Hello Interactors,

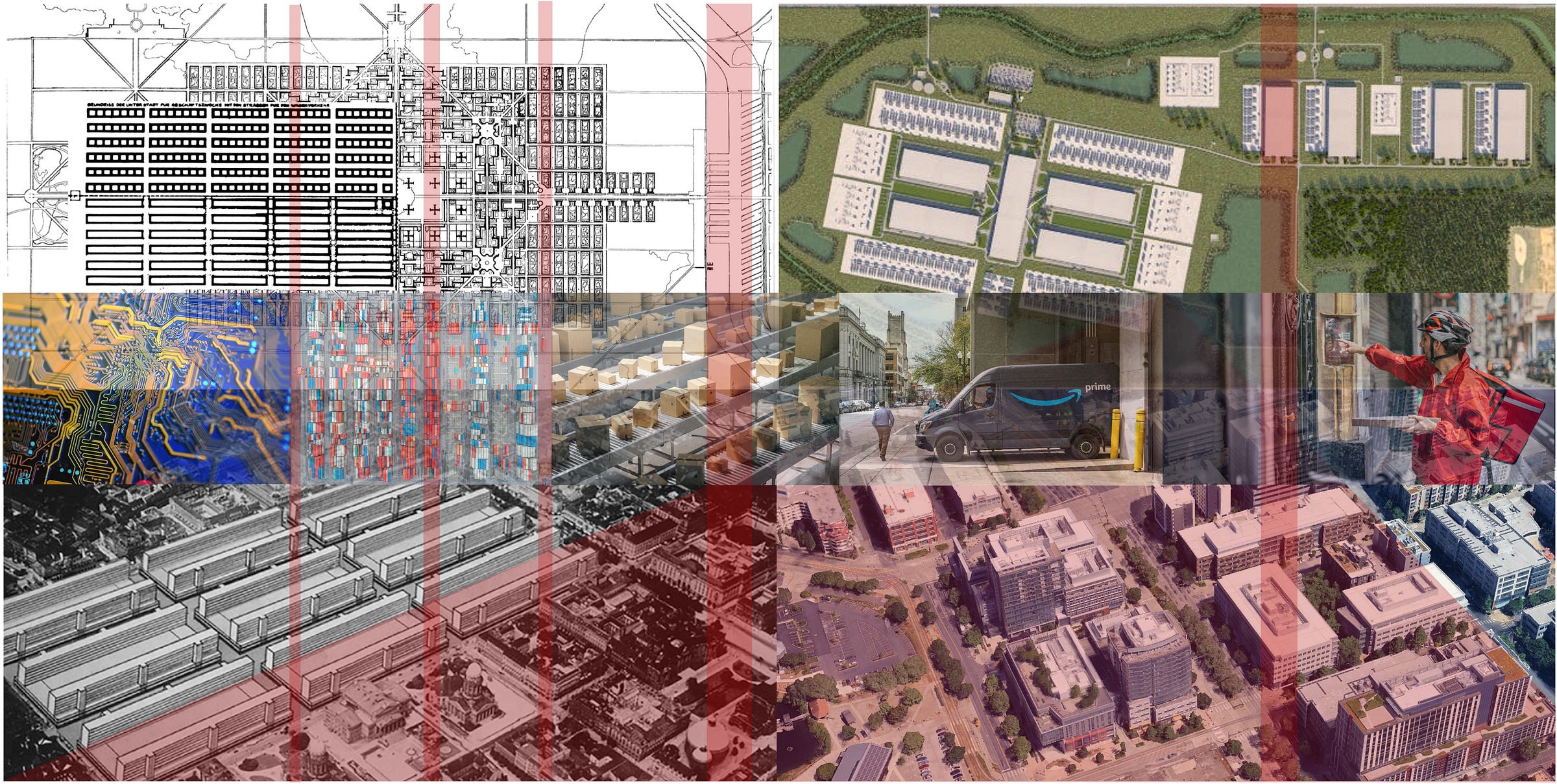

Spring at Interplace brings a shift to mapping, GIS, and urban design. While talk of industrial revival stirs nostalgia — steel mills, union jobs, bustling Main Streets — the reality on the ground is different: warehouses, data centers, vertical suburbs, and last-mile depots. Less Rosy the Riveter, more Ada Lovelace. Our cities are being shaped accordingly — optimized not for community, but for logistics.

