Hello Interactors,

Spain’s high-speed trains feels like a totally different trajectory of modernity. America prides itself on being the tech innovator, but nowhere can we blast 180 MPH between city centers with seamless transfers to metros and buses…and no TSA drudgery.

But look closer and the familiar comes into view — rising car ownership, rush-hour congestion (except in Valencia!), and growth patterns that echo America.

I wanted to follow these parallel tracks back to the nineteenth-century U.S. rail boom and forward to Spain’s high-spe ed era. Turns out it’s not just about who gets faster rail or faster freeways, but what kind of growth they lock in once they arrive.

TRAINS, CITIES, AND CONTRADICTIONS

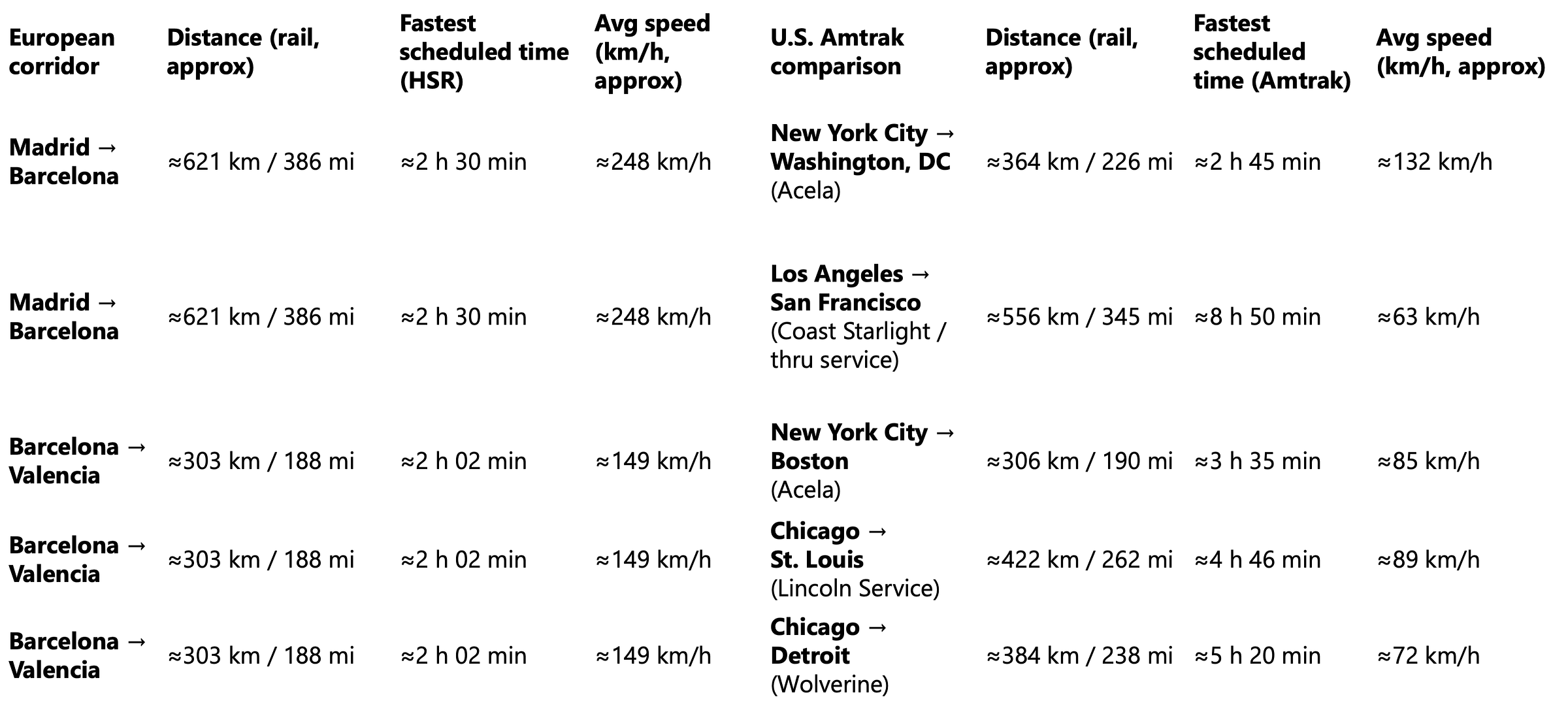

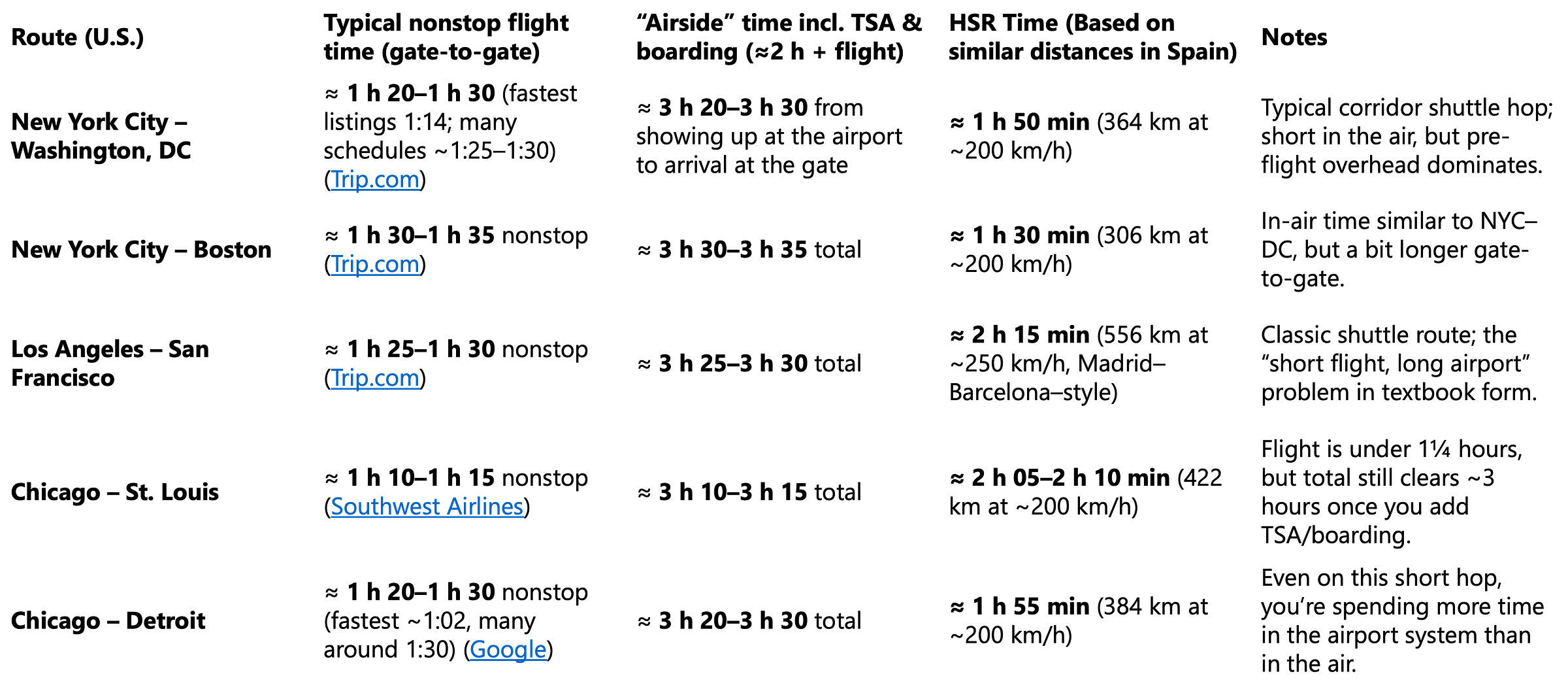

My wife and I took high-speed rail (HSR) on our recent trip to Spain. My first thought was, “Why can’t we have nice things?”

