Hello Interactors,

Most people think roads were planned, designed, and built for cars, but that’s not true. They’re public spaces intended to bring social and economic benefit by increasing mobility. Economically they’re successful, but socially they not only are failing us…they’re killing us.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

WALKING AND BIKING TO DEATH

Today is “Bike Everywhere Day” in the Seattle area. Once known as “Bike to Work Day”, it would typically inspire an estimated 20,000 people to grease the chain, pump up the tires, strap on the helmet, and tepidly merge into the smooth, rolling polluted river of concrete nestling up alongside menacing machines of masculinity hastily rushing to work. Commuting patterns have been disrupted by Covid the last couple years. But with the League of American Bicyclists declaring May as “Bike Everywhere Month” commuting to and from work isn’t the only reason to slide onto the saddle. If you dare to do so.

According to the CDC, “bicycle trips make up only 1% of all trips in the United States. However, bicyclists account for over 2% of people who die in a crash involving a motor vehicle on our nation’s roads.” It’s important to note the CDC use the human-centered word ‘bicyclist’ to describe the victim but an object-oriented word ‘motor vehicle’ to describe the killer. It’s not the motor vehicle’s fault these people died, it’s the fault of motorists. As gun enthusiasts like to remind us, ‘guns don’t kill people, people do.’ The same is true for cars and both machines can be violent killers. The CDC report “Nearly 1,000 bicyclists dying and over 130,000 injured in crashes that occur on roads in the United States every year.” But that’s only those reported. Most cyclists, especially in disadvantaged communities, don’t bother reporting crashes. And not all police nor hospitals report or rate car-related bike and pedestrian injuries consistently…if at all. And different sources report different numbers.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission reports “425,910 emergency department-treated injuries associated with bicycles and bicycle accessories in 2020.” The National Highway Traffic Safety Administrations reports “932 bicyclists were killed in motor-vehicle traffic crashes in 2020, an 8.9% increase from 856 in 2019.” The U.S. Department of Transportation announced this week that 43,000 people died on roadways in 2021 – the highest since tracking began in 1975.

That’s a 10% percent increase over 2020. Pedestrian fatalities were up 13% and bicycle fatalities were up 5%. They note that during Covid speeding offenses climbed causing a 17% increase in speed-related fatalities between 2019 and 2020 and a 5% increase prior to 2019. It’s unclear how speed factors in the increase in pedestrian and bicyclist deaths during this time, but there is no denying that speed kills.

The Transport Research Laboratory out of the UK compared multiple datasets of ‘pedestrians killed’ by the ‘front of a car’ (again comparing people to an object) to better understand the relationship between speed and risk of fatal injury to pedestrians. They concluded

“The risk increases slowly until impact speeds of around 30 mph. Above this speed, risk increases rapidly – the increase is between 3.5 and 5.5 times from 30 mph to 40 mph.”

This applies to cyclists as well. Choosing to bike on roads in America comes with a risk of dying that is nearly five times greater than choosing to drive a car. And the odds of dying in a car accident are already relatively high – 1 in 101 – the eighth largest risk just behind suicide and opioids in 2020.

The ugly truth is the ongoing and rising deaths and injuries to cyclists and pedestrians at the hands of motorists is a seemingly necessary cost to uphold the freedom, comfort, and convenience of automobility that many enjoy. Our political and public administrative services care about saving lives, but evidently not if it means changing road designs, land-use policies, travel patterns, restricting access to some roads, or – heaven forbid – creating viable ways to ditch the car should you choose.

But this country did once care about saving lives on the road. As the post-WWII boom in cars and roads continued to balloon so did car-related deaths. Federal, state, and local governments rallied to make cars and roads safe for motorists. The same is true for new bikes purchased for baby boomers. When kids were getting injured and killed on their bikes in the 60s and 70s due to poor design and construction, consumer protection agencies cracked down on manufacturers and the federal government almost made it illegal to bike on the street.

It was a bike enthusiast out of Davis, California, John Forester, who fought for a cyclist’s right to use public roads. But as a confident cyclist, and self-proclaimed engineering expert, who prided himself on his ability to ride in traffic, he advocated for ‘vehicular cycling’ which meant treating a cyclist more like a motorist than a pedestrian. He even claimed protected or separated bike lanes were more dangerous than riding with traffic. He was making that claim up until he died in 2020.

