Hello Interactors,

Beneath the surface of election fatigue and endless punditry lies a deeper story — one rooted in the economic geography of this nation. It’s a tale of two Americas: the urban hubs thriving on growth and globalization, and the rural heartland struggling to hold on. One of those hubs allowed my career and family to grow and the other allowed me to grow.

The outcome of this election is well timed with Interplace’s fall theme of economic geography. Let’s step back from the noise to explore how decades of policy, technology, and shifting demographics have redrawn the map of opportunity.

This isn’t just about red versus blue — it’s about who we are, how we got here, and where we go next.

DIVIDED VOTES, DIVIDED LIVES

The 2024 presidential election highlighted many things, but one that really resonates with me is the growing urban-rural divide in American politics. Trump dominated rural voters and Harris dominated urban centers. This contrast is reminiscent of 2016, but has been building through decades of economic divergence: urban areas thrive on knowledge economies and globalization, while rural regions face stagnation and demographic decline. This enduring divide underscores the differing opportunities and values of urban and rural voters that renders as blue and red election maps.

The U.S. operates on division. It’s driven by a political and economic duopoly. Two major parties dominate, limiting ideological diversity and reducing complex issues to binary debates. This unfairly ignores the nuanced solutions needed to bridge these yawning economic and human geography gaps. Economically, we can see corporate power’s concentrated influence, with dominant industries in technology, finance, and healthcare shaping policy, market dynamics, and communities. Smaller players, including local businesses and alternative voices, are often overshadowed, ignored, or silenced.

The effects are visible in places like King County, Washington where I live. Tech giants like Microsoft and Amazon attract and fuel thriving, diverse, and mostly progressive communities. Meanwhile, in rural Adair County, Iowa, where my parents grew up and where I still have relatives, residents rely heavily on government transfers. They’re struggling to support growing aging populations and reeling from closures of vital services, including retirement homes. My own uncle faced this fate, forced into a failing trailer home to die after his Baptist church-financed retirement home was sold in 2022 to a private equity firm who promptly and callously shut it down.

These rural areas have become Republican strongholds, drawn to promises of reversing globalization, reshaping economic policies, and making their communities great again. With a 75.68% turnout of 5,423 eligible voters in Adair County, Iowa, 71.47% of them went to Trump in 2024.1 Sadly, their vulnerabilities are exploited by false narratives framing urban elites as adversaries to rural traditions and values. Though, these narratives aren’t entirely false. Both parties of our duopoly largely ignore, disregard, or patronize the realities of rural successes, strivings, and struggles — as do most urbanites.

ROOTS OF THE RURAL RIFT

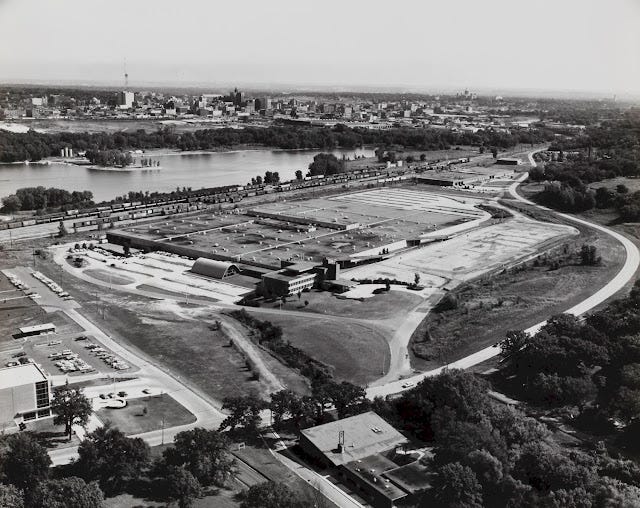

Growing up in Warren County, Iowa, in the 1970s and 1980s provided a firsthand view of some of these rural and urban transformations. Suburban to Polk County and Des Moines, Warren County was close to economic growth from finance, insurance, and some manufacturing. My father worked as a financial analyst at Massey Ferguson, while my uncle held a blue-collar factory job, representing the industrial stability of the area at the time.

My parents grew up in a far more rural Orient, Iowa, in Adair County where Massey Ferguson tractors had already been hard at work for decades. They shared stories of their little town being a vibrant agricultural hub with a bustling grain elevator next to a train track and a lively Main Street. I saw remnants of this economy as a boy, but by the time I reached high school in the 1980s, it was already in decline. That decline was punctuated on June 10, 2024, when the Orient school board voted to dissolve the school where my parents went and grandmother taught due to ongoing enrollment and financial issues.

Orient is not alone; the 1980s marked widespread economic decline across rural America. The so-called "Green Revolution," which introduced advanced agricultural technologies, prioritized efficiency through mechanization and consolidation. While it modernized farming and boosted crop yields, it also drove smaller farms out of business and accelerated rural depopulation as large agribusinesses dominated.

