Hello Interactors,

Today is Black Friday. It’s one of the most anticipated shopping days of the year. In Part 1 of this two part series, I talked about how the Christmas holiday season is rooted in consumption and classism. Its origins had little to nothing to do with Christianity, but everything to do with establishing social order. Black Friday is no different.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

VISIONS OF SUGAR-PLUMS DANCED IN THEIR HEADS

American colonial settlers debated Christmas celebrations well in the 1700s. Bouts of drunken caroling, groveling, and fallacious philia raged from harvest season’s end through December. While the practice was as old as the Roman Saturnalia, Puritan settlers hoped to sever the European connection.

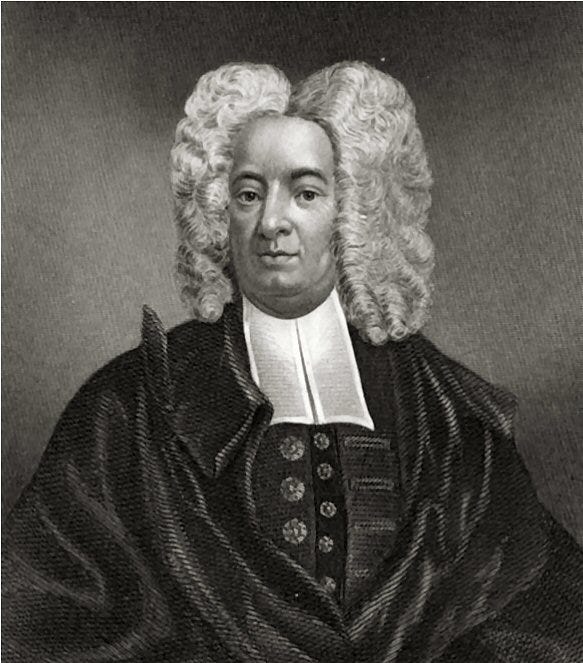

One Puritan, Reverend Increase Mather, “accurately observed in 1687 that the early Christians who first observed the Nativity on December 25 did not do so ‘thinking that Christ was born in that Month, but because the Heathens Saturnalia was at that time kept in Rome, and they were willing to have those Pagan Holidays metamorphosed into Christian [ones].’”

The harvest parties only increased until the colonists overthrew England’s Dominion of New England in 1689. One Connecticut almanac producer, John Tully, wrote in 1688,

“The Nights are still cold and long, which may cause great Conjunction betwixt the Male and Female Planets of our sublunary Orb, the effects whereof may be seen about nine months after…”

Tully also bravely printed Christmas Day on the 25th alongside his weather predictions.

There was not another mention of Christmas until 1711 when Increase Mather’s son, Reverend Cotton Mather (who applauded Indigenous massacres because they “brought Indian souls to hell”) wrote in his December 30th diary,

“I hear of a number of young people of both sexes, belonging, many of them, to my flock, who have had on the Christmas-night, this last week, a Frolick, a revelling feast, and Ball [i.e., dance].…”

The following year, around Christmas time, he preached from the Bible criticisms of faux Christians who used religion to veil ungodly sexual acts, “‘giving themselves over to fornication’—'ungodly men, turning the grace of our God into lasciviousness.’”

Despite Mather’s routine attempts to curb young people’s desire to turn religious events into parties, such at weddings or Sunday night revelry, it only increased. Population data from this time period shows a marked increase in unwed pregnancies. Records show seven month old marriages that featured an addition to the family a couple months later. Also, there’s a notable swelling of births roughly nine months after Christmas. That’s when I was born.

By the early 1700s, Cotton Mather gave up. He reluctantly accepted that Christians could be both Christmas revelers and Christian reckoners; a weakening of Puritanism and a concession his father surely would have admonished. But it set the stage for moderation as evidenced in Benjamin Franklin’s older brother, James Franklin’s, 1733 couplet:

“Now drink good Liquor, but not so, / That thou canst neither stand nor go.”

James was the one who trained young Ben to become a printer. Benjamin Franklin is also remembered as the nation’s model of self-restraint, but perhaps less so as a philanderer. He fathered an illegitimate child before entering a common-law marriage with his housekeeper’s daughter. Perhaps his rustles in the sheets started with a little wassail in streets.

In December of 1734, Franklin wrote this in his second edition of his famed Poor Richard’s Almanac:

“If you wou’d have Guests merry with your Cheer, / Be so yourself, or so at least appear.”

Then again five years later:

“O blessed Season! lov’d by Saints and Sinners, / For long Devotions, or for longer Dinners.”

