Hello Interactors,

It’s March Madness time in the states — baskets and brackets. I admit I'd grown a bit skeptical of how basketball evolved since my playing days. As it happens, I played against Caitlin Clark’s dad, from nearby Indianola, Iowa! Unlike the more dynamic Brent Clark, I was a small-town six-foot center, taught never to face the basket and dribble. After all, it was Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s era of back-to-the-hoop skyhooks.

By college, however, I was playing pickup games in California, expected to handle the ball, shoot, dish, or drive. Just like Caitlin! The players around me were from East LA, not Indianola. Jordan was king, and basketball wasn't just evolving — it was about to explode. It’s geographic expansion and spatial dynamism has influenced how the game is played and I now know why I can’t get enough of it.

BOARDS, BOUNDARIES, AND BREAKING FREE

There was one gym in my hometown, Norwalk, Iowa, where I could dunk a basketball. The court was so cramped, there was a wall right behind the backboard. It was padded to ease post layup collisions! But when I timed it right, I could run and jump off the wall launching myself into the air and just high enough to dunk.

This old gym, a WPA project, was built in 1936 and was considered large at the time relative to population. It felt tiny by the time I played there during PE as a kid and on weekend pickup games as a teen — though it was still bigger than anything my parents experienced in rural Southern Iowa.

