Hello Interactors,

My wife and I recently started watching the mini-series 100 Foot Wave, which follows extreme surfer Garrett McNamara’s quest to ride the mythical 100-foot breaker. The show has put Nazaré, Portugal on the map — not just as a place, but as a symbol of human daring against forces far larger than ourselves.

At the same time, I’ve been listening to physicist-philosopher Sean Carroll’s recent “solo” podcast on the emergence of complexity, tracing how the universe began in simplicity and blossomed into stars, life, and consciousness. These two threads — towering waves and cosmic arcs — collided in my mind, stirring something that has been swelling in me for years: how to reconcile wonder at life’s improbable flourishing with despair at its accelerated unraveling on Earth.

Should despair be the only response? Or is it possible, like the surfers at Nazaré, to recognize the peril without surrendering to it — to ride, however briefly, the wave that could also destroy us?

THE COSMIC WAVE

Beneath the lighthouse bluff at Nazaré, Portugal opens a canyon 140 miles long and three miles deep — three times deeper than the Grand Canyon. Born of tectonic fractures and sculpted over millions of years, it is less a static feature than a force in its own right: a conduit that gathers the ocean’s momentum and hurls it shoreward. Swells that elsewhere would pass unnoticed are here magnified into walls of water, indifferent to whether they become playground or grave. Geography conspires — wind, current, and rock — but the canyon itself is an accomplice, a reminder that Earth is never merely stage but actor. For today’s surfers, this is possibility. For centuries of fishermen, it was peril. The waves have not changed, but the stance we take toward them has — and that, too, becomes part of the story the canyon tells.

So it is with complexity. Every wave begins simple, a long low swell born of distant winds, that crescendos into chaos at the shoreline. It swirls and curls into turbulent foam piqued in curious but dangerous beauty, only to dissolve back into undertow, bubbles, and silence. Our own cosmos follows the same rhythm, driven by the logic of entropy — the tendency of energy to spread, of order to give way to disorder.1 In the beginning, we know the universe was astonishingly simple and ordered: a hot, uniform plasma, almost featureless in its smoothness.