What Benjamin Franklin, and prolific almanac producer Nathanial Ames, aimed to do throughout the 1700s was to cast Christmas, through printed word, as a time to be merry – but in moderation. Slowly, by the late 1700s, Christmas carols began sneaking into America’s first printed hymnals. The Christmas celebration had finally made piece with Christianity. The Universalists were the first to hold a December 25th service in 1789.

CLOTHES WERE ALL TARNISHED WITH ASHES AND SOOT

But the dawn of a new century, and the industrial age, brought a shift in attitudes around Christmas. The elite, again, distanced themselves from the occasion. As urban cities grew and jobs shifted from the farm to the factory, winter brought new dynamics to the onset of the season. Some factories closed in the cold months as did shipyards along frozen waters.

This brought unemployment and idle time to laborers. Whereas historically wealthy farm owners were willing to amuse the working class in a societal roll reversal – through transient and theatrical wassailing – the urban elite power structures were unwilling to participate. But it didn’t stop the working class from venting.

The once faint mockery of their employers – imbued with subtle hints of revenge should they not offer them gifts, food, or alcohol – turned fierce and riotous in the 1800s. Papers in both England and the United States barely mention Christmas at all between 1800 and 1820. But that was about to change.

In the first decade of 1800, one of New York’s most influential men, John Pintard, became particularly peeved by the seasonal banditti. He reminisced on ‘better days’ when the rich and the poor got drunk together. And while he wished his wealthy friends reveled more among themselves, he grew concerned that “the beastly vice of drunkenness among the lower laboring classes is growing to a frightful excess…”

And in a familiar tone, echoed to this day by many, he feared “thefts, incendiaries, and murders—which prevail—all arise from this source.” Which is why he helped create the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism. This was an organization that sought to curb money directed at care for the poor, but to also stop them from begging and drinking. The white elite ruling class of the 1820s –- as well as many in the 2020s – complained of what one New York paper described as, “[t]he assembling of Negroes, servants, boys and other disorderly persons, in noisy companies in the streets, where they spend the time in gaming, drunkenness, quarreling, swearing, etc., to the great disturbance of the neighborhood.”

Pintard was also hopelessly nostalgic. He founded the New York Historical Society in 1804 and was instrumental in establishing Washington’s Birthday, the Fourth of July, and Columbus Day as national holidays. Pintard also introduced America’s icon of nostalgia, Santa Claus. Seeking a patron saint for the New York Historical Society, and for all of New York City, he commissioned an illustration to be painted of St. Nicholas giving presents to children. While the icon was not intended to be seasonal, it was nonetheless printed on December 6th, St. Nicholas Day, in 1810.

He pined for the days when the rich and powerful could rule over what was becoming a burgeoning working class. In 1822, as Jefferson had just passed a law allowing non-property owners to vote, Pintard wrote to his daughter,

“All power is to be given, by the right of universal suffrage, to a mass of people, especially in this city, which has no stake in society. It is easier to raise a mob than to quell it, and we shall hereafter be governed by rank democracy.… Alas that the proud state of New York should be engulfed in the abyss of ruin.”

WHAT TO MY WONDERING EYES SHOULD APPEAR

1822 was also the year his friend, and wealthy land owner, Clement Clark Moore, wrote what was to become the most influential Christmas poem ever: “A Visit from St. Nicholas” or as it is known today, “T’was The Night Before Christmas.”

This single poem, written for the elite upper class, encapsulates the nostalgia of wassailing Pintard and his friends pined for, while making themselves feel good about themselves for ‘giving to the needy.’ Moore did this by substituting the unruly lower working class, begging for gifts from their master, with children expecting presents on Christmas morning.

He kept the gift giving mysticism of the centuries old St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, but removed the judgmental elements of a Bishop who may make them feel guilty for maintaining class divide by making him “merry”, “droll”, “rosy”, and “plump.” He also made him a lower class “peddler”. And while Santa made a loud noise “on the lawn” with a “clatter”, just as a lower class wassailer would have, he was but a small and unthreatening “right jolly old elf” who kindly left toys he had labored over for the children.

And he asked nothing in return. With a “wink of his eye” and a “finger aside his nose” (a gesture meaning “just between you and me”) Moore gave the privileged class, who were fearful of home invasions at Christmas time, assurance they “had nothing to dread.” All they needed to do, was keep their wealth within the family and buy their kids and friends gifts at Christmas time. Forget the poor, they thought, they’re as hopeless as democracy.

The vision and version of Christmas and Santa Claus that Moore provided his haughty affluent peers, in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, was soon to be read by a growing middle class and an increasingly literate lower class. That’s as true then as it is today.

