Hello Interactors,

This week, the European Space Agency launched a satellite to "weigh" Earth's 1.5 trillion trees. It will give scientists deeper insight into forests and their role in the climate — far beyond surface readings. Pretty cool. And it's coming from Europe.

Meanwhile, I learned that the U.S. Secretary of Defense — under Trump — had a makeup room installed in the Pentagon to look better on TV. Also pretty cool, I guess. And very American.

The contrast was hard to miss. Even with better data, the U.S. shows little appetite for using geographic insight to actually address climate change. Information is growing. Willpower, not so much.

So it was oddly clarifying to read a passage Christopher Hobson posted on Imperfect Notes from a book titled America by a French author — a travelogue of softs. Last week I offered new lenses through which to see the world, I figured I’d try this French pair on — to see America, and the world it effects, as he did.

PAPER, POWER, AND PROJECTION

I still have a folded paper map of Seattle in the door of my car. It’s a remnant of a time when physical maps reflected the reality before us. You unfolded a map and it innocently offered the physical world on a page. The rest was left to you — including knowing how to fold it up again.

But even then, not all maps were neutral or necessarily innocent. Sure, they crowned capitals and trimmed borders, but they could also leave things out or would make certain claims. From empire to colony, from mission to market, maps often arrived not to reflect place, but to declare control of it. Still, we trusted it…even if was an illusion.

I learned how to interrogate maps in my undergraduate history of cartography class — taught by the legendary cartographer Waldo Tobler. But even with that knowledge, when I was then taught how to make maps, that interrogation was more absent. I confidently believed I was mediating truth. The lines and symbols I used pointed to substance; they signaled a thing. I traced rivers from existing base maps with a pen on vellum and trusted they existed in the world as sure as the ink on the page. I cut out shading for a choropleth map and believed it told a stable story about population, vegetation, or economics. That trust was embodied in representation — the idea that a sign meant something enduring. That we could believe what maps told us.

This is the world of semiotics — the study of how signs create meaning. American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce offered a sturdy model: a sign (like a map line) refers to an object (the river), and its meaning emerges in interpretation. Meaning, in this view, is relational — but grounded. A stop sign, a national anthem, a border — they meant something because they pointed beyond themselves, to a world we shared.

But there are cracks in this seemingly sturdy model.

These cracks pose this question: why do we trust signs in the first place? That trust — in maps, in categories, in data — didn’t emerge from neutrality. It was built atop agendas.

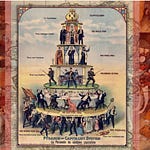

Take the first U.S. census in 1790. It didn’t just count — it defined. Categories like “free white persons,” “all other free persons,” and “slaves” weren’t neutral. They were political tools, shaping who mattered and by how much. People became variables. Representation became abstraction.

Or Carl Linnaeus, the 18th-century Swedish botanist who built the taxonomies we still use: genus, species, kingdom. His system claimed objectivity but was shaped by distance and empire. Linnaeus never left Sweden. He named what he hadn’t seen, classified people he’d never met — sorting humans into racial types based on colonial stereotypes. These weren’t observations. They were projections based on stereotypes gathered from travelers, missionaries, and imperial officials.

Naming replaced knowing. Life was turned into labels. Biology became filing. And once abstracted, it all became governable, measurable, comparable, and, ultimately, manageable.

Maps followed suit.

What once lived as a symbolic invitation — a drawing of place — became a system of location. I was studying geography at a time (and place) when Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and GIScience was transforming cartography. Maps weren’t just about visual representations; they were spatial databases. Rows, columns, attributes, and calculations took the place of lines and shapes on map. Drawing what we saw turned to abstracting what could then be computed so that it could then be visualized, yes, but also managed.

Chris Perkins, writing on the philosophy of mapping, argued that digital cartographies didn’t just depict the world — they constituted it. The map was no longer a surface to interpret, but a script to execute. As critical geographers Sam Hind and Alex Gekker argue, the modern “mapping impulse” isn’t about understanding space — it’s about optimizing behavior through it; in a world of GPS and vehicle automation, the map no longer describes the territory, it becomes it.

Laura Roberts, writing on film and geography, showed how maps had fused with cinematic logic — where places aren’t shown, but performed. Place and navigation became narrative. New York in cinema isn’t a place — it’s a performance of ambition, alienation, or energy. Geography as mise-en-scène.