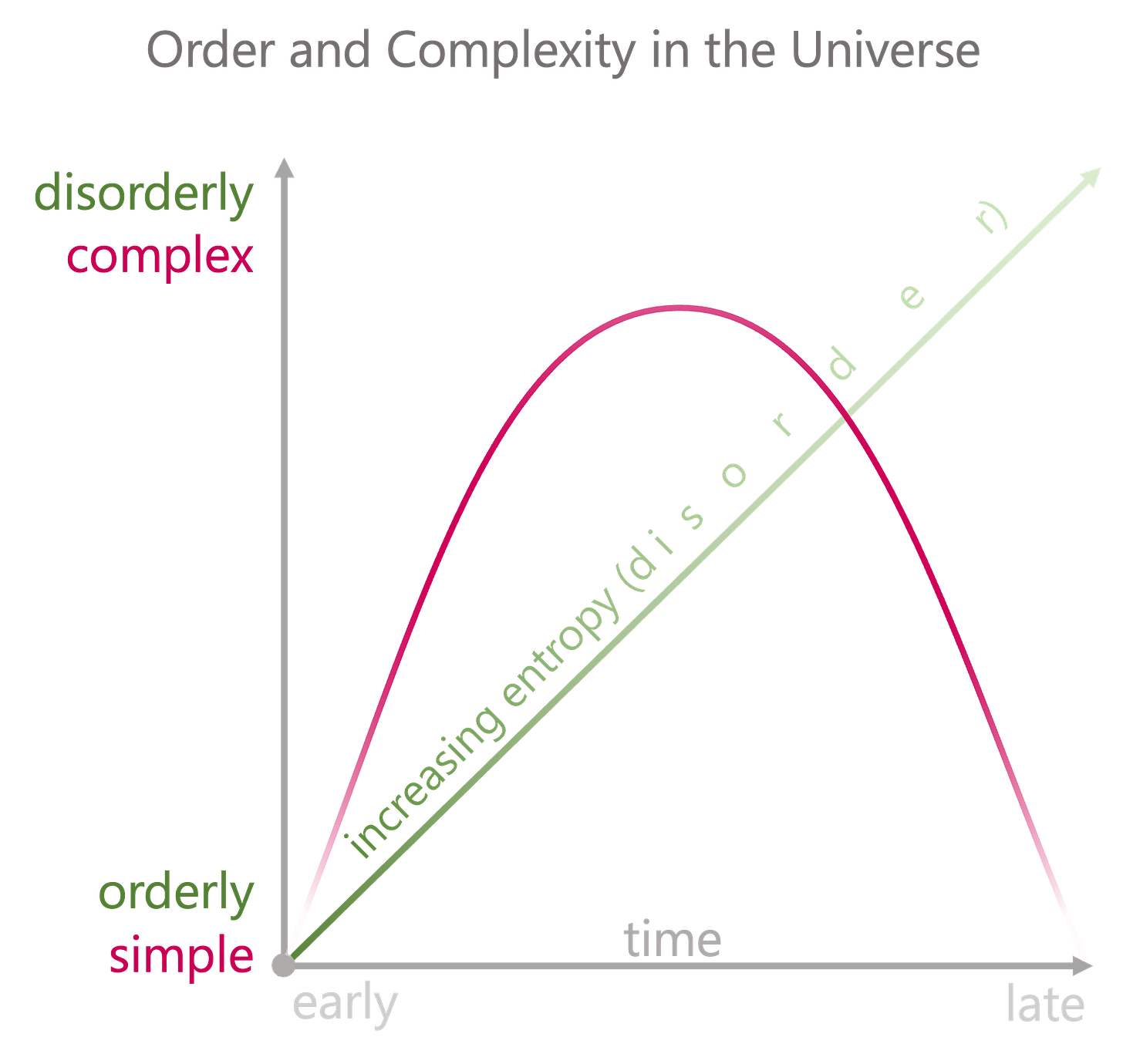

Imagine the origin of life sitting at origin of a graph. It exists orderly in low entropy and low complexity. But entropy is restless. As it advanced diagonally up and to the right disorder increases in a straight line. This opens space for complexity to emerge. Early on in the cosmos tiny quantum fluctuations stretched into patterns, atoms gathered into stars, stars fused new elements as galaxies spun, coalesced, and collided. Imagine this as the complexity line on our graph. It also grows with time but takes the shape of a parabolic wave climbing upward to a smooth crest as it increases in complexity. Meanwhile, entropy ticks steadily up and to the right as a straight arrow of time forever growing in disorder as our universe continues to increase in complexity.

We are now somewhere on this complexity curve. And this is the paradox of our middle epoch. Entropy never reverses course — disorder always increases — yet along that trajectory the complexity within we live crests, like a wave gathering its final height. For a sliver of cosmic time, the universe has been rich, complex, and with structure. On at least one world in the cosmos, life emerges and even creates complex organisms like us. But if entropy pushes inexorably forward, complexity will not hold indefinitely. Stars will exhaust their fuel, galaxies will drift into darkness, and matter itself may decay. This diagram reminds us that complexity rises only to fall again, tracing an arc back toward simplicity even as entropy continues its steady climb.

In this framing, the universe is not a march from order to chaos but a cycle of simple-to-complex-to-simple played out against entropy’s one-way slope. We live in a fleeting middle where complexity momentarily flourishes. Like the wave at Nazaré, born as a long low swell, steepening into a towering wall of water, then dissolving again into foam, undertow, and silence, our cosmos crests only once. The question is not whether entropy wins — it does — but how we dwell, and what we make of meaning, within the brief surge of complexity it permits.

