Hello Interactors,

Hints of loosening COVID restrictions are wafting through the air like a contagious air-born disease. Does this mean people will be heading back to work? Some can’t wait, some would rather not, and others would love to have such a luxury to consider. Is remote work here to stay? And if so, are we sure it’s healthy?

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

COMFORTABLE BUSINESS

He had just returned to the office for the first time in two years. I asked him what it was like. I wondered how many people were there with him. He responded, “Let me put it this way, when I pulled into the parking garage I counted maybe six cars.”

I was having lunch with a couple Microsoft friends recently. Our conversation started there and then turned to the current hiring climate in the tech industry. Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and a dizzying array of startups are all vying for talent. They’re offering insane starting salaries, stock grants, and signing bonuses. But there seems to be one non-negotiable with tech workers – flexible working arrangements.

Before we knew it, the three of us were talking about what cities would be best to live in knowing employers don’t really care where you live. But even among well-paid tech workers, cost of living became the most salient factor in choosing an ideal city. Rising real estate prices pose the biggest challenge, but optimal internet speeds were up there too.

One friend, who had recently left Microsoft for a startup, mentioned the downsides of remote work. She said it’s really hard getting to know a team you’ve never met in person and even harder for them to get to know you. She senses judging and fields odd questions that aren’t about her, but about her role and what she’s being asked to do. And broad communication from their CEO seems to always fall flat. She said he comes across as disingenuous, less human, and overly focused on short term deadlines and quarterly results. Reflecting on our time working together she’s said she really valued the ‘non work’ interactions that happened on our team. We did feel more like a ‘family’ than a ‘squad.’

Two years of disrupted work practice has led to a combination of ‘the great shuffle’ – people swapping companies in search of higher pay and benefits, ‘the great displacement’ – rising cost of living involuntarily pushing lower paid workers from their homes, or ‘the great resignation’ – cost cutting companies incenting early retirements or aging workers opting to retire early. It’s left companies wondering if this is a phase or if people have habituated to increased flexibility. The CEO for Stitch Fix, an personal apparel shopping service, said they’re seeing customers looking to replace a third of their wardrobe with what they call “Business Comfortable” clothes. She says their customers want to stay working in sweats, but want them to look more ‘professional’ when on Zoom calls.

Cities and local businesses are impacted too. Can they count on workers coming back in droves to commercial districts buying breakfast, lunch, coffee, and drinks? Or even haircuts. Nikita Shimunov owns a barbershop in Manhattan where he once saw 50 to 60 men pass through his shop in a day. It’s trickled to 10 to 15 customers daily and he’s been forced to reduce staff by half. His financial future hinges on the empathy of his landlord.1

Many cities rely on these tax revenues to fill their coffers. But if masses of people stop going in to work, it has huge implications on urban planning. Microsoft is wrapping up the final touches on a massive new corporate campus in Redmond at a time when many, maybe even most, may remain working remotely. It’s next to a brand new light rail stop planned and designed to serve thousands that now may never come.

Not all flexible work arrangements are the same or even desirable. Flexibility can introduce or amplify home and work conflicts for individuals, teams, companies, cities, and regions. Technology, especially mobile technology, has been blurring work and home boundaries for decades. What does it mean to achieve a work/life balance when the boundary disappears? And for those with young children, the burden of parenting, home schooling, and working can become overwhelming. And given our social norms, that burden largely, and unfairly, falls on women.

Women are also unfairly expected to conform to certain traditional workplace ideals that focus on physical appearance and presence. For example, wrestling with a screaming toddler on a Zoom call with un-brushed hair, no makeup, and no sleep can make some people judge her as ‘not being professional’. And come review time, how might some managers reflect on these interactions when it comes time to hand out pay increases or offer new opportunities for growth? Meanwhile men get to poke fun at each other for wearing pajamas and having bed head.

I had a remote employee years ago and my biggest fear was that she seemed to always be available. Remote workers can sometimes over communicate or stretch their availability. They can over compensate for not being physically present. But being always ‘on’, ‘available’, and ‘connected’ can lead to burnout. These pressures, self-inflicted or induced, can also lead to exhaustion and mental duress. Some anthropologists believe humans did not evolve as we did by working even eight hours a day, let alone 12 or more. It doesn’t necessarily lead to optimal team performance either.