FROM STOREFRONTS TO STEEL DOORS

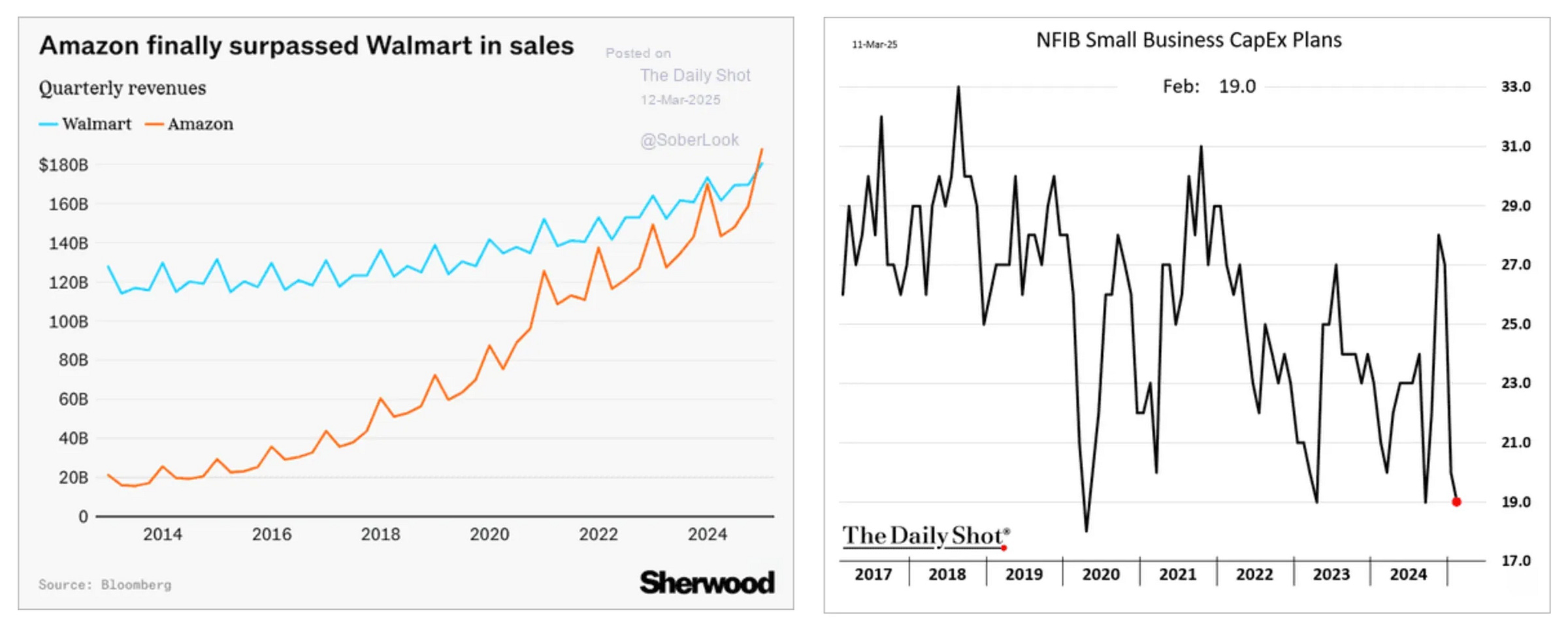

Let’s start with these two charts recently shared by the historian of global finance and power Adam Tooze at Chartbook. One shows Amazon passing Walmart in quarterly sales for the first time. The other shows a steadily declining drop in plans for small business capital expenditure. Confidence shot up upon the election of Trump, but dropped suddenly when tariff talks trumped tax tempering. Together, these charts paint a picture: control over how people buy, build, and shape space is shifting — fast.

It all starts quietly. A parking lot gets fenced off. Trucks show up. Maybe the old strip mall disappears overnight. A few months later, there’s a low, gray building with no windows. No grand opening. Just a stream of delivery vans pulling in and out.

