Hello Interactors,

On October 12th, the United States observed Indigenous Peoples' Day, a recognition first proposed in 1977 during a UN conference in Geneva. Indigenous delegates called

“to observe October 12, the day of so-called ‘discovery’ of America, as an international day of solidarity with the indigenous peoples of the Americas”1

drawing attention to the broken treaties between Indigenous nations and the U.S. government. Thirty years later, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples affirmed that these treaties are of international concern, though the United States and a few other countries initially refused to endorse the declaration, and the resolution remains non-binding.

On Indigenous People’s Day, the satirical news outlet, The Onion, used the occasion to post a story with this headline:

“Nation’s Indigenous People Confirm They Don’t Need Special Holiday, Just Large Swaths Of Land Returned Immediately”

Today, there are 574 recognized Indigenous nations within the U.S., many of which still struggle for recognition and rights. As trade agreements like NAFTA dominate discussions on labor, immigration, and environmental impact, little attention is paid to the intricate trade systems Indigenous nations developed long before European contact. Here in the Pacific Northwest, societies like the Coast Salish had sophisticated economies driven by geographic access to key resources, especially salmon. Their control over rich fishing sites shaped trade, reinforced social hierarchies, and created territorial dynamics that predated modern trade systems.

Yet, colonization disrupted these Indigenous networks, imposing disorienting and often exploitative systems of land ownership and resource extraction. This week, I hope to explore how the adaptive strategies of Indigenous nations—despite the hardships imposed by colonization—can inspire decentralized solutions to today’s environmental and socio-economic challenges, just as these nations did for millennia.

COASTAL CONTROL AND CULTURAL COMPLEXITY

The Pacific Northwest is one of the most ecologically diverse regions in North America. It was this natural abundance that enabled the Coast Salish peoples to establish rich, complex societies. Unlike the simplistic and often nomadic image of hunter-gatherers, the Coast Salish exhibited a diversity of approaches to resource management that reflect an intimate knowledge of their environment.

According to Colin Grier, an anthropologist and archaeologist known for his research on Indigenous societies of the Pacific Northwest, there are expanded and diverse notions of hunter-gatherer strategies. His research demonstrates how the Coast Salish were able to create surplus production, social hierarchies, and sophisticated trade networks due to their advanced understanding of the ecological systems they lived within.

At the heart of Coast Salish society was the salmon fishery, a resource so abundant and predictable that it allowed for the development of semi-sedentary communities. Grier emphasizes that their use of ecological niche construction — such as the creation of clam gardens and fish weirs — enabled the Coast Salish to actively shape their environment to increase resource availability.

These inventions and engineered environmental modifications were essential for producing the surpluses that underpinned the region’s complex social and economic systems. Unlike the traditional view of hunter-gatherers as passive foragers, the Coast Salish were active managers of their environment, designing and building a system that could support a large population through environmental and economically sustainable practices.

The abundance of salmon, clams, and other marine resources also enabled the Coast Salish to develop highly stratified societies. Social hierarchies were reinforced by cultural practices such as the potlatch, where surplus wealth was redistributed by elites in ceremonial gatherings that solidified their social status. As Grier points out, the ability to control key resource sites — such as salmon fishing locations — allowed some families to accumulate wealth and power. This led to a clear division between elites, commoners, and slaves.

The behavioral ecology of the Coast Salish extended far beyond simple resource extraction, encompassing complex social and economic strategies that allowed them to thrive in a resource-rich environment. Through kinship-based alliances and trade networks, coastal tribes maintained social cohesion and managed environmental variability, including managing large swaths of inland crops. These resources gave coastal tribes a significant advantage over inland freshwater groups, leading to unequal trade exchanges and the subjugation of inland tribes.

This dynamic of resource exploitation created internal socio-economic imbalances, as coastal elites reinforced their power and prestige through their dominance over resource-poor inland tribes. While this form of resource-based exploitation was characteristic of the Coast Salish, it foreshadowed the more rigid and racialized systems of chattel slavery that would later be imposed through European colonization, where individuals were commodified as property and permanently stripped of their freedom and rights.

SETTLER SYSTEMS AND STOLEN SOVEREIGNTY

The arrival of European settlers in the Pacific Northwest, beginning in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, marked the beginning of a profound transformation in the social, economic, and environmental landscape of the region. As Cole Harris, a renowned historical geographer, details in his book The Resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on Colonialism and Geographical Change, European colonization imposed new systems of land ownership and resource extraction that displaced Indigenous peoples and fundamentally altered their relationship with the land.

Harris's work focuses on how colonial forces reshaped the geography and socio-economic structures of Indigenous communities, leading to the dispossession of their traditional territories and resources. Harris’s analysis of the colonization of British Columbia reveals how Indigenous resource management systems, which had been developed over millennia, were systematically dismantled and replaced by European notions of private property and capitalist resource exploitation.

The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest, including the Coast Salish, relied on communal access to resources, particularly salmon fishing grounds. Control over these resources was a crucial element of their social and political organization. However, as European settlers arrived, they imposed new territorial boundaries and claimed ownership over key resource areas, such as rivers and forests. The imposition of colonial land policies eroded Indigenous control over their traditional territories, leading to the displacement of Indigenous peoples from the most productive fishing sites and hunting grounds.

Harris’s work highlights the environmental degradation that came with European settlement. The introduction of intensive logging, fishing, and agricultural practices by settlers led to the over-exploitation of resources that had once been sustainably managed by Indigenous societies. Salmon populations, which had been the lifeblood of Coast Salish society, were drastically reduced by the construction of dams and the depletion of spawning habitats. The environmental changes wrought by European settlers not only disrupted the ecological balance of the region but also undermined the socio-economic systems that had sustained Indigenous peoples for generations.

