Hello Interactors,

It’s been awhile as I’ve been enjoying summer — including getting in my kayak to paddle over to a park to water plants. Time on the water also gets me thinking. Lately, it’s been about what belongs here, what doesn’t, and who decides? This week’s essay follows my trail of thought from ivy-covered fences to international borders. I trace how science, politics, and even physics shape our ideas of what’s “native” and what’s “invasive.”

INVASION, IVY, AND ICE

As I was contemplating this essay in my car at a stop light, a fireweed seedling floated through the sunroof. Fireweed is considered “native” by the U.S. Government, but when researching this opportunistic plant — which thrives in disturbed areas (hence it’s name) — I learned it can be found across the entire Northern Hemisphere. It’s “native” to Japan, China, Korea, Siberia, Mongolia, Russia, and all of Northern Europe. Because its primary dispersal is through the wind, it’s impossible to know where exactly it originated and when. And unlike humans, it doesn’t have to worry about borders.

So long as a species arrives on its own accord through wind, wings, currents, or chance — without a human hand guiding it — it’s often granted the status of “native.” Never mind whether the journey took decades or millennia, or if the ecosystem has since changed. What matters is that it got there on its own, as if nature somehow stamped its passport.

As long time Interactors may recall, I spend the summer helping water “native” baby plants into maturity in a local public green space. A bordering homeowner had planted an “invasive species”, English Ivy, years ago and it climbed the fence engulfing the Sword Ferns, Vine Maples, and towering Douglas Fir trees common in Pacific Northwest woodlands. A nearby concerned environmentalist volunteered to remove the “alien” ivy and plant “native” species through a city program called Green Kirkland. Some of the first Firs he planted are now taller than he is! Meanwhile, on the ground you see remnants of English Ivy still trying to muster a comeback. The stuff is tenacious.

This is also the time of year in the Seattle area when Himalayan Black Berries are ripening. These sprawls of arching spikey vines are as pernicious as they are delicious. Nativist defenders try squelching these invaders too. But unlike English Ivy, these “aliens” come with a sugary prize. You’ll see people walking along the side of roads with buckets and step stools trying their darnedest to pluck a plump prize — taking care not to get poked or pierced by their prickly spurs.

This framing of “invasive” versus “native” has given me pause like never before, especially as I witness armed, masked raids on homes and businesses carried out by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents. These government officials, who are also concerned and deeply committed citizens, see themselves as removing what they label “invasive aliens” — individuals they fear might overwhelm the so-called “native” population. As part of the Department of Homeland Security, they work to secure the “Homeland” from what is perceived as an invasion by unwanted human movement. In reflecting on this, I ask myself: how different am I from an ICE agent when I labor to eradicate plants I have been taught to call “invasive” while nurturing so-called “native” species back to health? Both of us are acting within a worldview that categorizes beings as either threats or treasures. At what cost, and with what consequences?

According to a couple other U.S. agencies (like the National Park Service and the U.S. Department of Agriculture) species are considered native if they were present before European colonization (i.e., pre-1492). The idea that a species is “native” if it was present before 1492 obviously reflects less a scientific ecological reality than a political opinion of convenience. Framing nativity through the lens of settler history rather than ecological process ignores not only millennia of Indigenous land stewardship, but prehistoric human introductions and natural migrations shaped by climate and geology. Trying pin down what is “native” is like picking up a squirming earthworm.

These little critters, which have profoundly altered soil ecosystems in postglacial North America, are often labeled “naturalized” rather than “native” because their arrival followed European colonization. Yet this classification ignores the fact that northern North America had no earthworms at all for thousands of years after the glaciers retreated. There were scraped away with the topsoil. What native species may exist in North America are confined to the unglaciated South.

What’s disturbing isn’t just the worms’ historical presence but the simplistic persistent narrative that ecosystems were somehow stable until 1492. How is it possible that so many people still insist it was colonial contact that supposedly flipped some ecological switch? In truth, landscapes have always been in motion. They’ve been shaped and reshaped by earth’s systems — especially human systems — long before borders were drawn. Defining nativity by a colonial decree doesn’t just flatten ecological complexity, it overwrites a deep history of entangled alteration.

