Hello Interactors,

Most people’s awareness of the economy starts with three letters: GDP. It seems every news report about the health of any nation starts with their GDP. And there is only one direction it can go for anyone to be satisfied and that is up. Even though we all know that as those numbers go up the health of our environment goes down. How did we get here?

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

BEN AND ARIES

In 1817, German poet, playwright, and scientist, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote,

“Every school of thought is like a man who has talked to himself for a hundred years and is delighted with his own mind, however stupid it may be.”

Goethe himself fell victim to this, but it’s unlikely he considered his ideas stupid. No member of any school of dogma does. He considered himself a cut above the rest; a genius in fact. At least as defined by his more famous German peer, philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Goethe was a naturalist and believed his genius was his ability to translate his knowledge of the natural world into manmade civic matters – like economics. He was equally adept at using words like “budget, balance, economy, law and order” in describing the workings of the German government as he was describing his gardens. Or mines. Goethe was put in charge of managing area parks, mines, and forests which gave him ample opportunities to marry elements of botany and geology with economics.

He was following in the footsteps of the French economic school of thought from the mid-1700s, The Physiocrats. They too believed in the order of natural law. They thought “the only choice humans had was either to structure their polity, economy and society in conformity with the ordre naturel or to go against it.” Talk about being dogmatic.