Individual suffering can spill over to co-workers which creates even more stress and burnout. Team members can become withdrawn which exasperates feelings of isolation and loneliness. Quiet, more subdued, colleagues can also feel excluded or overlooked. Some choose to turn their cameras off to combat feelings of personal intrusion or surveillance. Or maybe they’re hiding their bed head. This can ultimately lead to job dissatisfaction prompting them to seek another team or company.

I know from experience how attrition can spread like an infectious infliction as those who leave prompt others to do the same. Perhaps ‘the great shuffle’ we’re experiencing isn’t just people running toward opportunity, but impunity.

IS FLEXIBILITY THE FIX?

Flexible working arrangements can take on a variety of flavors and can be called many things. Even before the pandemic, Microsoft had always had what they called ‘flex-time’. It simply means your manager doesn’t really care when you come and go so long as you get your work done. But these days flexible working arrangements can be called names like “remote work”, “tele-commuting”, “tele-work“, “mobile work”, or “virtual work”. There are also those who are “self-employed”, “on-call”, “on-demand”, or working in “shared spaces”.

A group of business school researchers at the University of Reading in the UK just published a literature review on research focused on flexible work practices. They came up with a taxonomy that clumps arrangements into four categories:2

Remote, Spatiotemporal, On-demand, and Self-directed. Remote work is like the COVID caused ‘work from home’ many are experiencing today. Spatiotemporal work includes shared spaces, ‘touch down spaces’, ‘office clubs’, and even ‘job sharing’. On-demand work is for workers who are on-call like Uber or Grubhub drivers. Self-directed workers own their own companies, freelance, or contract.

Each of these come with their own advantages and disadvantages. Working from home, or Remote work, is what most people think of when considering flexible working arrangements. Products like Microsoft Teams and Zoom, and a growing list of alternatives, make it easy to ‘plug-in’ remotely. Like, for example, joining a meeting from wherever you may be.

I was on a walk one summer morning before sunrise in some nearby woods when I had to join a meeting scheduled in another time zone. So I sat on the limb of a fallen tree over looking a wooded ravine and took part in the meeting as the sun rose. Halfway through, however, the limb snapped and down I went. Good thing the camera was off. And, yes, I was muted.

But these remote work products, including Slack, Teams, Zoom and others, allow for both synchronous and asynchronous communication. This can lead to days and evenings filled with either a meeting, interruptions from notifications and alerts, or the dreaded FOMO – Fear Of Missing Out – a fear that addicts people to be constantly checking and dealing with email, channels, or text message threads. In other words, constantly working.

This invariably infringes on time spent with family and friends. These prolonged stresses can drive some people to withdrawal and become isolated. And for those who seek control and domination over others, like manic micro-managers, it means they can wield these real-time, always on, communication tools like a weapon. And the quicker people respond to their seemingly psychopathic needs, the more fervent their interruptions become. It’s a cycle that can leave people anxious, depressed, and looking to get away. Those feeling violated in their own homes sometimes seek a shared workspace elsewhere.

Sharing work spaces over different times and places is what researchers call Spatiotemporal work. This style of working hit the news a few years ago when the shared workspace company WeWork failed its initial public offering (IPO). Started in 2008 as GreenDesk – an “eco-friendly coworking space” – it became WeWork in 2010 with an infusion of cash from a wealthy real estate developer. By 2014 it was “the fastest-growing lessee of new office space in New York”. They grew too quickly and imploded in their 2019 IPO, refinanced and went public in 2021, and are now leveraging rising COVID driven real estate prices to recoup some of their losses. While their memberships still remain low, the pandemic has created a growing need for humans to come together physically to collaborate and bond. Especially as team members are scattered across regions, countries, and the globe.

Microsoft, like many organizations, have long used ‘off sites’ as temporary ways to pull teams together for a day or more – a kind of spatio-socio-temporal team building field trip. Some I attended were more sashay to build cachet than work with a perk, but some companies are now using these excursions as more routine means of encouraging more physical collaboration. New software tools like Cloudfare make it easier for managers to schedule and arrange gatherings of geographically dispersed employees in places like AirBnb’s, employee’s homes, or even existing offices – an on-site off-site.

