Hello Interactors,

Every week it seems to get harder to ignore the feeling that we're living through some major turning point — politically, economically, environmentally, and even in how our cities are taking shape around us. Has society seen this movie before? Spoiler: we have, and it has many sequels.

History doesn't repeat exactly, but it sure rhymes, especially when competition for power increases, climates collapse, and the urban fabric unravels and rewinds. Today, we'll sift through history’s clues, peek through some fresh conceptual lenses, and consider why the way we frame these shifts matters — maybe more now than ever.

PRESSURE POINTS AT URBAN JOINTS

Let’s ground where we all might be historically speaking. Clues from long-term historical patterns suggests social systems go through periodic cycles of integration, expansion, and crisis. Historical quantitative data reveals recurring waves of structural-demographic pressure — moments when inequality, elite overproduction, and resource strain converge to produce instability.

By quantitative historian Peter Turchin’s account, we are currently drifting through some kind of inflection point. His 2010 essay in Nature anticipated the early 2020s as a period of peak instability that started around 1970. That’s when people earning advanced degrees, entering law, finance, media, and politics skyrocketed from the 1970s onward. Meanwhile, the number of elite positions (like Senate seats, Supreme Court clerkships, high level corporate positions) remained fixed or even shrank. This created decades of increased income inequality, elite competition, and declining public trust that created conditions for events like the rise of Trump, polarization, and institutional gridlock.1

The symptoms are familiar to us now, and they are markers that echo previous systemic ruptures in U.S. history.

In the 1770s, colonial grievances and elite competition led to a historic revolutionary realignment. It also coincided with poor harvests and food insecurity that amplified unrest. The 1860s brought civil war driven by slavery and sectional conflict. It too occurred during a period of climate volatility and crop failures. The early 20th century saw the Gilded Age unravel into labor unrest and the Great Depression, following years of drought and economic collapse in the Dust Bowl. The 1960s through 1980s unleashed social protest, stagflation, and the shift toward neoliberal governance amid fears of resource scarcity and rising pollution. In each case, ecological shocks layered onto political and economic pressures — making transformation not only likely, but necessary.

Spatial patterns shifted alongside these political ruptures — from rail hubs and company towns to low flung suburban rings and high-rise financialized skylines. Cities can be both staging grounds creating these shifts and mirrors reflecting them. As material and symbolic anchors of society, they reflect where systems are strained — and where new forms may soon take root.

Urban transformation today is neither orderly nor speculative — it is reactive. These socio-political, economic, and ecological shifts have fragmented not just the city, but the very frameworks we use to understand it. And with urban scale theory as a measure, change is accelerating exponentially. This means our conceptual tools to understand these shifts best respond just as quickly.

Let’s dip into the academic world of contemporary urban studies to gauge how scholars are considering these shifts. Here are three lenses that seem well-suited to consider our current landscape…or perhaps those my own biases are attracted to.

Urban Political Ecology. This sees the city as a socio-natural process — shaped by uneven flows of energy, capital, and extraction. This approach, developed by critical geographers like Erik Swyngedouw and Maria Kaika, highlights how environmental degradation is often tied to social inequality and political neglect.2 Matthew Gandy, an urban geographer who blends political theory and environmental history, adds to this view. He shows how infrastructure — from water systems to waste networks — shapes urban nature and power.3

The Jackson, Mississippi water crisis, for example, revealed how ecological stress and decades of disinvestment resulted in a disheartening breakdown. In 2022, flooding overwhelmed Jackson's aging water system, leaving tens of thousands without safe drinking water — but the failure had been decades in the making. Years of underfunding, political neglect, and systemic racism had hollowed out the city’s infrastructure.

Or take Musk's AI data center called Colossus in Memphis, Tennessee. It’s adjacent to historically Black neighborhoods and uses 35 methane gas-powered turbines that emit harmful nitrogen oxides (NOx) and other pollutants. It’s reported to be operating without proper permits and contributes to air quality issues these communities already have long experienced. These crises are vivid cases of what urban political ecologists warn about: how marginalization and disinvestment manifest physically in infrastructure failure, disproportionately affecting already vulnerable populations.