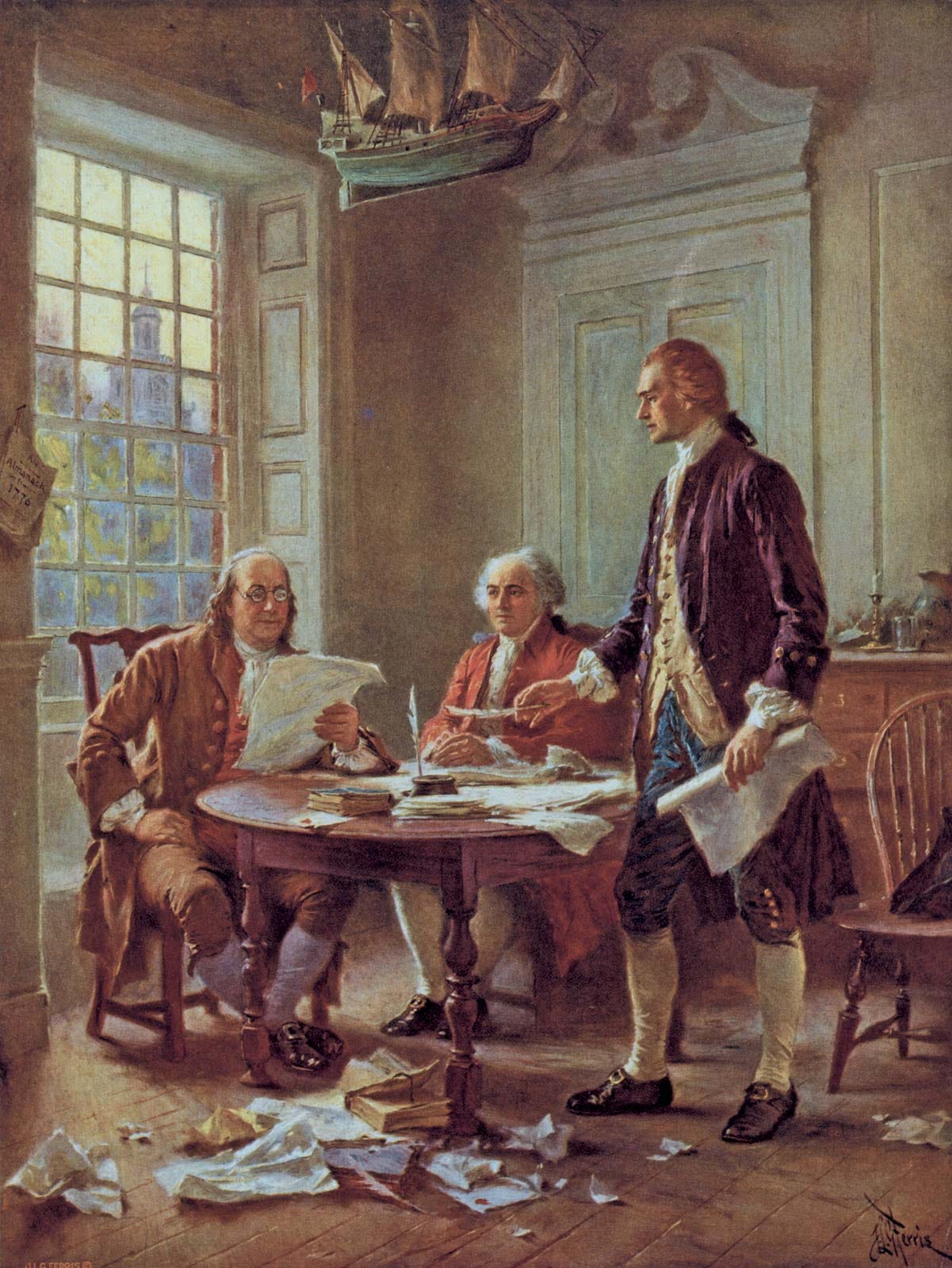

There were some big names in this school of thought; including Benjamin Franklin. He sided with the Physiocrats arguing the only real productive contributions to a nation’s economy was naturally – through land ownership and farming. It’s a school of thought that propelled Thomas Jefferson, also a land loving naturalist, to push for land grabs across the country for the purpose of farming and land taxation. It’s also what separated the industrial mercantilists of the America’s North and the agrarian agriculturalists of the South which eventually led to a civil war.

Colonialization, at its heart, was about land acquisition for agriculture, industry, transportation, international trade, and real estate. It was also about ethnic, racial, and gendered economies, and eventually the development of urban form. It set out to dominate the interaction of people and place. It was also the emergence of the field of economic geography.