They’re everywhere.

Madrid to Barcelona in two and a half hours. Barcelona to Valencia, Valencia back to Madrid. Later, Porto to Lisbon. Even Portugal is in on it. We glided out of city-center stations, slipped past housing blocks and industrial belts, then settled into the familiar grain of Mediterranean countryside at 300 kilometers an hour. The Wi-Fi (mostly) worked. The seats were comfortable. No annoying TSA.

Where HSR did not exist or didn’t quite fit our schedule, we filled gaps with EasyJet flights. We did rent a car to seek the 100-foot waves at Nazaré, Portugal, only to be punished by the crawl of Porto’s rush-hour traffic in a downpour. Within cities, we took metros, commuter trains, trams, buses, bike share, and walked…a lot.

From the perspective of a sustainable transportation advocate, we were treated to the complete “nice things” package: fast trains between cities, frequent rail and bus service inside them, and streets catering to human bodies more than SUVs. What surprised me, though, was the way these nice things coexist with growth patterns that look — in structural terms — uncomfortably familiar.

In this video 👆 from our high-speed rail into Madrid, you see familiar freeway traffic but also a local rail running alongside. This site may be more common in NYC, DC, Boston, and even Chicago but less so in the Western US.

Spain now operates one of the world’s largest high-speed networks. Spaniards reside inside a country roughly the size of Texas and enjoy about 4,000 kilometers of dedicated lines. This is Europe’s largest HSR system and one of only a handful of “comprehensive national networks” worldwide (Campos & de Rus, 2009; Perl & Goetz, 2015; UIC, 2024). Yet, like most of Europe, it has also seen a steady rise in car ownership. Across the EU, the average number of passenger cars per capita increased from 0.53 to 0.57 between 2011 and 2021, with Spain tracking that upward trend (Eurostat, 2023). Inland passenger-kilometers remain dominated by private cars, with rail — high-speed and conventional combined — taking a modest minority share (European Commission, 2021).

Spain, in other words, has both extensive HSR and rising car ownership. The tension between the pleasant micro-geographies of rail stations, sidewalks, and metro lines and the macro-geography of an ever-familiar car-dependent growth regime makes it interesting from an economic geography standpoint. HSR in Spain is not so much an alternative to growth but a particular way of organizing it.

America was once organized around rail. But our own car-dependent growth regime pushed it away. In the late nineteenth century, the United States was the HSR superpower of its time.