Platform Urbanism. This explains much of the growing visible and invisible restructuring of urban space. From delivery networks to sidewalk surveillance, digital platforms now shape land use and behavioral patterns. Urban theorists like Sarah Barns and geographer Agnieszka Leszczynski describe these systems as shadow planners — zoning isn’t just on paper anymore; it’s encoded in app interfaces and service contracts.4 Shoshana Zuboff, a social psychologist and scholar of the digital economy, pushes this further.

She argues that platforms are not just intermediaries but extractive infrastructures. They’re designed to shape behavior and monetize it at scale.5 As platforms replace institutions, their spatial footprint expands. For example, Amazon has redefined regional land use by building vast fulfillment centers and reshaping delivery logistics across suburbs and exurbs. Or look at Uber and Lyft. They’ve altered curbside usage and traffic patterns in major cities without ever appearing on official planning documents. These changes demonstrate how digital infrastructure now directs physical development — often faster than public institutions can respond.

Neoliberal Urbanism. Though widely critiqued, this remains the dominant lens. Despite growing backlash, deregulated markets, privatized services, and financialized real estate continue to shape planning logic and policy defaults. Urban theorists like Neil Brenner and economic geographer Jamie Peck describe this as a shift from managerial to entrepreneurial cities — where the suburbs sprawl, the towers rise, and exclusion is reproduced not by public design input, but by tax codes, ownership models, and legacy zoning.6 Like many governing systems, the default is to preserve the status quo. Institutions, once entrenched, tend to perpetuate existing frameworks — even in the face of mounting social or ecological stress.

For example, in many U.S. cities, exclusionary zoning laws have long restricted the construction of multi-family housing in favor of single-family homes — limiting supply, reinforcing segregation, and driving up housing costs. Even modest attempts at reform often meet local resistance, revealing how deeply these rules are woven into planning culture.

These lenses aren’t just theoretical — they are descriptively powerful. They reflect what is, not what could be. But describing the present is only the first step.

NEW NOTIONS OF URBAN MOTIONS

It’s worth considering alternative conceptual lenses rising in relevance. These are not yet changing the shape of cites at scale, but they are shaping how we think about our urban futures. Historically, new conceptual lenses have often emerged in the wake of the kind of major social and spatial disruptions already covered.

For example, the upheavals of the 19th century. This rapid industrialization, urban crowding, and public health crises gave rise to modern, industrial-era city planning. The mid-20th century crises helped institutionalize zoning and modernist design, while the neoliberal turn of the late 20th century elevated market-driven planning models.

Emerging conceptual lenses of the 21st century are grounded in complexity, care, informality, and computation. These are responses to the fragmented plurality of our planetary plight — characteristic of the current calamity of our many crises, or polycrisis. Frameworks for thinking and imagining cities gain traction in architecture and planning studios, classrooms, online and physical activist spaces, and experimental design projects. They’re not yet dominant, but they are gaining ground. Here are a few I believe to be particularly relevant today.

Assemblage Urbanism. This lens views cities not as coherent wholes, but as contingent networks that are always in the making. The term "assemblage" comes from philosophy and anthropology. It refers to how diverse elements — people, materials, policies, and technologies — come together in temporary, evolving configurations. This lens resists top-down models of urban design and instead sees cities as patchworks of relationships and improvisations.

Introduced by scholars like Ignacio Farias, an urban anthropologist focused on technological and infrastructural urban change, and AbdouMaliq Simone, a sociologist known for his work on African cities and informality, this approach offers a vocabulary for complexity and contradiction.78 It examines cities made of sensors and encampments, logistics hubs and wetlands.

Colin McFarlane, a geographer who studies how cities function and evolve — especially in places often overlooked in mainstream planning — shows how urban learning spreads through these networks that cross places and scales.9 As the built environment becomes more fragmented and multi-scalar, this lens offers a way to map the friction and fluidity of emergent urban life.

Postcolonial and Feminist Urbanisms. This lens challenges who gets to define the city, and how. Ananya Roy, a scholar of global urbanism and housing justice, Jennifer Robinson, a geographer known for challenging Western-centric urban theory, and Leslie Kern, a feminist urbanist focused on gender and public space, all center the voices and experiences often sidelined by mainstream planning: women, racialized communities, and the so-called Global South.101112 These are regions, not always in the Southern Hemisphere, that have historically been colonized, exploited, or marginalized by dominant empires of the so-called Global North.