In other words, the map’s loss of innocence wasn’t just technical. It was ontological — a shift in the very nature of what maps are and what kind of reality they claim to represent. Geography itself had entered the domain of simulation — not representing space but staging it. You can simulate traveling anywhere in the world, all staged on Google maps. Last summer my son stepped off the train in Edinburgh, Scotland for the first time in his life but knew exactly where he was. He’d learned it driving on simulated streets in a simulated car on XBox. He walked us straight to our lodging.

These shifts in reality over centuries weren’t necessarily mistakes. They unfolded, emerged, or evolved through the rational tools of modernity — and for a time, they worked. For many, anyway. Especially for those in power, seeking power, or benefitting from it. They enabled trade, governance, development, and especially warfare. But with every shift came this question: at what cost?

FROM SIGNS TO SPECTACLE

As early as the early 1900s, Max Weber warned of a world disenchanted by bureaucracy — a society where rationalization would trap the human spirit in what he called an iron cage. By mid-century, thinkers pushed this further.

Michel Foucault revealed how systems of knowledge — from medicine to criminal justice — were entangled with systems of power. To classify was to control. To represent was to discipline. Roland Barthes dissected the semiotics of everyday life — showing how ads, recipes, clothing, even professional wrestling were soaked in signs pretending to be natural.

Guy Debord, in the 1967 The Society of the Spectacle, argued that late capitalism had fully replaced lived experience with imagery. “The spectacle,” he wrote, “is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.”

Then came Jean Baudrillard — a French sociologist, media theorist, and provocateur — who pushed the critique of representation to its limit. In the 1980s, where others saw distortion, he saw substitution: signs that no longer referred to anything real. Most vividly, in his surreal, gleaming 1986 travelogue America, he described the U.S. not as a place, but as a performance — a projection without depth, still somehow running.

Where Foucault showed that knowledge was power, and Debord showed that images replaced life, Baudrillard argued that signs had broken free altogether. A map might once distort or simplify — but it still referred to something real. By the late 20th century, he argued, signs no longer pointed to anything. They pointed only to each other.

You didn’t just visit Disneyland. You visited the idea of America — manufactured, rehearsed, rendered. You didn’t just use money. You used confidence by handing over a credit card — a symbol of wealth that is lighter and moves faster than any gold.

In some ways, he was updating a much older insight by another Frenchman. When Alexis de Tocqueville visited America in the 1830s, he wasn’t just studying law or government — he was studying performance. He saw how Americans staged democracy, how rituals of voting and speech created the image of a free society even as inequality and exclusion thrived beneath it. Tocqueville wasn’t cynical. He simply understood that America believed in its own image — and that belief gave it a kind of sovereign feedback loop.

Baudrillard called this condition simulation — when representation becomes self-contained. When the distinction between real and fake no longer matters because everything is performance. Not deception — orchestration.

He mapped four stages of this logic:

Faithful representation – A sign reflects a basic reality. A map mirrors the terrain.

Perversion of reality – The sign begins to distort. Think colonial maps as logos or exclusionary zoning.

Pretending to represent – The sign no longer refers to anything but performs as if it does. Disneyland isn’t America — it’s the fantasy of America. (ironically, a car-free America)

Pure simulation – The sign has no origin or anchor. It floats. Zillow heatmaps, Uber surge zones — maps that don’t reflect the world, but determine how you move through it.

We don’t follow maps as they were once known anymore. We follow interfaces.

And not just in apps. Cities themselves are in various stages of simulation. New York still sells itself as a global center. But in a distributed globalized and digitized economy, there is no center — only the perversion of an old reality. Paris subsidizes quaint storefronts not to nourish citizens, but to preserve the perceived image of Paris. Paris pretending to be Paris. Every city has its own marketing campaign. They don’t manage infrastructure — they manage perception. The skyline is a product shot. The streetscape is marketing collateral and neighborhoods are optimized for search.

Even money plays this game.