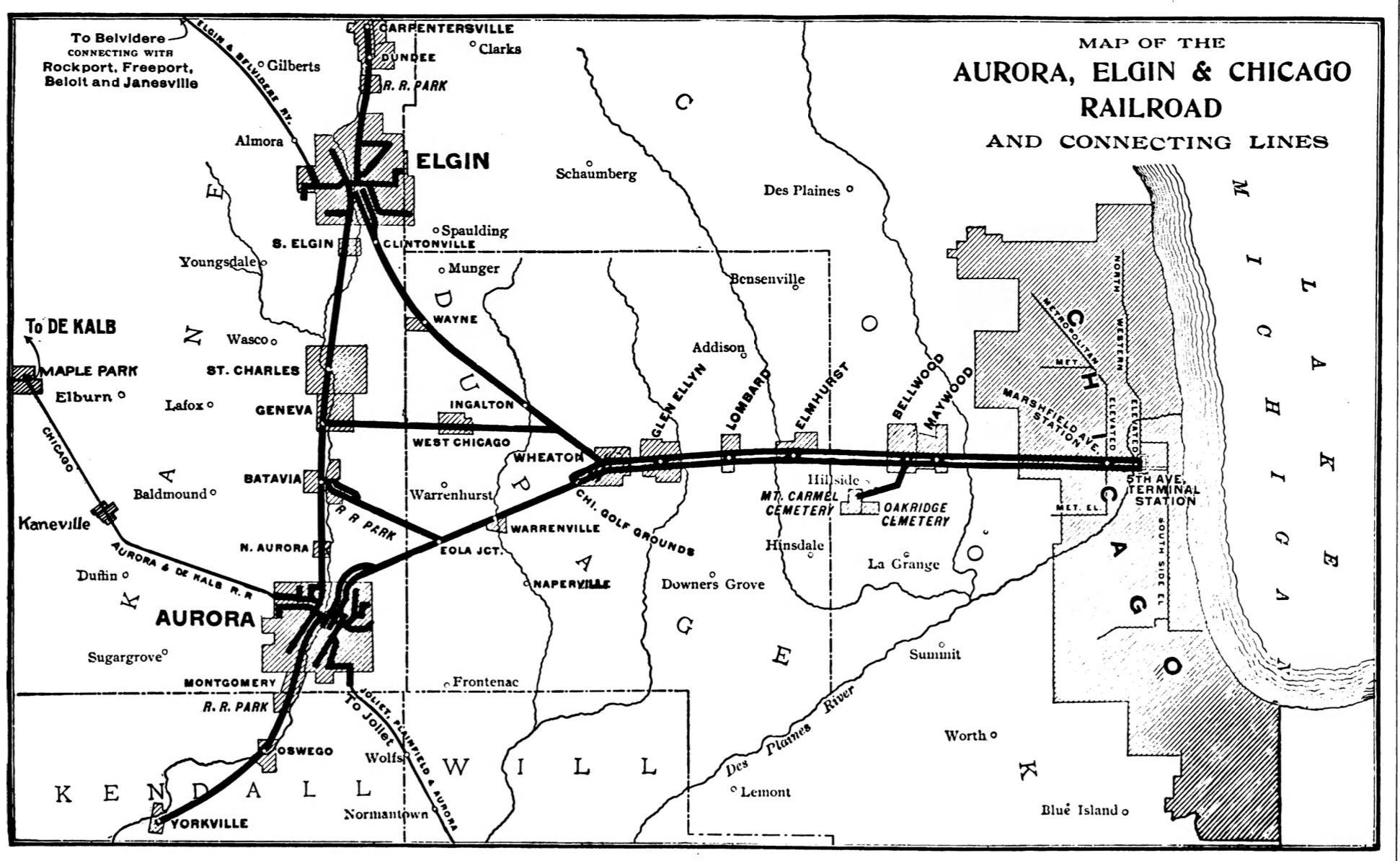

From the 1830s through the early twentieth century, a dense mesh of rail lines shortened distances across the continent. By 1916, the U.S. rail network peaked at roughly 254,000 route miles — enough track to circle the globe multiple times. It then went into steep decline under competition from cars and trucks (Stover, 1997; The RAND Corporation, 2008). Rail was not merely a mode of transport. It was the primary infrastructure for integrating an entire continent’s economy.

Chicago was the canonical beneficiary. William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis makes the case that rail-driven “time–space compression” did as much as natural endowments to elevate Chicago from muddy frontier town to the pivot of a continental system of grain, lumber, and meat (Cronon, 1991). Rail lines did not simply connect places that already mattered; they reorganized what mattered by funneling resources, capital, and people through specific nodes. Economic geography here is not just about location, but about which locations are made central by network design.

This “time–space compression” traces back to Karl Marx’s 1857–58 Grundrisse, where he described the “annihilation of space by time” as capitalism’s drive to overcome spatial barriers through faster transport like railroads to enable quicker turnover of capital. Geographer David Harvey formalized the term “time–space compression” in his 1989 The Condition of Postmodernity, building on Marx to analyze how nineteenth-century rail networks (alongside telegraphs) shrank perceived distances during the first major wave of compression from the mid-1800s to World War I.