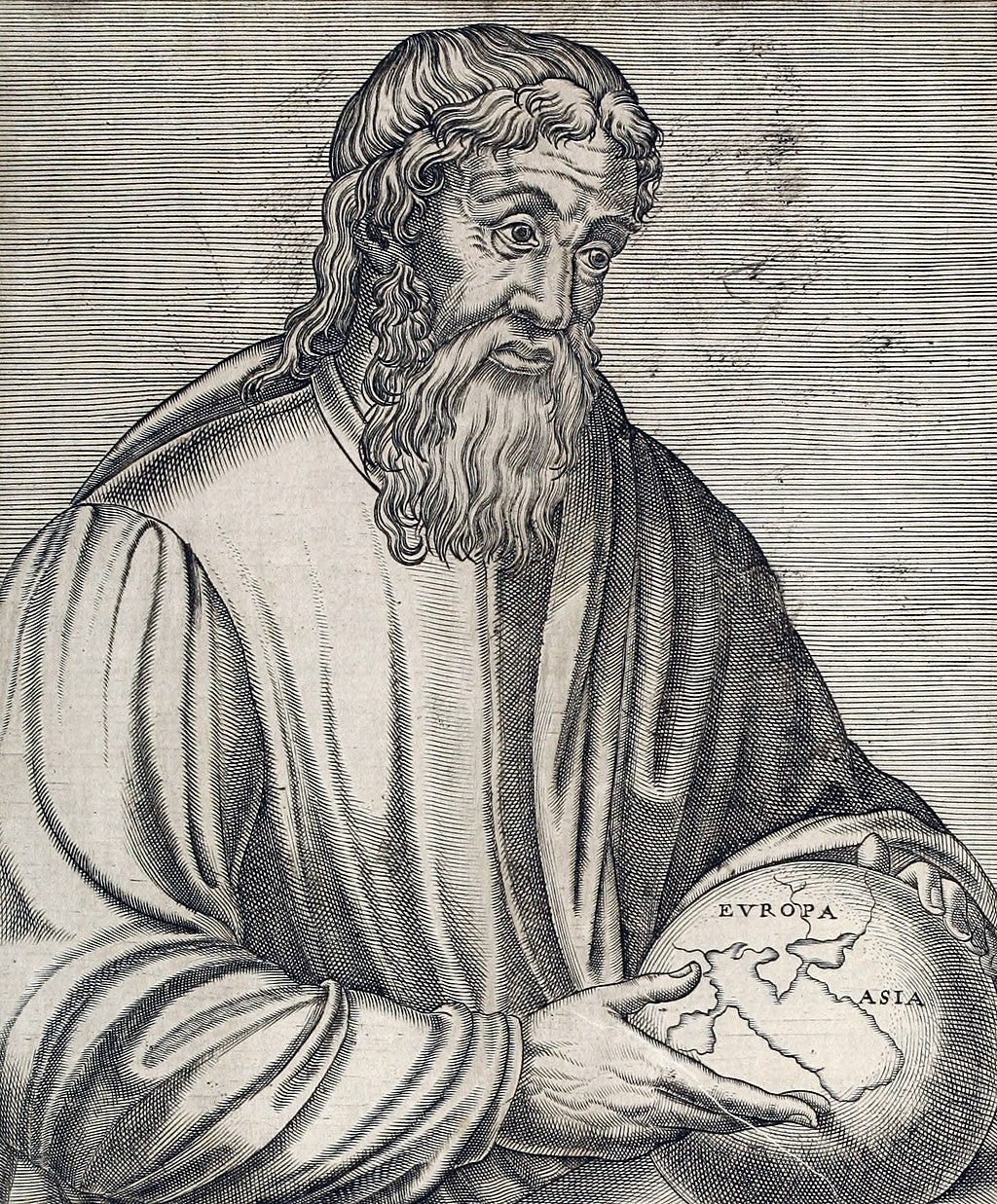

But long before the Enlightenment and colonization, in 4th century BC, the State of Qin in western China developed timber maps that included locations and distance measures to the sites. These are some of the oldest economic maps in the world. And then along came the Greek philosopher Strabo. He published a book called Geographica just before his death in 24 AD. It was found and reprinted in Latin in 1469 and describes the interactions of people and places from around the various parts of the world Strabo visited, including their economies.

This reprinted work proved more influential to the burgeoning Enlightenment thinkers of 15th century, than Strabo’s first century contemporaries. Either way, economic geography took hold in Europe throughout the Enlightenment and into the 19th century as Goethe was writing erotic plays, listening to Beethoven live, and dabbling in economics between trips to the garden.

NEW-MATH MEETS HU-MAN

Strabo’s work would have been picked up by another German, Alfred Weber – the brother to one of the founders of modern-day sociology, Max Weber, who believed capitalism came to exist through the protestant work ethic. Max ended up winning the ‘who will be most famous’ yearbook prize, but Alfred likely would have been more popular at the time.

He made a name for himself as an economist developing some of the first theories on industrial location in 1929. He wanted to know why and how industries, cities, and farms determine where to locate. So, he developed analytical and interpretive methods to do so.

Citing agglomerations, a collection of contiguous cities, industries, and labor pools, Weber was likely influenced by one of the most prominent British economists of the time, Alfred Marshall. He authored the 1890 book, Principles in Economics, and was the founder of yet another economic school of thought – The Cambridge school of neoclassical economics. We’ll learn more about Alfred later.

Weber and Marshall were also influential outside of Europe. Weber’s work made its way to North America by way of a young mathematician named Walter Isard in the 1940s. Isard was a Quaker and thus a conscientious objector during World War II. His civil service was then satisfied as an attendant in a mental hospital.

He had recently earned his PhD in Economics from the University of Chicago where he was inspired by Weber. He spent his time at the hospital translating Weber’s work from German into English. He went on to teach regional science at MIT, started the first doctoral program in regional science at the University of Pennsylvania, and rounded out his career at Cornell in 1979. He died in 2010 as one of the most influential quantitative geographers in the field.