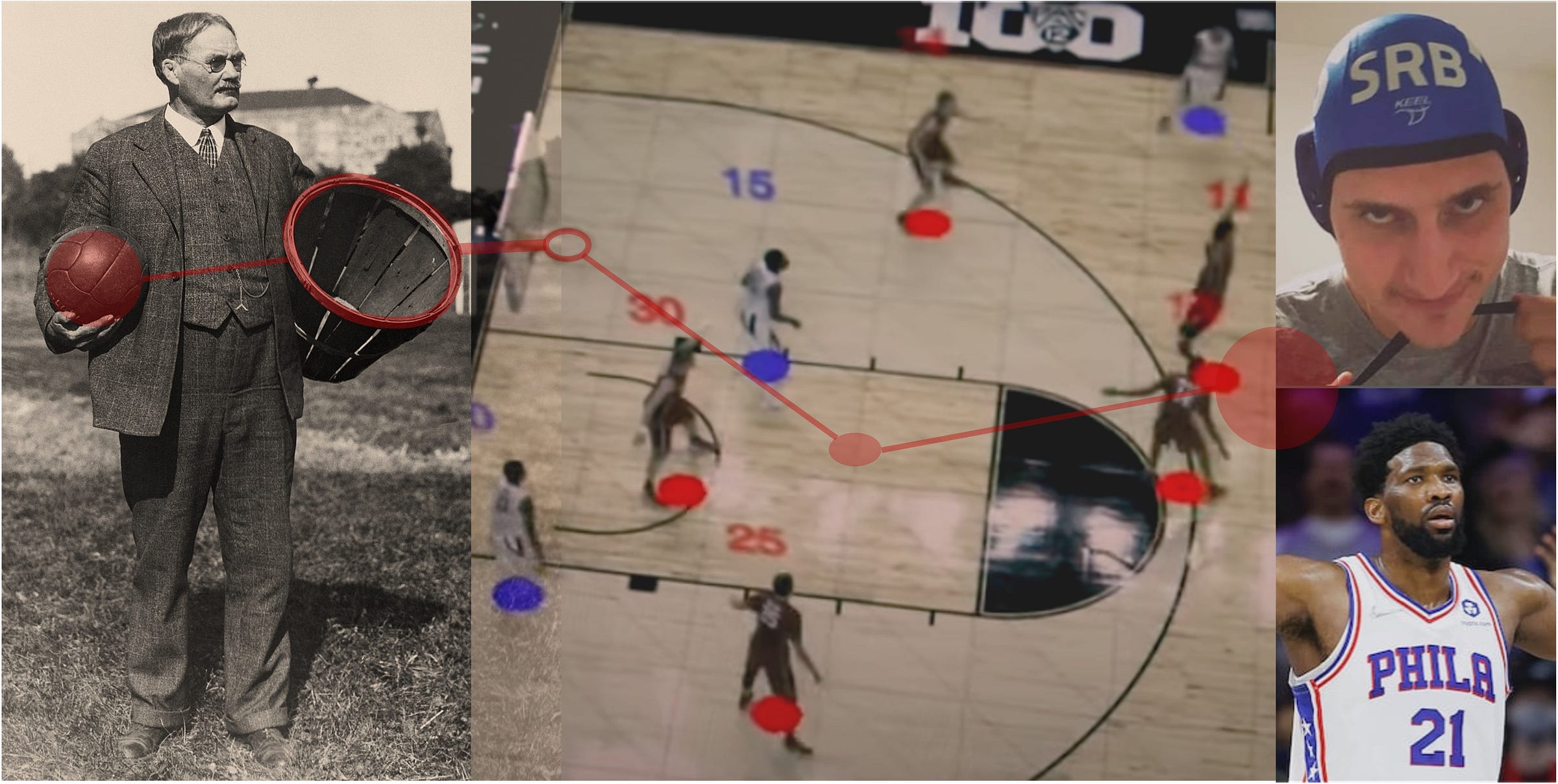

Basketball began as a sport of spatial limitation. James Naismith invented the game in 1891 — 45 years prior to my dunk gym’s grand opening. The game was invented to be played in a YMCA gym in Springfield, Massachusetts. This building dictated the court's dimensions, movement, and strategy.

Naismith’s original 13 rules emphasized order—no dribbling or running, only passing to move the ball. Early basketball wasn’t about individual drives but about constant movement within a network of passing lanes, with players anticipating and reacting in real time.

The original peach baskets were hung ten feet high on a balcony railing, with no backboards to guide shots. Misses bounced unpredictably, adding a vertical challenge and forcing players to think strategically about rebounding. Since the baskets had bottoms, play stopped after every score, giving teams time to reset and rethink.

Soon the bottom of the basket was removed, and a backboard was introduced — originally intended to prevent interference from spectators batting opponents shots from the balcony. The backboard fundamentally altered the physics of play. Now a player could more predictably bank shots of the backboard and invent new rebounding strategies.

When running while dribbling was introduced in the late 1890s, basketball’s rigid spatial structure loosened. No longer confined to static passing formations, the game became a fluid system of movement. These innovations transformed the court into an interactive spatial environment, where angles, trajectories, and rebounds became key tactical elements.

According to one theory of spatial reformulation through human behavior, structured spaces like basketball courts evolved not solely through top-down design, but through emergent patterns of use, where movement, interaction, and adaptation shape the space over time.