It took a lot to get us to this point. This complex space that entropy has carved within cosmic time leaves room for novelty. Complexity flourishes locally even as disorder deepens globally. Out of this novel initial imbalance, life emerged — fragile metabolisms harvesting energy from their surroundings, weaving temporary order against the grain of entropy. From single-celled organisms to multicellular bodies, from photosynthesis to predation, biology layered new strategies of survival atop older ones. Evolution diversified life into forests and reefs, wings and fins, neural nets and circulatory systems. These proliferations multiplied niches where order could briefly hold, even as the larger cosmos drifted toward disorder.

Only much later did consciousness arise, one of evolution’s rarest experiments: a capacity not merely to metabolize energy but to reflect upon the arc of complexity itself. With awareness came memory, imagination, culture — tools for navigating the turbulence of entropy’s middle chapter. Entropy still holds the reins: the universe will drift back toward simplicity, whether into a thin uniform haze or some other quiet ending. Yet here, in the middle, entropy’s detour has produced extravagant complexity — including beings capable of gazing back at the wave that carries them and wondering what it means.

THE INDIFFERENT EARTH

This same gaze can also induce speculation. Like speculative realism. Emerging in the early 2000s as a reaction against a tendency to keep reality tethered to human thought and language, its central claim is stark: the world is indifferent to us. Planets orbit, tectonic plates shift, and waves break whether or not anyone is there to see them. From this view, complexity arises from imbalances in matter and energy, from unfinished processes that unfold far beyond human agency. The wave doesn’t care whether it is surfed or feared; it builds from wind, water, and terrain, cresting and dissolving with no meaning to maintain.

Animated globe of tectonic plates shifting across hundreds of millions of years, reminding us that Earth’s movements unfold indifferent to human presence or perception. Source: Reddit. And below is where we go from here:

