Hello Interactors,

I’m back! After a bit of a hiatus traveling Southern Europe, where my wife had meetings in Northern Italy and I gave a talk in Lisbon. We visited a couple spots in Spain in between. Now it’s time to dive back into our exploration of economic geography.

My time navigating those historic cities — while grappling with the apps on my phone — turned out to be the perfect, if slightly frustrating, introduction to the subject of the conference, Digital Geography.

The presentation I prepared for the Lisbon conference, and which I hint at here, traces how the technical optimism of early desktop software evolved into the all-encompassing power of Platform Capital. We explore how digital systems like Airbnb and Google Maps have become more than just convenient tools. They are the primary architects of urban value.

They don’t just reflect economic patterns. They mandate them. They reorganize rent extraction by dictating interactions with commerce and concentrating control. This is the new financialized city, and the uncomfortable question we must face is this: Are we leveraging these tools toward a new beneficial height, or are the tools exploiting us in ways that transcends oversight?

CARTOGRAPHY’S COMPUTATIONAL CONVERGENCE

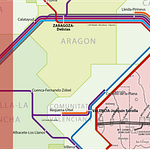

I was sweating five minutes in when I realized we were headed to the wrong place. We picked up the pace, up steep grades, glissading down narrow sidewalks avoiding trolley cars and private cars inching pinched hairpins with seven point turns. I was looking at my phone with one eye and the cobbled streets with the other.

Apple Maps had led us astray. But there we were, my wife and I, having emerged from the metro stop at Lisbon’s shoreline with a massive cruise ship looming over us like a misplaced high-rise. We needed to be somewhere up those notorious steep streets behind us in 10 minutes. So up we went, winding through narrow streets and passages. Lisbon is hilly. We past the clusters of tourists rolling luggage, around locals lugging groceries.

I had come to present at the 4th Digital Geographies Conference, and the organizers had scheduled a walking tour of Lisbon. Yet here I was, performing the very platform-mediated tourism that the attendees came to interrogate. My own phone was likely using the same mapping API I used to book my AirBnB. These platforms were actively reshaping the Lisbon around us. The irony wasn’t lost on me. We had gathered to critically examine digital geography while simultaneously embodying its contradictions.

That became even more apparent as we gathered for our walking tour. We met in a square these platform algorithms don’t push. It’s not “liked”, “starred”, nor “Instagrammed.” But it was populated nonetheless…with locals not tourists. Mostly immigrants. The virtual was met with reality.

What exactly were we examining as we stood there, phones in hand, embodying the very contradictions we’d gathered to critique?

Three decades ago, as an undergraduate at UC Santa Barbara, I would have understood this moment differently. The UCSB geography department was riding the crest of the GIS revolution then. Apple and Google Maps didn’t exist, and we spent our days digitizing boundaries from paper maps, overlaying data layers, building spatial databases that would make geographic information searchable, analyzable, computable. We were told we were democratizing cartography, making it a technical craft anyone could master with the right tools.

But the questions that haunt me now — who decides what gets mapped? whose reality does the map represent? what work does the map do in the world? — remained largely unasked in those heady days of digital optimism.

Digital geography, or ‘computer cartography’ as we understood it then, was about bringing computational precision to spatial problems. We were building tools that would move maps from the drafting tables of trained cartographers to the screens of any researcher with data to visualize. Marveling at what technology might do for us has a way of stunting the urge to question what it might be doing to us.

The field of digital geography has since undergone a transformation. It’s one that mirrors my own trajectory from building tools and platforms at Microsoft to interrogating their societal effects. Today’s digital geography emerges from the collision of two geography traditions: the quantitative, GIS-focused approach I learned at UCSB, and critical human geography’s interrogation of power, representation, and spatial justice. This convergence became necessary as digital technologies escaped the desktop and embedded themselves in everyday urban life. We no longer simply make digital maps of cities and countrysides. Digital platforms are actively remaking cities themselves…and those who live in them.

Contemporary digital geography, as examined at this conference, looks at how computational systems reorganize spatial relations, urban governance, and the production of place itself. When Airbnb’s algorithm determines neighborhood property values, when Google Maps’ routing creates and destroys retail corridors, when Uber’s surge pricing redraws the geography of urban mobility — these platforms don’t describe cities so much as actively reconstruct them. The representation has become more influential or ‘real’ than the reality itself.

