Hello Interactors,

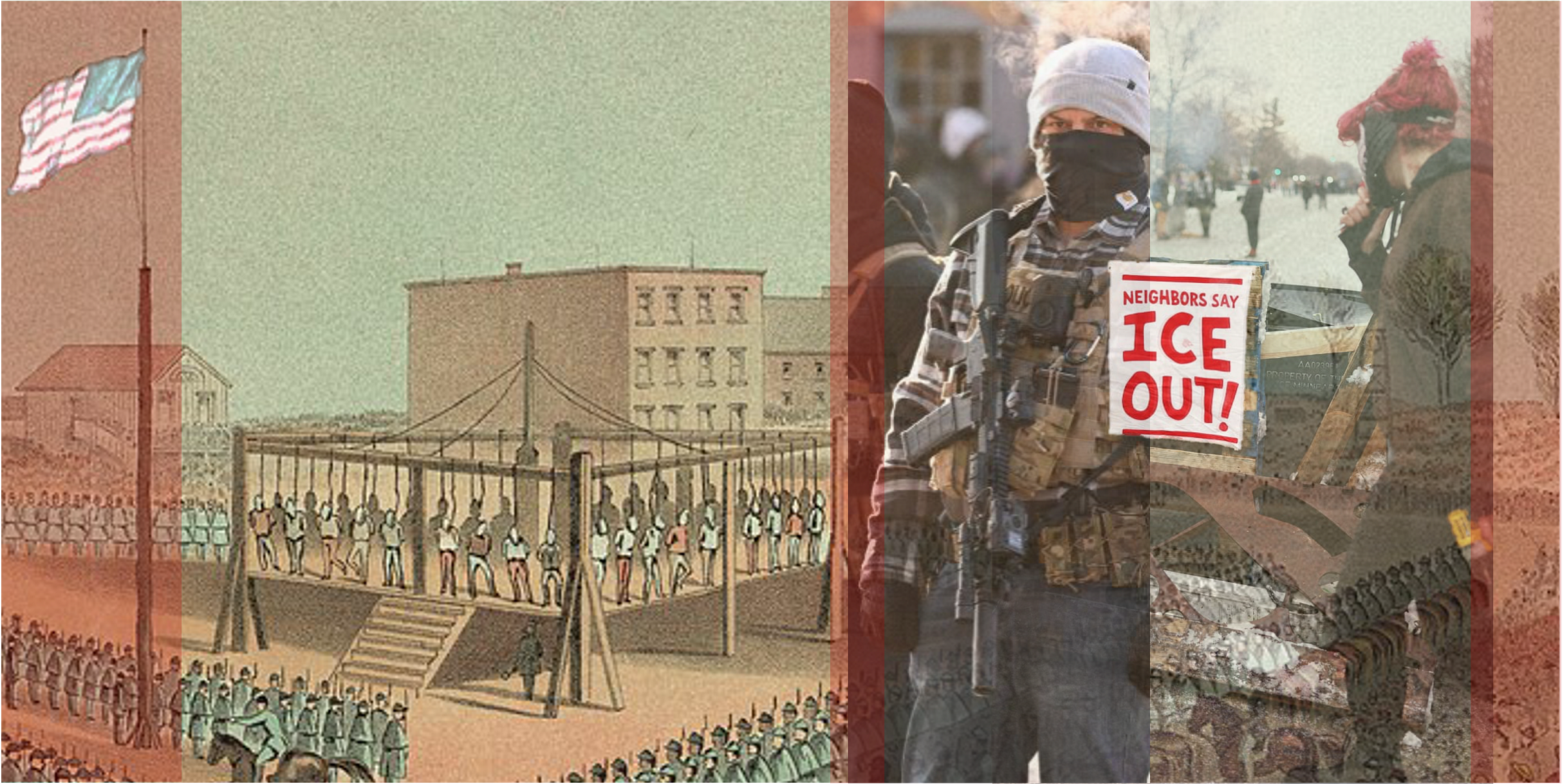

Minnesota has seen federal incursion and overreach before. And not just in 2020. These removal tests we’re witnessing are rooted in the premise of US ‘manifest destiny’ and how quickly the notion of ‘home’ can be made fungible by a violent state.

But likeminded bodies always resist being bullied.