And while Moore was a country squire who never worked a day in his life, and hated the gridding up of property in a growing New York City, he grew to love the money he earned selling off family property he inherited. Geographer Simeon DeWitt was chopping Manhattan into a Roman style grid to make room for a population that grew from 33,000 in 1790 to nearly 200,000 by the time Moore’s poem was written in 1822. He even included a chimney in his poem for Santa to climb down as a way for city folk to better relate to a scene he’d rather have happened in his bucolic hills of a New York of yore – an area today we call Chelsea.

What also changed was the gifts exchanged. Traditional Christmas gifts consisted of hand made food and goods forged from natural countryside surroundings. But as Christmas moved to the city, handmade gifts were displaced by store bought presents.

The first known American Christmas advertisement came from one of the country’s busiest ports, Salem, Massachusetts in 1806. Then two more in 1808 in both Boston and New York in the New York Evening Post. By the 1820s they were everywhere. In 1834 a Boston magazine wrote,

“’All the children are expecting presents, and all aunts and cousins to say nothing of near relatives, are considering what they shall bestow upon the earnest expectants.… I observe that the shops are preparing themselves with all sorts of things to suit all sorts of tastes; and am amazed at the cunning skill with which the most worthless as well as most valuable articles are set forth to tempt and decoy the bewildered purchaser.’”

It went on to warn shoppers to “’put themselves on their guard, to be resolved to select from the tempting mass only what is useful and what may do good…’”

Sounds like Black Friday.

THE LUSTRE OF MID-DAY TO OBJECTS BELOW

While there was aggressive advertising as early as the 1800s, there was a social stigma around being too showy with luxury purchases. It was a sign of European aristocracy that the colonists, of all economic strata, were keen to avoid. But Christmas time had long been a cyclical excuse to overconsume. Shopkeepers and manufacturers latched on this association tempting even the most tempered to exult in excess through advertising, promotions, and sales.

It was the Puritans who invented Thanksgiving as way to celebrate the harvest separate from the religiosity of Christmas time. The specific day on the calendar bounced around until the late 1700s when regional governors dictated it be celebrated as close to Christmas as possible. It was even held on December 20th one year.

It didn’t take long for Thanksgiving to become commercialized either. New England farmers and merchants would strategize on how to best profit from the carnival-like drunken festivals that surrounded Thanksgiving just as it did Christmas.

Once Abraham Lincoln declared the last Thursday of November to be the official day of Thanksgiving in 1863, retailers could plan their profits around a firm date. Then, in 1934, Franklin Delano Roosevelt moved it back a week during the depression to extend the Christmas shopping season an extra week so retailers could reap more profits. It was a controversial ruling and FDR’s date came to be known as Franksgiving. Happy Franksgiving, everyone!

The 1900s was also the time when the marauding tradition of parading through the streets became a sponsored event by department stores. Eaton department store sponsored the first in Toronto in 1905 and then Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade came along in New York City in 1924. These parades began an unwritten rule among retailers to refrain from advertising Christmas sales until the parade had commenced. That made the Friday after Thanksgiving the first day shops were open for business and the start of holiday shopping.

The term ‘Black Friday’ didn’t enter the picture until 1961 in Philadelphia. ‘Black days’ were customarily days marking bad events. So much like the dread of the chaotic colonial traditions of parading wassailers, the Philadelphia police came to describe the traffic, congestion, and shopping hysteria the day after Thanksgiving as ‘Black Friday.’

But retailers didn’t much like the negative association. It took 20 years before a new association was cemented. And it was, again, Philadelphia that led the charge. A November 28th, 1981 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer was the first to describe Black Friday as the day when retailers, who suffered ‘in the red’ for most of the year, could move their ledger into the ‘black’ during the holiday shopping season.

Black Friday triggers an event, just as solstice did for the Romans, that offers an opportunity for those in power, capitalists in the form of retailers, to open their doors just as the wealthy land owners did, and offer great deals to those who can’t afford various luxuries, like figgy pudding, rum spiced pie, perry, or wassail.

Just as Roman slave owners used the Saturnalia to remind slaves of their place in society, or wealthy land barons to remind peasant laborers of theirs, capitalists use the holiday season as an chance to remind us all who’s in charge. And what Pintard, Moore, and their band of wealthy Knickerbockers did was wrap it all up in a fairy tale that portrays it all as benevolence by tying it to the Christian saint known for charity – Ole St. Nick.

They feared the masses becoming educated and empowered with the right to vote. They railed against democracy sensing it would only loosen their grip on power. And here we are on Black Friday of 2021, the start of the holiday shopping season, as powerful conservatives in Washington are drooling over ways to carve up a bill that represents the biggest investment in America’s most needy since FDR like it was a Thanksgiving turkey. Pass the wassail, please.

Reference:

The Battle for Christmas. A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday. Stephen Nissenbaum. 1997