This is much like the hyperreality famously described by the French cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard — a condition where the simulation or sign (like app interfaces) replaces and precedes reality. In this way, the digital map (visually and virtually) has overtaken the actual territory in importance and impact, actively shaping how we perceive and interact with the real world.

As digital platforms become embedded in everyday life, we are increasingly living in a simulation. The more digital services infiltrate and reconstitute urban systems the more they evade traditional governance. Algorithmic mediation through code written to influence the rhythm of daily life and human behavior increasingly determines who we interact with and which spaces we see, access, and value. Some describe this as a form of data colonialism — extending the logic of resource extraction into everyday movements and behaviors. This turns citizens into data subjects. Our patterns feed predictive models that further shape people, place…and profits. These aren’t simple pipes piped in, or one-way street lights, but dynamic architectures that reorganize society’s rights.

LISBON LURED, LOST, AND LIVED

The scholars gathered in Lisbon trace precisely how digital platforms restructure housing markets, remake retail ecologies, and reformulate the rights of humans and non-humans. Their work, from analyzing platform control over cattle herds in Brazil1 to tracking urban displacement, exemplifies the conference’s focus: making visible the often-obscured mechanisms through which platforms reshape space.

Two attendees I met included Jelke Bosma (University of Amsterdam), who researches Airbnb’s transformation of housing into asset classes, and Pedro Guimarães (University of Lisbon), who documents how platform-mediated tourism hollows out local retail. At the end of the tour, when a group of us were looking to chat over drinks, Pedro remarked, “If you want a recommendation for an authentic Lisbon bar experience, it no longer exists!”

Yet, even as I navigated Lisbon using the very interfaces these scholars’ critique, I was reminded of this central truth: we study these systems from within them. There is no outside position from which to observe platform urbanism. We are all, to varying degrees, complicit subjects. This reflection has become central to digital geography’s method. It’s impossible to claim critical distance from systems that mediate our own spatial practices. So, instead, a kind of intrinsic critique is developed by understanding platform effects through our own entanglements.

Lisbon has become an inadvertent laboratory for this critique. Jelke Bosma’s analysis of AirBnB reveals how the platform has facilitated a shift from informal “home sharing” to professionalized asset management, where multi-property hosts control an increasing share of urban housing stock. His research shows “professionally managed apartments do not only generate the largest individual revenues, they also account for a disproportionate segment of the total revenues accumulated on the platform”.2

This professionalization is driven by AirBnB’s business model and its investment in platform supporting “asset-based professionalization,” which primarily benefits multi-listing commercial hosts. He further explains that AirBnB’s algorithm “rewards properties with high availability rates,” creating what he calls “evolutionary pressures” on hosts to maximize their listings’ availability. This incentivizes them to become full-time tourist accommodations, reducing the competitiveness of long-term residential renting.3

The complexity of this ecosystem was also apparent during our Barcelona stop. What I booked as an “Airbnb” was a Sweett property — a competitor platform that operates through AirBnb’s APIs. This apartment featured Bluetooth-enabled locks and smart home controls inserted into an 1800s building. Sweett’s model demonstrates how platform infrastructure not only becomes an industry standard but is leveraged and replicated by competitors in a kind of coopetition based on the pricing algorithms AirBnB normalized.

In Lisbon, my rental sat in a building where every door was marked with AL (Alojamento Local), the legal framework for short-term rentals. No permanent residents remained; the architecture itself had been reshaped to platform specifications: fire escape signage next to framed photos, fire extinguishers mounted to the wall, and minimized common spaces upon entry. It’s more like a hotel disaggregated into independent units.

