Humans call the coming congestion a nuisance, but I call it camouflage. For twenty‑two seconds the asphalt canyon’s turbulence drops below an acceptable range. I can now hover as if among cedars.

A scientist has been watching from the opposite curb. They will soon begin recording this trick in their field book as so: a hawk anticipates the signal pattern and times its dives to the red‑phase distribution of brake lights.2

Because most queues are short, but occasionally very long, I have to be careful to time this properly. If I dive for prey based on the overall mean of the lineup, I will arrive while half the cars were still rolling to a stop — dangerous. So instead, I consider just the top-10% longest lines. Scientists marvel that I learned this algorithm in a single winter. I marvel that they need calculators to compute it.

ZEBRA STRIPE SLALOM STRIKE

I drop. The scent of hot rubber folds swirls with the cedar‑resin on my breast feathers as the warm air fills my plumage. The slowing bumper of a school bus becomes a landing spot — a moving parapet. Fresh into the dive, the thermoplastic zebra stripes flash white‑white‑white like a stroboscopic speedometer. None of this was made for me, yet every dimension matters for my survival. The curb‑to‑planter setback of 0.9 meters sets my glide angle; the bollard spacing — installed last year to calm e‑scooters — creates a slalom that funnels starlings toward an ornamental plum in a front lawn.

Urban design handbooks invoke words like livability and placemaking, as if these geometries were some kind of neutral toolkit. But for me, in the instant before impact, this curb‑to‑planter setback, this bollard slalom, adjudicates more than legal fiction — it means life and death.

Urban forms may look passive, yet every angle, radius, and dwell time means someone has won and someone has lost — wide curb radii speed cars through a right-turn but lengthen the crossing exposure for a toddler. Urban geometry is power cast in concrete; it never clocks off, and is both political and ecological: a three‑second refuge for a starling is a three‑second targeting solution for me.

FORCE AND FEATHERS FACES FEEDBACK

Impact. Feathers erupt like dark gray confetti. The starling crumbles under thirty‑four newtons of closing force — about the weight of a brick slammed into its ribcage. While I mantle the prize, a more philosophical bird might wonder: Who authored this death? Was it my neuromuscular burst alone? Or the person whose fingertip initiated a forty‑second cascade of stopped traffic? Or the traffic engineer who — chasing level‑of‑service targets — extended the red phase by six seconds last fiscal year?

Philosophy of science warns against naïve linear causation; urban events rarely run in neat A → B lines. Herbert Simon, writing on complex systems, described cities and organisms as “nearly decomposable hierarchies,” where slow, macro‑scale layers — like signal‑cycle regulations, curb geometries, and commuter habits — set the boundary conditions within which rapid micro‑events unfold.3 My talon snap and a starling’s dodge happen inside those higher‑order constraints, even as countless such micro‑acts, in aggregate, keep the larger structure of life humming along.

My strike, therefore, is a city‑scale phenomenon folded into tendon and keratin — street grids, signal cycles, and global supply chains compressed into one ballistic gesture. In the metallic tang of blood this mystery unfolds. I taste data: adipose fat tissue infused with fryer grease, feather sheaths dusted in brake dust, hormone ratios ticking through molt stage like seasonal code. Each swallow becomes a lab assessment — an unwitting biopsy of the urban food web — revealing how corn subsidies, restaurant waste, and airborne microplastics percolate up the trophic ladder. To devour a single starling is to audit the metabolic ledger of the Anthropocene, one protein strand at a time.

All of which reminds me that agency, mine, yours, the starling, is relational: the prey’s demise is over‑determined by a network whose nodes include asphalt viscosity — how a petrochemical blend modulates surface friction, drainage, and midday heat plumes — and municipal bond ratings that decide whether this intersection receives fresh pavement or another crosswalk. Chemistry, finance, and instinct co‑author every kill I make, and every step you take.

FIBERS, FOSSILS, AND FIRMWARE REFRESH

Dusk now drapes the mast in violet. Streetlamps flicker on; LED headlight arrays begin tinting the roadway cyan. Beneath the darkening asphalt, copper once meant for a clicking telegraphs now pipes broadband; beneath that, bricks baked when canals were high‑tech cradle those cables like red‑clay fossils. Media archaeologist Shannon Mattern argues that cities have always computed — tallying grain on cuneiform tablets, ringing bell‑tower hours to synchronize labor, routing mail through pneumatic tubes — only the substrates keep shifting, from clay and bronze to fiber optics and silicon.4 And trust me, nature was doing math long before humans claimed to invent it.

From my perch, epochs overlay transparently: timber palisades, horse drawn carriage tracks, fiber conduits. My hunting tactic is merely firmware patch v.2025 in a 5,000‑year old operating system. Your protocol tomorrow may be Li‑Fi pulses from a smart pole — a future where streetlamps won’t just illuminate, they’ll whisper streams of data in rapid-fire flashes — or the hiss of an autonomous shuttle that brakes at frequencies human reflexes never reach.

And you’ll be impressed with yourself. Meanwhile, I listen, map, and adjust — in my world here, survival goes to whoever learns faster, not whoever hits harder. Every fresh tactic buys a heartbeat of advantage, yet it also tightens the ratchet: the prey adapts, signals change, habits shift. Humans follow the same spiral — each smarter signal controller, each app‑driven reroute, plugs one gap while opening two more, slipping us all a step deeper into the city’s endless, restless loop.

OF DASHBOARDS AND DAGGER-WINGS

Humans may obsess over their dashboards and digital twins, yet a hawk that weighs less than a laptop already runs a live cognitive twin of the urban systems you built. Your impressed with monthly model updates while my model is updated at wingbeat resolution. If Homo sapiens hope to build a resilient future they might start where I perch: by listening for weak signals, mapping contingencies as well as coordinates, and recognizing that every curb, click, and feather participates in these nested conversations of forces.

The next time you press that crosswalk button and that electromechanical relay inside the signal‑control box snaps the circuit closed, ask not only whether it is safe to cross but what other intelligences have read that clue before you.

Meet us in the hush of those red taillights — inhabit that brief, engine‑silent interstitial where the white pedestrian man shines — then test what flickers in your own peripheral “bird brain”. Listen for the thin rustle of variables you once called noise; trace how a single press of that button ripples through nerves, budgets, buildings and beaks. Hold the silence long enough to notice how even I, a vicious dagger‑winged stalker, leave scraps for ground‑feeders and vacate a block after one clean kill so others may eat. If you can rest in that hush without lunging for your phone or some manically measured meaningless metric, you may begin to practice reciprocity — paring appetite to need, letting leftovers seed the next cycle — while stalking your own assumptions with the same taloned precision I bring to feather and flesh.

O’Sullivan, D. (2004). Complexity science and human geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers.

Dinets, V. (2025). Street smarts: A remarkable adaptation in a city-wintering raptor. Frontiers in Ethology.

Simon, H. A. (1962). The architecture of complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.

Mattern, S. (2017). Code and clay, data and dirt: Five thousand years of urban media. University of Minnesota Press.