SCAFFOLD, SOVEREIGNTY, AND SEIZURE

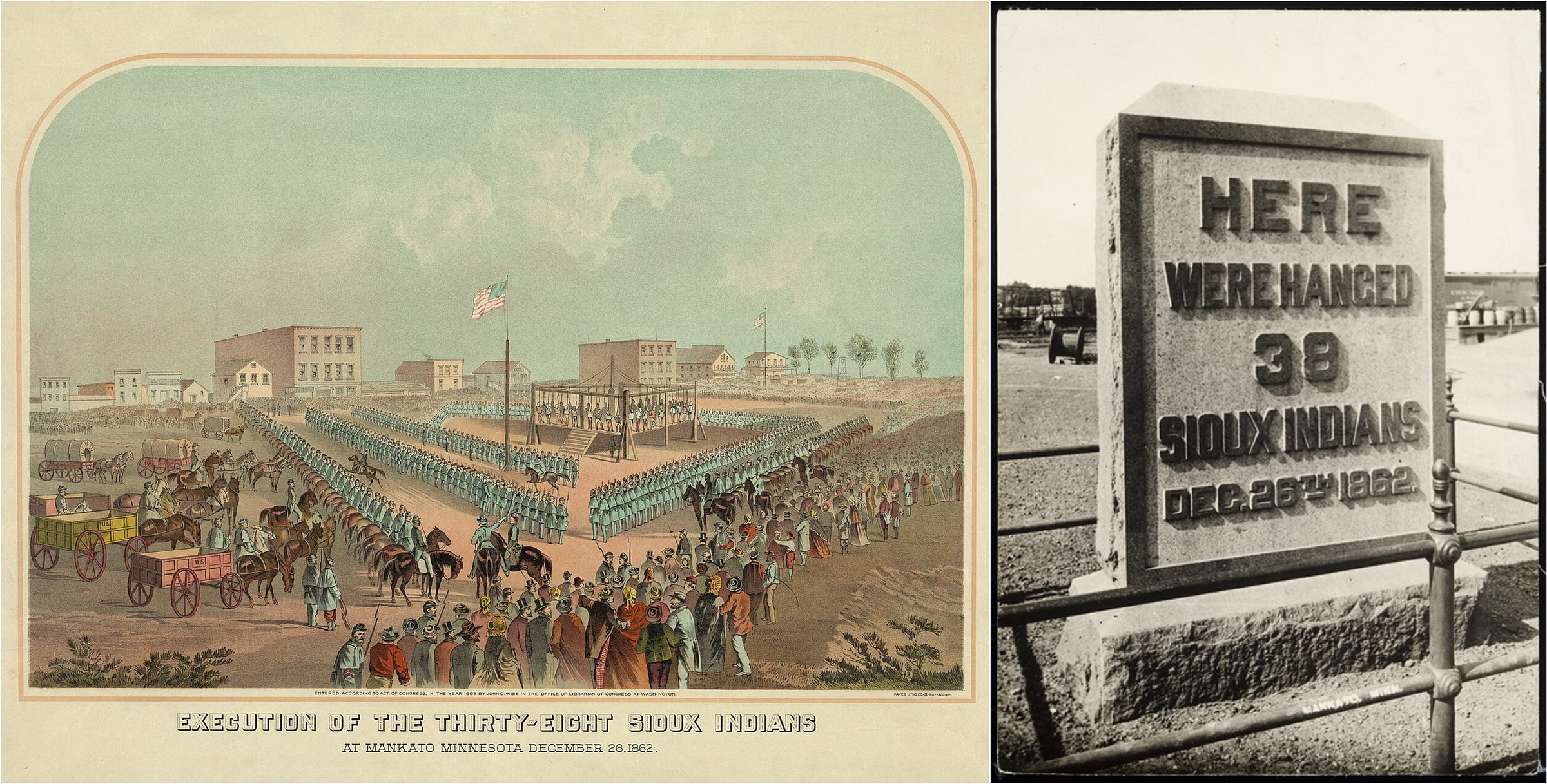

On December 26, 1862, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln authorized the hanging of 38 Dakota men in Mankato, Minnesota. The execution, staged as public theater, was not a solemn judicial act. A special scaffold was built, martial law was declared, and an estimated 4,000 spectators witnessed the largest mass execution in U.S. history.1

The spectacle mattered because it carried meaning beyond Mankato. The hanging marked the end of the six-week U.S.–Dakota War of 1862. This brutal conflict devastated the Minnesota River Valley and left deep trauma in Dakota communities. It also conveyed that the state could swiftly and effectively attempt control of contested land by violent force.