Pedro Guimarães’s work provides the commercial counterpart to Jelke’s residential analysis, focusing on how platforms reshape urban consumption. His longitudinal study demonstrates that the “advent of mass tourism” has triggered a fundamental “adjustment in the commercial fabric” of Lisbon’s city center.4

This platform-mediated transformation involves a significant shift from services catering to locals to spaces optimized for leisure and consumption. Pedro’s data confirms a clear decline and “absence of Food retail” and convenience shops. These essential services are replaced by a “new commercial landscape” dominated by HORECA (hotels, restaurants, and cafes), which consolidates the area’s function as a tourist destination.(3)

Crucially, the new businesses achieve algorithmic visibility by manufacturing “authenticity”. They leverage local culture and history, sometimes even appropriating the decor of previous, traditional establishments, as part of “routine business practices as a way of maximizing profit”. The result is the “broader construction of a new commercial ambiance” where local food and goods are standardized and adapted to meet international tourist expectations.(3)

My own searches validated these findings. Searching for restaurants on Google Maps throughout Southern Europe produced a bubble of highly-rated establishments near tourist sites, many featuring nearly identical, tourist-friendly menus. The platforms had learned and enforced preferences, creating a Lisbon curated only for visitors. Furthermore, data exhaust from tourist movements becomes a resource for further optimization. Google’s Popular Times feature creates feedback loops where visibility generates visits, which reinforce visibility. The city becomes legible to itself through platform data, then reshapes itself to optimize what platforms measure.

The Lisbon government, while complicit, also shows resistance. Both scholars highlighted municipal attempts to regulate platform effects, including issuing licensing requirements for AirBnB, zoning restrictions, and promoting local commerce apps that compete with global platforms (e.g., Cabify vs. Uber). These interventions reveal platform urbanism can be contested. However, as Jelke noted, platforms evolve faster than regulation, finding workarounds that maintain extraction while performing compliance.

All through the trip, I felt my own quiet sense of complicity. Every ride we called, every Google search we ran, every Trainline ticket I purchased, fueled the very datasets everyone was dissecting. It’s an uneasy position for a critical digital geographer — studying problematic systems we help sustain. We are forced to understand these infrastructures by seeing. Can that inside view start seeking a new urban being?

CODE CRACKED CITIES. GOVERNANCE GONE

My conference presentation leveraged my insider vantage from three decades at Microsoft. I traced how these digital infrastructures have sunk into everyday life by reshaping labor, space, and governance. From early desktop software I helped to build to today’s platform urbanism, I showed how productivity tools became cloud platforms that now coordinate work, logistics, and mobility across cities.

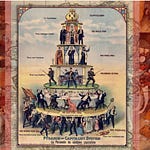

My framing used a notion of embeddedness through the lens of three key figures in the literature: Karl Polanyi, a political economist who argued that markets are always “embedded” in social and political institutions rather than operating on their own; Mark Granovetter, a sociologist who showed that economic action is structured by concrete social networks and relationships; and Joseph Schumpeter, an economist who described capitalism as driven by “creative destruction,” the continual remaking of industries through innovation and destruction. Platforms help mediate mobility, labor, commerce, and governance, even as they position themselves at arm’s length from the regulatory and civic structures that historically governed urban infrastructures.

This evolution is paradoxical. As platforms weave themselves into the operational fabric of urban life, they also recast the division of responsibilities between state, market, and infrastructure provider. Their ability to sit slightly outside traditional regimes of oversight allows them to appear as ready-made “fixes” for governments and consumers at multiple scales. Yet each fix comes with systemic costs, deepening dependencies on opaque, tightly coupled infrastructures and amplifying the vulnerabilities of urban systems when those infrastructures fail.

This progression reveals distinct phases of infrastructural transformation. It began in the Desktop Era (1980s-1990s) when I started at Microsoft and software was fixed to devices, localizing information work on individual desktops. Updates arrived episodically on physical media like floppy disks — users controlled when to install them. The shift to local area networks gave IT departments a hand in that control. Soon the Internet was commercialized which fundamentally altered not just how software circulated but how it was installed and updated. How it was governed. What once required user consent — inserting a disk, clicking “install” — became silent, automatic, and infrastructural. Today’s cloud services and IoT extend this transformation, embedding computational governance into vehicles, supply chains, and bodies themselves.

