Hello Interactors,

It’s winter. So, as the sun tilts toward the sun (up north) my writing tilts toward the brain. It’s when I put on my behavioral geography glasses and try to see the world as a set of loops between bodies and places, perception and movement, constraint and choice. It’s hard to do that right now without running into AI. And one thing that keeps nagging at me is how AI is usually described as this super-brain perched in the cloud, or in a machine nearby, thinking on our behalf.

That framing inherits an old habit of mind. Since Descartes, we’ve been tempted by the idea that the “real” mind sits apart from the messy body, steering it from some inner control room. Computer metaphors reinforced the same split by calling the CPU the “brain” of the machine. And now we’re extending the metaphor again with AI as the brain of the internet, hovering overhead, crunching data, issuing guidance. An intelligence box directing action at a distance is a tidy picture but it risks making us miss what’s actually doing the work.

Let’s dig into how the brain leverages the loops of people, places, and interfaces we all move through to extend it’s richness and reach.

GRADIENTS GUIDE WHILE BODIES BALANCE

Have you ever hiked or skied in snow or fog and seen the middle distance just in front of you disappear? It takes the world you thought you knew, like ridge lines, tree lines, and the comforting predictable geometry of “just ahead” and reduces it to panic stricken near-field fragments. I’ve sensed once familiar ski runs become suddenly unfamiliar not because it changed, but because it was no longer accessible to my brain.

In these moments, we’re all forced to reckon, recalibrate, and (usually) slow down as our senses sharpen. We take note of the slope under our feet and the way the ground shifts. We listen for clues our eyes can’t see and notice which direction the wind is blowing, how the light is changing, and how our own heartbeat and breath changes with each calculated risk. We know where we are, but the picture is fuzzy. Our memory only gets us so far. Everything around us becomes this multi-faceted relationship between our body making sense of it all while our brain updates its status moment by moment. The last thing a brain wants is to have its co-dependent limbs fail and risk falling.

That experience demonstrates how the world is coupled with us. In world-involving coupling a living system survives through ongoing coordination with the affordances and constraints of its surroundings. In behavioral geography this frames spatial behavior as dynamic, reciprocal coordination between individuals and their environments, rather than just isolated internal cognition.

Places actively shape decisions through the physics of the world and all its constraints. Actions, in turn, then reshape those surroundings in ongoing loops. This approach to cognition shifts focus from isolated mental maps to lived, constitutive engagements. It treats the world as a partner in our own competence.

Before brains, gradients existed. Living systems navigated heat, cold, salt, sugar, thirst, dark, and light to persist. The first cognitive problems were biophysical. Surviving in a world that constantly disrupted viability relied on basic mechanisms like membrane flows, chemical reactions, and feedback. These primordial loops coupled an organism to a given environment directly. There were not yet any neural intermediaries. These were protozoa drifting toward nutrients or recoiling from toxins. It is in this raw attunement that world-involving coupling emerges.

In 1932, physiologist Walter Cannon coined the term “homeostasis” to describe the body’s active pursuit of stability amidst environmental pressures. Living systems, whether single-celled or more complex, maintain survival variables within narrow bands. Cells detect changes in these variables, which affect molecular states. Temperature, acidity, pressure, osmosis, and metabolic concentrations all influence reaction rates. Feedback loops alter cell-environment interactions through heat transfer, ion flux, water movement, and gas exchange, ultimately restoring the system to a viable band. Organisms are not passive vessels but actively engage with these detection loops, triggering adjustments like a wilting plant drawing water. Sensing and action are fused operations for persistence.

About 600 million years ago, cells in an ancient sea sensed electrical fields or chemical plumes on microbial mats. These pioneering cells formed diffuse nerve nets, evolving into jellyfish and anemones. Simple meshes firing to contract thin membranes in bell-shaped forms, they lacked a brain but coordinated propulsive pulses to keep the organism in bounds or sting prey. Within 10s of millions of years, bilateral animals evolved. Flatworms like planaria emerged with nerve cords laddered along their undersides, thickening toward their tips. These proto-brains sped signal spread across their elongated forms.