But he mostly was a bike snob who didn’t want to be burdened with having to share space with kids and slower everyday cyclists on a bike path, so he made it his lifelong ambition to tank efforts to build safer bike infrastructure. Though, it was elite bicycle enthusiasts like him we have to thank for the existence of paved American roads in the first place.

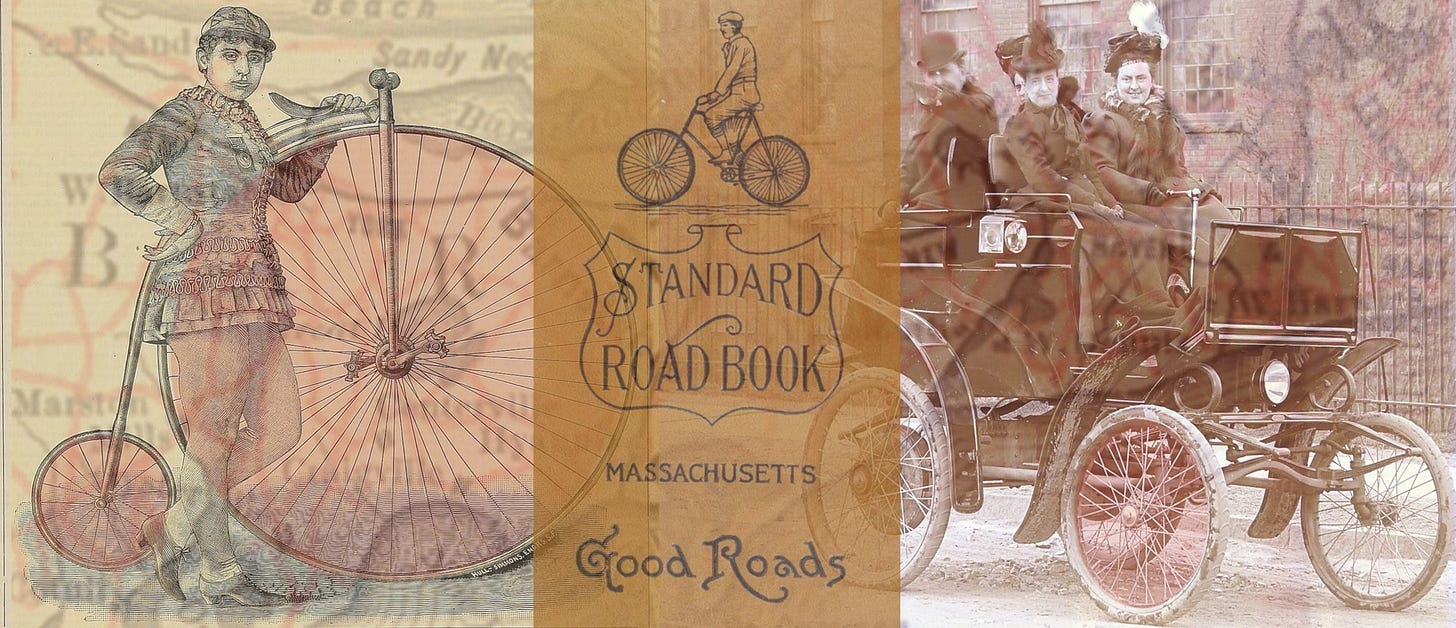

A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN

“Every person has an equal right to travel on the highways, either on foot or with his own conveyance, team, or vehicle. This right is older than our constitutions and statutes … The supreme rule of the road is, Thou shalt use it so as to interfere as little as possible with the equal right of every other person to use it at the same time …”1

This was written in 1897 by a patent attorney named Charles Pratt. He was one of three men who started the League of American Wheelman (L.A.W) in 1880. Now called the League of American Bicyclists, they’re the leading sponsor of today’s “Bike Everywhere Day.” Pratt was joined by a bike importer, Frank Weston, and writer, adventurer, conservationist, Kirk Munroe. Together they grew the L.A.W. to become one of the most influential and powerful organizations of their time. They are also the originators of America’s paved roads.