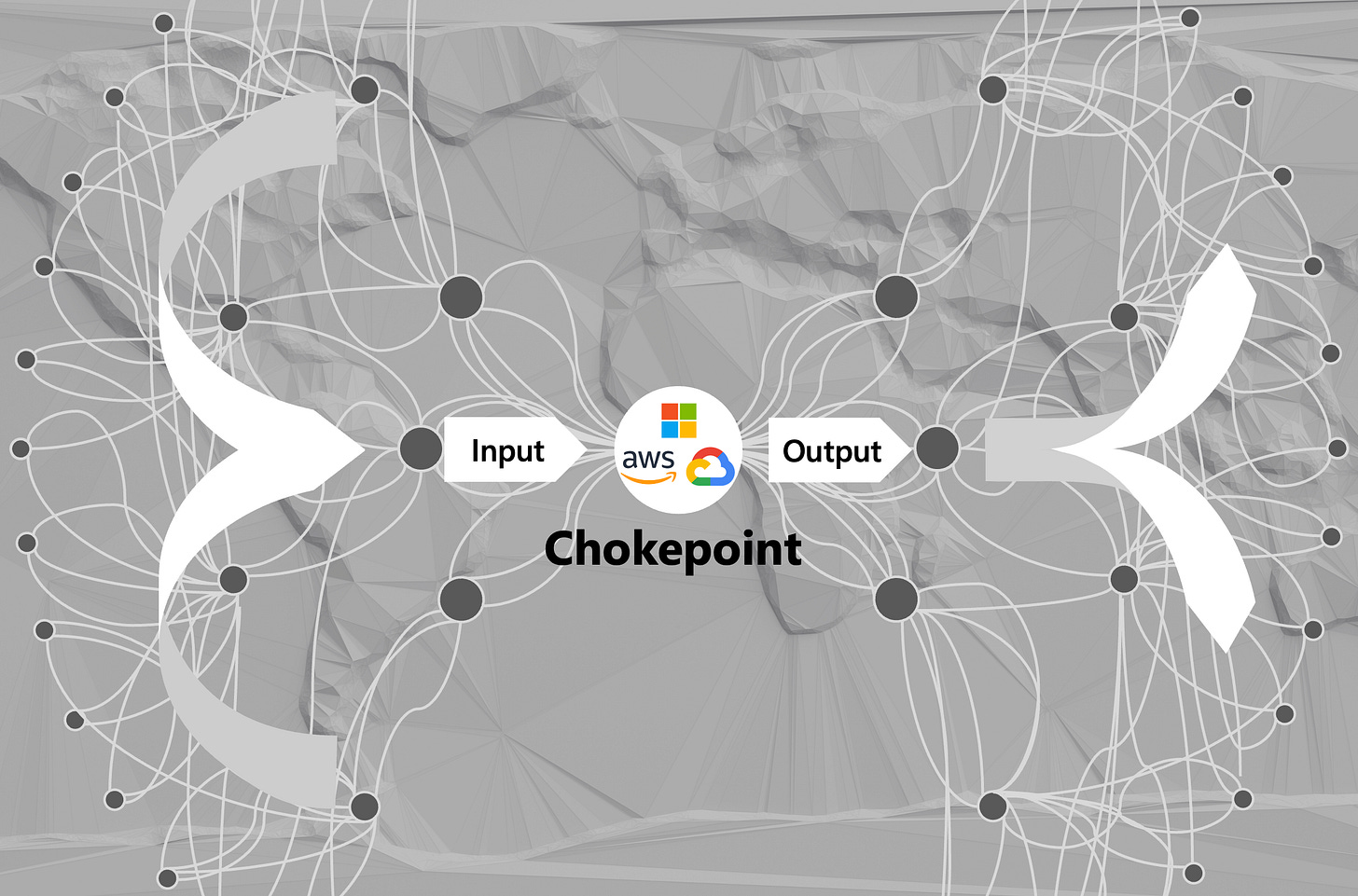

This progression reveals distinct phases of infrastructural transformation. The Desktop Era (1980s-1990s) embedded information work in individual devices — the fix was productivity, the limit was scalability. The Network Era (1990s-2000s) transformed software into continuous services — the fix promised seamless coordination, the exposure was infrastructural dependency. The Platform Era (2000s-2010s) decoupled software from devices entirely through APIs and cloud computing — the fix was coordination at scale, the cost was asymmetric control. The current IoT and Surveillance Era embeds platform logic in everyday urban environments — the fix is pervasive coordination. This creates a total dependency on opaque infrastructures provided primarily by three companies: Google, Amazon, and Microsoft. This chokepoint is what contributes to global vulnerability and cascading failures.

