Hello Interactors,

Behind every map is intent. When it comes to making plans for a city, streets are more than mere passageways; they are the cartography of power, exacting politics and ideology for the unfolding of urbanity.

Paris is the blueprint of social order and control portrayed as a symbol of beauty and progress. I wanted to unravel the threads of intent, from communal aspirations to the heavy hand of authoritarianism — a kind of narrative map of a city renowned as much for its revolutions as for its romance.

Let’s go.

COMMON ROOTS, CONTRASTING COMMUNITIES

I’ll offer a word and you examine your emotional reaction to it. Communism. If you’re like me, you’ve been trained to have negative thoughts. Maybe even stop reading. Communism has been associated with authoritarian, repressive regimes that denied basic freedoms and human rights. Ask anyone who lived under these conditions and you can see why it’s been ideologically blackballed in America.

Now I’ll offer another word. Community. Ah, yes, good vibes. Who could possibly be against community? It’s strange how two words with common origins can differ so much by changing two letters.

The word Communism comes from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel’s Kommunismus as early as 1847 and is derived from the French word communisme which first appeared three years earlier in 1843. This word comes from the Old French word comun meaning "common, general, free, open, public."

A group of people in common, “the common people” who are not rulers of property, clergy, or monarchy, is from the 14th century French word comunité meaning "commonness, everybody" or community.

I had the experience of checking my own reaction to the word communist while reading about how communist ideals helped a politician in Paris help his community.

The French Communist senator, Ian Brossat, lead housing policy in Paris for a decade. He said his

“guiding philosophy is that those who produce the riches of the city must have the right to live in it.”1

He and the local government under Mayor Hildago are doing their best to live up to this. Over the past decade, the French Communist Party has emphasized social justice and economic equality, advocating for stronger public services, wealth redistribution, and workers' rights. They've also focused on environmental sustainability, aligning with broader movements to address climate change and social disparities.

People from all over the world are drawn to Paris for its diverse array of small shops, cafes, expansive boulevards, monuments, and museums. It exudes old-world charm complete with cobblers, tailors, jewelers, and luthiers tucked in and among various neighborhoods — some more manicured than others. It’s a dappled array of diverse color and verdant softscapes that when viewed from afar offers an impression of a picture-perfect pointillist painting.

Paris exists as a seemingly organic and emergent unfolding of placemaking complete with public spaces and parks for the taking — by all walks of life. For many, it’s a composite of ideals that harken back to romantic images of a fashionable and stylistic ‘pick your favorite’ century in Europe making it a perennial favorite destination for tourists.

But surrounding the parks where healthy blossoms glow are stealthy property plots where wealthy funds grow. Amidst the green where healthy plants are planted longtime residents squirm as their neighbors are supplanted. Despite the city building or renovating “more than 82,000 apartments over the past three decades for families with children”, 2.4 million people are on the waiting list for affordable housing.(1)

This isn’t the first time economically disadvantaged people have been displaced from Paris. In 1853, one year after Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew Napoleon III declared himself emperor in a successful coup d'état, he wasted no time embarking on what many believe to be the biggest ‘urban renewal’ project in history.

It was famously led by a former prefect administrator, Georges-Eugène Haussmann. His swift and heavy hand pushed powerless Parisians to the periphery to build the Paris so many adore, only to have them return. A pattern that exists today.

Napoleon III, exiled in England, was reluctant to return to a France in decline, marred by unemployment and poverty. By 1848, a massive influx of laborers had swollen Paris's population to over a million. Despite its picturesque image today, 19th-century Paris was a labyrinth of dilapidated buildings and narrow streets, lacking modern infrastructure, and grappling with increasing crime and deadly outbreaks, including a cholera epidemic that claimed 20,000 lives in 1832.

The French author Honoré de Balzac wrote of Paris at the time,

“’Look around you’ as you ‘make your way through that huge stucco cage, that human beehive with black runnels marking its sections, and follow the ramifications of the idea which moves, stirs and ferments inside it.’”2

By 1848, France was besieged by societal strife as the monarchy's resurgence fueled public outrage, contrary to the Republic's ideals of liberty. Mass protests and strikes became common, culminating in a tragic clash at the Foreign Ministry where troops fired on protestors, killing 50. The slain were symbolically paraded through Paris, highlighting the oppressive turn of events.

This ignited the Revolution of 1848; a diverse coalition, from students to disillusioned aristocrats, took to the streets, overwhelming the army and storming the King's palace. This mass uprising prompted the formation of a provisional government while monarchist officials, including Haussmann, fled the turmoil.

In the power struggles of post-revolutionary France, neither Socialists nor Republicans could stabilize the economy or improve living conditions. As a result, calls for Napoleon III's return gained traction. He pledged to serve if elected, mirroring the American democratic elections model. He won a four-year term by a wide margin, but he did not have dominant support within the Assembly.