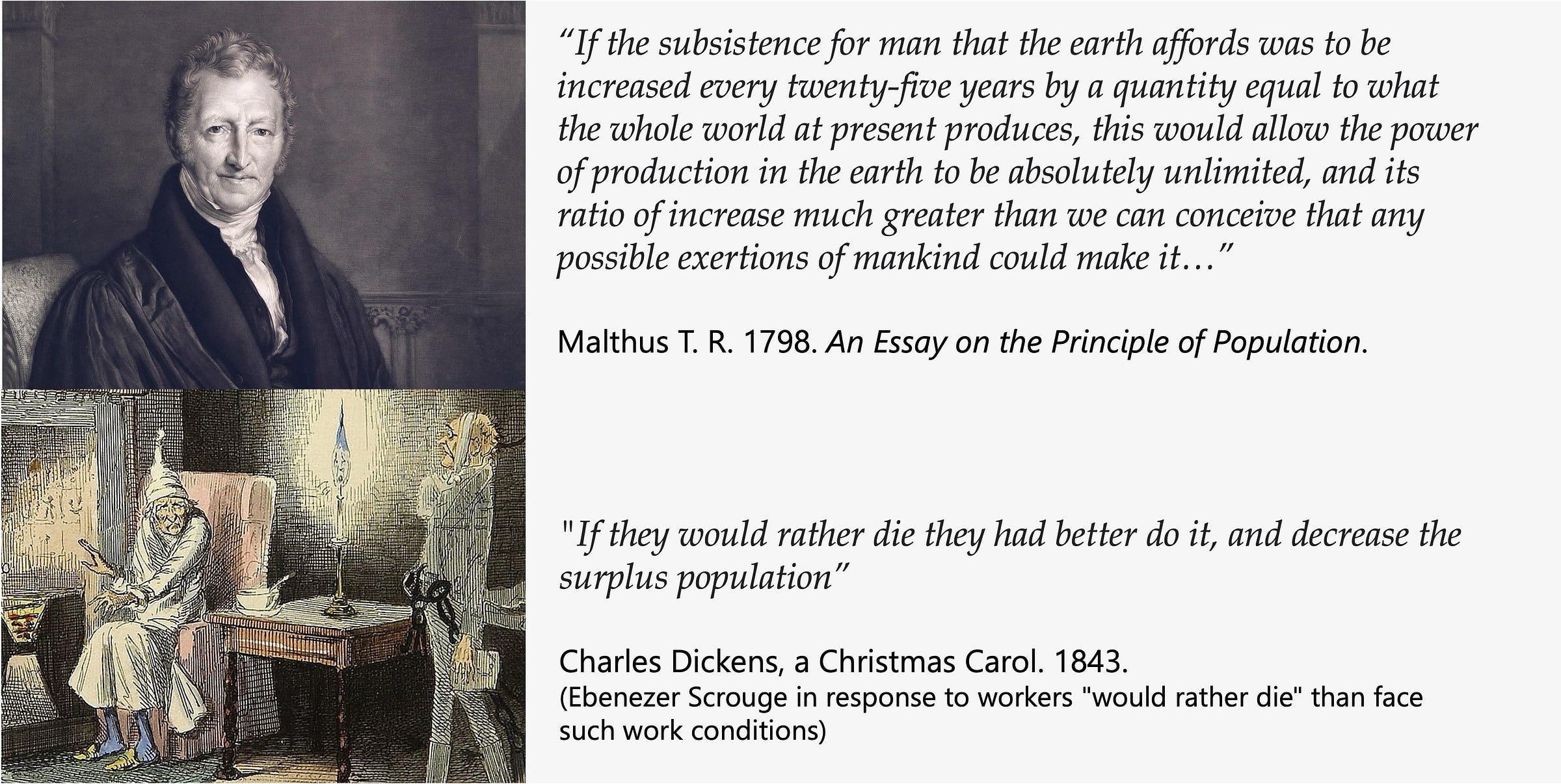

This speculation hits another conscious reality — optimism. Human optimism is as hard to contain as its constant refrain. Born of the Enlightenment but rebirthed amid the industrial expansion, world wars, and scientific breakthroughs of the early 1900s, modernist optimism leaned confidently on reason and science — a conviction that human ingenuity could transcend natural limits and bend uncertainty toward progress. Time and again, human ingenuity has found ways to stretch the boundaries of what seemed natural limits. Agricultural revolutions multiplied food production beyond what Malthus thought possible. Industrialization transformed energy regimes, substituting fossil carbon for dwindling forests. Urban innovations — from sanitation to electrification — allowed cities to grow far past the thresholds that once doomed them to collapse.2 Each leap suggested that collapse was not destiny but averted through cleverness.

This pattern sustains modernist faith: that humans can intervene wisely in the unfolding of complexity. Where speculative realism emphasizes the indifference of natural forces — entropy driving stars and systems toward disorder regardless of our designs — modernist thought wagers otherwise. It insists that ingenuity allows us not merely to endure the swell but to ride it, to carve temporary stability out of turbulence. In this view, the challenge of complexity is not simply to recognize its inevitabilities but to cultivate the foresight, restraint, and imagination that let human life persist in its fragile middle.

That is if humans “don’t do dumb things.” In other words, humans can and should preserve the conditions that let life and intelligence persist locally, even as the universal drift of entropy continues.3

Armed with the mathematical models that fuel both scientific confidence and human hubris, the world can appear elegant — even in its ugliness. Amidst entropy following a relentless trajectory we see scaling laws enfold organisms, cities, and civilizations alike. The planet itself is rendered as a singular complex system drifting through cosmic time. The physicist’s gaze simplifies this by design — reducing frictions, stripping away differences, until only lawlike arcs remain. As the polymath Heinz von Foerster once put it, “Hard sciences are successful because they deal with the soft problems; soft sciences are struggling because they deal with the hard problems.”4

Geography, by contrast, cannot ignore what falls through those cracks. The sweep of cosmology may remind us that complexity is not uniquely human — stars ignite, galaxies cluster, black holes churn — but such vistas stretch horizons so far that human lifetimes blur into insignificance. Civilizations, like waves, crest and crash in an instant against the span of cosmic time.

To move closer in, at a planetary scale, complexity narrows to the thin envelope where oceans, land, and atmosphere intertwine. It is within this fragile band that agriculture took root, cities rose, and civilizations flourished. Yet scientists, equipped with hard science, warn that this Holocene balance has already been breached.5 The “safe operating space” is no longer secure; the planetary is already in transition.