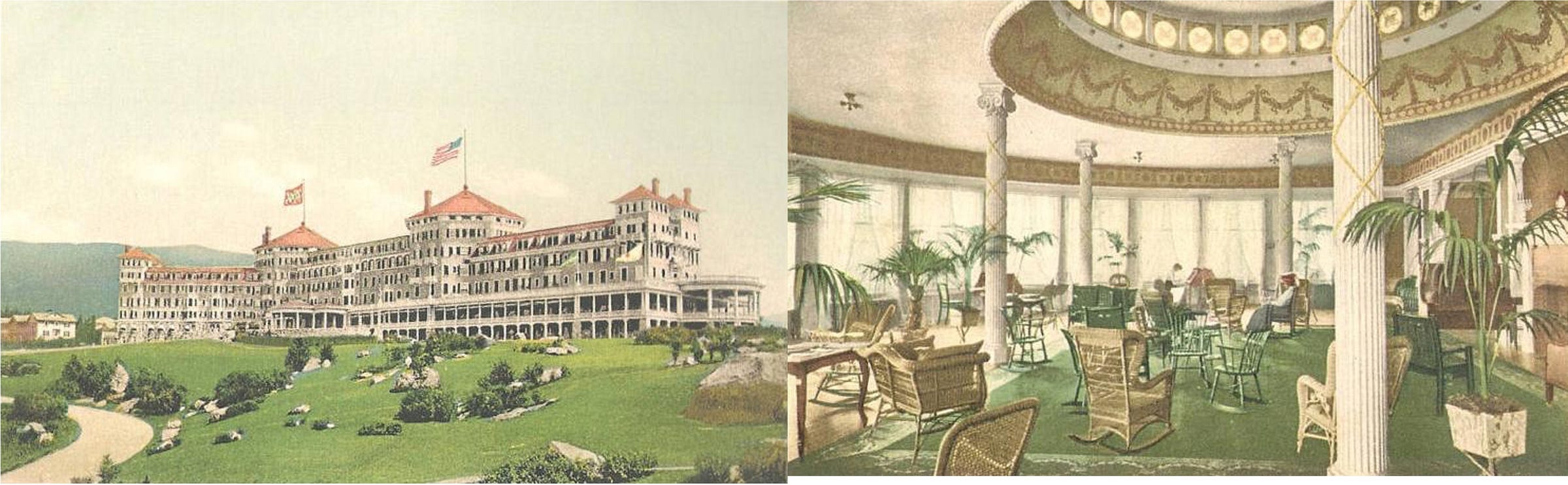

The U.S. dollar wasn’t always king. That title once belonged to the British pound — backed by empire, gold, and industry. After World War II, the dollar took over, pegged to gold under the Bretton Woods convention — a symbol of American postwar power stability…and perversion. It was forged in an opulent, exclusive, hotel in the mountains of New Hampshire. But designed in the style of Spanish Renaissance Revival, it was pretending to be in Spain.

Then in 1971, Nixon snapped the dollar’s gold tether. The ‘Nixon Shock’ allowed the dollar to float — its value now based not on metal, but on trust. It became less a store of value than a vessel of belief. A belief that is being challenged today in ways that recall the instability and fragmentation of the pre-WWII era.

And this dollar lives in servers, not Industrial Age iron vaults. It circulates as code, not coin. It underwrites markets, wars, and global finance through momentum alone. And when the pandemic hit, there was no digging into reserves.

The Federal Reserve expanded its balance sheet with keystrokes — injecting trillions into the economy through bond purchases, emergency loans, and direct payments. But at the same time, Trump 1.0 showed printing presses rolling, stacks of fresh bills bundled and boxed — a spectacle of liquidity. It was monetary policy as theater. A simulation of control, staged in spreadsheets by the Fed and photo ops by the Executive Branch. Not to reflect value, but to project it. To keep liquidity flowing and to keep the belief intact.

This is what Baudrillard meant by simulation. The sign doesn’t lie — nor does it tell the truth. It just works — as long as we accept it.

MOOD OVER MEANING

Reality is getting harder to discern. We believe it to be solid — that it imposes friction. A law has consequences. A price reflects value. A city has limits. These things made sense because they resist us. Because they are real.

But maybe that was just the story we told. Maybe it was always more mirage than mirror.

Now, the signs don’t just point to reality — they also replace it. We live in a world where the image outpaces the institution. Where the copy is smoother than the original. Where AI does the typing. Where meaning doesn’t emerge — it arrives prepackaged and pre-viral. It’s a kind of seductive deception. It’s hyperreality where performance supersedes substance. Presence and posture become authority structured in style.

Politics is not immune to this — it’s become the main attraction.

Trump’s first 100 days didn’t aim to stabilize or legislate but to signal. Deportation as UFC cage match — staged, brutal, and televised. Tariff wars as a way of branding power — chaos with a catchphrase. Climate retreat cast as perverse theater. Gender redefined and confined by executive memo. Birthright citizenship challenged while sedition pardoned. Even the Gulf of Mexico got renamed. These aren’t policies, they’re productions.

Power isn’t passing through law. It’s passing through the affect of spectacle and a feed refresh.

Baudrillard once wrote that America doesn’t govern — it narrates. Trump doesn’t manage policy, he manages mood. Like an actor. When America’s Secretary of Defense, a former TV personality, has a makeup studio installed inside the Pentagon it’s not satire. It’s just the simulation, doing what it does best: shining under the lights.