MIGRATION, MOVEMENT, AND MEANING

If a monarch butterfly flutters across the U.S. border from Mexico, no one demands its papers. There are no butterfly checkpoints in Laredo or Yuma. It rides the wind northward, tracing ancient pathways across Texas, the Midwest, all the way to southern Canada. The return trip happens generations later — back to the oyamel forests in the state of Michoacán. This movement is a marvel. It’s so essential we feel compelled to watch it, map it, and even plant milkweed to help it along. But when human beings try to make a similar journey on the ground — fleeing drought, violence, or economic collapse — we call it a crisis, build walls, and question their right to belong.

This double standard starts to unravel when you look closely at the natural world. Species are constantly on the move. Some of the most astonishing feats of endurance on Earth are migratory: the Arctic tern flies from pole to pole each year; caribou migrate thousands of miles across melting tundra and newly paved roads.1 GPS data compiled in Where the Animals Go shows lions slipping through suburban gardens and wolves threading through farmland, using hedgerows and railways like interstates.2 Animal movement isn’t the exception; it’s the ecological norm.

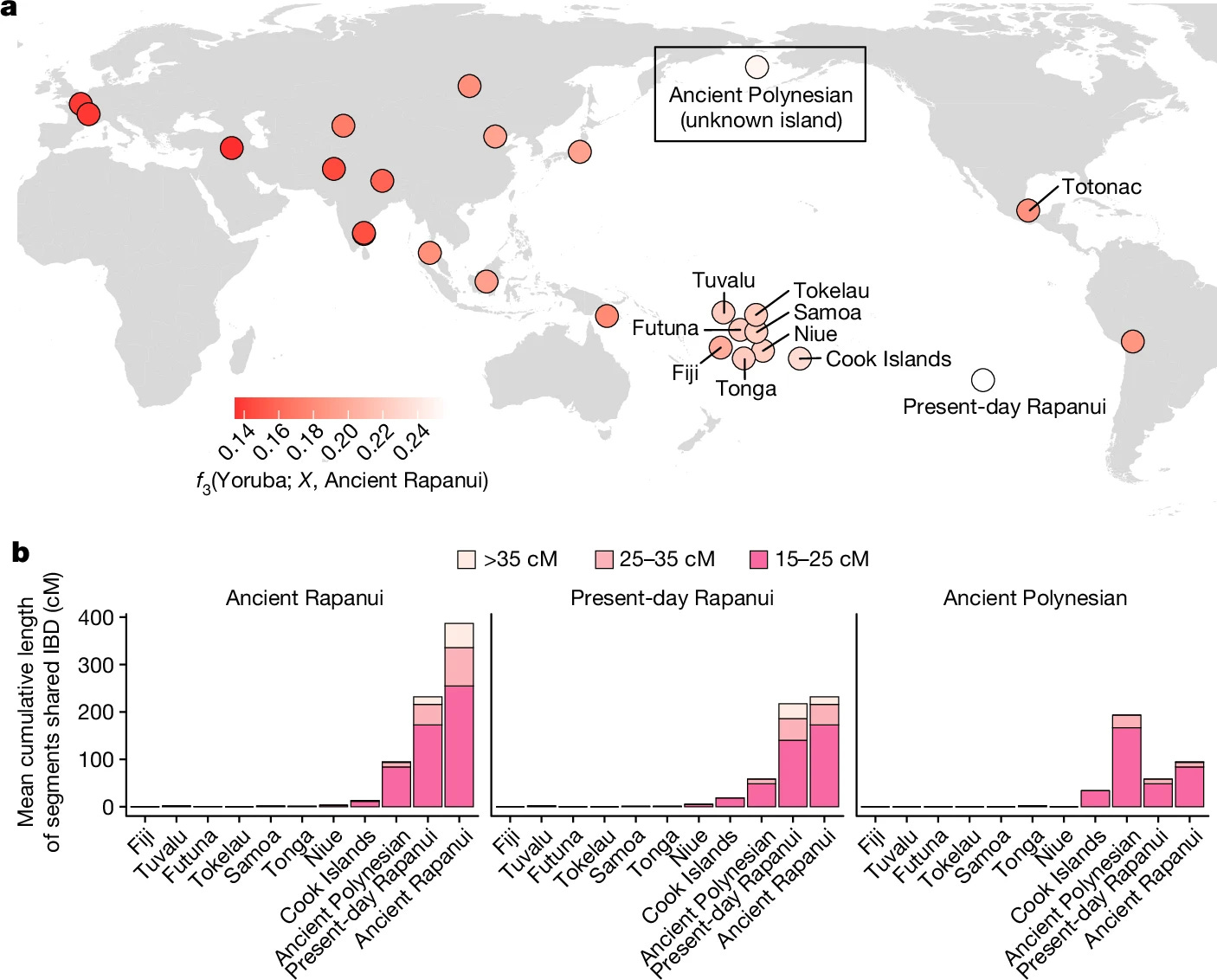

And it’s not just animals. Plants, too, are masters of mobility. A single seed can cross oceans, whether on the back of a bird, in a gust of wind, or tucked into a canoe by a human hand. In one famous case, researchers once proposed that a tree found on a remote Pacific Island must have arrived via floating debris. But later genetic and archaeological evidence suggested a different story: it may have arrived with early Polynesian voyagers — people whose seafaring knowledge shaped entire ecosystems across the Pacific.

DNA evidence and phylogeographic studies (how historical processes shape the geographic distribution of genetic lineages within species) now support the idea that Polynesians carried plants such as paper mulberry, sweet potato, taro, and even some trees across vast ocean distances well before the Europeans showed up. What was once considered improbable — human-mediated dispersal to incredibly beautiful and remote islands — is now understood as a core part of Pacific ecological and cultural history.