Mankato was the visible climax, but Fort Snelling was the quieter cruelty that continued. After the war, Dakota families — women, children, elders — were confined in harsh conditions near the fort during the winter of 1862–63. Disease and exposure killed between 130 and 300 Dakota people. Execution and exile worked together. One provided public power, the other attempted to ensure territorial outcomes.

Here’s what Dakota Chief Wabasha’s son-in-law, Hdainyanka, wrote to him shortly before his execution:

“You have deceived me. You told me that if we followed the advice of General Sibley, and gave ourselves up to the whites, all would be well; no innocent man would be injured. I have not killed, wounded or injured a white man, or any white persons. I have not participated in the plunder of their property; and yet to-day I am set apart for execution, and must die in a few days, while men who are guilty will remain in prison. My wife is your daughter, my children are your grandchildren. I leave them all in your care and under your protection. Do not let them suffer; and when my children are grown up, let them know that their father died because he followed the advice of his chief, and without having the blood of a white man to answer for to the Great Spirit.”2

This moral failing was part of a larger burgeoning political economy. In 1862, the Twin Cities were still emerging, with mills, river commerce, and infrastructure. Yet the region’s future as an urban, financial, and political center depended on converting Dakota and Ojibwe homelands into transferable property. The spring prior to the massacre, in May 1862, Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, handing out 160-acre chunks of stolen land labeled now as “public.” Colonizers and immigrants could occupy this land, and be defended by the US government, if they showed they could “improve” it through five years of occupation.

This act negated all Dakota treaties, seized 24 million acres of Minnesota lands, and mandated removal of what were now called Dakota “outlaws.” This converted communal Indigenous homelands into surveyed “public domain” eligible for homesteading, auctions, and rail grants, directly feeding wheat production for Minneapolis mills. Speculators and railroads exploited the act via proxy filings, reselling “cleared” parcels at profit to European immigrants.3

By 1870, non-Native population surged from 172,000 to over 439,000. The “clearing” of land was not metaphorical. It was the prerequisite for surveying, fencing, settlement, rail corridors, and the wider commodity circuits that would bind the Upper Midwest to national and global markets.

That is what Harvard historian Sven Beckert calls war capitalism. He argues that global capitalism’s ascent was not a clean evolution toward free exchange. It relied on coercion, conquest, and violence. As his book on the history of Capitalism lays out, state funded war capitalism fundamentally relied on slavery, the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, imperial expansion, armed commerce, and the imposition of sovereignty over both people and territory.4

In this framing, the Dakota and Ojibwe were obstacles to industrialization and commodification. The frontier needed to be safe for settlement and investment of Germans, Irish, and Scandinavians, as well as railroads and industry. This included these two flour mills, the world’s largest by 1880: General Mills and Pillsbury.

The gallows in Mankato were the blunt instrument that made the state-capital alliance credible. The point was not only to punish alleged crimes, but to demonstrate a capacity and will to kill. The American state needed to show it could override Indigenous sovereignty and reorder space. The subsequent removals and confinement at Fort Snelling completed the transformation. “Home” was recoded from relationship into asset. This land was no longer lived geography but extractable territory, from stewarding real soil to the selling of real estate.

TOPHOPHILIA, TIES, AND TENSIONS

War capitalism is not merely to punish resistance, but to convert a lived place into a fungible asset. But violence plays a deeper role than just legal rearrangement. It has to break this constant of human life: our attachment to place.

Behavioral geographer Yi-Fu Tuan borrowed the term topophilia to describe this attachment — the “affective bond between people and place or setting.”5 The phrase can sound soft and sentimental but it can also cause friction in projects of political economy.6

The state may be able to abolish or rewrite a treaty, redraw a border, rename a river, and issue new deeds, but it still confronts bodies that have been oriented by firm ground. It’s on these grounds that paths are walked, food gathered, relatives buried, stories anchored to landmarks, and seasonal rhythms internalized as a habit of life. The obstacle is embedded and embodied in the physiology, including cognitive, and grounds to location.