At the metropolitan scale, those same rail technologies produced an earlier generation of “nice things” that sustainable transportation advocates now associate with Europe. Horsecar, cable car, and later electric streetcar networks radiated from downtowns into the countryside, creating early “rail suburbs” connected by frequent service and walkable main streets (Jackson, 1985; Fishman, 1987). Streetcar suburbs offered middle-class households a promise of a commuter train to a walkable compact neighborhood with quiet residential streets, relatively clean air, and quick access back to the city.

But these “nice things” were never neutral amenities. Rail suburbs became instruments of class and, in the U.S. context, racial segregation. (Jackson, 1985; Fishman, 1987) Access to frequent rail service and detached houses on leafy streets was tightly bound to property ownership and exclusionary practices. Chicago’s rail-driven boom reshaped hinterlands into “commodity frontiers.” It, like many other cities later, externalized environmental costs onto landscapes far from the city’s sidewalks, station concourses, and less than desirable living conditions.

RAILS, ROADS, AND REGIMES

The core paradox of economic growth is already visible here. Rail dramatically reduced transport costs and enabled agglomeration economies — thick labor markets, specialized firms, information spillovers — that enriched certain cities and classes. At the same time, those very efficiencies intensified resource extraction, spatial inequality, and political conflicts. Capital and power decided who could benefit and who would be pushed to the margins.

America once ran on rails — dense, local, and linked — its own version of the “nice things” seen in Spain. But they carried with them the costs of congestion and expansion, sending us on a different path for mobility.

The transition from rail to road in the twentieth-century United States is not just a story of transportation technology. It’s a story of how a country decided to scale itself.

As motor vehicles diffused in the early 1900s, they interacted with existing urban and regional patterns largely established by rail networks. Postwar sprawl is largely a confluence of car-based living. Rising incomes, coupled with finance institutions rewarding new developments and cheaply manufactured cars, led households and corporate firms to trade close proximity for space (Glaeser & Kahn, 2004). Cars did not invent the desire for separation from industrial cities, but they multiplied the potential configurations.

Federal policy amplified that shift. The 1956 National Interstate and Defense Highways Act created a 41,000-mile limited-access network funded primarily by federal fuel taxes. This embedded a new high-speed system on top of the pre-existing rail grid (National Archives, 2022; Weingroff, 1996). While railroads remained vital for freight, the intercity passenger market was increasingly organized around airports and interstates.

Kenneth Jackson’s Crabgrass Frontier documents how federal mortgage guarantees, tax incentives, and highway construction converged to make owner-occupied suburban homes the normative “good life” for white middle-class Americans (Jackson, 1985). Robert Fishman’s Bourgeois Utopias similarly traces how suburban landscapes became aspirational geographies of domestic desire separated from the din and drive of the urban mire, rising from London to Los Angeles (Fishman, 1987).

From an economic geography perspective, the postwar highway and aviation regime did not end agglomeration; it reconfigured it. Metropolitan regions sprawled outward along radial freeways and beltways. Airports became new nodes of connectivity, often surrounded by logistics parks and office clusters. The benefits of scale — large labor markets, diversified industries, hordes of consumers — remained, but the physical form of cities stretched into low-density, car-centric webs of cul-de-sacs.

This system has its own “nice things” that I enjoy every day: door-to-door convenience on your own schedule, cheap flights between distant cities, and a logistic network that will deliver almost anything in two days…or even the next hour. But it also hardened a built environment that is difficult to retrofit for different “nice things” like rail. The very success of car-based ascendence created a geography whose path dependence only leaves alternatives of prohibitive transcendence.

HSR projects worldwide tend to cluster where dense city pairs sit 300–800 km apart, with strong pre-existing travel demand and robust local transit systems (Campos and de Rus, 2009). National HSR strategies lead to “exclusive corridors,” “hybrid networks,” and “comprehensive national networks,” placing Spain firmly in the last camp (Perl and Goetz, 2015). It’s a country that is clearly attempting to knit together most major regional centers through high-speed lines.