Recent large-scale cloud incidents, such as the latest AWS outage in Virginia in October — a week before the conference — make this evident. When a single region fails, payment systems, logistics platforms, and mobility services stall simultaneously. This pattern echoes an earlier cloud-network outage in 2021, in the same Virginia region, that effectively took much of Lisbon offline for hours, disrupting everything from transit information to local commerce. In both cases, what looks like flexible, placeless digital infrastructure turns out to be highly geographically concentrated and deeply embedded in local urban systems.

And yet, in nearly every case, these platforms really do operate as fixes at many different geographical scales. For capital, they open new rent-extraction terrains. For workers, they provide precarious income patches through part-time gig work. For users, they deliver connectivity and convenience. But a paradox emerges. Those same apps include affective hooks: user interfaces offering intermittent rewards — dopamine hits stemming from posts, likes, and ratings — embedded within endless, ad-riddled feeds. For cities, they promise smooth, efficient solutions to chronic problems. Yet as my presentation argued, these fixes are mutually reinforcing, binding participants into infrastructures of dependency that appear empowering while deepening exposure to systemic risk.

The paradox is clearest in places like the Sweett apartment in Barcelona. For users, it’s frictionless: Bluetooth locks, smart controls, and seamless check-in. For Sweett it’s all running on AirBnB’s own APIs even as they compete with AirBnB. For locals, the same infrastructure can help homeowners supplement income by renting a room, but it mostly converts affordable real estate into a short-term rental market. This drives up values, rents, and displacement. Platform standards like this spread until they feel inevitable. The logic embeds so deeply in the housing system that not optimizing for transient guests starts to seem irrational. Eventually, alternative futures for the neighborhood become hard to imagine and politically unviable.

What distinguishes digital platforms from earlier infrastructural transformations is their selective embeddedness. At the micro scale, interfaces shape conduct through programmable boundaries. At the meso scale, standards lock institutions into ecosystems. At the macro scale, chokepoints concentrate control in firms whose decisions cascade globally. Across all scales, platforms govern without being governed. They embed coordination while evading accountability.

The conference made clear that digital geography has fully evolved from my days studying ‘computer cartography’ in the 80s. It’s scaled to meet a world organized by the infrastructures I went on to help build. We are no longer observing digital representations of space. We’re mapping out the origins of a new way of thinking about space using algorithms. My tenure at Microsoft, spent building tools that would transform into embedded, governing platforms, was a preview of the world we now inhabit. This is a world where continuous deployment has become continuous urban reorganization. The silence of the automatic software update metastasized into the silent, pervasive governance of the city itself.

Lisbon, then, is not merely a case study but a dramatic staging of hyperreality. The Alojamento Local (AL) sign outside our Lisbon apartment door is not a description of a short-term rental; it is a code enforced reality optimized for a tourist’s online profile. The digital map, our simplified version of reality, has not just overtaken the actual territory; it now precedes it, dictating its function and challenging its original meaning.

This convergence leaves the critical digital geographer in an inherently unstable ethical position. Studying problematic systems while structurally forced to sustain them requires critiquing the data exhaust our own movements and decisions generate.

This deep understanding of digital platforms effects, gained from the trenches, is an asset. How else would this complex entanglement get revealed? It begs to move beyond just observing platform effects to articulating a collective response to this fundamental question: How do we encode accountability back into these infrastructures and rebuild a foundation for civic life that is not merely an optimization of its own surveillance?

This is the work of one of our session organizers, Ricardo Barbosa.

Bosma, J. R., & van Doorn, N. (2024). Closing rent gaps through the professionalization of hosting. Space and Culture, 27(1).

Bosma, J. R. (2021). Platformed professionalization: Labor, assets, and earning a livelihood through Airbnb (Working Paper No. 49). Centre for Urban Studies, University of Amsterdam.

Guimarães, P. (2022). Tourism and Authenticity: Analyzing Retail Change in Lisbon City Center. Sustainability, 14(13), 8111.