As vertebrates appear, control becomes more layered. Circuits in the brainstem evolve to coordinate breathing, heart rate, posture, and basic orienting reflexes. The cerebellum emerges to sharpen timing and coordination. Competing actions, drives, and habits become sorted with the help of the basal ganglia. With mammals — and especially primates — the cortex expands. Perception and action become more flexible across situational contexts and with it comes longer-horizon learning, social inference, and planning.

But at every milestone, bodies are still constrained and governed by gradients and fields related to gravity, friction, heat, oxygen, hydration, predators, prey, and terrain. The cortex sits on top of these older loops, stretching them in time and recombining them in new ways. Even the most “abstract” human cognition still rides on the same foundation of reflexes and sensorimotor sampling. This is what keeps an organism in operable biochemical ranges while it propels itself through an environment that perpetually pushes and pulls.

BOXED BRAINS BEGET BIG BELIEFS

The field of physiology deepened this bio-chemical inquiry through the early 20th century. Physiologist and neurologist Ivan Pavlov revealed how sensory cues could chain to responses through neural rerouting creating conditioned ‘Pavlovian’ reflexes. Neurophysiologist Charles Sherrington coined the term “synapse” as he dissected and described them as switches in these loops coupled to the world. Through this inquiry, the autonomic nervous system emerged as a kind of homeostatic controller. Sympathetic surges in the system were found to create fight or flight reactions as our parasympathetic system kicks in to dial us back. This can be seen as a more complex version of the same push-pull of Cannon’s original homeostasis.

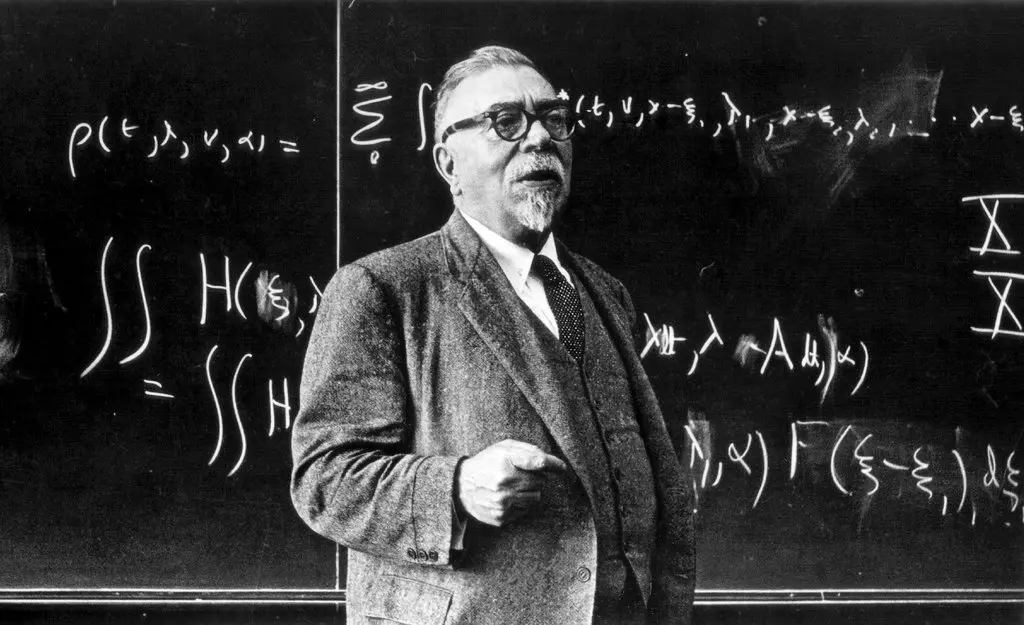

By the mid-20th century, mathematician and philosopher Norbert Wiener, working closely with physiologists and engineers, compared the nervous system to a servomechanism — a self-correcting governor found in engines. He coined the term cybernetics in his 1948 book Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine where he treated animals and machines as systems that regulate themselves through feedback.1

He and his collaborators argued this was a form of “purposeful behavior” or goal-directed action — a kind of negative feedback loop that reduces the difference between a current state and a target state.2 These ideas hardened in engineering fields during wartime as they were used in weapon systems for prediction and control of trajectories by compensating for delay and uncertainty. Cybernetics helped make the physiological regulation of Cannon’s biological homeostasis structurally analogous to engineering.