These frameworks put care, informality, and embodied experience in the foreground — not as soft supplements to be ‘considered’, but as central to urban survival. They ask: whose knowledge counts and whose mobility is prioritized? In a world of precarity and patchwork governance, these lenses offer both critique and more fair and balanced paths forward.

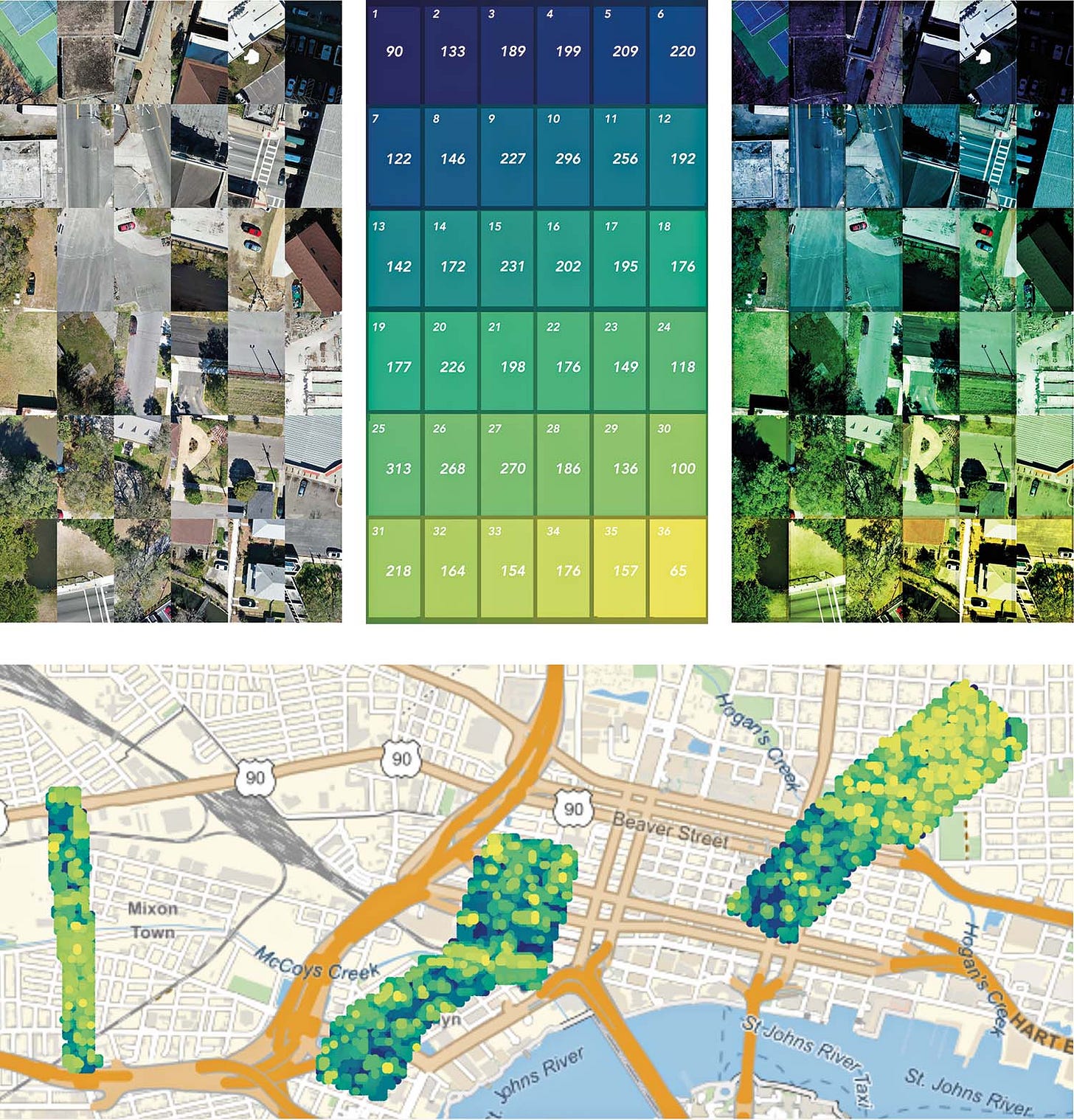

Typological and Morphological Studies. These older, traditional lenses are reemerging through new tools. Once associated with the static physical form of cities, these traditions are finding renewed relevance through machine learning and spatial data. These approaches originate from architectural history and geography, where typology refers to recurring building patterns, and morphology to the shape and structure of urban space. Scholars like Saverio Muratori and Gianfranco Caniggia, both architects, emphasized interpreting urban fabric as a continuous, evolving record of social life.13

As mentioned last week, British geographer M. R. G. Conzen introduced town-plan analysis, a method for understanding how plots and street systems change over time. Today, this lineage is extended by Laura Vaughan, an urbanist who studies how spatial form reflects social patterns, and Geoff Boeing, a planning scholar using computational tools to analyze and visualize urban form also mentioned last week.14