Modern neuroscience gives a concrete account of how place becomes part of a person. The hippocampus plays a central role in spatial memory and navigation, and research on place cells shows that hippocampal neurons fire in relation to specific locations in an environment.7 Familiar surroundings are not only around us they are within us. The brain builds spatial scaffolding that links location to memory, routine, prediction, and emotional regulation.

When cognition is tied to the specificity of place, it becomes hard for a parcel to be made equivalent to another. Commodification demands interchangeability. A home cannot easily be made equivalent to another home when it’s part of the nervous system — not quickly, not cleanly, and often not at all. When the state-capital alliance imagines territory as a grid of extractable value, it is implicitly trying to override how humans experience territory.

That is why “simple” displacement so often produces disproportionate harm. Psychiatrist Mindy Fullilove coined the term root shock to describe the traumatic stress that follows the destruction of one’s “emotional ecosystem.”8 Root shock is not only grief or nostalgia. It is a stress response to the sudden loss of the social and spatial cues that stabilize daily life. The shredding of a mesh of relationships, routines, and meanings embedded in a neighborhood or homeland.

The root shock of the state violence of 1862 was not just incidental to the project of transformation. It was structurally necessary. If topophilia is a biological and psychological anchor, then a purely legal or economic strategy (bureaucratic coercion) will often be insufficient because the anchor of topophilia holds. To clear land at speed and scale, the state reaches for tools that can sever attachment abruptly. Public executions, mass incarceration, forced marches, and exile doesn’t just relocate people. They’re violent attempts to scramble the conditions under which people can remain attached at all. It transforms topophilia into vulnerability.

Work on social exclusion and “social pain” helps explain why. In a widely cited fMRI study, Naomi Eisenberger and colleagues found increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex during experiences of exclusion. This parallels patterns seen in physical pain studies where distress is tracked with painful activities.9 The point is not that social threat is “just like” physical injury, but that the brain treats social severing as a serious alarm condition. It’s something that demands attention, vigilance, and behavioral change to overcome.

ROOTS, RESISTANCE, AND REPAIR

Topophilia doesn’t end with the so-called frontier or attempts at ‘removing’ its inhabitants. It reappears wherever people form durable bonds. That includes the streets and schools, churches and parks, language, kin, and the local economies and cultures war capitalism eventually built. The Dakota and Ojibwe were never “removed” in any final sense. Many live and organize in and around the Twin Cities today.

In South Minneapolis, the Indigenous Protector Movement, a biproduct of the American Indian Movement, works out of the American Indian Cultural Corridor along Franklin Avenue — an immediate target for ICE. The protectors made their presence known as a form of ongoing place-based care and defense.

It is a living archive of tactics for defending attachment under pressure through direct action, community building, patrols, and the mundane discipline of showing up. What it offers is not merely a critique of state violence, but vigilance without spectacle, care without permission, and solidarity as a daily habit rather than a momentary sentiment.

Other areas of Minneapolis show how when federal enforcement turns public space into a zone of uncertainty, topophilic neighbors often respond by adopting exactly those same “weapons” of persistence — care, documentation, rapid communication, mutual aid — that have long characterized Indigenous resistance and slavery abolitionist networks.

Standing Rock, where the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and allies gathered in 2016 to oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline, demonstrated how quickly infrastructure can scale when a place becomes a shared object of defense.

The #NoDAPL movement assembled a broad coalition of Indigenous nations and allies, over 200 tribes, alongside legal support, medical care, and communications systems designed to withstand state patience.10

The 2020 George Floyd uprising in Minneapolis also revealed how love of place can become a platform for organized care rather than retreat. Alongside protest, residents built mutual-aid channels, street-medic networks, food distribution, and neighborhood defense efforts that treated the city as an emotional ecosystem worth repairing. What looked to outsiders like spontaneous eruption was, on the ground, a rapid layering of roles that included medics, legal observers, supply runners, translators, and de-escalators. This ecology of participation made it possible for large numbers of people to act without centralized command.

Social psychology helps explain why these movements generate allies rather than only sympathizers. One key concept is collective efficacy — the combination of social cohesion and a shared willingness to intervene for the common good.11 It blossoms when people repeatedly see each other act, learn local norms of mutual obligation, and build trust that intervention will be supported rather than punished. All rooted in topophilia.

