Hello Interactors,

Two years ago yesterday, the first case of COVID-19 in the U.S. was reported just north of Seattle in Everett, Washington. By the end of the month, my town, Kirkland, became famous for more than just the brand of Costco toilet paper. It was the site of the first serious outbreak of COVID in the United States. How many more years will this last? It all depends on if we’re honest with each other and behave ourselves.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

I WANT YOU

It wears many crowns: multae coronae; this virus, this disease. CO-VI-D. COVID. We watched as its thorny tips gripped the tender tissue deep in the lungs of unsuspecting Chinese victims in Wuhan. Replicating, mutating, devastating. Like many crowns before, it sought expansion; new territories to explore, humans to exploit, and lives to destroy. But not the impenetrable America, we thought. Not immutable Americans. Epidemics are for poor countries. Others. What collective stupidity.

Viruses know no borders. America’s first serious outbreak of the Novel Coronavirus occurred in a health center just over a mile from my home in Kirkland, Washington. Like any invader, it scared people into their homes. First reactions were to stay clear of the facility from whence it was spreading…and anyone who may work there.

Doctors and nurses at the home were early spreader suspects. Would they spread it to hospitals, other patients, or their families? Not yet knowing how it spread or how to avoid it, early advice was to simply wash your hands. Wash everything – your clothes, your groceries, and even your Amazon packages. Masks were regarded as ineffective by many U.S. medical pundits and practitioners. Wash your hands, they said.

The United States has a history of denial when it comes to epidemics. When the Spanish Flu was first reported in 1918 in a U.S. Army camp in Kansas, the U.S. had just entered World War I the year prior. Citizens of warring countries in Europe, including Great Britain, were experiencing outbreaks of the flu but were loathed to report it. They feared their enemies would know their troops were vulnerable and weakened. They also didn’t want the public, especially draftees, to fear both the war and an epidemic. And they wanted the media to focus attention on the war, not public health.

Spain, who’s King had contracted the flu, was neutral during War World I so freely reported the outbreak that was soon to be ravaging Europe. The Spanish flu did not originate in Spain, just the honest reporting of it.

The U.S. government, and its high ranking military, were equally hush on the outbreak. It didn’t help that two months after the first reported case, Congress passed the 1918 Sedition Act.1 This made it a crime to use "disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States." Newspaper editors may have had their own reasons for not reporting on the epidemic, but fear of legal action by the federal government may have topped the list.

By the end of summer, the flu had spread enough that doctors became increasingly worried. For example, in September of 1918, doctors in Philadelphia asked the press to advise the public against attending an upcoming “Liberty Loan” parade. Local papers refused to run the articles. Doctors pleaded with Philadelphia’s public health director to cancel the parade, but their pleas were dismissed. The parade became a super-spreader event. Over the course of the next month, over 12,000 people in the Philadelphia area died from the Spanish Flu.

President Woodrow Wilson didn’t help. Wilson, borrowing a page from the Europeans, chose a combination of censorship and propaganda. This was America’s first real governmental threat to the freedom of the press.2 He demanded “loyalty” from all Americans in the lead up to World War I and his administrations pursuit to “make the world safe for democracy.” Days after Congress declared war in April of 1917, Wilson issued an executive order creating an agency called the Committee on Public Information. It was led by the journalist, George Creel, and was intended to persuade Americans to support the war and recruit soldiers.