This isn’t just a new kind of facility — it’s a new kind of urban and suburban logic.

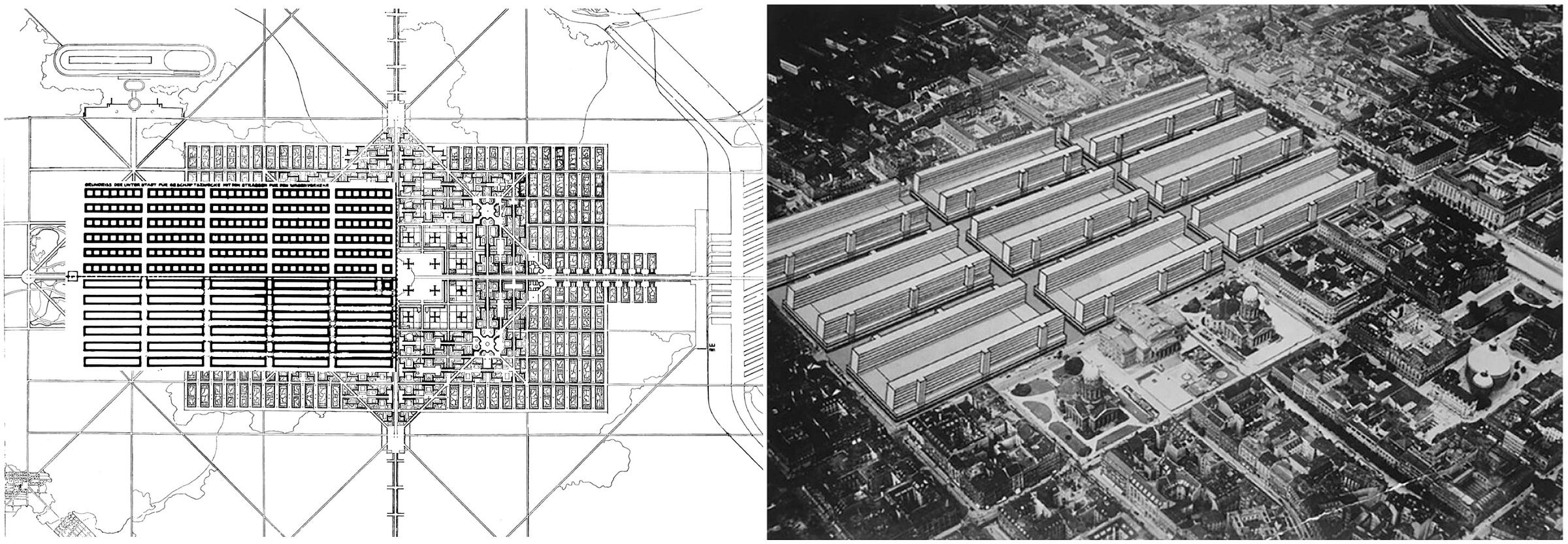

Platform logistics has rewritten the rules of space. Where cities were once shaped by factories and storefronts, now they’re shaped by fulfillment timelines, routing algorithms, and the need to move goods faster than planning commissions can meet.

In the past, small businesses were physical anchors. They invested in place. They influenced how neighborhoods looked, felt, and functioned. But when capital expenditures from local firms drop — as that second chart shows — their power to shape the block goes with it.

What fills the vacuum is logistics. And it doesn’t negotiate like the actors it replaces.

This isn’t just a retail story. It’s a story about agency — who gets to decide what a place is for. When small businesses cut back on investment, it’s not just the storefront that disappears. So does the capacity to influence a block, a street, a community. Local business owners don’t just sell goods — they co-create neighborhoods. They choose where to open, how to hire, how to design, and what kind of social space their business offers. All of that is a form of micro-planning — planning from below. France, as one example, subsidizes these co-created neighborhoods in Paris to insure they uphold the romantic image of a Parisian boulevard.

