Hello Interactors,

So far this spring I’ve chronicled the spread of cadastral mapping across America. It was all part of Jefferson’s gridded agrarian vision. But by the middle of the 1800s immigrants started flooding in, the industrial age was taking hold, and cities were the thing to map.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

THE PREACH AND THE LEECH

"This lake was well named; it was but a scum of liquid mud, a foot or more deep, over which our boats were slid, not floated over, men wading each side without firm footing, but often sinking deep into this filthy mire, filled with bloodsuckers, which attached themselves in quantities to their legs. Three days were consumed in passing through this sinkhole of only one or two miles in length."1

Those are the words of Gurdon S. Hubbard, a fur trader from Vermont. In 1816, at age 18, he begged his parents to leave his job at a local hardware store to join a buddy on a fur trading expedition to Mackinac Island, Michigan. Two years later, in 1818, he found himself on a boat being drug through leech infested mud next the aptly named, Mud Lake – a terminating branch of the Des Plaines river. He was traversing a well known shortcut to Lake Michigan. As his men pulled blood sucking predatory leeches from their legs, he likely would have also been breathing in the odors of a pungent leek that grew along those shores. The Algonquin people called them Checagou.

By the time Hubbard found this shortcut, it had already been named Chicago Portage and had been used for over one hundred years. In 1673, French Jesuit priest Jacques Marquette joined French Canadian Louis Jolliet to map the Mississippi river. As they were paddling their way upstream on their return to the Great Lakes, they encountered a Miami tribe by the shore. The Miami tipped them off to a shortcut to Canada. Instead of paddling all the way up to Lake Superior, they told them they could hang a right at the Illinois River and head north through Lake Michigan instead.

The Illinois River becomes the Des Plaines River at what is now Joliet, Illinois. The river then opened to an estuary later dubbed Mud Lake near present day Lyons, Illinois – a suburb of Chicago. Thus began a days long slog tugging a boat made from birch logs; a portage to Lake Michigan and beyond.

Plodding their way to the mouth of the great lake on the horizon, Jolliet got to thinking about all the fur he could trade now that he knew this shortcut. After all, this portage connected two pivotal North American transportation routes – the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. In his journal he wrote,

“We could easily sail a ship to Florida…All that needs to be done is to dig a canal through but half a league of prairie from the lower end of Lake Michigan to the River of St. Louis [today’s Illinois River].”2

Jolliet and Marquette spread the word and soon many others were trading through the Chicago Portage. The first to settle was Jean Baptiste Point du Sable and his wife Kitihawa in the 1780s. Jean Baptiste was of French and African descent and Kitihawa was from the local Potawatomi tribe. They were married ceremoniously among her people in the 1770s and then, having converted to Catholicism, were married in 1788 in Cahokia, Illinois in a Catholic ceremony. They, and their two children, went on to build a successful farm and trading post in a well appointed log cabin. They are considered the founders of what we now call the city of Chicago. Jean Baptiste died the year Gurdon Hubbard and his leech bitten crew showed up in 1818.

GRID AS YOU GROW

That same year the Illinois General Assembly was formed, the young state’s first government. Hubbard settled in Chicago and eventually became a legislator. He lobbied tirelessly for supplemental funding from the Federal government to build a canal that would replace the pernicious Chicago Portage. It worked.

They broke ground with Hubbard wielding the spade, in 1836. By this time Hubbard had also started Chicago’s first stockyard and meat packing plant. He knew, just as Jolliet did over one hundred years before, that Chicago was destined to be an attractive port town; a symbol of growth and prosperity. But neither could have imagined what happened next. It’s hard to believe today.

When Hubbard broke ground on the canal, the population was around 4,000 people. Ten years later, in 1850, that number grew nearly eight-fold to 30,000 people. By 1886, around the time Hubbard was buried just north of Chicago at Graceland Cemetery, there were nearly one-million people living in Chicago. Immigrant populations were flooding the city for work, many as laborers on the canal. Land prices were skyrocketing.