Adair County exemplified these changes, losing its economic backbone as family farms were replaced by larger operations, leaving Main Streets struggling. In contrast, Warren County benefited from its proximity to Des Moines' expanding economy and has become one of Iowa's fastest-growing counties in recent years. The disparity between suburban and rural areas continues to grow.

I see now how the Reagan era of the 1980s helped to hammer in the political and economic wedge of today’s divide.

Reagan’s economic agenda, focused on deregulation, tax cuts, and free-market principles, favored urban areas that were better equipped to leverage these shifts. Urban centers like Des Moines diversified into finance and insurance, while rural regions like Adair County became vulnerable to agricultural volatility and light-industry manufacturing.

This era also saw a transformation in the political alignment of what some call the ‘rural petite bourgeoisie’ — also known as ‘small business owners’ and local elites rich with real estate capital. These, overwhelmingly men, traditionally held moderate views, blending New Deal liberalism with pragmatic conservatism. Facing economic pressures from rural decline, this group turned towards Reagan’s low-tax, deregulatory policies as vital for their small businesses' survival in a challenging economy. Meanwhile, large farm and property owners benefitted from skewed farm bills sponsored by Senator Charles Grassley. “Chuck” was first elected in 1981 and is still in office. He is the longest serving member of congress at age 91.

In contrast to urban counterparts who increasingly supported redistributive policies, rural elites opposed government spending and regulations they viewed as threats to their businesses. This shift fostered a rural political identity closely linked to the Republican Party, deepening the divide as local leaders endorsed short-term beneficial policies that often worsened structural challenges in their communities.

Reagan’s emphasis on reducing government intervention also weakened the social safety net that many rural areas relied on during economic downturns. This period marked significant wealth redistribution away from struggling rural economies, as policies favored global trade and technological advancements benefiting urban industries. Free trade agreements like NAFTA, initiated under Reagan and expanded under Bill Clinton in the 90s, further destabilized rural manufacturing and agriculture.

Reagan’s rhetoric of self-reliance resonated with rural voters who saw these values reflecting their traditions. However, these policies sowed the seeds of economic decline that later led rural areas to depend on government transfers, especially as populations aged — nearly one quarter of Adair County’s residents are over 65.

Medicare and Medicaid dominate government transfers in these areas. For those in their prime, the shift towards deregulated markets and globalization has left their economies vulnerable. As the gap between urban and rural widens, questions remain about whether Trump's promise to end NAFTA will improve or worsen their circumstances.

PROSPERITY AND PRECARITY

The urban-rural economic and demographic divide was worsened by the "China Shock" of the 2000s, which laid the groundwork for Trump’s political strategy. This "China Shock" refers to the economic disruption following China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, resulting in a surge of cheap imports and offshoring of manufacturing jobs. Rural communities suffered greatly. They faced accelerated job losses and industries already weakened by NAFTA collapsed.

Trump's populist critiques of globalization and free trade, along with his promises to revive manufacturing, resonated with rural voters disillusioned by years of economic decline. His focus on preserving Social Security and Medicare appealed to the swell of aging Baby Boomer populations in rural areas, where government transfers — mostly in the form of medicare and social security — have become vital for personal income.

Trump also used immigration as a fear tactic, employing anti-Asian rhetoric to foster suspicion of China and Chinese immigrants while extending this narrative to immigrants from Mexico, and Central and South America. Many of these immigrants fled due to policies supported by Reagan in the 1980s that destabilized their regions. The Reagan administration backed authoritarian regimes and aided military interventions aimed at combating pro-social movements, which led to violence and economic hardship still roiling Central America as effects of climate change ravage.

NAFTA further worsened this situation by enabling U.S. companies to exploit workers with low wages and displacing small farmers through large agricultural projects, echoing the impacts of the “Green Revolution.” These policies, together with the effects of a changing climate, have disrupted livelihoods and forced many to migrate north for survival.

Trump shifted blame for stagnant wages and reduced opportunities in rural America onto immigrants, claiming they were “stealing” jobs. However, the true issues often stemmed from systemic exploitation and corporate priorities aimed at suppressing wages. Rural workers, predominantly White but also Black and Brown legal immigrants, faced declining opportunities due to U.S. companies’ refusal to raise wages. Instead, especially with low-wage agricultural and meat packing jobs, they hired, directly and indirectly, illegal immigrant labor.

By framing immigration and globalization as adversaries, Trump obscured the structural causes of economic distress, deepening cultural divides while rallying rural voters with a narrative of racism, grievance, and mistrust.

The story of America’s divide is not just about economic shifts or political realignments—it’s a nation grappling with what it means to belong, prosper, and endure. Beneath the surface lies a deeper truth: the urban-rural rift mirrors our struggles with identity, purpose, and interdependence.