In 1888 the L.A.W. members voted to fund the National Committee for Highway Improvement. Their first publication served as a textbook for road construction called, Making and Mending Good Roads & Nature and Use of Asphalt for Paving. Fifteen-thousand copies were printed and sent to state legislators as well as county, city, and town officials. But they also solicited bike manufacturers and dealers, road construction and pavement companies, and equipment manufacturers. Asphalt and pavement companies eagerly offered their support and financial contributions to the effort.

One of the members of the L.A.W., Civil War Colonel and bicycle manufacturer (who later made electric cars), Albert Pope, was one of the most eager supporters of what became the ‘Good Roads Movement.’ In 1889 he offered an upfront contribution of $350 with an offer to fund whatever was necessary to build good roads writing: “Go ahead with the work…and we will pay the whole or any part of the expense you desire.” 2

If this sounds like a bunch of wealthy cycle enthusiasts coming together to design, fund, and build public roads across America, it is. Recall this is the same model used to build the rail system across the United States in the 1840s. Federal or state funding, or government sponsorship of any public transportation, was not on the minds of elite power brokers of the 19th century…or the 18th century for that matter. Road and highway design, construction, and maintenance was believed to be the job of local governments in partnership with private parties. One L.A.W. member from New York, A.J. Shriver, wrote in 1889 that federal funding of roads was “Socialistic” and thereby “unconstitutional.”3

But these beliefs and attitudes were largely coming from wealthy urban elites. Bicycling, after all, was something the privileged class enjoyed as a kind of hobby. But in the rural countryside attitudes were different. Most farmers were responsible for maintaining the roads along their property and believed they ‘owned’ them. They were also leery of wealthy city-slickers offering opinions on how ‘their’ roads were to be designed, used, and by whom.

The L.A.W. drafted legislation in 1889 calling for a state tax to fund the highway commission for the creation of maps and plans for the construction of ‘good roads.’ The legislation was adopted by nine states, but failed to garner the necessary votes. Farmers were speaking out against this infringement on ‘their’ property. One Michigan farming coalition wrote, “The farmers must bear the expense while bicyclists and pleasure-riding citizens will reap the larger benefits.”4

The defeats at the state level sent the L.A.W. back to the drawing board. They realized they needed a different approach. Their president wrote, “We must concentrate first on education, then agitation, and finally legislation.” They created a monthly publication that was an “Illustrated Monthly Magazine Devoted to the Public Roads and Streets” that hit a peak circulation of 75,000 copies by 1895.

In 1898 the L.A.W. then published a 41-page book titled, Must the Farmer Pay for Good Roads?. They mailed 300,000 copies to farmers and members of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It worked. The book’s author, Otto Dorner, later wrote in The Forum magazine that,

“… the farmers of the United States are beginning to thoroughly appreciate the need [for] better highways; and the work of the League of American Wheelmen in the direction of State aid is receiving much support from the more progressive among them … The Farmers’ National Congress … [commended] the efforts of the League of American Wheelmen to bring about the general introduction of the State Aid system.”

The Model T was just around the corner, but it was the bicycle and bicyclists that made that corner. In 1902 these words appeared in a magazine called The Automobile:

“The effect of the bicycle on road improvement has been … phenomenal in the past 10 and 15 years …” …Directly and indirectly the bicycle has been the means of interesting capital in road building to the extent of millions of dollars, and of spreading abroad more accurate and scientific data concerning road construction than was ever before done in so short a time. The bicycle practically paved the way for automobiling.”

IT'S ONLY FAIR

Cyclists today get little gratitude for the early lobbying efforts to build smooth, safe roads. But it should also be noted that these early wealthy and influential cycling enthusiasts quickly became motoring enthusiasts. Henry Ford tends to get all the credit for automobile manufacturing, but it was the early bicycle manufacturers who converted bike factories to car factories. Henry Martyn Leland, before he created Cadillac and Lincoln, was making bike transmission parts for Colonel Pope’s bike company. A car, after all, is just a glorified motorized quad-cycle.