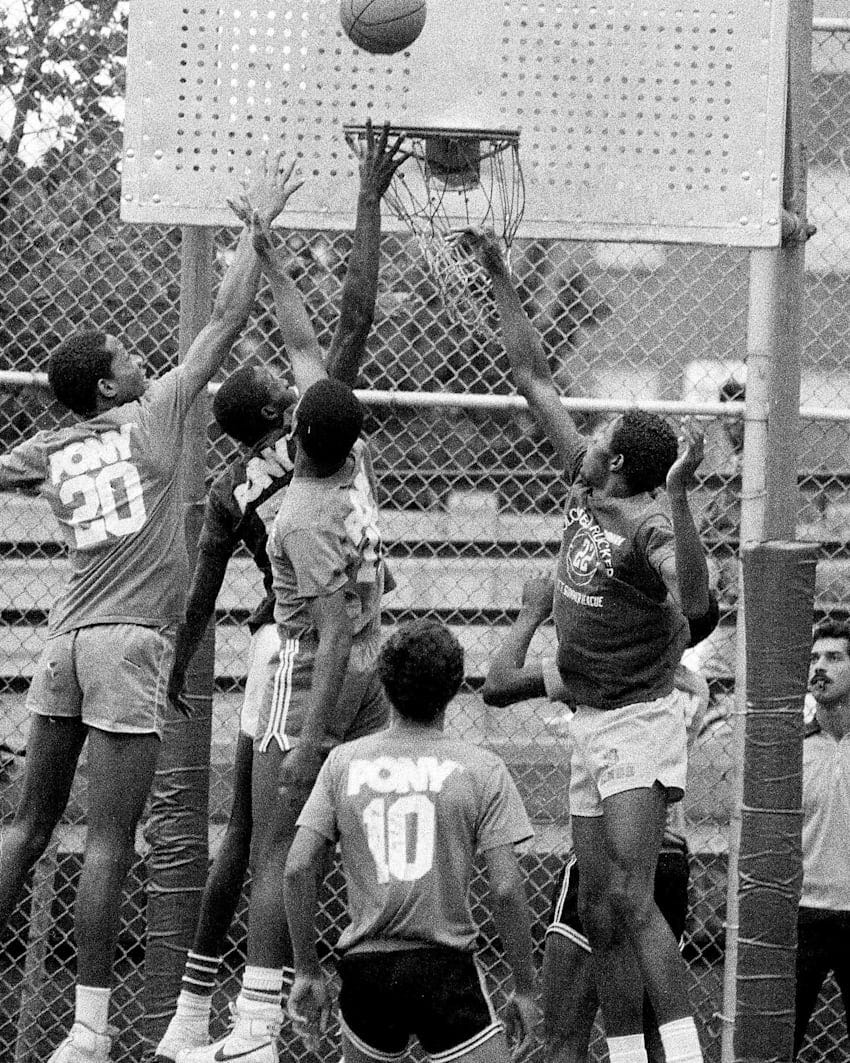

By the 1920s, the court itself expanded—not so much in physical size but in meaning. The game had spread beyond enclosed gymnasiums to urban playgrounds, colleges, and professional teams. Each expansion further evolved basketball’s spatial logic. Courts in New York’s streetball culture fostered a tight and improvisational style. Players developed elite dribbling skills and isolation plays to navigate crowded urban courts.

Meanwhile, Midwestern colleges, like Kansas where Naismith later coached, prioritized structured passing and zone defenses, reflecting the systemic, collective ethos of the game’s inventor. This period reflects microcosms of larger social and spatial behaviors. Basketball, shaped by its environment and the players who occupied it, mirrored the broader urbanization process. This set the stage for basketball’s transformation and expansion from national leagues to a truly global game.

The evolution of basketball, like the natural, constructed, and cultural landscapes surrounding it, was not static. Basketball was manifested through and embedded in cultural geography, where places evolve over time, accumulating layers of meaning and adaptation. The basketball court was no exception. The game burst forth, breaking boundaries. It branched into local leagues, between bustling cities, across regions, and globetrotted around the world.

TACTICS, TALENT, AND TRANSNATIONAL TIES

The year my ego-dunk gym was built, basketball debuted in the 1936 Olympics. That introduced the sport to the world. International play revealed contrasting styles, but it wasn’t until the 1990s and 2000s that basketball became a truly global game — shaped as much by European and African players as by American traditions.

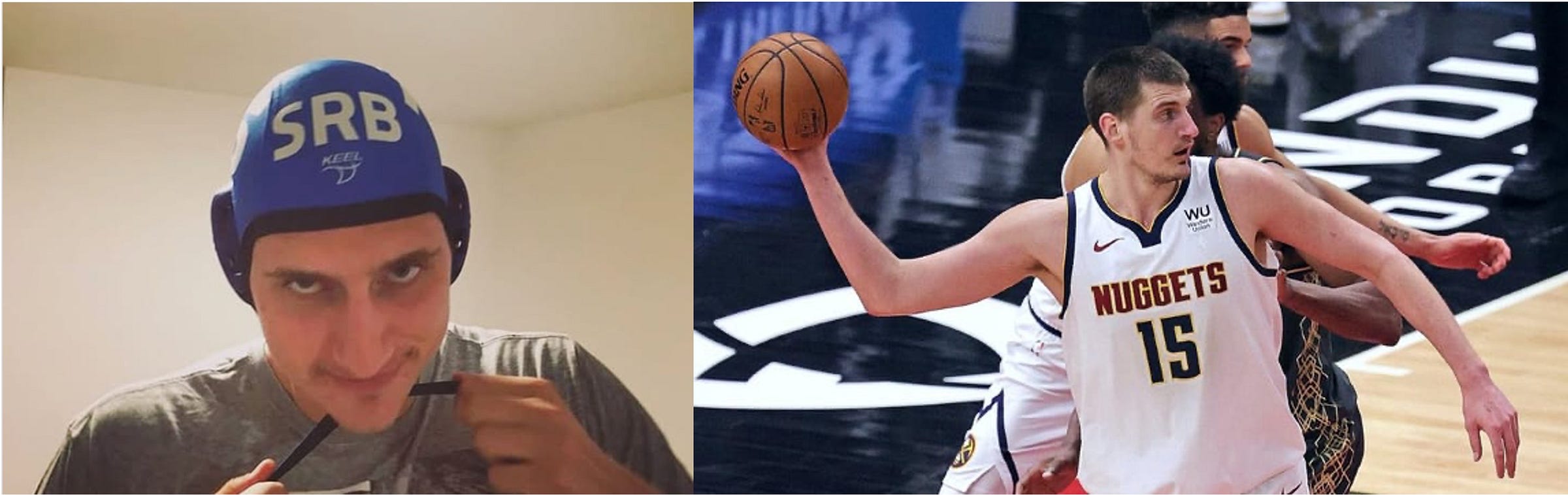

Europe’s game focused on tactical structures and spatial awareness. In the U.S., basketball was built within a high school and college system, but European basketball mimicked their club-based soccer academy model. It still does. In countries like Serbia, Spain, and Lithuania, players are taught the game from a tactical perspective first — learning how to read defenses, move without the ball, and make the extra pass. European training emphasizes court vision, spacing, and passing precision, fostering playmakers wise to the spatial dynamics of the game.