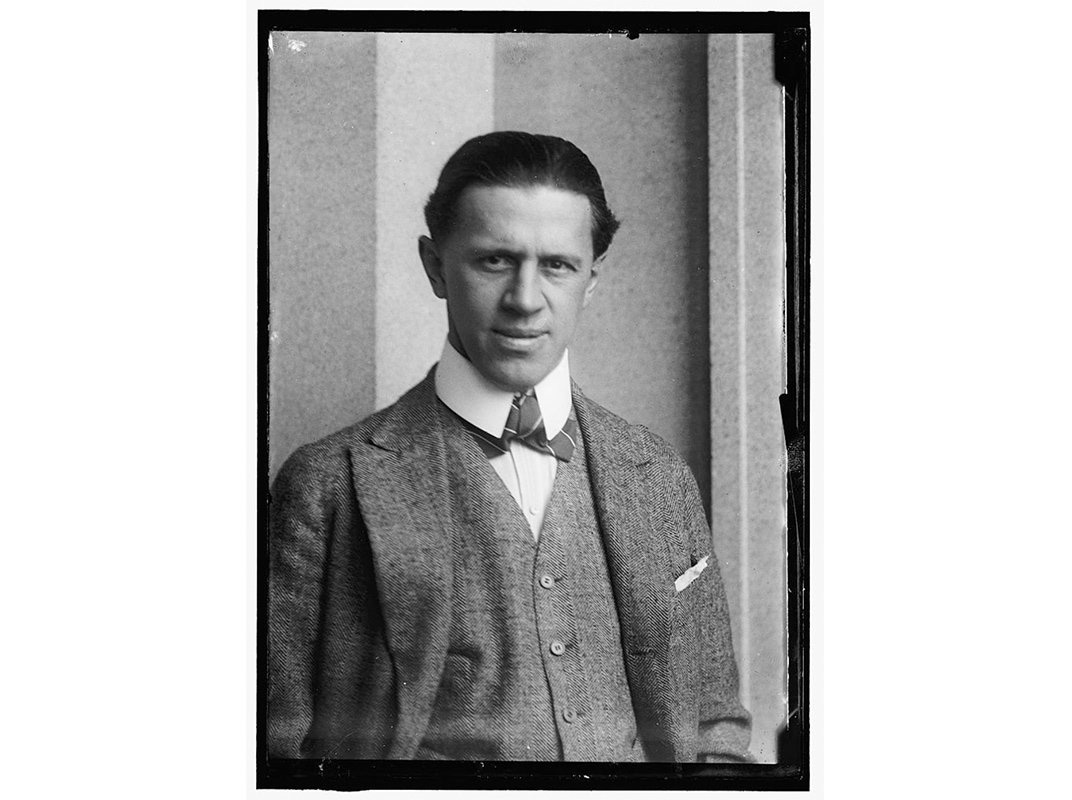

One of the departments was called the Division of Pictorial Publicity and included volunteer artists and illustrators. One of those illustrators was James Montgomery Flagg. Perhaps drawn to patriotism with a name like Flagg, he made one of the most enduring illustrations in American history. It’s the ubiquitous poster of Uncle Sam sternly pointing his finger at the viewer with the face of an angry father, with words in all-caps, “I WANT YOU…FOR THE U.S. ARMY.”

Wilson’s PR man, Creel, was not unlike the over controlling press secretary’s that Trump appointed. Creel demanded the White House only publish good news, flattering reports of the government and the country, and, most of all, propaganda supporting America’s efforts in the war. Mentioning the spread of infectious disease across America did not fit the agenda. Especially when, as in Europe, the bad news included soldiers being infected. Many of whom, were being shipped to Europe where they continued the spread of the virus.

Military doctors pleaded with their superiors and the President to stop sending troops overseas, suspend the draft, and quarantine soldiers. All Wilson was willing to do was temporarily suspend a single draft and reduce the numbers of troops headed to Europe by 15%. By the end of 1918, 45,000 soldiers died from the Spanish Flu.3 That’s just over one-third of 116,000 who died fighting.

In November of 1918, during one of the epidemics largest spikes, the war came to an end. Some believe the Spanish Flu brought World War I to an end. But far be it from any nation’s leaders to admit as much. While Wilson was in Paris in 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference, he came down with a bad case of the Spanish Flu. The White House tried to hide this fact from the public issuing a statement saying the nasty Paris weather had given him a cold.

MASKING REALITY

Not all leaders ignore the advise of medical professionals reporting from the field. Just a few years prior to the Spanish Flu epidemic, in 1910, a plague was ravaging Northern China. All those infected were certain to die within 24-48 hours. In a race with Russia to claim scientific and medical superiority in a cure for the disease, the Chinese Imperial Court assigned a little known doctor, Lien-teh Wu, to head eradication efforts.4

Dr. Wu had discovered through an autopsy that the disease was spread through the air and not by fleas, as suspected. Wu had spent time in Europe as part of his training and observed surgeons using gauze masks during surgery to avoid sneezing or spitting into open wounds. If the mask prevented particulates from escaping the nose and mouth, he thought, perhaps it could prevent them from entering. He began experimenting with his own masks by layering cotton with gauze and fitting the mask close to the face.