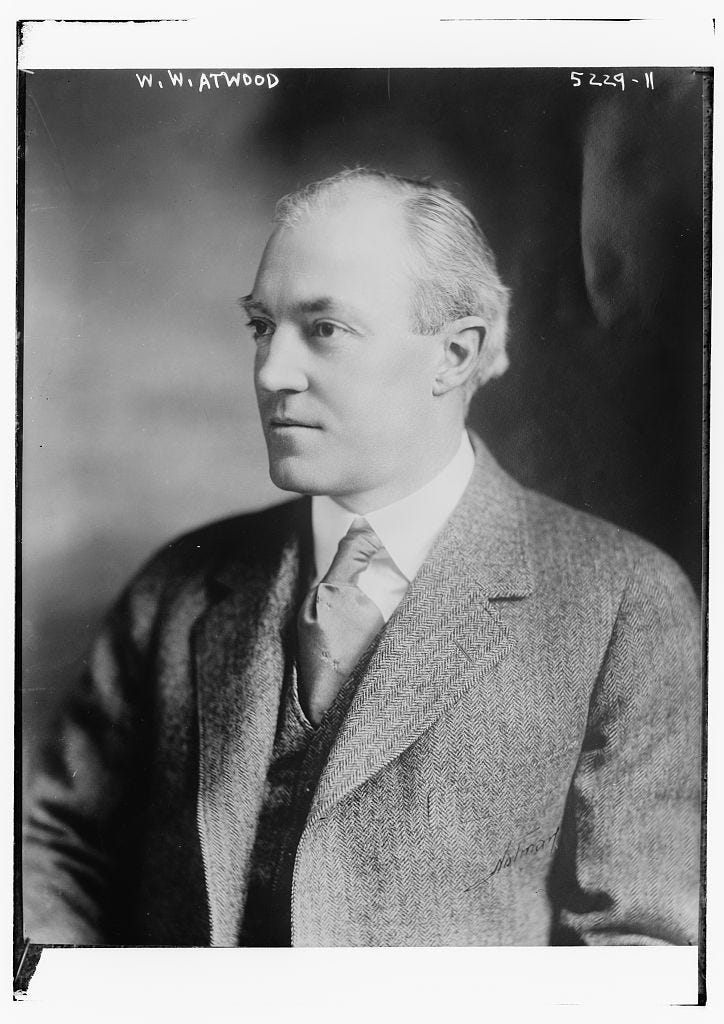

But while Isard was still a young boy, another strand in economic geography had already been started in America; but from a humanist standpoint. Geographer and geologist, Wallace Atwood, also a University of Chicago graduate, had published a book in 1920 called Teaching the New Geography. It was targeted at elementary school teachers and encouraged a more progressive method of teaching geography to young people that avoided rote memorization of place names.

Page one states that Atwood believes,

“the study of geography in the elementary-school stage should do more than…provide geographical facts – it should give them a real understanding of…a definite power of interpreting their effect on human life.”

He goes on to state,

“Fortunately, we have now learned to teach the facts of place, political, physical, economic, and commercial geography in association with the more vital, more interesting, and more thought-provoking topics of human geography. In other words, we have come at last to focus the study on people, not things.”

Atwood became the founding editor of the journal of Economic Geography out of Clark University in 1925 and eventually became the school’s president. The journal continues today to “redefine and reinvigorate the intersection between economics and geography” and is the discipline’s leading academic journal.

HEAD AND TAILS

These two schools of thought and approach, technical and naturalist, were both indicators and influencers of the larger field of economics and politics. But they were also two sides of the same coin. On one side, there was a top-down, mathematical interpretation and explanation for what was occurring spatially as goods and people moved through space and time. This approach to economics emerged out of the work of Weber, Isard, and others in Europe and North America who are fondly referred to as the ‘space cadets’. There work complemented another emerging field in economics called econometrics – the application of statistics to economic relationships.

On the other side of the coin were the earthy-crunchy, naturalists. The roots of the French Physiocrats grew into Germany creating sprouts of ideas tended to by people like Goethe. Seeds then spread to America and were planted by Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. Their land rights and agricultural economic beliefs blossomed into a gridded patchwork of townships, farms, cities, roads, and waterways that stretched across a continent.

Colonial settlers toiled and tilled yielding fruits of labor in the form of property taxes and crop revenue. The funds of which built a military that protected industrialists seeking access to sacred Indigenous land to lay tracks for trains and mountains for mines.

Cities grew across the oceans connecting the northern hemisphere with diverse populations of people cross-fertilizing ideas, yielding new seeds of inventions and innovation, that continued to spread around the world through interconnected vines of nutrient rich endeavors. All of which were extracting natural resources and exploiting human labor at rates never seen in the history of the world.

By the 1900s the industrial age had lined the pockets of the economic elite, coal fired steam stoked success, but also paired pollutants to particles that penetrated the lungs of those less lucky. Trees were toppled, canyons collapsed, and sand stripped of their sediment. It was enough to prompt the Republican naturalist President Teddy Roosevelt to regulate railroads and conserve natural resources; an attempt to give Americans and the environment a “square deal”.