Geography also plays a role in the development of European basketball. Countries like Serbia and Lithuania, which have a strong history of basketball but relatively smaller populations, could not rely on the sheer athletic depth of players like the U.S. Instead, they had to refine skill-based, systematic approaches to the game. This helped to ensure every player developed what is commonly called a “high basketball IQ”.

They also exhibit a high level of adaptability to team-oriented strategies. European basketball exemplifies this, blending the legacy of former socialist sports systems — which prioritized collective success — with contemporary, globalized styles. This structured process explains why European players like Nikola Jokić, Luka Dončić, and Giannis Antetokounmpo often arrive in the NBA with an advanced understanding of spacing, passing, and team concepts.

Jokić’s story is particularly revealing. Growing up in Serbia, he didn’t just play basketball — he played water polo, a sport that demands high-level spatial awareness and precision passing. In water polo, players must make quick decisions without being able to plant their feet or rely on sheer speed. Although, at seven feet tall, Jokić could probably sometimes touch the bottom of the pool!

These skills translated perfectly to his basketball game, where his passing ability, patience, and ability to manipulate defenders make him one of the most unique playmakers in NBA history. Unlike the American model, where taller players are often pushed into narrowly defined roles as rebounders and rim protectors (like I was), European training systems emphasize all-around skill development regardless of height.

This is why European big men like Jokić, Gasol, and Nowitzki excel both in the post and on the perimeter. Europe's emphasis on technical education and tactical intelligence fosters versatile skill sets before specialization. This adaptability has made fluid, multi-positional play the norm, prioritizing efficiency and team success over individual spectacle.

If European basketball emphasizes structure, the African basketball pipeline fosters adaptability and resilience — not as inherent traits, but as responses to developmental conditions. Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu popularized this as habitus, where individuals unconsciously shape their skills based on their social and material environments. With limited formal infrastructure, many African players learn in fluid, improvised settings, refining their game through necessity rather than structured coaching.

Unlike U.S. and European players, who train in specialized systems from an early age, African players often develop versatile, positionless skill sets. Their careers frequently involve migrating through different leagues and coaching styles.

A great example is Joel Embiid. He didn’t start playing basketball until he was 15. Growing up in Cameroon, he initially played soccer and volleyball. These sports both contributed to his basketball development in unexpected ways. Soccer helped him refine elite footwork, now a required trait of the post game, while volleyball sharpened his timing and hand-eye coordination — hence his dominance as a shot-blocker and rebounder.

This multi-sport background is common among African players. Many grow up playing soccer first, which explains why so many African-born big men in the NBA — Hakeem Olajuwon, Serge Ibaka, and Pascal Siakam — have exceptional footwork and agility.

Like Jokić’s water polo background shaped his passing, soccer’s fluidity influences how many African players move on the court. Beyond skills, migration plays a key role, as many leave home as teens to develop in European leagues or U.S. schools. Constant adaptation to new environments builds mental resilience, essential for professional sports. (just ask Luka Dončić after suddenly being traded to the Lakers!)

Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai describes this as evolving ethnoscapes and how globalization drives global cultural flows. Practices, traditions, and ideas reshape both new destinations and home cultures as identities become blended across cultures and borders. African players embody this, adapting their games across multiple basketball traditions.

Look at Embiid moving from Cameroon to the U.S., adapting to American basketball while retaining his cross-sport instincts. Or Giannis Antetokounmpo, he was born in Greece to Nigerian parents, played soccer as a kid, and now blends European teamwork and fancy footwork with NBA strength training and explosiveness. Like the game itself, basketball is shifting as players from diverse domains deliver new directions, playing patterns, and philosophies.

CULTURE, COURTS, AND CROSSOVERS

The influx of European and African players has not only changed the NBA, it’s also changed how American players play overseas.

Sports psychologist Rainer Meisterjahn studied American players in foreign leagues, revealing struggles with structured European play and coaching. Initially frustrated by the lack of individual play and star focus, many later gained a broader understanding of the game. Their experience mirrors that of European and African players in the NBA, proving basketball is now a shared global culture.