“In 1832, a small lot on Clark Street sold for $100. Two years later, the same property sold for $3,000. And a year after that, it sold for $15,000. A newspaper reporter wrote, “[E]very man who owned a garden patch stood on his head, [and] imagined himself a millionaire….”3

It didn’t take long for survey crews to start gridding Chicago into tiny parcels. All spring I’ve been chronicling the spread of large-scale cadastral mapping across the country. While Jefferson’s vision of a gridded country included plats for developing cities, his primary objective was the expansion of land for agrarian purposes. After all, he was a farmer. But urban populations were starting to mushroom in the 1830s as masses of immigrants flooded the country. Especially Chicago.

Surveyors got to work dividing plats of land into skinny rectangles packed into gridded squares divided by roads and bounded by the curving shores of the Chicago River and Lake Michigan. This 1834 map shows the land surveyed in Chicago from 1830 to 1834. Enough to handle the nearly 4,000 residents and growing.

By 1850 the population was nearing 30,000 and the city needed to expand. By 1855 the population had already jumped to 80,000. That’s 10,000 people a year flooding a few square miles. You can see in the 1855 map above just how much Chicago grew. When the city was founded in the 1830s it was about 2.5 miles square. By 1863 it grew west, south, and north four to six miles in each direction. Urban sprawl started in Chicago almost as soon as it was founded.

BILLY AND ANDY RAND MCNALLY

The opening of the Chicago River canal in 1848 and the penetration of rail lines in the 1850s culminated in making Chicago a freight and logistics transportation hub. A system that birthed iconic companies like Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck & Co. By 1850 Chicago was the biggest city in the country.

The intense growth of the city coincided with increased ethnic diversity, complex urban activity, and a shifting cultural context. It called for new methods of infrastructure management, land use policy, and regulation — but also new maps. Mapping became tools not just for documenting the record, but for managing complexity, decision making, and the risk of calamity.

This 1869 map shows the various insurance schemes spread throughout the city. Among other purposes, it was used to assess fire risk. A need that became abundantly clear two years later when the Great Chicago Fire destroyed nearly three and a half square miles of the city leaving 300 people dead.