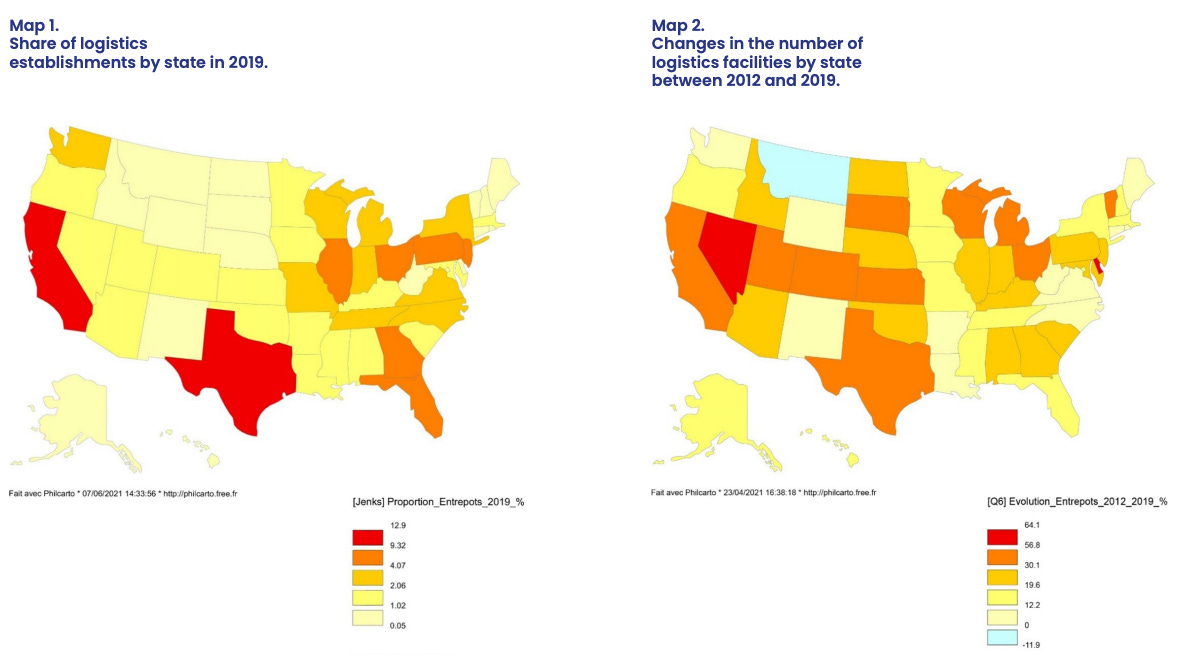

But without subsidies, these actors are disappearing. And in the vacuum, big brands and logistics move in. Not softly, either. Amazon alone added hundreds of logistics facilities to U.S. land in the past five years. Data centers compete for this land. Meta recently announced a four million square foot facility in Richland Parish, Louisiana. It will be their largest data center in the world.

These buildings are a new kind of mall. They’re massive, quiet, windowless buildings that optimize for speed, not presence. This is what researchers call logistics urbanization — a land use logic where space is valued not for what people can do in it, but for how efficiently packages and data can pass through it.1

The shift is structural. It remakes how land is zoned, how roads are used, and how people move — and it does so at a scale that outpaces most municipal planning timelines. That’s not just a market change. It’s a change in governance. Because planners? Mayors? Even state reps? They're not steering anymore. They're reacting.

City managers once had tools to shape growth — zoning, permitting, community input. But logistics and tech giants don’t negotiate like developers. They come with pre-designed footprints and expectations. If a city doesn’t offer fast approval, industrial zoning, and tax breaks, they’ll skip to the next one. And often, they won’t even say why. Economists studying these state and local business tax incentives say these serve as the “primary place-based policy in the United States.”2

It forces a kind of economic speed dating. I see it in my own area as local governments vie for the attention (and revenue) of would-be high-tech suitors. But it can be quiet, as one report suggests:

“This first stage of logistical urbanization goes largely unnoticed insofar as the construction of a warehouse in an existing industrial zone rarely raises significant political issues.”(2)

This isn’t just in major cities. Across the U.S., cities are bending their long-term plans to chase short-term fulfillment deals. Even rural local governments routinely waive design standards and sidestep public input to accommodate warehouse and tech siting — because saying no can feel like missing out on tax revenue, jobs, or political wins.(2)3

What was once a dynamic choreography of land use and local voices becomes something flatter: a data pipeline.