His actions encouraged people like Wallace Atwood to pause and grow concerned. Atwood hoped to inspire a generation by asking children of the 1920s to be thoughtful about the power people have over interactions between physical geography, politics, place, and the effect they have on human life. Imagine where we’d be today if Atwood’s books and words actually took hold. I don’t know about you, but my primary geography education was still pretty much about memorizing Anglo-American names of cities and states around the world.

This coin of economics offers mathematical quantitative spatial and econometric measures that include indicators of success for world-wide economies, on one side, and the other a naturalist-inspired human-environmental articulation of the potential positive and deleterious effects on physical geography and life. The measures of one side of the coin are even inspired by words of the other, like ‘health’ and ‘growth’.

But the two sides suffer from a perverse cycle of codependency that lingers to this day. For example, we live in a society that measures, rewards, and celebrates how increased sales of automobiles contributes to the ‘growth’ of an economy knowing full well their presence is destroying the ‘health’ of the environment and its inhabitants.

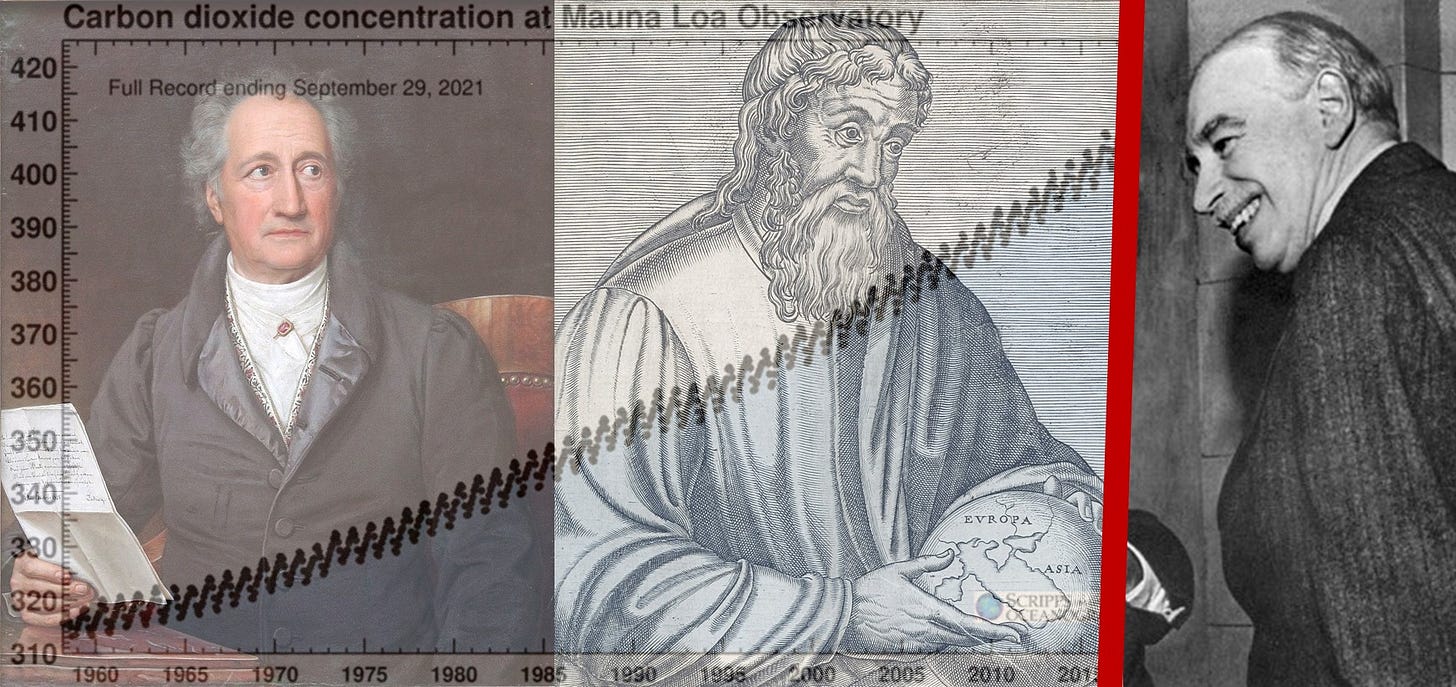

As gas prices plummet, economies grow – and so does the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Higher wages mean more consumerism and economies grow; and so does the size of toxic landfills and islands of plastic in the ocean. More cars on the road yield more accidents and more injuries and deaths. But they also yield economic growth in the insurance, auto, and healthcare industries as insurance, repair, and medical bills pile high. Economic indicators that rise, also measure our demise. We need no better proof that humans do not act logically nor rationally.