But there were skeptics. One was an experienced French doctor who was practicing in China at the time. Dr. Wu explained to the doctor his theory of the plague being spread airborne and that his mask reduced spreading. The Frenchman responded, “What can we expect from a Chinaman?” To prove he was right, the racist doctor visited a hospital housing victims of the plague without Wu’s mask. He died two days later.5

News of the efficacy of Dr. Wu’s invention spread around the world. Mask use was commonplace in the medical profession by the time the Spanish Flu hit. Even ordinary citizens were aware of its effectiveness. While it’s impossible to prove at this point, populations in U.S. that wore masks faired better than those that did not. Seattle was one such city that embraced mask wearing.

But just like today, there were detractors. The same excuses were used one-hundred years ago as we hear today. People complained they couldn’t breath. Others felt it was a challenge to their civil liberties. Businesses worried mandatory mask wearing would hurt business while some thought masks would offer a false sense of security.

San Francisco passed a law mandating mask wearing, but enforcement posed challenges. One over zealous enforcer shot a man who refused to wear a mask. And when a photo emerged of the mayor and other public officials not wearing masks at a boxing match, citizens revolted; especially when they were not charged or assessed fines that ordinary citizens faced. Still, San Francisco stood out as the mandate resulted in a significant decline in cases.

The widespread prevalence of mask wearing in America, and news of San Francisco’s success abating the disease, spread to other parts of the world. Most notably, Japan. In February of 1919 their National Public Health Bureau pushed local health workers to wear masks while tending to flu victims. Later they added guidelines for mask wearing by the public in crowded places like trains and trams. By the fall of 1919 Japan was distributing free masks to those who could not afford them. They then included cinemas and busses to the list of suggested public spaces for mask wearing.6

As the Spanish Flu subsided in America, so did mask wearing in public spaces. But it stuck in Japan, and other East Asian countries, to this day. Maybe we’ll be seeing more of it in the West even after COVID subsides. If it ever does.

As the COVID pandemic unfolded, we witnessed a proverbial passing of the buck as the world searched for answers. The finger pointing started at the origin. Doctors and nurses were put on the spot as people demanded clues as to what it was and how it spread. Western medicine has taught us to view doctors as omniscient beings, fountains of knowledge – surrogate paternal or maternal oracles of comfort. But through three surgical masks and a plastic shield they said, “Don’t look at me, you need to talk to the virologists. Besides, I’m just trying to stay alive myself. Now excuse me, this person can’t breathe.”

The virologists, a bit removed from the mess, summoned their knowledge of microscopic distress. They spoke of gamma phage, viroids, prions, and nano plagues. And when peppered for clarity amidst the hysteria – to get the gist on this viral mist – they pointed to epidemiologists.

These fine folks are the furthest from the pain. People become numbers and points on a plane; Statistical patterns that seek to explain; hints at causation of a transmission chain. But the models they use assume we’re the same. They think we behave like lemmings in a game.

Epidemiologists (as well as virologists and physicians) perform mathematic experiments using a fixed set of variables that assume humans behave, and react, the same across diverse populations. Those assumptions are largely modeled after behavior Western science has been most focused on over the centuries:

WEIRD people.

Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic.

And as we know, even within the WEIRD community, there is a lot of variation in behavior!

When statistical models assume idealized behavior of the so-called, rational man – people who consistently and optimally perform subjective but rational acts – they ignore the fact people do not largely act rationally. This makes it hard to then predict how the virus will behave across diverse sets of populations. Especially when those who do act rationally are randomly exposed to interactions with people who may not act rationally. Human social behavior, especially at the scale that epidemiologists study, can be more random than not.