Some companies are even allocating money to teams so they can book these off-sites themselves as a way to bring team members together physically – even if it’s just for a picnic, a walk in a park, or a bike ride. Some companies are even buying apartments or hotel suites as more permanent ‘off-site’ locations. The Wall Street Journal reports that one 26 person startup, Aidentified,

“rents two corporate apartments, one in Boston and one near San Francisco, in lieu of offices, so employees can gather when needed. Each apartment is equipped with a conference table, seating areas, a kitchen and bedrooms where out-of-town employees can stay.” The 3,000-square-foot, three bedroom, multi-level Boston apartment has an outdoor terrace overlooking the Boston Public Library.

If this sounds extravagant, it is. Companies rich with cash can often become embarrassments of riches. This competitive hiring climate exists within a grossly disproportionate wealth disparity that compounds these excesses as each company seeks to out do the other in attempts to lure and retain employees. But these off-sites need not always be entirely self-serving. The nonprofit Forté Foundation, a women’s business leadership advocacy group, took some time during their three-day off-site in Austin, Texas to build bikes for a local nonprofit…in between pamper parties, luxury lunches, and extravagant excursions of course.

For those laboring behind the scenes to prop these posh parades of privilege, it’s hard to see any of this as actually being ‘work’. Many managers funding these fun fests often wonder the same thing. In order for managers to know whether these remote employees are actually working or not requires more software. Task management and planning tools like Confluence, Trello, Project, Planner, or Basecamp let managers keep an eye on task completion, deadlines, and engagement. But this can make some employees feel like they’re being watched, scheduled, and controlled. The opposite of flexible, but still far from indentured manual labor most of the employed world endures.

AN ANT ANTEDOTE

Shared work, space, and calendars are sold and celebrated by the software industry as new cultures of openness and inclusion, but not everyone is equally comfortable sharing their locations and schedules. Others find the overhead required to fill out forms, schedule tasks, and report progress inhibits their ability to actually be productive. And when tasks are shared among team members, it’s not always clear who was responsible for doing what. Often times the bulk of the work falls on those most conscientious or those seeking glory and control. Managers are then stuck with no clear way of evaluating contributions fairly. That is if they can get employees to actually fill out their forms in the first place.

In addition to rogue, power hungry, and individualistic workaholics dominating a team, sporadic sharing work practices centered around short-term deliverables can also lead to groupthink. In an effort to complete tasks, individuals can be prone, even encouraged, to taking the path of least resistance instead of finding more creative and effective solutions that may be out of the norm. These can all have financial implications for companies as product quality may suffer, or those less geared for these sharing cultures and workspaces could suffer a loss in compensation or opportunities.

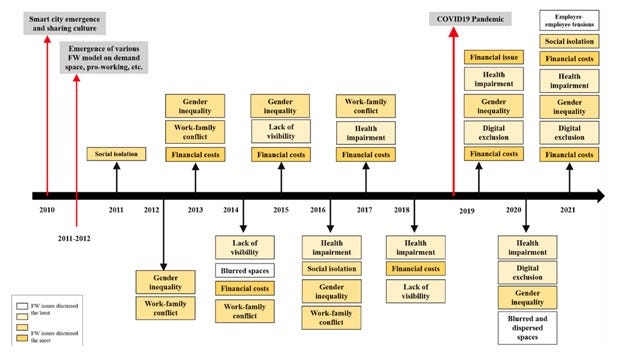

The results of that UK literature review revealed that researchers have been trying to tease apart the impacts of flexible work practices since the emergence of so-called ‘Smart Cities’ and ‘Sharing Culture’ around 2010. Within a year social science researchers were already looking into aspects of social isolation. By 2012 themes of gender inequality and work-family conflict entered the scene. Then came financial costs, lack of visibility, blurred spaces, and health impairment. And then, after COVID came to town in 2019, these topics blew up. And by last year, 2021, the themes of dispersed spaces and employer-employee tensions were added to the decade old list of concerns.