THE AIMS AND PAINS OF KEYNES

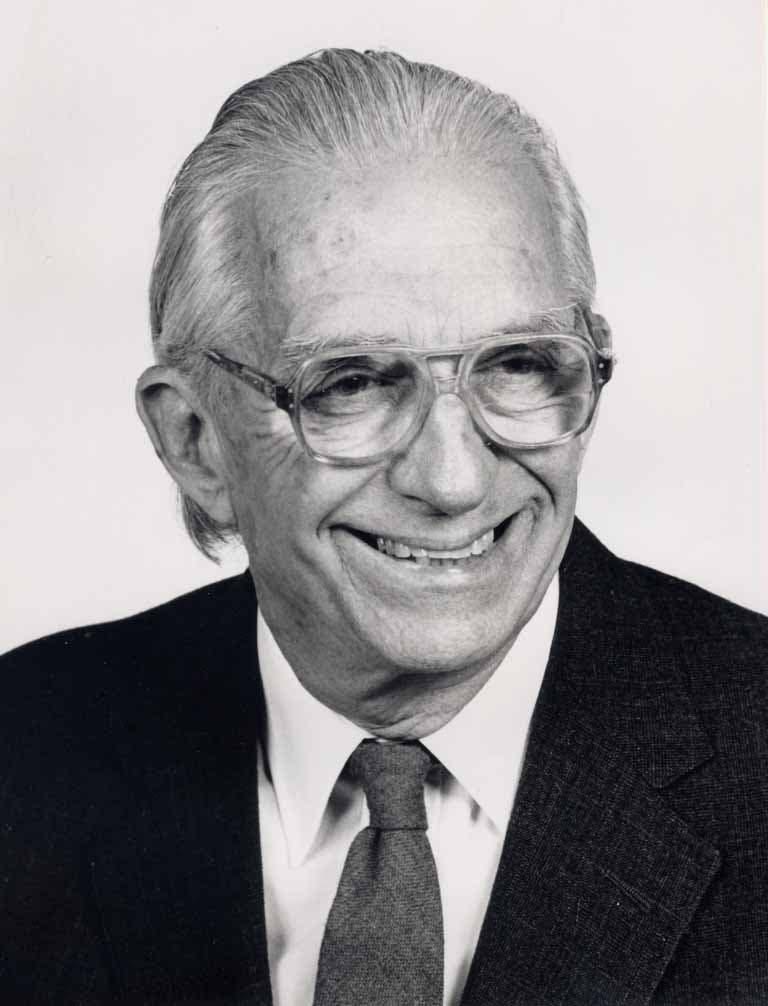

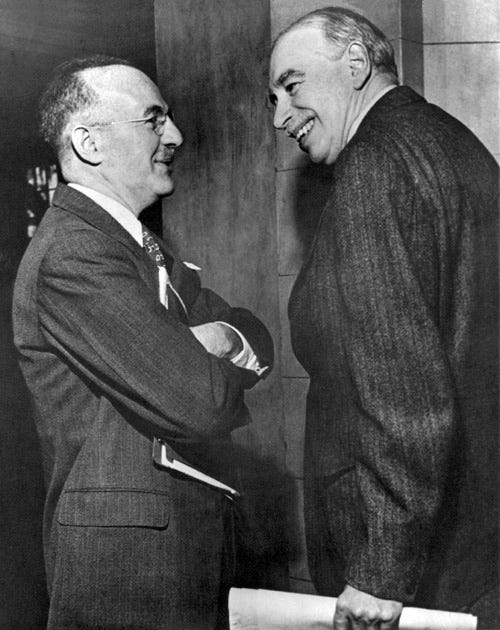

But that would have been a tough argument to make in the late 19th and early 20th century. Most mainstream economists today would still argue. Arguments that stem from the principles of the preeminent 20th century British economist, John Maynard Keynes.

Remember Alfred Marshall, the father of the Cambridge school of neoclassical economics? Keynes was a family friend and protégé of Marshall’s and expanded on his ideas, attitudes, and beliefs. One of which was the notion that people’s subjectivity in decision making plays a small role.