But even “the planetary” is too smooth a category. These upheavals are not shared evenly across the globe. They are bound to the ground — to places where histories sediment and lives unfold. From colonial dispossession to infrastructures of extraction, from economic logics that amplify inequality to political systems that harden vulnerability, complexity here is never neutral. It is situated, entangled with geographies of power and precarity.

What some describe as “geography envy” names this tension: physicists are drawn to Earth as a rich arena for testing universal models, yet in the process often flatten the contextual and uneven dynamics that geographers insist cannot be ignored.6 Geography refuses such reduction. It insists that the Earth is not merely a planetary system but a lived ground, fractured, uneven, and resistant to smooth incorporation into law-like arcs.

Speculative realism cuts deeper. It reminds us that both elegant arcs and messy ground are parts, never the whole. Reality is not exhausted by smooth models or contextual accounts; it exceeds them both. The planetary is not a canvas awaiting inscription, nor a kaleidoscope of situated and entangled stories. It is a force-field of matter and relation, where floods, famines, extinctions, and upheavals erupt whether or not we have the language to make sense of them.

Our minds, perhaps not yet evolved past binary thinking, want to declare one frame the winner: cosmic order or earthly mess. Modernism sought mastery through universal reason; postmodernism countered by unraveling every claim to stability. But metamodernism, a paradigm emerging in the 2010s, tries to move differently. It oscillates between these poles. It yearns for universal arcs while acknowledging the irreducible particularities of lived experience.

To see the “planetary” through this lens is to move between entropy’s inevitability and the instability of farmers, migrants, and city dwellers negotiating disrupted climates, markets, and states. Flows of capital expose some regions more than others, while systems of governance distribute or intensify that exposure. Human choices, bounded by perception and culture, compound these structural forces in ways behavioral geographers have long traced. All this unfolds across terrains and climates that set the boundaries of risk, while the distribution of plants, animals, and microbes reveals how even the nonhuman world is entangled in shifting geographies of survival.

DWELLING IN DUMBNESS

Complexity, then, cannot be abstracted into a question of whether it will continue. It will — cosmically, biologically, and geologically. The sharper question is how the continuities of our lived complexity register unevenly: whose livelihoods collapse, whose infrastructures crack, whose communities adapt or perish. Physics asks what the laws are; geography insists on whose lives are caught in them, whose ground is destabilized, and at what cost. Speculative realism pushes both disciplines to admit they never touch the whole: the real always exceeds our grasp, even as we are swept inside its turbulence.