Place attachment can bridge boundaries that would otherwise keep people separate. Work in community psychology and planning shows that place attachment and meaning can support participation and collective engagement, especially when development or coercion threatens everyday life.12 In other words, topophilia is not just private feeling. When it’s under threat it can become public motive and an engine for coalition.

The coalition in Minneapolis is being characterized by the federal government as terrorists. This borrows from a long history of resistance to violence because war capitalism has never been only domestic. The United States and its allies refined coercive governance overseas through night raids and “capture-or-kill” operations in Afghanistan, midnight house raids in Iraq, and broader militarized campaigns that treat homes as “searchable terrain” and communities as “intelligence environments.”

Many of the officials, contractors, and voters who authorized or normalized these methods rarely imagined the same atmosphere of violent seizure in their neighborhood. As unimaginable as it may be watching unmarked vehicles, sudden detentions, and public uncertainty coming to American streets — used against the very citizens and taxpayers who fund such operations — it’s not to those victims overseas in places like Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, or even inner city America.

That return is what the poet and politician Aimé Césaire called the “imperial boomerang” effect, the idea that techniques tolerated in peripheral countries can come home to roost. In the U.S., the boomerang has long “landed” first on people of color. It emerges through surveillance and disruption campaigns like the two decades of the covert and illegal COINTELPRO program where the FBI targeted counterculture groups of the so-called New Left.

Or the “Palmer Raids” of 1919 and 1920 targeting largely Italian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants and their left-leaning politics. These led to riots in 30 US cities and culminated in the bombing of the home of A. Mitchell Palmer, the US attorney general. These programs all reflect the notion that war can come home — just look at the increased militarizing of policing complete with SWAT tactics.

And the same history that produced the scaffold of war capitalism of the past also produced reservoirs of resistance we see here and now. When neighbors anywhere respond to incursions not only with fear but with organized vigilance and material support, they are adapting older strategies of care found in Indigenous, abolitionist, and other movement-based defenses of people and places against infiltration, intimidation, and attempted violent removal.

We can see how war capitalism endures. Mankato’s 1862 gallows aimed to clear Dakota homelands of their people for homesteading, rails, and mills. Meanwhile, today’s Operation Metro Surge includes thousands of federal agents raiding Minneapolis homes and streets, attempting to sever immigrant attachments to allegedly enforce labor control and national security. These militarized spectacles of warrantless entries, tear gas, and shootings echo what Beckert has uncovered. They treat people and place as obstacles to commodification rather than roots of stewardship.

Yet topophilia also persists. These cross cultural rapid-response networks are not new to these lands, even though the US government tried to erase them centuries ago. The inspiring actions we see in Minneapolis reflect the values of compassion, positiveness, and respect for all relatives with neighborly solidarity that the first occupants of that land embraced. They’re now woven with their allied 21st century neighbors in common and shared resistance. As best expressed here by Indigenous studies and political ecology scholar Melanie Yazzie. (and the longer version here)

Minneapolis, like those acts of resistance in the nearby Dakotas, enacts and rehearses an alternative form of civil governance that centers mutual obligation over coercion and extraction. It shows how cities can survive the strain and stay alive — not through fear and gain, but through care that grounds and sustains.

Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An indigenous peoples’ history of the United States (ReVisioning American history). Beacon Press.

Minnesota Historical Society. The trials & hanging. U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

Ibid

Beckert, S. (2025). Capitalism: A global history. Penguin Press.

Hoelscher, S. (2006). Topophilia. In Encyclopedia of human geography. SAGE Publications, Inc.

It should be noted that topophilia can also fuel racism, nationalism, and NIMBYism by twisting the love of place into exclusive possessiveness that rejects outsiders as threats to one's cherished homeland or neighborhood.

Best, P. J., White, A. M., & Minai, A. A. (2001). Spatial processing in the brain: The activity of hippocampal place cells. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24.

Fullilove, M. T. (2016). Root shock: How tearing up city neighborhoods hurts America, and what we can do about it (2nd ed.). New Village Press.

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science

American Civil Liberties Union website. Stand with Standing Rock.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science.

Manzo, L. C., & Perkins, D. D. (2006). Finding common ground: The importance of place attachment to community participation and planning. Journal of Planning Literature.