AI models now interpret urban imagery, using historical patterns to predict future trends. This approach is evolving into a kind of algorithmic archaeology. However, unchecked it could reinforce existing spatial norms instead of challenging them. This stresses the importance of reflection, ethics, and debate about the implications and outcomes of these models…and who benefits most.

While these lenses don’t yet dominate design codes or capital flows, they do shape how we think and talk about our cities. And isn’t that where all transformation begins?

CHOOSING PATHS IN AFTERMATHS

Concepts don’t emerge in a vacuum. History shows us how they arise from the anxiety and urgency of uncertainty. As historian Elias Palti reminds us, frameworks gain traction when once dominant and grounding meanings begin crumbling under our feet. That’s when we invent or seek new ways to make sense of our shifting ground.

Donna Haraway, a pioneering feminist scholar in science and technology studies, urges us to stay with this mess and imagine new futures from within it. She describes these moments as opportunities to 'stay with the trouble' — to resist closure, dwell in complexity, and imagine alternatives from within the uncertainty.15

Historically, moments of systemic crisis — from the 1770s to the 1840s, the 1930s to the 1960s — have sparked shifts not just in spatial form, but in the conceptual tools used to understand and design it. Revolutionary and reformist movements have often carried with them new ways of seeing: Enlightenment ideals, socialist critiques, environmental consciousness, and decolonial frameworks. We may be living through another such moment now — where the cracks in the old invite us to rethink the categories that built it.