Facing political opposition and public discontent as his term ended, Napoleon III dissolved the Assembly, fired his adversaries, and named himself emperor. A government for the people and by the people was attempted and failed. Long live the King. Authoritarianism was back to the cheers of many in the streets as Napoleon was pulled through the streets by carriage for three hours amidst roars of support.

PARIS: FROM SIEGE TO CHIC

By 1848, Parisians had erected numerous barricades, limiting Napoleon’s access through the city. Originating in 1588 as a defense against soldiers, these barricades evolved from rudimentary stone walls into complex structures capable of withstanding cannon fire, serving both practical and symbolic roles in the city’s history of civil resistance.

Amidst the dawn of the Industrial Age in 1848, Napoleon III aimed to modernize Paris, differentiating it from the neo-gothic style of London's "Albertropolis." Preferring the era's new materials like iron and glass. Dismissing the gothic aesthetics, Napoleon, with Haussmann—a disciplined administrator with similar architectural sensibilities—set out to reshape Paris into a contemporary urban jewel.

In the words of Hausmann reflecting in his memoir,

“We ripped open the belly of old Paris, the neighborhood of revolt and barricades, and cut a large opening through the most impenetrable maze of alleys, piece by piece.”3

In Balzac’s 1843 book Lost Illusions he captures the contrasting existence of society revealing the class Hausmann sought to favor at the expense of the other.

The proletariat

“live in insalubrious offices, pestilential courtrooms, small chambers with barred windows, spend their day weighed down by the weight of their affairs.” While the bourgeoisie enjoy “the great, airy, gilded salons, the mansions enclosed in gardens, the world of the rich, leisured, happy, moneyed people.”(2)

Haussmann, satirically termed the "Artiste Démolisseur," enacted a policy akin to 'creative destruction' to achieve it. This is a concept Karl Marx alluded to and the Austrian Economist Joseph Schumpeter later popularized. In Marx and Friedrich Engels popular 1848 book “The Communist Manifesto” they used the term Vernichtung which describes the continuous devaluation of existing wealth to pave the way for the creation of new wealth.

During the 1830s and '40s, monumental ‘devaluations’ came at the expense of land and rivers paving the way for infrastructure like railroads and canals. Including other parts of the world. Americans, Indigenous and colonized, saw over 3000 miles of canals being dug by 1840 and 9,000 miles of railroad by 1850. We can all think of examples of ‘creative destruction’ today — be it from bombs that fall or a wrecking ball.

This 19th century period of transformation also saw France's first passenger train and the spread of a national railway network, all under Napoleon III's ambition to fortify France's economic stature. He promoted and founded new national banks to fund these transformations, fueling Marx's view that economic efficiencies could be gained through improved transportation.

The rise of capitalism and the concept of 'the world market,' as Marx termed it, pushed for more efficient movement of people and goods, a task complicated by Paris's antiquated layout. Although Napoleon and Haussmann are credited with modernizing Paris, initiatives to improve urban circulation were already underway. Prior to 1833, significant canals, roads, and railways were constructed, and post-1832 cholera outbreak, efforts were made to expand the city and reduce congestion.

Architectural and urban planning, including the design of the Place de la Concorde by Jacques Hittorff, aimed to push the city's boundaries. In 1843, Hippolyte Meynadier proposed major urban changes to improve air quality and circulation. Haussmann later embraced and amplified these existing plans with and without Napoleon's support. For example, Napoleon did not see the need to bringing running water to Paris, but Hausmann did it anyway.

Hausmann was fond of expanding. Whereas these earlier plans were certainly grander than any in Paris, or possibly the world, Hausmann multiplied dimensions. Hittorf had drawn plans for some streets be obesely wide, even by today’s standards, but Haussmann tripled the dimensions. For example, the road leading to the Arc de Triomphe, known now as the Champs-Élysées, was first drawn to be 120 feet wide. But Hausmann insisted it be 360 feet wide with an additional 40 feet of sidewalks on each side. He tripled the scale of a project that had already been tripled.

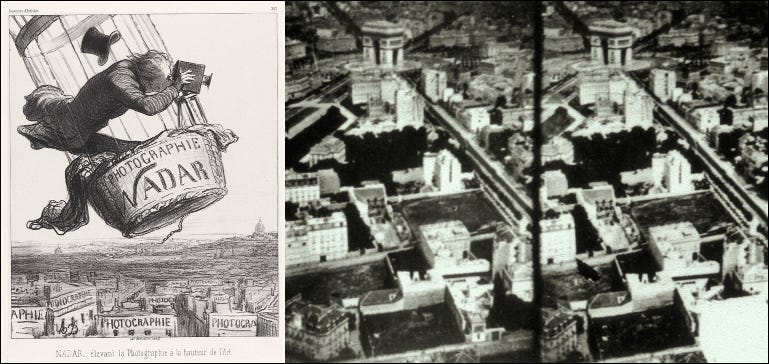

What resulted was a diagonally criss-crossing web of stick straight boulevards with massive monuments strategically placed at nodes and termini. The Arc de Triomphe from above looks like a shining star with roads and boulevards as glimmering spires. Some scholars believe Hausmann, and his coconspirators, were the first to view the city as a technical problem to be solved from the top down.