It isn’t all bad. Fulfillment hubs closer to homes mean fewer trucks, shorter trips, and lower emissions. Data centers crunching billions of bits is better than a PC whirring under the desk of every home. There is a scale and sustainability case to be made.

But logistic liquidity doesn’t equal optimistic livability. It doesn’t account for what’s lost when civic agency fades, or when a city works better for packages than for people. You can optimize flow — and still degrade life.

That’s what those two charts at the beginning really show. Not just an economic shift, but a spatial one. From many small decisions to a few massive ones. From storefronts and civic input to corporate site selection and zoning flips. From a lived city to a delivered one.

Which brings us to the next shape in this story — not the warehouse, but the mid-rise. Not the loading dock, but the key-fob lobby. Different function. Same logic.

HIGH-RISE, LOW TOUCH

You’ve seen them. The sleek new apartment buildings with names like The Foundry or Parc25. A yoga room, a roof deck, and an app for letting in your dog walker. “Mixed-use,” they say — but it’s mostly private use stacked vertically.

It’s much needed housing, for sure. But these aren't neighborhoods. They're private bunkers with balconies.

Yes, they’re more dense than suburban cul-de-sacs. Yes, they’re more energy-efficient than sprawl. But for all their square footage and amenity spaces, they often feel more like vertical suburbs — inward-facing, highly managed, and oddly disconnected from the street.

The ground floors are usually glazed over with placeholder retail: maybe a Starbucks, a Subway, or nothing at all…often vacant with only For Lease signs. Residents rarely linger. Packages arrive faster than neighbors can introduce themselves. There’s a gym to bench press, but no public bench or egress. You’re close to hundreds of people — and yet rarely bump into anyone you didn’t schedule.

That’s not a design flaw. That’s the point.

These buildings are part of a new typology — one that synchronizes perfectly with a platform lifestyle. Residents work remote. Order in. Socialize through screens. The architecture doesn’t foster interaction because interaction isn’t the product. Efficiency is.

Call it fulfillment housing — apartments designed to plug into an economy that favors logistics and metrics, not civic social fabrics. They’re located near tech centers, distribution hubs, and delivery corridors, and sometimes libraries or parks outdoors. What matters is access to bandwidth and smooth entry for Amazon and Door Dash.

And it’s not just what you see on the block. Behind the scenes, cities are quietly reengineering themselves to connect these structures to the digital twins — warehouses and data centers. Tucked into nearby low-tax exurbs or industrial zones, together they help reshape land use, strain energy grids, and anchor the platform economy.

They’re infrastructure for a new kind of urban life — one where presence is optional and connection to the cloud is more important than to the crowd.

Even the public spaces inside these buildings — co-working lounges, shared kitchens, “community rooms” — are behind fobs, passwords, and management policies. Sociologists have called this the anticommons: everything looks shared, but very little actually is.4 It's curated collectivity, not true community.

And it's not just isolation — it’s predictability. These developments are built to minimize risk, noise, conflict, friction. Which is also to say: they’re built to minimize surprise. The kind of surprise that once made cities exciting. The kind that made them social.

Some urban scholars describe these spaces as part of a broader “ghost urbanism” — a city where density exists without depth.5 Where interaction is optional. Where proximity is engineered, but intimacy is not. You can be surrounded by life and still feel like you're buffering.

The irony is these buildings often check every sustainability box. They’re LEED-certified. Near transit. Built up, not out. From a local emissions standpoint, they beat the ‘burbs’. But their occupant’s consumption, waste, and travel habits can create more pollution than homebody suburbanites. And from a civic standpoint — the standpoint of belonging, encounter, spontaneity — they’re often just as empty.

And so we arrive at a strange truth: a city can be efficient, dense, even walkable — and still feel ghosted. Because what we’ve optimized for isn’t connection. It’s delivery — to screens and doorsteps. What gets delivered to fulfillment housing may be frictionless, but it’s rarely fulfilling.