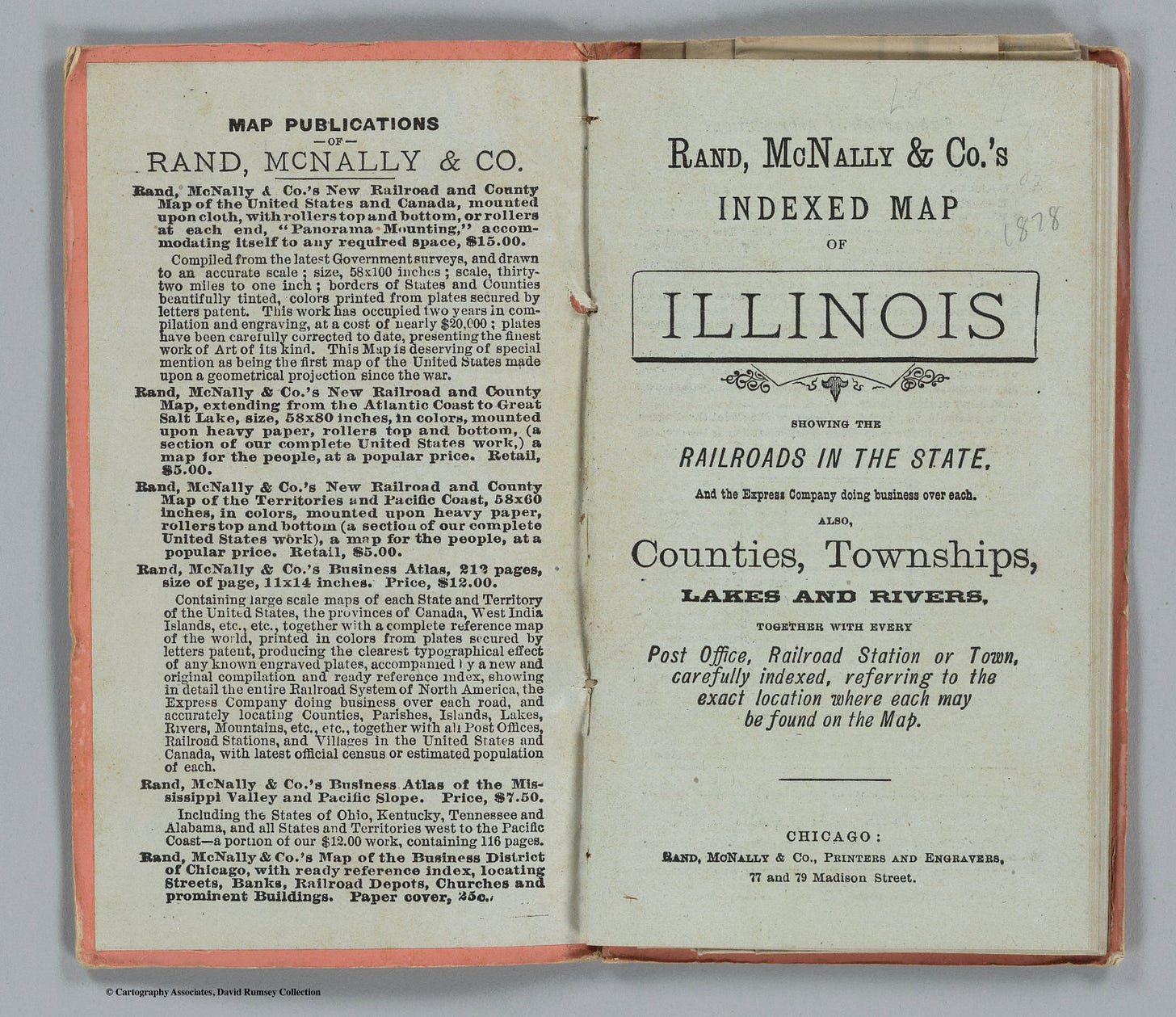

Advances in printing technology spawned new varieties of publications, including maps. A year after the Great Chicago Fire, a printmaker from Massachusetts, William Rand, and an Irish immigrant, Andrew McNally, printed their first map. Their newly formed business, Rand McNally & Co., started off printing train tickets and schedules for the dizzying strands of trains snaking through the city. Soon Rand McNally became synonymous with ‘map’ in the United States becoming the country’s most dominant mapping company.

ANOTHER SUPER HERO FROM IOWA

By 1870 48 percent of Chicago residents were immigrants; more than any other city in the country. All this urban activity brought prosperity to a rising privileged social elite, but it also brought poverty, destitution, and segregation to the disadvantaged.

Last week I talked about the 1890 U.S. census. It was the birth of American ‘Big Data’ tabulated with newly invented punch cards. America’s ‘father of mapmaking’, Henry Gannett, was tasked with charting and mapping the data. It was an impressive feat, that included new methods of modeling and visualizing the growing ethnicities in America. But the analysis included overtones of patriarchy and racist theories. Five years later, out of the slums of Chicago, emerged a more thoughtful, altruistic, yet critical counter maps.

In 1895 an all-women boarding house, called the Hull House, went about collecting, analyzing, and mapping socio-demographic data aimed at improving the lives of their immigrant neighbors. One of those women was from my home state of Iowa. Her name is Agnes Sinclair Holbrook. She was born in Marengo, Iowa in 1867 and went on to study at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. She studied math, science, and literature earning a bachelor of science degree in 1892. She then moved to Chicago to live with other women like her in the Hull House.