But this logic runs deeper than any single figure.

Culture no longer unfolds. It reloads. We don’t listen to the full album — we lift 10 seconds for TikTok. Music is made for algorithms. Fashion is filtered before it’s worn. Selfhood is a brand channel. Identity is something to monetize, signal, or defend — often all at once.

The economy floats too. Meme stocks. NFTs. Speculative tokens. These aren’t based in value — they’re based in velocity. Attention becomes the currency.

What matters isn’t what’s true, but what trends. In hyperreality, reference gives way to rhythm. The point isn’t to be accurate. The point is to circulate. We’re not being lied to.

We’re being engaged. And this isn’t a bug, it’s a feature.

Which through a Baudrillard lens is why America — the simulation — persists.

He saw it early. Describing strip malls, highways, slogans, themed diners he saw an America that wasn’t deep. That was its genius he saw. It was light, fast paced, and projected. Like the movies it so famously exports. It didn’t need justification — it just needed repetition.

And it’s still repeating.

Las Vegas is the cathedral of the logic of simulation — a city that no longer bothers pretending. But it’s not alone. Every city performs, every nation tries to brand itself. Every policy rollout is scored like a product launch. Reality isn’t navigated — it’s streamed.

And yet since his writing, the mood has shifted. The performance continues, but the music underneath it has changed. The techno-optimism of Baudrillard’s ‘80s an ‘90s have curdled. What once felt expansive now feels recursive and worn. It’s like a show running long after the audience has gone home. The rager has ended, but Spotify is still loudly streaming through the speakers.

“The Kids' Guide to the Internet” (1997), produced by Diamond Entertainment and starring the unnervingly wholesome Jamison family. It captures a moment of pure techno-optimism — when the Internet was new, clean, and family-approved. It’s not just a tutorial; it’s a time capsule of belief, staged before the dream turned into something else. Before the feed began to feed on us.

Trumpism thrives on this terrain. And yet the world is changing around it. Climate shocks, mass displacement, spiraling inequality — the polycrisis has a body count. Countries once anchored to American leadership are squinting hard now, trying to see if there’s anything left behind the screen. Adjusting the antenna in hopes of getting a clearer signal. From Latin America to Southeast Asia to Europe, the question grows louder: Can you trust a power that no longer refers to anything outside itself?

Maybe Baudrillard and Tocqueville are right — America doesn’t point to a deeper truth. It points to itself. Again and again and again. It is the loop. And even now, knowing this, we can’t quite stop watching. There’s a reason we keep refreshing. Keep scrolling. Keep reacting. The performance persists — not necessarily because we believe in it, but because it’s the only script still running.

And whether we’re horrified or entertained, complicit or exhausted, engaged or ghosted, hired or fired, immigrated or deported, one thing remains strangely true: we keep feeding it. That’s the strange power of simulation in an attention economy. It doesn’t need conviction. It doesn’t need conscience. It just needs attention — enough to keep the momentum alive. The simulation doesn’t care if the real breaks down. It just keeps rendering — soft, seamless, and impossible to look away from. Like a dream you didn’t choose but can’t wake up from.

REFERENCES

Barthes, R. (1972). Mythologies (A. Lavers, Trans.). Hill and Wang. (Original work published 1957)

Baudrillard, J. (1986). America (C. Turner, Trans.). Verso.

Debord, G. (1994). The Society of the Spectacle (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Zone Books. (Original work published 1967)

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Vintage Books.

Hind, S., & Gekker, A. (2019). On autopilot: Towards a flat ontology of vehicular navigation. In C. Lukinbeal et al. (Eds.), Media’s Mapping Impulse. Franz Steiner Verlag.

Linnaeus, C. (1735). Systema Naturae (1st ed.). Lugduni Batavorum.

Perkins, C. (2009). Philosophy and mapping. In R. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. Elsevier.

Raaphorst, K., Duchhart, I., & van der Knaap, W. (2017). The semiotics of landscape design communication. Landscape Research.

Roberts, L. (2008). Cinematic cartography: Movies, maps and the consumption of place. In R. Koeck & L. Roberts (Eds.), Cities in Film: Architecture, Urban Space and the Moving Image. University of Liverpool.

Tocqueville, A. de. (2003). Democracy in America (G. Lawrence, Trans., H. Mansfield & D. Winthrop, Eds.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1835)

Weber, M. (1958). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (T. Parsons, Trans.). Charles Scribner’s Sons. (Original work published 1905)