Either way, that plant didn’t ask to be there. It simply was. And with no obvious harm done, it was allowed to stay.

We humans can also often conflate our inability to perceive harm with the idea that a species “belongs.” We tend to assume that if we can’t see, measure, or immediately notice any negative impact a species is having, then it must not be causing harm — and therefore it “belongs” in the ecosystem. But belonging is contextual. It can be slow to reveal and is rarely absolute.

British ecologist and writer Ken Thompson has spent much of his career challenging our tidy categories of “native” and “invasive.” In his book Where Do Camels Belong?, he reminds us that the “belonging” question is less about biology than bureaucracy.3 Camels originated in North America and left via the Bering land bridge around 3–5 million years ago. They eventually domesticated in the Middle East about ~3,000–4,000 years ago to be used for transportation, milk, and meat. Then, in the 19th century, British colonists brought camels to Australia to help explore and settle the arid interior. Australia is now home to the largest population of feral camels in the world. So where, exactly, do they “belong”? Our ecological borders, like our political ones, often make more sense on a map than they do in the field.

Even the language we use is steeped in militaristic and xenophobic overtones. Scottish geographer Charles Warren has written extensively on how conservation debates are shaped by the words we choose. In a 2007 paper, he argues that terms like invasive, alien, and non-native don’t just describe, but pass judgment.4 They carrying moral and political weight into what should be an ecological conversation. They conjure feelings of threat, disorder, and contamination. When applied to plants, they frame restoration as a battle. With people, they prepare the ground for exclusion.

Which is why I now hesitate when I yank ivy or judge a blackberry bramble. I still do it because I believe in fostering ecological resilience and am sensitive to slowing or stopping overly aggressive and harmful plants (and animals). But now I do it more humbly, more questioningly. What makes something a threat, and who gets to decide? What if the real harm lies not in movement of species, but in the stories we tell about it?