DRONES, DOMICILES, AND DISCONNECTION

I admit there’s a nostalgia for old-world neighborhoods as strong as nostalgia for industrial cities of the past. Neighborhoods where you may run into people at the mailbox. Asking someone in the post office line where they got their haircut. Sitting on the porch, just waitin’ on a friend. We used to talk about killing time, now we have apps to optimize it.

It’s not just because of screens. It’s also about what kinds of space we’ve built — and what kind of social activity they allow or even encourage.

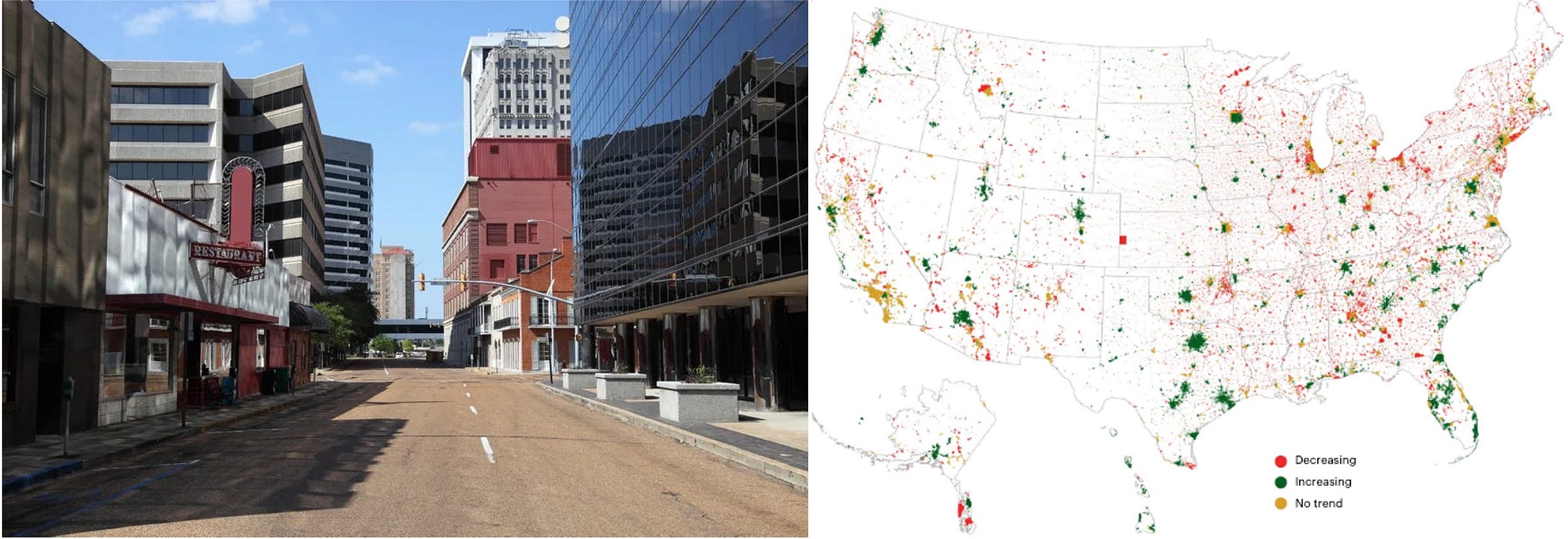

In many suburbs and edge cities, the mix of logistics zones, tech centers, and residential enclaves creates what urban theorists might call a fragmented spatial syntax. That means the city no longer “reads” as a continuous experience. Streets don’t tell stories.

There’s no rhythm from house to corner store to café to school. Instead, you get jump cuts — a warehouse here, a cul-de-sac there, a fenced-in apartment complex down the road. These are spaces that serve different logics, designed for speed, security, or seclusion — but rarely for relation. The grammar of the neighborhood breaks down. You don’t stroll. You shuttle.

You drive past a warehouse. You park in a garage. You enter through a lobby. You take an elevator to your door. There’s no in-between space — no casual friction, no civic ambiguity, no shared air.

These patterns aren’t new. But they’re becoming the norm, not the exception. You can end up living in a place but never quite arrive.