In his 1921 Treatise on Probability Keynes wrote that when we are faced with a decision, we weigh the facts based on the knowledge we have. The decision that follows is “fixed objectively, and is independent of our opinion.” A probable choice “is not probable” just because we think it is. Some mythical natural law has determined it.

I don’t know about you, but despite the knowledge I possess about the negative effects of sugar, it’s probable that I’ll have dessert because in the opinion of my sugar craving brain, I deserve it. And while I know the ocean is full of plastic, it is probable that I will continue to buy plastic products because, in my opinion, I think I want that product. But who am I to judge an Eton grad and one of the most influential people in the history of economics? He must be right. Right? In my opinion, not really.

Keynes’ biggest contribution to economics, and the world we live in today, came in his 1936 book, General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Here he outlined how an economy could be a nationwide entity bounded by certain governmental policies. These policies act as levers, to use a industrial metaphor, that control prices, interest rates, and even consumer demand – consumers who are governed by natural laws of objective logic uniformly identical to any other human.

By positioning humans as yet another cog in a machine, economists could more easily substitute human behavior into their mathematical models. While some, like Cambridge Philosopher Frank P. Ramsey, disagreed with Keynes, and developed alternative mathematics to demonstrate it, Keynes beliefs survived. In large part because should each individual act on their own accord, subjectively, it would be seemingly impossible to mathematically model the outcome. And where’s the fun in that?

Economists across Europe and North America agreed. By the end of World War II, Keynesian economics dominated economic scholarship and practice. It’s the model we have today and can be characterized in these four economic processes:

Economies are external to our lives. One of the most efficient ways to trick people into believing this fallacy is to put the word ‘the’ in front of Economy. The mechanical metaphors also help to position economic processes as something external to our lives; just like machines.

Economies operate under their own internal logical and objective rules. Entire cultures and societies may come and go, but economies are unaffected. Political parties come and go, but economies remain omnipresent. Diverse societies and religions may rise and fall throughout space and time, but economies remain constant and monotheistic.

Economies operate on a national scale. The mathematical techniques and apparatus surrounding the analysis and reporting of economies represent the success or failure of an entire nation. It was as early as the 1940s that the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) became the primary indicator of a nation’s economic health. These measures allowed for inter-national comparisons and worldwide economic systems like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Economies must be operated and managed through governmental intervention. This is the key to perpetual economic growth. Governments not only can make it possible but it is their duty to do so. Politicians latched on to this idea quickly, which is why Republicans and corporations stacked collegiate economic departments with Keynesian thinkers and funded their research.

It’s been 100 years since Keynes published his economic treatise. That’s ten decades of Keynesian economists convincing each other their school of thought is right by pointing to perpetually climbing GDP numbers while ignoring the climbing curve of carbon dioxide concentration. The words of Goethe still ring true:

“Every school of thought is like a man who has talked to himself for a hundred years and is delighted with his own mind, however stupid it may be.”

It’s not hard to look around to see the students of this school of economics have failed. Our social foundations have been rocked. Our food, water, health, energy, education, social networks, income, work, housing, gender equality, peace and justice, social equity, and political voice are all suffering. And all that surrounds us too: climate change, ozone depletion, air pollution, biodiversity loss, freshwater withdrawals, chemical and soil pollution, and ocean acidification are pushed to their limits.

But here’s what gives me hope. If it took just 80 years to dig this hole we’re in, I’m confident we can find our way out in less time than that. I’ve painted a narrow and bleak picture of mainstream economics, but know there are many economists around the world with alternative theories and practices. I’ll be exploring some in future posts.

But the Keynesian school is what I want to replace.

So here are some things to embrace.

My school says: economies are embedded in the interactions of people and place.

Economies emerge as people converge in a perpetual swirling of reactions.

Social foundations and friendly relations are what make the economic milieu.

But without clean air and water too, any economy is doomed.

So embrace the patterns as complexities emerge among people and place interactions.

References:

Economic Geography: A Contemporary Introduction, 3rd Edition. Neil M. Coe, Philip F. Kelly, Henry W. C. Yeung.

Goethe's Economy of Nature and the Nature of His Economy. Myles W. Jackson. University of Cambridge. 1992.

The History of Economic Thought. Gonçalo L. Fonseca. Institute for New Economic Thinking.