This was a home to women with university degrees situated in a poor Chicago neighborhood. The Hull House mission, which came from one of the founders, Jane Addams, was to empower educated women through her “Three R’s”: Residence, Research, and Reform. Instead of distantly studying anonymously surveyed data she encouraged,

“close cooperation with the neighborhood people, scientific study of the causes of poverty and dependence, communication of these facts to the public, and persistent pressure for [legislative and social] reform..."4

Young Agnes Sinclair Holbrook collected and analyzed local data from her resident immigrant community and visualized it on a map. Her intent was to inform and influence local policy but to also lift up, empower, and encourage immigrant women to seek their own opportunities. Below is an example of her work from the 1895 Hull House publication.

Digitally produced urban maps like Holbrook’s are common place today. We’re practically numbed by their presence as they bob in the rivers of social media feeds. You can bet Agnes Sinclair Holbrook would have thousands of followers if she were alive today. She’d probably also be disappointed in the progress made toward social justice.

Holbrook wasn’t a fan of sterile, dispassionate pronouncements. She believed simply stating the facts doesn’t get traction, if you want to make change it must come with the right action. As Holbrook writes in the 1895 publication of Hull-House Maps and Papers,

“Merely to state symptoms and go no farther would be idle; but to state symptoms in order to ascertain the nature of disease, and apply, it may be, its cure, is not only scientific, but in the highest sense humanitarian.”

She didn’t stop there. She had a bigger message for America’s powerful, white, male elite. It’s a message that is so relevant today, that we’d be wise to reflect and learn from the socio-political environment of the late 1800s. Here the 28 year old Holbrook states,

“The politicians work on the people's feelings, incite them against the men of the other party as their most bitter enemies; and if this doesn't succeed, they go to work deliberately to buy some. Thus adding insult to injury, they go off and set up a Pharisaic cry about the ignorance and corruption of the foreign voters.

As everything in the old country has its price, it is not at all surprising that the foreigners believe such to be the case in this also. But Americans are to blame for this; for the better class of citizens, the men who preach so much about corruption in political life, and advocate reforms, never come near these foreign voters. They do not take pains to become acquainted with these recruits to American citizenship; they never come to their political clubs and learn to know them personally; they simply draw their estimates from the most untrustworthy source, the newspapers, and then mercilessly condemn as hopeless.”5

As Holbrook and the women of Hull House worked to better improve the lives of those in the city, the ‘better class of citizens’ were leaving it. Since the 1850s streetcar suburbs were popping up everywhere to whisk affluent commuters in and out of the city; including one of America’s first planned communities, Riverside, Illinois. It was designed by famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead and it provided the bucolic utopia that continues to lure Americans from dense urban cities to this day.