MIGRATION, MYTHS, AND MATTER

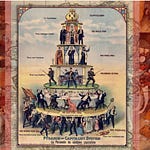

The impulse to define who belongs and who doesn’t isn't limited to the forest floor. It echoes in immigration policy, in the architecture of the border wall, and in the sterile vocabulary of "population control." Historians of science Sebastian Normandin and Sean Valles have examined how science, politics, and social movements intersect. In a 2015 paper, they show that many conservation policies we take for granted today — ostensibly about protecting ecosystems — emerged from the same ideological soil that nourished eugenics programs and early anti-immigration campaigns.5 What began as a concern for environmental balance often mutated into a desire for demographic purity.

We see this convergence in the early 1900s, when the U.S. Dillingham Commission launched an exhaustive effort to classify immigrants by race, culture, and supposed “fitness” for American life. Historian Robert Zeidel, in his 2004 account of U.S. immigration politics, details how the Dillingham Commission’s findings hardened the notion that certain groups — like certain species — are inherently better suited to thrive in the nation’s “ecological” and cultural landscape.6 Their conclusions fueled the 1924 Immigration Act, one of the most restrictive in U.S. history, and laid groundwork for a century of racialized immigration policy.

These ideas didn’t stay in the realm of policy. They seeped into science. Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, built racial categories into the very fabric of biological classification. Historian of science Lisbet Koerner, in her 1999 study of Carl Linnaeus, shows how his taxonomy reflected and reinforced 18th-century European ideals of empire and control.7 His system sorted not only plants and animals, but people. Nature, under his framework, was not only to be known but to be ordered. As Linneaus often said, "God created, Linnaeus organized." Brad observes that Carl also spoke in the third person.

The Linnaeus legacy lingers. Legal scholar and sociologist Dorothy Roberts8 and anthropologist Robert Sussman9 both argue that modern science has quietly resurrected racial categories in genetic research, often under the guise of ancestry testing or precision medicine. But race, like “nativity,” is not a biological fact — it’s a social construct. Anthropologist Jonathan Marks10 and geneticist David Reich11 reach the same conclusion from different directions: the human genome tells a story not of fixed, isolated groups, but of constant migration, mixing, and adaptation.

This is why defining species as “native” or “invasive” based on a colonial timestamp like 1492 is more than just a scientific shortcut. It’s a worldview that imagines a pristine past disrupted by foreign intrusion. This myth is mirrored in nationalist movements around the globe — including the troubling MAGA blueprint: Project 2025.

When we talk about securing borders, protecting bloodlines, or restoring purity, we’re often echoing the same flawed logic that labels blackberry and ivy as existential threats, while ignoring the systems that truly destabilize ecosystems — like extractive capitalism, industrial agriculture, and global trade. But even these forces may not be purely ideological. As complexity theorist Yaneer Bar-Yam, founder of the New England Complex Systems Institute, has argued, large-scale societal and ecological patterns often emerge not through top-down intent, but through the bottom-up dynamics of complex systems under stress.12

These dynamics are shaped by entropy — not in the popular sense of disorder, but as the tendency of energy and influence to disperse across systems in unpredictable ways as complexity increases. In this view, what we experience as exploitation or collapse may also be the inevitable result of a world growing too intricate to govern by simple, centralized rules.

Consider those early Polynesians. Perhaps we best think of them as complex, intelligent, tool-bearing animals who crossed vast oceans long before Europe entered the story. They didn't defy nature, they expressed it. They simply scaled up the same dispersal seen in wind-blown seeds or migratory birds. Their movement, like that of camels, fireweed, or monarchs, reminds us that life is always pushing outward, but because it can. This outward motion follows physics.

Even in an open system like Earth, the Second Law of Thermodynamics holds sway. Energy flows in and life finds ever more complex ways to move it along. A sunbeam warms a rock, releasing energy into the air above. That warmth lifts air, forming wind. The wind carries seeds across fields and fence lines, scattering the future wherever friction allows. Seeds take root, drawing in sunlight, water, and minerals. They build structure to move energy forward. Muscles twitch as animals rise to consume that energy then follow warmth, water, or instinct. Wings of the bird lift so it may fly. Herds of the plain press so they may migrate.