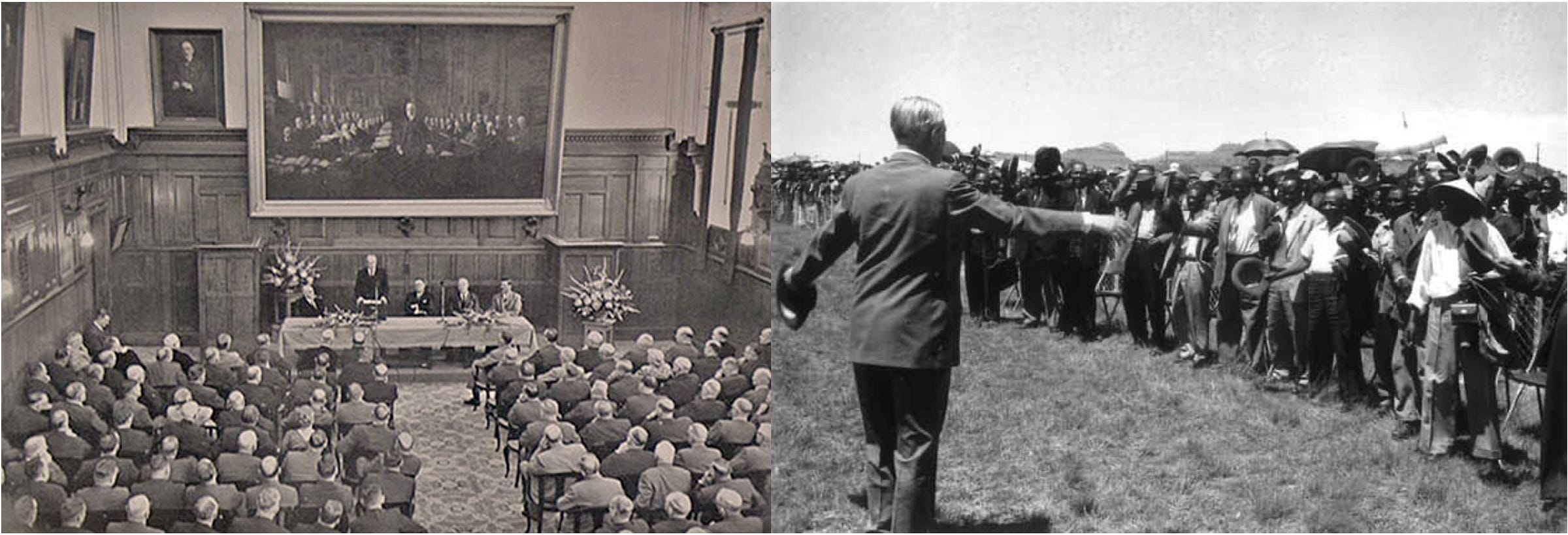

In 1960, five years before I was born, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan gave a speech called “Wind of Change”. It was a public acknowledgement of the decline of British empire and the rise of anti-colonial nationalism around the globe. Delivered in apartheid South Africa, it was a rare moment of elite recognition that a global shift in political and spatial order was already underway. Britain’s imperial dominance was fading just as American dominance was solidifying.

Today, we see echoes of that moment. The U.S. is facing economic fragmentation, growing inequality, and diminishing global legitimacy, while China asserts itself as a counterweight. Resistance and unrest in places like Palestine, Ukraine, Yemen, Congo, Sudan, Kashmir, (and many more) mirror the turbulence of previous historic transitions. Once again, the global “winds of change” are shifting, strengthening, and unpredictably swirling. It can be disorienting.

But the frameworks I’ve outlined above are more than cold attempts at academic neutral observations, they can serve as lenses of orientation. They help guide what we see, what we measure, and what we ignore. And in doing so, they shape what futures become possible.

Some frameworks are widely used but lack ethical depth. Others are less common but are full of imagination and ethical reconfigurations. The lenses we prioritize in public policy, early education, design, and discussion will shape whether our future systems perpetuate existing inequalities or purge them.

This is not just an academic choice. It's a civic one.

While macro forces of capital or climate are beyond our control, it is possible to shape the narratives that impact our responses. The question remains whether space should continue being optimized for logistics and financial speculation, or if there is potential to focus on ecological repair, historical redress, and spatial justice.

Future developments will be influenced by current thoughts. The most impactful decision in urban design may come down to us all being more intentional in selecting the concepts that guide us forward.

REFERENCES

Turchin, P. (2010). Political instability may be a contributor in the coming decade. Nature.

Kaika, M., & Swyngedouw, E. (2000). Fetishizing the modern city: The phantasmagoria of urban technological networks. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research.

Gandy, M. (2004). Concrete and Clay: Reworking Nature in New York City. MIT Press.

Barns, S., & Leszczynski, A. (2020). Platform urbanism: Negotiating platform ecosystems in connected cities. Urban Studies.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs.

Peck, J., & Brenner, N. (2009). Neoliberal urbanism: Models, moments, mutations. SAIS Review.

Farias, I., & Bender, T. (Eds.). (2010). Urban Assemblages: How Actor-Network Theory Changes Urban Studies. Routledge.

Simone, A. (2004). For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities. Duke University Press.

McFarlane, C. (2011). Learning the City: Knowledge and Translocal Assemblage. Wiley-Blackwell.

Roy, Ananya. City Requiem, Calcutta: Gender and the Politics of Poverty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Robinson, Jennifer. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Kern, Leslie. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World. London: Verso, 2020.

Muratori, S. (1959). Studi per una operante storia urbana di Venezia. Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato.

Vaughan, L. (2015). Suburban Urbanities: Suburbs and the Life of the High Street. UCL Press.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.