The loss of control over their lands and resources had profound social consequences for the Coast Salish and other Indigenous groups. As Harris notes, the colonial imposition of new economic systems — rooted in the extraction of natural resources for profit — displaced Indigenous peoples from their traditional economies and marginalized them within the emerging capitalist order. This dispossession of Indigenous lands and the environmental destruction that accompanied European settlement prophesied the global dynamics of resource exploitation that would come to define modern systems of trade and capitalism.

GLOBAL GREED AND GEOGRAPHIC GRAB

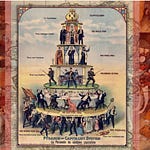

The dynamics of resource control and dispossession seen during European colonization are reflected in today’s global economic systems. World-Systems Theory, developed by Immanuel Wallerstein, a prominent sociologist and economic historian, explains how wealthier core nations dominate peripheral regions by extracting their resources and labor. This global division of labor, where core nations exploit the natural resources and workforce of less developed regions, perpetuates global inequalities—a system rooted in colonial practices and still evident today.

Trade agreements like NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) highlight these core-periphery dynamics. NAFTA, implemented in 1994, aimed to increase trade between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico by reducing tariffs and promoting economic growth. However, the benefits were unevenly distributed, with the U.S. and Canada, as core nations, reaping most of the profits, while Mexico, a peripheral nation, became vulnerable to economic and environmental exploitation. This mirrors the power imbalances between coastal and inland Indigenous tribes, where coastal elites controlled key resources and exerted dominance over less powerful inland groups.

NAFTA’s impact on Mexico’s agricultural sector illustrates this exploitation. Industrial agriculture, particularly in crops like corn and avocados for export, expanded under NAFTA. U.S. and Canadian corporations capitalized on Mexico’s cheap labor and weak environmental regulations, resulting in significant environmental degradation. This includes soil depletion, overuse of water, deforestation, and pollution from pesticides and fertilizers. Large-scale farming operations prioritize profit over sustainability, depleting natural resources and harming local ecosystems.

The environmental damage is compounded by severe social consequences. Small-scale Mexican farmers struggle to compete with the rise of large agribusinesses, leading to widespread displacement. Many are forced to abandon their land and migrate to urban areas or across the U.S. border in search of work. This displacement mirrors the historical marginalization of Indigenous peoples during European colonization, where resource loss left communities economically vulnerable and socially marginalized.

NAFTA’s exploitation of Mexico exemplifies the core-periphery dynamics described by Wallerstein. Core nations extract resources and labor from peripheral regions, reinforcing global inequalities. Mexico, economically marginalized within the global system, provides cheap labor and raw materials to wealthier nations while bearing the brunt of environmental and social costs.

Much like Indigenous peoples displaced by European settlers, Mexico remains trapped in a global system of resource extraction and dependency, a legacy of exploitation that continues to shape the world today.

The story of the Coast Salish and other Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest reminds us of how deeply we can connect to the land, each other, and the resources that sustain us. For millennia, these societies thrived by adapting to their surroundings, developing diverse ways to live in balance with the environment. Their ability to nurture the land and build lasting communities offers important lessons for the challenges we face today.

As we confront climate change, inequality, and environmental collapse, these ancient strategies of cooperation and sustainability offer perspective. The Coast Salish thrived by embracing diversity—in localized resource management, relationship-based trade, and communities rooted in reciprocity. They show us it’s possible to prosper without exploiting the earth or one another.

Though exploitation existed in these societies, its legacy continues today. Resource monopolies and social hierarchies remain short-sighted responses to complex issues, with global profit-seeking leaving behind destruction — exhausted soils, polluted waters, and displaced people.

Still, there is hope. Indigenous strategies — focused on coexistence and sustainability—prove that a different path is possible. We need to stop seeing the earth as something to conquer and start caring for it, as these early societies did. Their adaptability and long-term focus on communal survival offer valuable lessons.

The core message is simple: survival is about finding balance — between people, communities, and the earth. By learning from these Indigenous societies, we can build a future that’s not just sustainable but flourishing, where diversity is our strength and guide forward.

International Non-Governmental Organizations Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations. (1977). Archives: The final resolution. Retrieved from https://ipdpowwow.org/Archives_1.html

Ames, K. M., & Maschner, H. D. G. (1999). Peoples of the Northwest Coast: Their archaeology and prehistory. Thames & Hudson.

Boyd, R. (1999). The coming of the spirit of pestilence: Introduced infectious diseases and population decline among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774-1874. UBC Press.

Frank, A. G. (1966). The development of underdevelopment. Monthly Review Press.

Gibson, J. R. (1992). Otter skins, Boston ships, and China goods: The maritime fur trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785-1841. McGill-Queen's University Press.

Grier, C. (2016). The diversity of hunter-gatherer pasts. In B. Codding & K. Kramer (Eds.), The diversity of hunter-gatherer pasts (pp. 16-36). University of New Mexico Press.

Harris, C. (1997). The resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on colonialism and geographical change. UBC Press.

Harvey, D. (2006). The limits to capital (2nd ed.). Verso.

Matson, R. G. (1992). The origins of Northwest Coast culture. University of British Columbia Press.

Suttles, W. (1987). Coast Salish essays. Talonbooks.

Trosper, R. L. (2009). Resilience, reciprocity, and ecological economics: Northwest Coast sustainability. Routledge.

Wallerstein, I. (1974). The modern world-system I: Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. Academic Press.

Opening music: Raven Strut (feat. K.Clevenger) (DASH Remix). DKD Dancers & Dash feat. K.Clevenger.