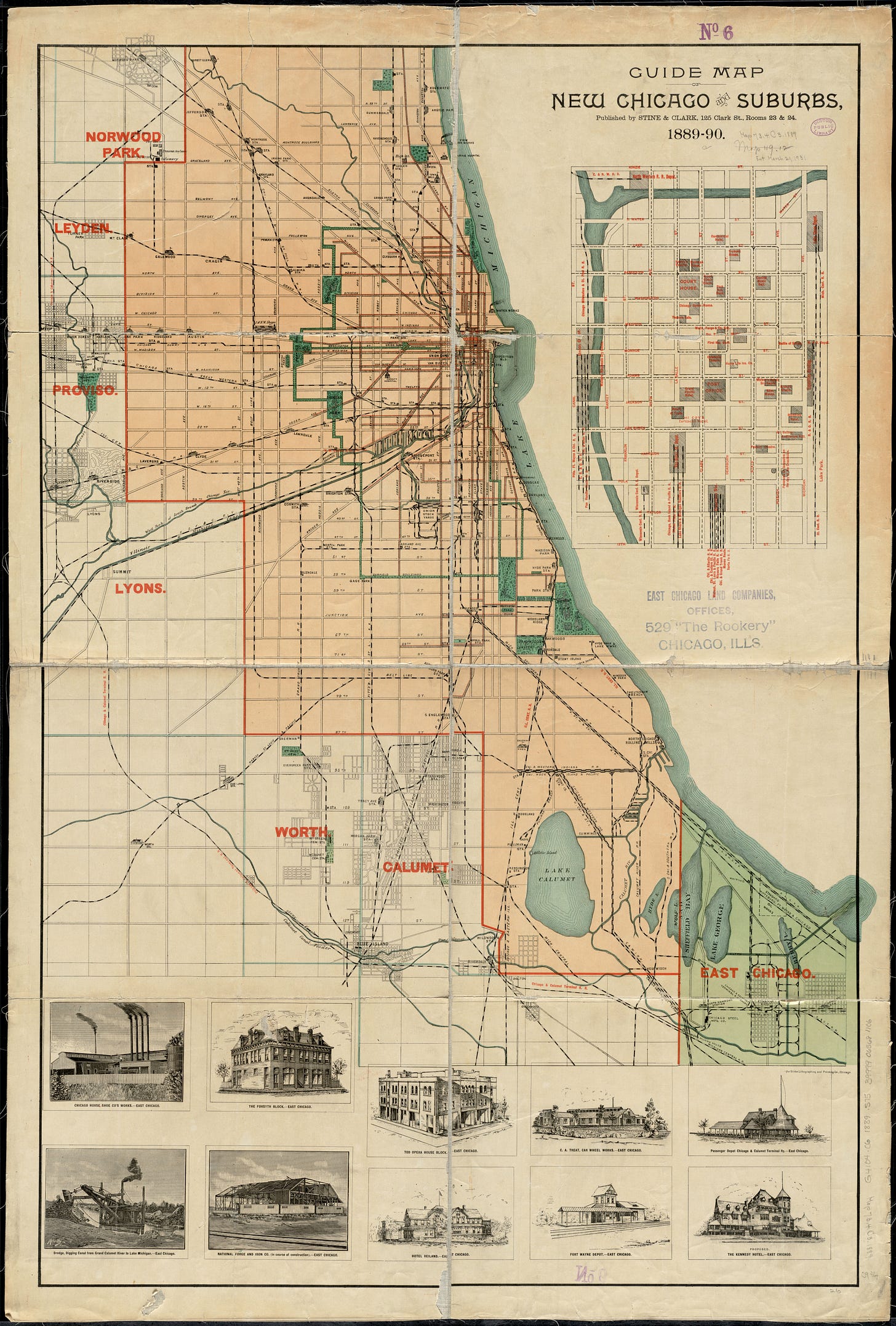

By 1873 Chicago had 11 different privately operated streetcar lines serving over 100 communities. Streetcar lines continued to stretch further distances all the way up to the twentieth century when the automobile arrived. This 1889 map shows the extent to which these suburbs dotted the surrounding landscape of Chicago.

Many believe the proliferation of roadways and automobiles created suburban sprawl in Chicago and cities like it. But it was the streetcar suburbs of the 1800s — all crafted by real estate developers looking to cash in on opportunistic land grabs. The roads of Chicago present connect the nodes of Chicago’s past.

As you can see on the map, one of those suburban communities is named Lyons. Remember Lyons? That’s where Jolliet and Marquette tugged their canoe through the slough. Then came Mr. Hubbard and the leeches too. Being the parasitic predators they are, they latch on to whatever life they encounter and forcefully, selfishly drain the life from unsuspecting victims. Showing a lack of mercy, they inject an anti-clotting chemical into the victim to prevent them from forging a natural occurring defense. And for every leech you manage to dislodge and dispatch, another appears. Waves of leeches will consume a host leaving only the leeches.

As waves of European colonial expansionists and empire builders leeched the lifeblood from unsuspecting Indigenous humans and dignity seeking dreamers they polluted the environment with their oozing industrial excrement. And so as to not wallow in their own toxic waste, they crawled over the masses calling for help, and hopped on a streetcar in search of a pristine, natural, patch of prairie next to a meandering river or lake bordered by the plant the locals called Checagou.

Share this post