This mechanical metaphor sparked a long-standing debate, dating back to Descartes’ 17th-century mind-body split. Dualism posited an immaterial mind as a rule-following pilot controlling mechanical flesh. Alan Turing’s 1936 paper had already formalized this possibility, presenting a “machine” capable of computing any algorithm.3

Two decades later, the Dartmouth summer workshop coined “artificial intelligence” and encouraged the idea of engineering minds as programs.4 Around the same time, Herbert Simon and Allen Newell built early “logic theorist” programs that proved theorems, making intelligence seem like a boxed process involving symbols and reasoning.5

That lineage hasn’t disappeared. This is largely the default engineering posture of AI. Even when the machinery shifts from hand-coded rules to learned statistical patterns, we still talk as if intelligence lives inside a system. AI models claim to “form representations,” “build a world model,” “store knowledge,” “plan,” and “reason.” Contemporary training methods reward this language because they really do produce rich internal states that can be probed, steered, and reused across tasks.

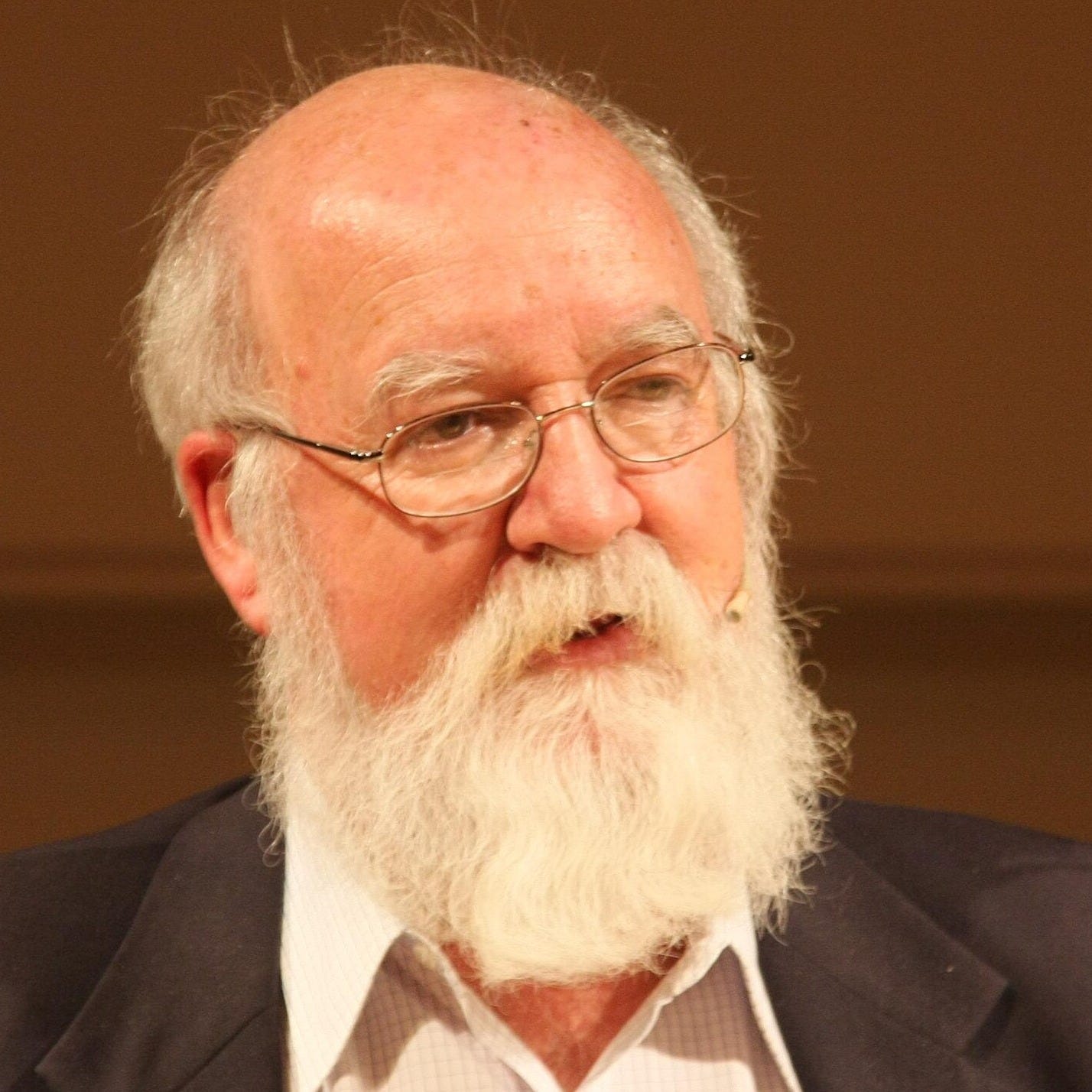

Less discussed is the metaphysical shift from “the system has internal structure supporting performance” to “the system contains an inner arena where meaning emerges and is inspected before action.” Daniel Dennett, a philosopher who dismantled this intuition in theories of mind and consciousness, called this picture the “Cartesian theater.”6

He noticed that scientific explanations often subtly reintroduce the central place where “it all comes together” for an internal witness. Dennett believes this inner stage is a comforting fiction derived from Descartes’ split between observer and world. Brain imaging reveals coordinated network activity, but not a literal inner ‘screen’ presenting a unified world-model. Many neuroscientists describe cognition as emerging from distributed, parallel, and recurrent processes, sometimes with large-scale integration.7 Dennett’s point is not that internal processing is unreal, but that our language tempts us toward a surreal Cartesian picture in a central place we can’t empirically reveal.

RESAMPLE, RESTABILIZE, AND RESHAPE

Neuroscience reveals that perception differs from a camera feeding a private theater. Our eyes rapidly sample information based on our actions, and the brain stabilizes perception during movement. Much visual processing is organized in the service of action, with partially distinct but interacting pathways supporting perceptual report and real-time visuomotor control.8 This suggests that the brain resembles a system for maintaining a relationship with the world through continuous sampling, correction, and skilled engagement, rather than a world-reconstruction engine.