It was a civic product to be worked on with little regard for the people who were working within. This view of a city may have been influenced by the aerial photographer Nadar who from 1855 to 1858 perfected aerial photography in France. He patented the use of aerial photography for mapmaking and surveying in 1855.

A WHOPPER OF A TRANSFORMATION

Soon after Hausmann finished the complete remaking of Paris in 1870, Friederic Engels published his 1872 book The Housing Question where he explored the housing crisis facing industrial workers of the 19th century. He criticized what became known as the Hausmannization of cities, writing,

“By ‘Haussmann’ I mean the practice which has now become general of making breaches in the working class quarters of our big towns, and particularly in those which are centrally situated, quite apart from whether this is done from considerations of public health and for beautifying the town, or owing to the demand for big centrally situated business premises, or owing to traffic requirements, such as the laying down of railways, streets, etc. No matter how different the reasons may be, the result is everywhere the same: the scandalous alleys and lanes disappear to the accompaniment of lavish self-praise from the bourgeoisie on account of this tremendous success, but they appear again immediately somewhere else and often in the immediate neighbourhood”4

Groups of people struggling to live in a city, “the common people”, those who were not rulers of property, clergy, or monarchy, began organizing as a community. Property owners spared by Hausmann’s utter destruction saw their applications for building improvement permits rejected. In the years leading up to 1871, tensions were once again mounting in a city that had yet to form a municipal government.

Meanwhile the Francho-Prussian War erupted in July of 1870 as France sought to assert its dominance in Europe fearing a pending alliance between Prussia and Spain. During the war, the French National Guard defended Paris. Given their proximity to growing working-class radicalism, sentiments began to be shared among soldiers.

After a significant defeat of the French Army by the Germans, National Guard soldiers seized control of the city on March 18, killing two French army generals and refusing to accept the authority of the French national government. The community became a commune — common, general, free, open, and public.

The commune governed Paris for two months, establishing policies that tended toward a progressive, anti-religious system of their own self-styled socialism. These policies included the separation of church and state, self-policing, the remission of rent, the abolition of child labor, and the right of employees to take over an enterprise deserted by its owner.

Predictably, the Commune was ultimately suppressed by the national French Army at the end of May during "The Bloody Week” when an estimated 10-15,000 Communards were killed in battle or executed.

The Commune's policies and outcome had a significant influence on the ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who described it as the first example of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Without it, it’s unlikely Ian Brossat would have a Communist party fighting for fair living conditions. A modern day nod to those Communards slaughtered in 1871.

Meanwhile, today’s City Hall also ensures the persistence of the bucolic, romantic, idealistic — and perhaps classist — proprietors who help to sustain the manicured experience Hausmann set out to achieve nearly 200 years ago. Just as the government plays a role in controlling rent so less financially privileged can live and work there, so too does the government subsidize select city shops and restaurants that attract the well heeled. But they have their limits.

The counselor in charge of managing commercial holdings said, “We don’t rent to McDonald’s, we don’t rent to Burger King and we don’t rent to Sephora.”

These stores obviously exist, so clearly landlords across the city have long sold out to ‘world market’ chains even Hausmann may frown upon. Even as the city take steps to ensure curated theme shops continue to exist. Hausmann may not have planned for this, but Paris did become a kind of a public theme park to the world.

Given the history of radicals and conservatives toiling in a tug of war for centuries over what exactly the city should be and for whom, perhaps the conservative former housing minister now commercial developer, Benoist Apparu, put it best —

“A city, if it’s only made up of poor people, is a disaster. And if it’s only made up of rich people, it’s not much better.” (1)

I, for one, was pleased to find a Burger King on the Champs-Élysées during my first trip to Paris as a teenager in 1984. After a few days of European food, I was ready for a Whopper. Of course, I was unaware of any of the socio-political or psychogeographical implications and ramifications of all this — both historically and in that moment.

I was a middle-class mini-bougie white American eating comfort food while obliviously participating in the exploitive world of ‘rich, leisured, happy, and moneyed people’ on a boulevard designed for it. But I was also in city that birthed liberty, the potential for revolutionary change, and the promise and struggle of egalitarian policies.

How Does Paris Stay Paris? By Pouring Billions Into Public Housing. Thomas Fuller. New York Times. 2024.

Paris, Capital of Modernity. David Harvey. Routledge. 2003.

The Geography of Capitalist Accumulation: A Reconstruction of the Marxist Theory. David Harvey. 1975. Wiley Online.

Paris, Haussmann and property owners (1853 – 1860): researching temporally distant events. Antoine Paccoud. London School of Economics and Political Science. 2013.