THE COMPLEX ALTERNATIVE

But there are those seeking to change this. A November 2021 study by a diverse set of researchers, mostly out of the University of Illinois, introduced randomness into the more traditional and relatively inadequate epidemiological models to simulate human social behavior. Instead of using variables that assumed people would act rationally and predictably, they seeded them with a distribution of random numbers that more accurately account for the random interactions we have with people and place.

By capturing multiple features of COVID outbreaks they discovered a “small fraction of individuals were responsible for a disproportionately large number of secondary infections.” Traditional models assumed this would lead to herd immunity. This has not shown to be true even among those areas hardest hit by the first wave. They also discovered another “puzzling aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic.” They observed frequent regional plateaus with an “approximately constant incidence rate over a prolonged time.”

They reasoned it is human behavior that likely causes this pattern. They surmise that what causes “both suppression of the early waves and plateau-like dynamics is that individuals modify their behavior based on information about the current epidemiological situation.” They also suggest these epidemical dynamics of “long plateaus might arise because of the underlying structure of social networks.”

What they claim is happening is local outbreaks cause people to adjust their behavior, either voluntarily, through social pressures, or both commercial and governmental restrictions. When people move less the cases plateau. But as soon as they start trending down, everyone starts moving again. Some of these people, even during the peak, travel to different regions that may be experiencing a slump of outbreaks. A portion of whom are carrying the virus and inadvertently spread the disease creating a new wave of cases in that locale.

These short-term localized waves, and commiserate behavior, repeatedly occur around the world. They create, and perpetuate, persistent long-term waves of the pandemic. These researchers claim these longer-term waves have the potential to stretch out for years given current human behavior.

When the pandemic first started to unfold, the Santa Fe Institute started a podcast series called Transmission. It looked at the pandemic from a Complexity Science perspective. The host, Michael Garfield opens by stating, “The coronavirus pandemic is in one sense a kind of prism: it reveals the many interlocking systems that, until disrupted, formed the mostly invisible backdrop of modern life…” He continued, “The virus acts on, and invites new understanding through, the complexity we only take for granted at our peril.”

The Institute took the transcripts from those episodes, and other Santa Fe Institute reports, studies, and insights from a set of international complexity thinkers, and published them in a recent book titled “The Complex Alternative: Complexity Scientists on the COVID-19 pandemic.” It invites the authors of these early reports to reflect on what they got right and what they didn’t.

Garfield recently interviewed the two editors, the current and former president of the Santa Fe Institute, David Krakauer and Geoffrey West. He had them reflect on the book, but also on what they believe Complexity thinkers got right and where there’s more to be learned.

Krakauer mentions a split in opinions and hints at what is the essence of the study I quoted from before,

“There are those who will say we have to get behavior into the mathematical models. Otherwise they're going to be useless, right? And we've talked about this before; the early phase of infection being quite biological and well-behaved exponentially, and then going nuts with human behavior dominating rather than biology.”

But he goes on to point out that it’s not that mathematicians have thrown in the towel.

“But then there are others who said, no, we just have to find the new course grain models. We just have to be more sophisticated. Drop the deterministic mass action, put the stochasticity [randomness] in, and then we get the causality out. We don't get prediction out, but we get causality out. So there, even the community is internally riven on the question of what the right response should be.”

Near the end, Krakauer concludes by saying, “I think we do not understand how collective intelligence works.” but that over the last two years, “we were all schooled in collective stupidity.” He thinks “we haven't even begun to understand what's going on here” and that we’re “not even in the foothills of understanding how complex reality works.”

Geoffrey West reminds us that “we can't solve these problems unless we have everybody together.” And he’s not just talking about the scientific community, he includes “society in terms of the shakers and movers [like policy makers] who are thinking about these problems from a completely different, and usually non-scientific viewpoint.”

I sit here in Kirkland on this inauspicious anniversary and reflect on my non-scientific point of view. Sadly, what the virus of multae coronae has taught me is this: Fere libenter homines id quod volunt credunt. That’s Latin for “Generally people believe what they want.” But beliefs, like viruses and mask wearing adherence, has the potential to change locally in the short-term while spreading globally in the long-term.

Becky Little. 2020.

Ibid.

Ibid.