Spain’s choice of a comprehensive network is legible on the ground. High-speed services plug directly into metropolitan rail systems like metros, trams, and intercity bus terminals. Stations are embedded in walkable fabrics rather than isolated off highway interchanges (or distant airports EasyJet often targets). That integration creates what Robert Cervero calls a “transit metropolis”: a region where a workable fit exists between transit services and urban form, so that high-capacity lines feed and are fed by dense, mixed-use neighborhoods (Cervero, 1998).

The economic geography of such a system is subtle. Spain’s HSR lines certainly reduce travel times between Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Seville, and other hubs. But the benefits do not simply diffuse evenly along the tracks. Research reviewing European cases shows that HSR is rarely “transformative” by itself. It mostly reinforces existing centers that can already capture agglomeration effects, especially when combined with supportive policies around land use and local transit. (Vickerman, 2018)

In practice, that means Madrid and Barcelona feel closer together in time and opportunity space, while smaller intermediate cities may or may not see proportional gains. Agglomeration economies intensify in the big nodes. Firms can draw on larger markets, workers can access more jobs, and weekend tourism can boom. At the same time, the network expands the radius within which people can consider “everyday” trips. Like a business meeting in Barcelona, or a spontaneous weekend in Valencia to attend the opera inside Calatrava’s futuristic Opera House.

This is where the growth paradox reappears. EU transport statistics show that, despite decades of rail investment, private cars still account for the majority of inland passenger-kilometers, with rail’s share modest but slowly increasing (European Commission, 2021). HSR does not eliminate car dependence so much as layer another growth-enabling system on top of it. The same reduction in time–space frictions that makes HSR delightful to ride also facilitates more and longer trips overall, even if some of them substitute for flights.

From the traveler’s perspective, a seamless itinerary from Barcelona to Valencia to Madrid feels like a triumph of infrastructure. From an economic geography lens, it is a particular resolution of the trade-off between agglomeration and externalities: more connectivity, more opportunity, more consumption, and more pressure on housing, landscapes, and local services.

If Spain’s network represents one way of managing the growth paradox, what would it take for the United States to “have nice things” again in the form of HSR?

At first glance, the answer seems straightforward: build lines between the major city pairs where distances are right and air travel is heavy — the Northeast Corridor, California’s Los Angeles–San Francisco line, maybe a Chicago-centered Midwest hub. The HSR literature broadly supports this corridor logic. Successful lines typically connect large, dense cities with strong existing flows, while weaker corridors struggle to generate enough ridership to justify their capital costs (Campos and de Rus, 2009; Perl and Goetz, 2015).

But those studies also assume something the United States often lacks: the local transit and land-use framework that lets HSR actually function as part of everyday mobility.

Hong Kong’s “Rail + Property” model is instructive here (Cervero and Murakami’s, 2009). By combining transit infrastructure with dense, mixed-use property development around stations — and capturing a share of the resulting land value increases — Hong Kong has been able to finance much of its rail network while creating environments where rail is the default option for many trips. The value capture mechanisms and zoning regimes are context-specific, but the broader lesson travels: HSR works best when station areas are intense agglomeration zones, not park-and-ride lots surrounded by arterials.

In much of the United States, however, rail stations — where they exist at all — sit in landscapes optimized for cars. Many potential HSR terminal sites are currently flanked by freeways, surface parking, and single-use zoning. Introducing high-speed service into such environments without altering their land-use and transit logics risks reproducing the patterns the research warns against: an expensive, symbolic infrastructure with limited transformative impact.

There is also the matter of scale. Low-density sprawl is, in part, the spatial expression of a car-and-highway technological regime. HSR requires a different spatial regime: one where trip volumes are high between specific nodes and where a substantial share of people and jobs cluster within catchments of good local transit. Without that, high-speed lines struggle to fill trains. Even worse, the per-passenger carbon and financial math becomes far less compelling.