While the NBA markets itself as an American product, its style, strategies, and talent pool are increasingly internationalized. The dominance of ball movement and tactical discipline coupled with versatility and adaptability have fundamentally reshaped how the game is played.

Media has help drive basketball’s global expansion. Sports media now amplifies international leagues, exposing fans (like me) to diverse playing styles. Rather than homogenizing, basketball evolves by merging influences, much like cultural exchanges that shaped jazz (another love of mine) or global cuisine (another love of mind) — blending styles while retaining its core.

The game is no longer dictated by how one country plays; it is an interwoven, adaptive sport, constantly changing in countless ways. The court’s boundaries may be tight, but borderless basketball has taken flight.

Basketball has always been a game of spatial negotiation. First confined to a small, hardwood court, it spilled out of walls to playgrounds, across rivalrous cross-town leagues, to the Laker-Celtic coastal battles of the 80s, and onto the global stage. Yet its true complexity is not just where it is played, but how it adapts. The game’s larger narrative is informed by the emergent behaviors and real-time spatial recalibration that happens every time it’s played.

Basketball operates as an interactive system where every movement creates new positional possibilities and reciprocal responses. Player interactions shape the game in real time, influencing both individual possessions—where spacing, passing, and movement constantly evolve — and the global basketball economy, where styles, strategies, and talent migration continuously reshape the sport.

On the court, players exist in a constant state of spatial adaptation, moving through a fluid network of shifting gaps, contested lanes, and open spaces. Every pass, cut, and screen forces a reaction, triggering an endless cycle of recalibration and emergence.

The most elite players — whether it’s Nikola Jokić manipulating defensive rotations with surgical passing or Giannis Antetokounmpo reshaping space in transition — don’t just react to the game; they anticipate and reshape the very structure of the court itself. This reflects the idea that space is not just occupied but actively redefined through movement and interaction, continuously shaped by dynamic engagement on and off the court.

This logic of adaptation extends to the community level where basketball interacts with urban geography, shaping and being shaped by its environment. Urban basketball courts function as micro-environments, where local styles of play emerge as reflections of city life and its unique spatial dynamics.

The compact, improvisational play of street courts in Lagos mirrors the spatial density of urban Africa, just as the systemic, team-first approach of European basketball reflects the structured environments of club academies in Spain, Serbia, and Lithuania. As the game expands, it doesn’t erase these identities — it integrates them. New forms of hybrid styles reflect decades-old forces of globalization.

Basketball’s global expansion mirrors the complex adaptive networks that form during the course of a game. Interconnected systems evolve through emergent interactions. And just as cities develop through shifting flows of people, resources, and ideas, basketball transforms as players, styles, and strategies circulate worldwide, continuously reshaping the game on the court and off.

The court may still be measured in feet and lines, but the game it contains — psychologically, socially, and geographically — moves beyond those boundaries. It flows with every fluent pass, each migrating mass, and every vibrant force that fuels its ever-evolving future.

REFERENCES

Hillier, B. (2012). Studying cities to learn about minds: Some possible implications of space syntax for spatial cognition. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design.

Naismith, J. (1941). Basketball: Its Origins and Development. University of Nebraska Press.

Baur, J. W. R., & Tynon, J. F. (2010). Small-scale urban nature parks: Why should we care? Leisure Sciences, Taylor & Francis.

Callaghan, J., Moore, E., & Simpson, J. (2018). Coordinated action, communication, and creativity in basketball in superdiversity. Language and Intercultural Communication, Taylor & Francis.

Meinig, D. W. (1979). The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays. Oxford University Press.

Andrews, D. L. (2018). The (Trans)National Basketball Association: American Commodity-Sign Culture and Global-Local Conjuncturalism.

Galeano, E. (2015). The Global Court: The Rise of International Basketball. Verso.

Ungruhe, C., & Agergaard, S. (2020). Cultural Transitions in Sport: The Migration of African Basketball Players to Europe. International Review for the Sociology of Sport

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. University of Minnesota Press.

Meisterjahn, R. J. (2011). Everything Was Different: An Existential Phenomenological Investigation of U.S. Professional Basketball Players' Experiences Overseas.

Ramos, J., Lopes, R., & Araújo, D. (2018). Network dynamics in team sports: The influence of space and time in basketball. Journal of Human Kinetics.

Ribeiro, J., Silva, P., Duarte, R., Davids, K., & Araújo, D. (2019). Team sports performance analysis: A dynamical system approach. Sports Medicine.