Men like these are often portrayed as the protagonist in the power and glory of the early story of bikes, but women rode too. And it wasn’t just high-society women biking either. In 1872, Louise Armaindo, set the American long-distance record, covering more than 600 miles in 72 hours. In 1890, Kittie Knox became the first African American woman to become a member of the League of American Wheelman. She didn’t stop there. She became a successful bike racer and became the first woman to be seen racing in ‘bloomers’ instead of a skirt. Sadly, she still faced fierce discrimination. And while the bicycle plays a huge role in the liberation of women, and a symbol of the suffrage movement, women are still fighting for recognition, acceptance, and necessary leadership opportunities in a the current burgeoning cycling movement. They are also unrepresented in determining the design and use of our roads.

Not much has changed since the 19th century. The design of motorized and non-motorized vehicles, and the transportation infrastructure they require, is still very much dominated by Western, mostly white, men. Just as those early bicycle and pavement businessmen came together around the L.A.W. to “organise capital accumulation, advanc[e] elite entrepreneurial agendas, and consolidat[e] urban regimes”, so too are today’s, mostly white male, CEOs of automobile, oil and gas, chemical, concrete and asphalt, and road construction companies.

And they’re all in collusion with legions of civil engineers, elected officials, and administrative workers at the federal, state, and local level to provide a transportation system that perpetuates our insatiable need to make more money to buy more things; this requires more roads to move more people and more things by car or truck; which in turn creates more waste, more pollution, and more traffic-related deaths.

This approach to planning public land has led to uneven urban and suburban development, perpetuated ethnic and race privilege, and is rooted in attitudes and beliefs stemming from a culture of patriarchy. As a group of transportation researchers out of Belgium observe,

“…how across strikingly diverse cities, urban regimes hide and legitimize these logics by applying the discourse of sustainability, framing infrastructural investment as a largely technical and rational response to the problems of congestion or low quality of public space. Instead, approached critically, transport is an essentially political issue of distributing social and spatial benefits and costs of urban development.”

That’s from their February 2022 paper, Moving past sustainable transport studies: Towards a critical perspective on urban transport. They call for a critical assessment of the study of transportation, adding that such a “perspective departs from analysing and juxtaposing specific transport modes (e.g. airplanes and private cars against public transport) and related lifestyles (e.g. mass tourism, suburban life and work against cycling and walking), and instead demonstrates their role in sustaining socio-economic structures that enable the capitalist mode of producing urban space and society. Therefore, in sum, being critical about transport means analysing it as a key component of capitalism.”

They go on to prove their point by querying existing transportation research for terms like “capitalism” or “capitalist”, “neoliberalism”, “feminism”, and “race” and find there are few results. The words “equity” or “equality”, and “gender” return just 2% of existing publications found in the hundreds of thousands of leading academic transportation and mobility journals. In the larger corpus of over six million Social Science publications the percentage of reports with those three words doubles to 4%.

They also point out “unravelling and analysing power and ideology underpinned and reproduced by transport in urban settings is by no means an exercise that hinges on a particular theoretical lens (Marxist, anarchist, feminist etc.) or focuses on a specific social group or factor (class, gender, ethnicity and race, age). But they nonetheless remind us that any critique of a system that has led to a climate-crisis and obscene income disparities has to be grounded in some social theory “because investigated facts are the result of human actions displayed within a given society.”

Only with this analytical lens, they write, will we be able to “rais[e] the fundamental question of whether the role of public transport is to provide a public service to its passengers, or rather to generate profits for its shareholders.” We should also raise the question of whether we want to continue to use public land in the form of streets to be a place where too many people fear they will die or become injured. Is that a necessary price for our social system?

Richard Van Deusen, an interdisciplinary researcher of the interaction of people and place writes: “Public space must be understood as a gauge of the regimes of justice extant at any particular moment.”

Is the comfort, convenience, and luxury of car-oriented travel patterns worth interrupting in the interest of improving the lives we live, the air we breath, and the water we drink? And for all those who are forced to live where a car is needed to earn a living wage, or those with impairments, where are the plans for fair, equitable, and just transportation and/or housing alternatives?

When the freedom to choose comes with nothing to lose, the costs of social and spatial benefits diffuse. Escape the snare, get out in the air, let’s make our roads more fair. Equitable places in our public spaces means biking and walking everywhere. That may sound utopian, but as Geographer Don Mitchell once wrote,

“Utopia is impossible, but the ongoing struggle toward it is not.”

Roads Were Not Built for Cars: How cyclists were the first to push for good roads & became the pioneers of motoring. Carlton Reid. Island Press.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.