These patterns stretch across microseconds, minutes, and millennia — creeks, crevices, and continents. And eventually, humans launch canoes in the ocean tracing the same thermodynamic pull, riding currents of wind, wave, desire, and need. None of it defies nature. It is nature. It can be seen as different forms of energy dispersing through motion, life, and relationship at different scales.

One of the first scientists to recognize this was a Belgian chemist in the 1970s who saw something radical in the chaos of fluctuations and energy flows in nonequilibrium chemical systems: that complexity could arise not despite entropy, but because of it. Ilya Prigogine called these emergent forms dissipative structures — systems that spontaneously self-organize to transform and disperse energy more efficiently. A familiar example is a snowflake, which forms highly ordered crystal structures as water vapor crystallizes under just the right conditions. This beautiful pattern represents order emerging directly from the molecular chaos of a winter storm.

Extending this idea, we might begin to see migration, dispersal, and adaptation not as disruptions or disturbances, but as natural expressions of complex systems tirelessly working toward order. These processes are ways in which living systems unfold, expand, and improvise — dynamically responding to the flows of energy they must transform to sustain themselves and their environments.

To call such movement unnatural is to forget that we, too, are part of nature’s restless patterning. The real challenge isn’t to freeze the world in place, but to understand these flows so we might shape them with care, rather than react to them with fear.

To be clear: not all movement is benign. Some species — like kudzu or cane toads — have caused undeniable ecological damage. But the danger lies not in movement itself, but in the conditions of arrival and the systems of control. Climate change, habitat destruction, and globalization create the disturbances that opportunistic species exploit. They don’t “invade” so much as arrive when the door is already open.

And entropy doesn’t mean indifferent inevitability, and complexity doesn’t mean plodding passivity. Living systems are capable of generating counter-forces like cooperative networks, defensive alliances, and feedback loops. This form of collective actions resists domination and reasserts balance. Forests shade out overzealous colonizers, coral fish guard polyps from overgrazers, microbial webs starve out pathogens. Agency, be it a fungus or a human community, operates within the same flow of energy, shaping it toward persistence, resilience, and sometimes justice.

So, when I pull ivy or water a fern, I do it with a different awareness now. I see myself not as a border guard, but as one actor in a much older drama — a participant in the ceaseless give-and-take through which living systems maintain their balance. My hands are not outside the flow, but in it, nudging here, ceding there, trying to tip the scales toward diversity, reciprocity, and resilience. It’s not purity I’m after, but possibility: a landscape, human and more-than-human, capable of adapting to what comes next.

Kessler, R. (2011). The great migrations: Animals on the move. Smithsonian Magazine.

Cheshire, J., & Uberti, O. (2016). Where the animals go: Tracking wildlife with technology in 50 maps and graphics. W. W. Norton.

Thompson, K. (2014). Where do camels belong?: The story and science of invasive species. Profile Books.

Warren, C. (2007). Perspectives on the ‘alien’ versus ‘native’ species debate: A critique of concepts, language and practice. Progress in Human Geography

Normandin, S., & Valles, S. (2015). How a network of conservationists and population control activists created the contemporary US anti-immigration movement. Endeavor. Elsevier.

Zeidel, R. F. (2004). Immigrants, progressives, and exclusion politics: The Dillingham Commission, 1900–1927. Northern Illinois University Press.

Koerner, L. (1999). Linnaeus: Nature and nation. Harvard University Press.

Roberts, D. (2012). Fatal invention: How science, politics, and big business recreate race in the twenty-first century. The New Press.

Sussman, R. W. (2014). The myth of race: The troubling persistence of an unscientific idea. Harvard University Press.

Marks, J. (1995). Human biodiversity: Genes, race, and history. Aldine de Gruyter.

Reich, D. (2018). Who we are and how we got here: Ancient DNA and the new science of the human past. Pantheon.

Bar-Yam, Y. (2004). Multiscale complexity/entropy. Advances in Complex Systems.