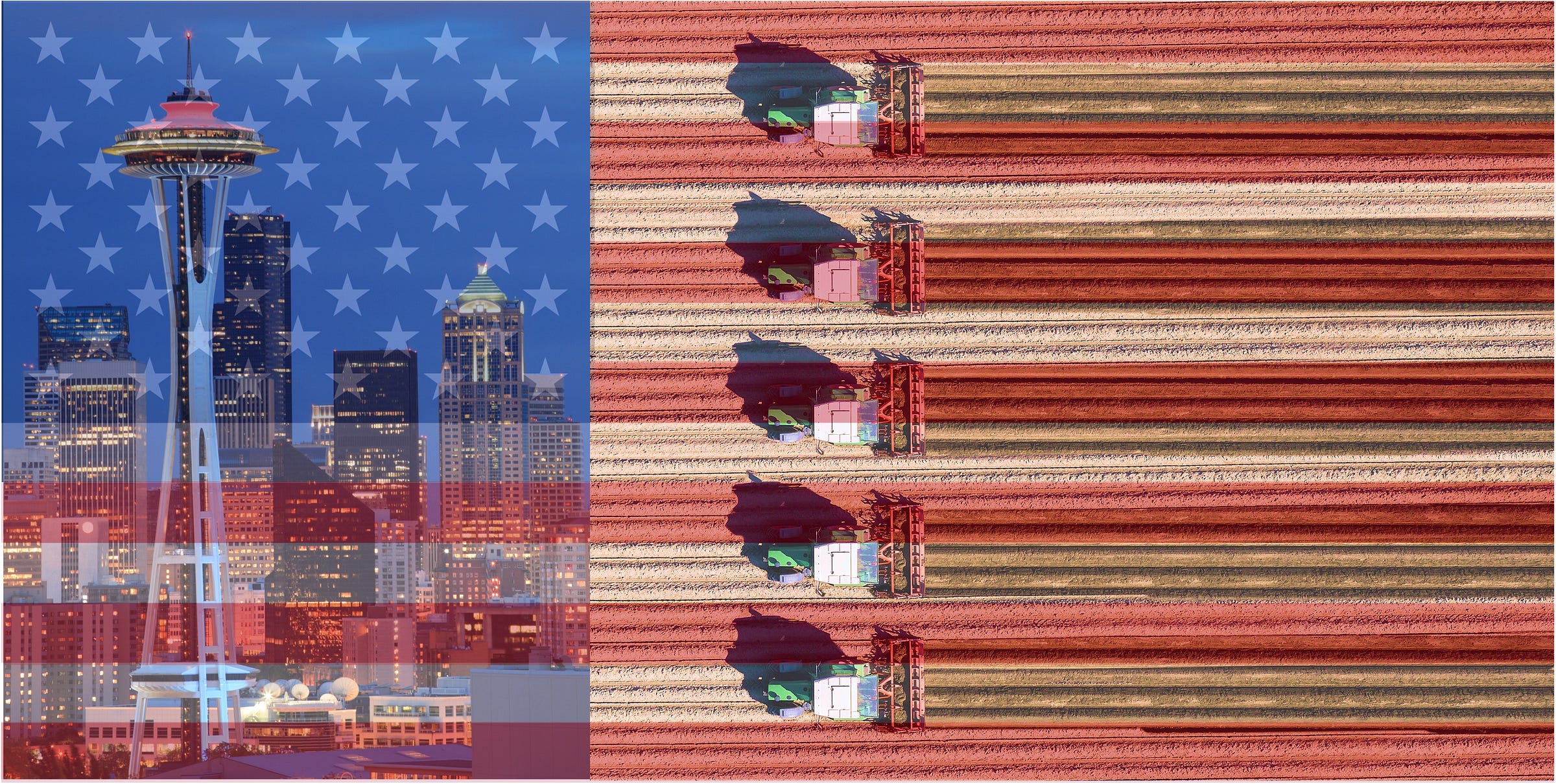

I see myself in this divide. Place profoundly shaped my life — not just through opportunities but in the values it instilled and the dreams it inspired. The urban skylines of the Seattle area, driven by innovation, look outward to a globalized future, while the rural landscapes of my childhood, rooted in tradition, look inward to preserve what they hold most dear. These differing perspectives underscore the ugly and unjust tensions and diverse and defining beauty of America’s existential, albeit bewildering, struggle.

Can we rediscover the common threads that bind us? The prosperity of the metropolis cannot endure without the resilience of Main Street, just as rural values lose meaning without the context of a connected world. Division is not our destiny — its what forces our decisions.

But the contours of our physical, human, and economic geographies, though disparate, need not dictate our future.

Like Iowa’s farmlands, where soil renews through struggle, and Seattle’s economy, thriving on adaptability, our future can grow stronger through enduring hardship and embracing a transformative, just, and inclusive tomorrow.

As of November 13, 2024. Source: Iowa Secretary of State Election Results.

References:

EIG Research. (November 2024). EIG Great Transfer-Mation: Data. GitHub. https://github.com/EIG-Research/EIG-Great-Transfer-Mation/tree/main/data

EIG Research. (November 2024). The great transfer-mation. https://eig.org/great-transfermation/