None of this makes HSR impossible in the U.S. It just means that “nice things” are not only about technology or even capital. They are about the entire bundle of institutions, regulations, and growth patterns that give that technology something to plug into. The United States did this once with rail, then again with highways and aviation. Each time, the network we built reorganized economic geography in its own image.

HAVING NICE THINGS, ON PURPOSE

What I learned riding Spanish high-speed trains is not that the United States should abandon its HSR ambitions. Nor did the experience confirm a simple morality tale where Europe has virtuous trains and America has sinful freeways.

Instead, it underscored how transportation technologies are always embedded in larger growth regimes, and how those regimes come with paradoxes baked in. Rail made Chicago while it also helped empty hinterlands and deepen urban inequalities. Highways and airports made postwar American suburbs. They also locked in carbon-intensive sprawl and hollowed out many urban cores. Spain’s HSR enables low-carbon intercity travel and multiplies the number of places you can reasonably visit for a weekend, while car ownership quietly continues to rise.

While economic geography gives us a language of agglomeration economies, time–space compression, and path dependence, this question remains: “why can’t we have nice things?” It becomes less about copying Spanish trains and more about asking what kind of growth we are willing to organize ourselves around.

If the United States wants HSR to be one of its “nice things” again, it will have to be done on purpose and in sequence. Yes it requires corridors where the numbers pencil out, but also land-use reform around stations, reinvestment in local transit, and governance mechanisms. We’ll need structures that not only capture some of the value that rail can generate but also be used to perpetually fund the system.

It will mean recognizing that the very digital tools we already rely on — route planners, booking apps, algorithmic pricing — can either deepen our commitment to car-and-flight geographies or be leveraged to make multi-modal rail the path of least resistance. And in a country where residents in every metropolitan area reject attempts at building new airports, HSR is the only viable alternative. SeaTac’s former operations director once told me (over dinner on a train!) the he believes Denver’s 1995 airport may be America’s last new greenfield airport.

What’s frustrating is America knows how to do big transportation projects. We’ve done it before at different times, with different technologies, and with different winners. Spain was a reminder that “nice things” are possible and they’re never just amenities. They are big decisions about how to grow big. They’re also about who benefits from proximity and what kinds of landscapes we are willing to live with — even if and when the trains do arrive.

References

Campos, J., & de Rus, G. (2009). Some stylized facts about HSR: A review of HSR experiences around the world. Transport Policy.

Cervero, R. (1998). The transit metropolis: A global inquiry. Island Press.

Cervero, R., & Murakami, J. (2009). Rail and property development in Hong Kong: Experiences and extensions. Urban Studies.

Cronon, W. (1991). Nature’s metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. W. W. Norton.

European Commission. (2021). EU transport in figures: Statistical pocketbook 2021. Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurostat. (2023, May 30). Number of cars per inhabitant increased in 2021. Eurostat News.

Fishman, R. (1987). Bourgeois utopias: The rise and fall of suburbia. Basic Books.(Internet Archive)

Glaeser, E. L., & Kahn, M. E. (2004). Sprawl and urban growth. In J. V. Henderson & J. F. Thisse (Eds.), Handbook of regional and urban economics (Vol. 4, pp. 2481–2527). Elsevier.

Jackson, K. T. (1985). Crabgrass frontier: The suburbanization of the United States. Oxford University Press.(Internet Archive)

National Archives. (2022). National Interstate and Defense Highways Act (1956). U.S. National Archives.(National Archives)

Perl, A. D., & Goetz, A. R. (2015). Corridors, hybrids and networks: Three global development strategies for high speed rail. Journal of Transport Geography.

Stover, J. F. (1997). American railroads (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.(Internet Archive)

The RAND Corporation. (2008). The state of U.S. railroads: A review of capacity and performance. RAND.

UIC (International Union of Railways). (2024). HSR atlas 2024 edition. UIC.Vickerman, R. (2018). Can HSR have a transformative effect on the economy? Transport Policy, 62, 31–37.

Weingroff, R. F. (1996). Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956: Creating the Interstate System. Public Roads.