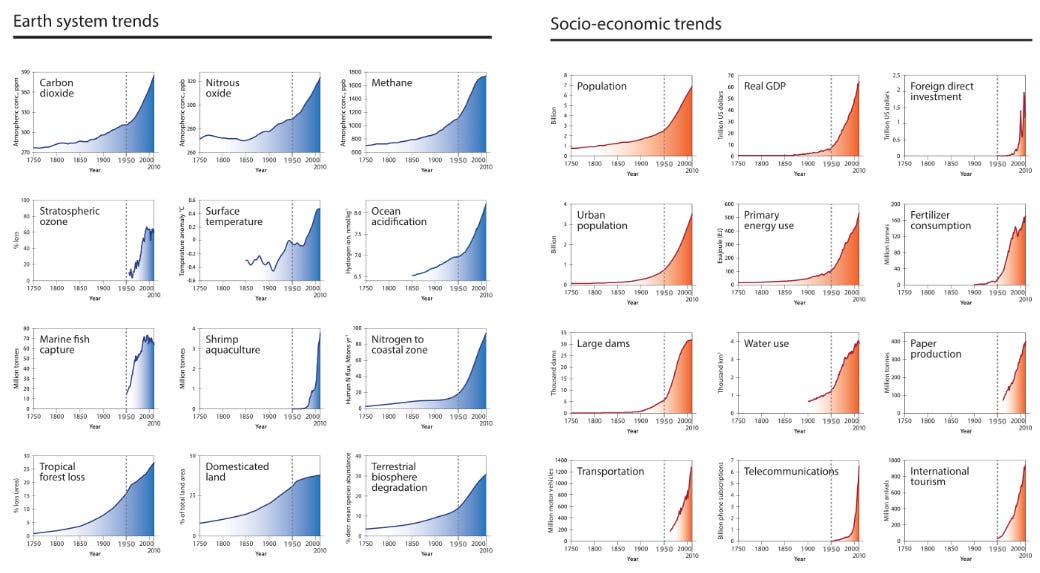

Even as we oscillate, it’s unsettling to accept that the Holocene’s narrow band of stability — the “safe operating space” — is already behind us.7 The so-called Great Acceleration shows that nearly every Earth system indicator — from carbon concentration to biodiversity loss, from ocean acidification to nitrogen cycles — has surged beyond Holocene bounds in the span of a single human lifetime. More specifically, the lifetime of my parents and/or me. These curves do not slope gently toward some distant tipping point; they spike upward, marking thresholds already crossed. Talk of future risk obscures the present tense: destabilization is not looming; we are living it.89 The rhythms of climate, soil, and water no longer conform to the stable backdrop against which civilizations emerged.

And yet, here again, we are re-inscribing the Earth as a backdrop through statistics. This triggers a tendency to mother our “Mother Earth”. We’ve taken her thermometer out, read the value, and have reasoned her temperature is life threatening. Humans can’t resist caring for ailing life. But branches of geophilosophy warns us to wake up.10 The planet is no patient and we’re no doctor. Fires, tectonics, and oceans act with or without us, indifferent to notions of care, justice, or intention found in advanced organisms.11 The Anthropocene is not solely the record of human decisions but the scene of inhuman forces that have long shaped life’s precarious conditions. Here speculative realism returns — reality unfolds beyond our categories, whether in cosmic entropy, metabolic scaling, or the volatile indifference of a sick and angry Mother Earth…or the violence of an impending wave.

I recognize this indifference but also recognize it does not absolve us. If anything, it should sharpen the ethical demand. To dwell within dumbness is to accept that the wave is already forming, but also to recognize that some bodies are naturally positioned closer to its break, some can’t surf, and others are made to suffer the buffering effects of a crashing wave. Metamodernism’s pendulum of tragic optimism may just offer a way through the wash. We need not kneel to the naïve belief in perpetual progress, nor retreat into ironic despair, but foster an ethic of persistence that takes seriously both human responsibility and inhuman indifference.

Like Nazaré’s canyon, the Anthropocene multiplies force from conditions already set in motion. Swells crest into walls that thrill the few who ride but have long drowned those with fewer choices. Complexity will continue, but justice requires asking not only how we dwell in turbulence, but whose lives are lifted, and whose are pulled under. The wager is no longer whether to master the wave. It is whether we can learn to inhabit it without denying the unequal costs it exacts.

Carroll, S. (2025, June 30). Solo complexity and the universe. Podcast. Preposterous Universe. Carroll, S. (n.d.). The physics of entropy and the origin of life. Video. Big Think.

West, G. (2017). Scale: The universal laws of growth, innovation, sustainability, and the pace of life in organisms, cities, economies, and companies. Penguin Press.

(1)

von Foerster, H. (2003). Understanding understanding: Essays on cybernetics and cognition. Springer-Verlag.

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., Biggs, R., … Sörlin, S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science.

O’Sullivan, D., & Manson, S. M. (2015). Do physicists have ‘geography envy’? And what can geographers learn from it? *Annals of the Association of American Geographers*. Advance online publication.

(5)

Verne, J., Marquardt, N., & Ouma, S. (2025). Planetary futures on life in critical times. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers.

West, G. (n.d.). Geoffrey West Johns Hopkins Natural Philosophy Forum the limits of human scale. YouTube.

(8)

Clark, N. (2011). Inhuman nature: Sociable life on a dynamic planet. SAGE Publications. Also, (8).