James J. Gibson, the founder of ecological psychology, arrived at a similar conclusion earlier from behavioral and perceptual evidence. He argues that the world provides lawful patterns, regularities constrained by physics and geometry, that guide behavior because they remain stable across changing viewpoints. These patterns are not complete. Organisms make them available by moving, shifting gaze, turning the head, walking, or touching. Perception is an active process of sampling the world.

If perception is about staying attuned to lawful structures in the environment, the evolutionary consequence is organisms don’t just read the world, they also write it. As organisms became more complex and mobile, they gained the power to reshape the very patterns they depend on. They start cutting paths (pathways worn into grass, game trails beaten into forests), building shelters (bird nests, termite mounds, human dwellings), altering flows of water and heat (beaver dams, termite mounds), and laying chemical trails (ants depositing pheromones).

Evolutionary biologists call this niche construction. Organisms modify their environments, which then feed back into selection pressures and development, creating a dynamic cycle where the environment becomes a product of life and a force that shapes it further.9 As the world guides behavior, behavior reshapes the world, and the remade world trains bodies and brains into new skills and expectations. Over time, these modifications become external organs of coordination, storing information, reducing uncertainty, and channeling action.

A worn trail is navigational memory made durable, a nest or mound is a climate-control device that stabilizes temperature and airflow, and a pheromone path is a distributed signal that recruits other ants into collective action and direction. Complexity scientist David Krakauer calls this broader idea of “mind outsourced into engineered matter” exbodiment — where artifacts actively constrain and channel cogntion.10 In this view, cognitive work is no longer confined to nervous tissue but accomplished through bodies working with worlds they’ve built.

Humans take this to an extreme. Clothing and shelter externalize thermoregulation, fire externalizes digestion and protection, tools externalize force and precision, drugs alter chemistry, writing and calendars externalize memory and timing, and institutions externalize norms and coordination. Much of what we call “human intelligence” is not only in our brains but also distributed across artifacts and practices that have accumulated over generations.