Watch most anyone under 35. Connection increasingly happens online. Friendships form in Discord servers, not diners. Parties are planned via private stories, not porch swings. You don’t run into people. You ping them.

Sometimes that online connection does spill back into the real world — meetups, pop-ups, shared hobbies that break into public space. Discord, especially, has become a kind of digital third place, often leading to real-world hangouts. It’s social. Even communal. But it’s different. Fleeting. Ephemeral. Less rooted in place, more tied to platform and notifications.

None of this is inherently bad. But it does change the role of the neighborhood as we once knew it. It’s no longer the setting for shared experience — it’s just a backdrop for bandwidth. That shift is subtle, but it adds up. Without physical places for civic life, interactions gets offloaded to platforms. Connection becomes mediated, surveilled, and datafied. You don’t meet your neighbors. You follow them. You comment on their dog through a Ring alert.

This is what some sociologists call networked individualism — where people aren’t embedded in shared place-based systems, but orbit through overlapping digital networks. And when digital is the default, the city becomes a logistics problem. Something to move through efficiently…or not. It certainly is not something we’re building together. It’s imposed upon us.

And so we arrive at a kind of paradox:

We’re more connected than ever. But we’re less entangled.

We’re more visible. But we’re less involved.

We’re living closer. But we don’t feel near.

The irony is the very platforms that hollow out public space are now where we go looking for belonging. TikTok isn’t just where we go to kill time — it’s where we go to feel seen. If your neighborhood doesn’t give you identity, the algorithm will.

Meanwhile, the built environment absorbs the logic of logistics. Warehouses and data centers at the edge. Mid-rises in the core. Streets engineered for the throughput of cars and delivery vans. Housing designed for containment. And social life increasingly routed elsewhere.

It all works. Until you want to feel something.

We’re social creatures, biologically wired for connection. Neuroscience shows that in-person social interactions regulate stress, build emotional resilience, and literally shape how our brains grow and adapt.6 It’s not just emotional. It’s neurochemical. Oxytocin, dopamine, and serotonin — the chemistry of belonging — fire most powerfully through touch, eye contact, shared space. When those rituals shrink, so does our sense of meaning and safety.

And that’s what this is really about. Historically cities weren’t just containers for life. They’re catalysts for feeling. Without shared air, shared time, and shared friction, we lose more than convenience. We lose the chance to feel something real — to be part of a place, not just a node in a network.

What started with two charts ends here: a world where local agency, social spontaneity, and even emotion itself are being restructured by platform logic. The city still stands. The buildings are there. The people are home. But the feeling of place — the buzz, the bump, the belonging — gets harder to find.

That’s the cost of efficiency without empathy. Of optimizing everything but meaning.

And that’s the city we’re building. Unless we build something else. We’ll need agency. And not just for planners or developers. For people.

That’s the work ahead. Not to reject the platform city. But to remake it — into something more livable. More legible. More ours.

Raimbault, J., & Heitz, A. (2024). Logistics Urbanization: Between Real Estate Financialization and the Rise of Logistics. HAL Archives.

Highsmith, A.R. (2024). Relocating Location Incentives: The Spatial Politics of Urban Logistics. [Working paper].

Rai, P., Savitch-Lew, A., Stein, S.M., & Lobel, N. (2023). Urban Warehouses as Good Neighbors: Findings from a New York City Case Study. NYC Environmental Justice Alliance.

Teys, M. (2024). The evolution of the anticommons: Exploring the implications of mixed-use developments on urban renewal by collective sales (Master’s thesis, University of New South Wales). Multi-Owned Properties Research Hub.

Easterling, K. (2016). Zombies and ghosts: Architecture and finance capitalism. Places Journal.

Orlandi, A., Darda, K.M., & Calvo-Merino, B. (2025). Dance Movement and Social Interaction: Methods in Cognitive Neuroscience. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Schorung, M., Lecourt, T., & Dablanc, L. (2022). Atlas of warehouse geography in the US. University Gustave Eiffel, Logistics City Research Chair. HAL Open Science.

Reitinger, L., DeWaard, J., Müller, D. B., & Müller, F. (2023). Population decline will reshape the built environment. Nature, 621, 28–33.