These researchers observed that, “while almost all the studies have explored both the positive and negative consequences of technology use, none have examined the downsides of changes in (or to) technological platforms on employee behavior and work.” They were surprised to find that

“researchers have not explicitly focused on the changes in traditional hierarchies and the dynamic nature of manager–employee relationships as a result of technology-enabled [Flexible Work Practice].”

They say existing research aims to understand technology as a facilitator of flexible work “thus perpetuating the instrumental view of technology.”

Given this finding, they call on a shift in perspective. Instead of just explaining the role technology is playing in enabling flexible work practices, seek to describe the social force it plays in shaping our behavior which in turn shapes our networks of relationships. They wrote, “Given the active role that technological platforms continue to play in organizational life, other conceptualizations of technology are required…” One theory they suggest leveraging is Actor-Network Theory (ANT).

The International Encyclopedia of Human Geography describes Actor-Network Theory as a

“unifying thread [that] constitutes the central line of connection to the field of human geography.”3

It’s an ever evolving social theory that argues

“all manner of things (as many as you can imagine) are variously entangled together in specific formations or networks in the making of the world.”4

As I stand here in Kirkland, Washington on the 18th birthday of my son and daughter, I can look back over those nearly two decades and see the role technology has played in bringing that central line of connection in human geography into focus. The combination of the internet, mobile technologies, and geo-political globalization have connected an assortment of ever expanding networks of people and place. And then, in the final three years of my kid’s high school existence I can see how that technology has both granted them needed flexibility but also robbed them of social opportunities.

But despite it all, they have flourished. And yet not all kids have – nor have adults. As affluent, mostly white, remote workers enjoy their ‘flexible working arrangements’ – like next day Amazon orders, late night GrubHub ice cream deliveries, and TaskRabbit handy man assignments – those ‘on-demand’ workers on which they rely suffer their own perplexing paradoxes. While ‘on-demand’ work has supplanted needed income for many struggling to make a living, it’s also taken a toll on their health.

Because laws lag in defining and representing the rights of these workers, they’re prone to exploitation by corporate overlords and overly demanding and consuming customers. It can lead to job related and economic anxiety, stress, and uncertainty. And because they operate alone, without a tightknit team – a family – it leaves ample time to reflect on their plight. They can become preoccupied with how society, their government, their companies regard, treat, and abuse them.

As I walked home from that lunch with my friends last Friday, I looked around my little town of Kirkland. It’s been shaped by nearly a century and a half of people – actors – enrolling, transforming, and interacting within nested networks of natural and engineered environments. Kirkland was intended to be a steel town. Peter Kirk’s vision was for it to be “The Pittsburgh of the Northwest.” The Peter Kirk building is now the Kirkland Arts Center. Ole Pete could never have imagined any of this. Just as we never imagined we’d be forever shaped by a measly virus.

I looks like my next lunch with friends will likely be unmasked. Washington is currently planning for mask free restaurants at the end of March – more flexible eating arrangements will soon be meeting flexible working arrangements. I’ll be curious to see whether more Softies return to the Redmond campus over time or whether the future of their work remains primarily remote. It’s hard to tell without a string of caveats.

This tiny microbe has disrupted an entire global actor-network. Just how much our behavior has been changed permanently is unknown, but there’s no going back to some semblance of ‘normal’. The future is as uncertain as predictions for how far into the future the global pandemic will continue to circulate. As Dr. Heidi Brown, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Arizona said recently,

“Until the epidemiologists can tell you what’s going to happen in the future without massive uncertainty caveats, then we’re still in an epidemic-type situation.”5

Hold on to your hats, and your masks, we’re all about to learn there is not such thing as a free lunch.

People Are Going Out Again, but Not to the Office. Peter Grant. Wall Street Journal. 2022.

Unmasking the other face of flexible working practices: A systematic literature review. Lebene Richmond Soga, Yemisi Bolade-Ogunfodun, Marcello Mariani, Rita Nasr, Benjamin Laker. Henley Business School, University of Reading, UK. 2022.

Actor Network Theory. ScienceDirect. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. 2009.

Ibid

What Does Endemic Mean and Will Covid-19 Become an Endemic Disease? Brianna Abbott and Gabriele Steinhauser. Wall Street Journal. December, 2021.