Cognitive anthropologist Edwin Hutchins made the point vivid by studying navigation. On a ship, “knowing where you are” is not privately derived nor sealed in a captain’s skull. It is a collective achievement through a system of charts, maps, instruments, procedures, language, coordinated roles — an entire ecology of cognition comprised of tools and social organization.11 Here geography and cognition merge. Orientation is not just mental but enacted in relation to representations that are anchored and socially maintained in our material reality.

When I was at Microsoft, I followed the work of sociologist Lucy Suchman who studied human-machine interaction. She arrived at a similar conclusion criticizing the fantasy that action is simply “execution of an internal plan.” Real action, she argues, is situated. It’s responsive to unfolding circumstances — often improvisational — and is shaped by context in ways that cannot be fully specified in advance.12 In other words, if we look for intelligence as a prewritten script inside the head, we will miss how intelligence is often produced when enacted in a world that refuses to hold still.

Large language models, at first glance, seem to embody the “internal plan” fantasy. They’re sealed systems containing competence in weights and parameters, ready for queries. However, they’re closer to Suchman’s warning. Trained on vast archives of human writing, LLMs learn statistical regularities in vast continuations of text. When used, they produce a new continuation conditioned on prompts and context.13 Prompts aren’t mere inputs. They’re situated actions in human-computer interactions. They set frames, narrow affordances, cue roles, establish constraints, and often iterate in a back-and-forth that resembles Suchman’s improvisation with a powerful partner who is also techy and textual.

Philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers, in their extended mind thesis, claim under certain conditions, external tools can become constitutive parts of cognition when they are reliably integrated into the organism’s routines.14 As we’ve learned, the boundary of cognition is not always the boundary of skin or skull, it’s the boundary of a stable loop.

When the fog rolls in and visibility gets low, the boundary of this loop becomes quickly apparent. “The mind’s eye” is not that helpful…practically or metaphorically. If anything, the brain wants nothing more than for the body to widen contact with the world. It slows us down, sharpens listening, and increases tactile attention. It calculates different gradient thresholds to measure risk…it might even glance at an external sensing device that is prompting some intervention or improvisation! We are not watching a movie in our head to get through the fog. We are trying to stay oriented in a world that refuses to be fully represented.

This is the reframing of intelligence — artificial and otherwise — I wish for. I’d like to see more talk of intelligence being less a coveted individualistic thing hidden inside us and more an achievement of coordinated biophysical, social, infrastructural loops across time. When we mistake a metaphor (“there’s a theater in there”) for an ontology (“that’s where cognition lives”), we get misled about minds and we get misled about AI. The alternative is not anti-technology. It’s conceptual hygiene. Let’s start asking where cognition actually happens, what it is made of, and how places — natural and built — participate in making it possible. You know, Interplace — the interaction of people and place.

Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics: Or control and communication in the animal and the machine. MIT Press.

Rosenblueth, A., Wiener, N., & Bigelow, J. (1943). Behavior, purpose and teleology. Philosophy of Science.

Turing, A. M. (1936). On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society.

McCarthy, J., Minsky, M., Rochester, N., & Shannon, C. (1955/1956). A proposal for the Dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1956). The logic theory machine—A complex information processing system. IRE Transactions on Information Theory.

Dennett, D. C. (1991). Consciousness explained. Little, Brown and Company.

Mashour, G. A., Roelfsema, P., Changeux, J.-P., & Dehaene, S. (2020). Conscious processing and the global neuronal workspace hypothesis. Neuron.

Milner, A. D. (2017). How do the two visual streams interact with each other? Experimental Brain Research

Odling-Smee, F. J., Laland, K. N., & Feldman, M. W. (2003). Niche construction: The neglected process in evolution. Princeton University Press.

Krakauer, D. C. (2024). Exbodiment: The mind made matter. arXiv.

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. MIT Press.

Suchman, L. A. (1987). Plans and situated actions: The problem of human–machine communication. Cambridge University Press.

Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., … Amodei, D. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis