Hello Interactors,

I ran into a friend last week who shared a bit of neighborly news. A border dispute is brewing in our neighborhood and you can bet maps are soon to be weaponized. It’s nothing new in border disputes around the world, but do maps really lead to a shared understanding of people and their interaction with place? It may be time cartography gets radical.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

COMMUNITIES DEMANDING IMPUNITIES

I step quietly as I near the end of the private lane. Ahead there’s a beige colored fence, barely six feet high, blocking the pathway. It’s attached adjacently to a fence bordering the owner’s yard. As I gently approach the fence I see a dingy string innocently dangling from a small hole in the upper right corner near the fence post. A slight tug on the string and I hear a metal latch release on the other side. It’s not a fence after all, but a secret gate.

I push it open and slither through sheepishly looking around to see if I’d been caught. I’m careful to lift the cold black metal latch to silence it as I gently close the gate behind me. I scurry past the driveway glancing at the house. My pace quickens down the remainder of the private lane before me. I self-consciously scurry by neighboring homes and scamper up a steep hill before triumphantly stepping onto the territory of public domain: a city street.

This secret passage along a private drive is known to longtime locals in the neighborhood like me. The gate sits on private property connecting two private lanes that connect two public parks at each end. Adventurous out-of-towners looking to walk or bike from one park to the other usually see the gate masquerading as a fence and turn around. But for as long as these roads have existed, locals have hastily snuck through the graciously placed gate.

But the fate of this gate is a question as of late. Do they have the right to block a pedestrian route that connects public parks even though it’s on private land? Or do they have the duty to honor the traditions of a community that has relied on this path for decades if not centuries? To answer these questions, governments, corporations, and individuals turn to legally binding property maps. Instead of arming themselves with their own maps in a race to the court, perhaps they should join arms around one map seeking mutual support.

The word map is a shortened version of the 14th century middle English word, mapemounde. That’s a compound word combining latin’s mappa, “napkin or cloth”, and mundi “of the world” and was used to describe a map of the world that was most likely drawn on an ancient cloth or papyrus.

This etymology resembles cartography from latin’s carta "leaf of paper or a writing tablet" and graphia "to scrape or scratch" (on clay tablets with a stylus)”.

Given modern cartography’s reliance on coordinates, the word cartography easily could have emerged from the word cartesian. That word is derived from the latin word cartesius which is the Latin spelling of descartes – the last name of the French mathematician, René Descartes. Descartes merged the fields of geometry and algebra to form coordinate geometry. It was a discovery that, as Joel L. Morrison writes in the History of Cartography, formed the

”foundation of analytic geometry and provided geometric interpretations for many other branches of mathematics, such as linear algebra, complex analysis, differential geometry, multivariate calculus, and group theory, and, of course, for cartography.”1

This two dimensional rectangular coordinate system made it easy for 17th century land barons and imperial governments to more easily and accurately calculate distance and area on a curved earth and communicate them on a flat piece of paper. The increased expediency, accuracy, durability, and portability of paper allowed Cartesian maps to accelerate territorial expansionism and colonization around the world.

But rectangular mapping of property, Cadastral Mapping, dates back to the Romans in the first century A.D. Cartography historian, O. A. W. Dilke writes,

“One of the main advantages of a detailed map of Rome was to improve the efficiency of the city's administration...”2

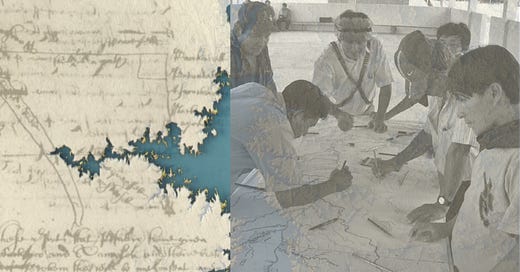

Even as Descartes was inventing analytical geometry in the 1600s, European colonizers in the Americas were using rectilinear maps in attempts to negotiate land rights with Indigenous people. For example, between 1666 and 1668 a land deed clerk filed a copy of a map detailing a coastal area in what is now as Massachusetts near Buzzards Bay. The original map was drawn by a Harvard educated Indigenous man named John Sassamon who was also a member of the Massachusett tribe.

Sassamon was respected by colonizers because he represented the ideal of an assimilated native but he was also held in high regard by local tribes…including the Wampanoag for which this map served as a legal document. He was an asset to both populations and served as an interpreter in a wide range of negotiations between tribes and colonizers.

This map was used by the Plymouth colonists to negotiate terms over Wampanoag land with their leader Metacom (or as he was also known as, King Phillip). It shows a rectangle featuring a river on the left side of the map labeled, “This is a river”, a line drawn at the top and the bottom labeled, “This line is a path”, and on the right side is a vertical line that encloses the rectangle. Surrounding the area are names of tribes and a body of text at the bottom describing the terms of the deal.

Herein lies a controversy, the intention of the map, and the fate of the mapped land. The text can be read one of two ways:

“Wee are now willing should be sold” or “Wee are not willing should be sold”.

The full statement in the records reads:

“This may informe the honor Court that I Phillip arne willing to sell the Land within this draught…I haue set downe all the principal! names of the land wee are not willing should be sold. ffrom Pacanaukett the 24th of the 12th month 1668

PHILLIP [his mark]”3

Nine years later, in January of 1675, Sassamon warned the governor of the Plymouth Colony, Josiah Winslow, that Metacom (King Phillip) was planning an attack. The Wampanaog, and other tribes, had become frustrated and threatened by encroaching colonists. Days later Sassamon’s body was found in a pond.

At first many thought he had drowned fishing, but further evidence revealed his neck had been violently broken. A witness came forth claiming to have seen three Wampanoag men attack Sassamon. The three men were tried before the first mixed jury of Indigenous people and European settlers. They ruled guilty and all three men were hung.

This created increased tensions and mistrust between Metacom and the Puritans leading to the King Phillips War in the summer of 1675. The battle lasted three years, most of which was without Metacom. In August of 1676 he was hunted down and shot by another Indigenous man who had converted, forcibly or voluntarily, to Puritan ways. Metacom’s wife and children were captured and sold as slaves in Bermuda. Metacom was cut into quarters and his limbs were hung from trees. His head was put on a post at the entrance to the Plymouth colony where it remained for two decades.4

LABORERS MAPPING WITH NEIGHBORS

Violence against and dispossession of Indigenous people by colonists and industrialists usually involves a map. That’s as true today as it has been at least since the Romans. But it hasn’t stunted attempts over the years to reduce or eliminate these injustices. For example, at the end of World War I, while U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and his Inquiry team were remapping Europe at the Paris Peace Conference, the League of Nations was born.

Out of this organization came the International Labor Organization (ILO) with representatives from Belgium, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, France, Italy, Japan, Poland, the United Kingdom and the United States. It was chaired by the head of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), Samuel Gompers. Founding members were made of representatives from government, employers, and workers. In the interest of creating a peaceful, safe, and just world, they intended to establish fair labor practices around the world, including fair pay for women – a provision Gompers brought to the table himself. Two lines of their founding preamble stand out amidst today’s international social disorder,

“Whereas universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice…

Whereas also the failure of any nation to adopt humane conditions of labour is an obstacle in the way of other nations which desire to improve the conditions in their own countries.”5

Social justice and historic income inequality are conditions that need improved among most countries today as they did in 1918. But when it came time to ratify the permanent ILO members, the U.S. Congress voted to deny Gompers a seat at the ILO table. U.S. politicians were suspect of the League of Nations and many feared these international labor rights may interfere with privatized labor in the United States. It wasn’t until 1934 that the U.S., with the urging of FDR, was allowed to take a seat at the ILO by the U.S. Congress.

Nonetheless, during the 1920s the ILO conducted several studies concerning labor conditions around the world. That including the subjugation of Indigenous Peoples as a result of widespread colonization. In 1930 ILO 29 was passed drawing much needed attention on forced labor of Indigenous and Afro-descendant people.

For the next two decades the ILO continued to conduct research and create programs throughout their conventions. In 1951 the ILO Committee of Experts on Indigenous Labour devised a 20 year blueprint that addressed land and labor rights of Indigenous populations. They brought together various UN organizations like the World Health Organization, the Food and Agriculture Organization, and UN Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. It culminated in the publishing of a 1953 report on the core social and economic conditions facing Indigenous Peoples in the Americas.6

Four years later this work made its way into the passing of ILO 170 as part of the Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention of 1957. The preamble includes language that admits there exists,

“in various independent countries indigenous and other tribal and semi-tribal populations which are not yet integrated into the national community and whose social, economic or cultural situation hinders them from benefiting fully from the rights and advantages enjoyed by other elements of the population…”

This was the world’s first attempt to codify Indigenous rights into international law through a binding convention. These conventions included government made maps that were used as legally binding documents. Up to this point in history almost all legally binding maps were produced by governments. But with the spread of neoliberalism around the globe in the 1950s, mapping efforts began to be outsourced from governments to private firms and corporations. This shift was amplified by U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s Point Four Program that offered technical assistance to developing countries, especially Latin America, and was largely funded by private institutions like the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations.

Neoliberal economists out of the University of Chicago, Chicago Boys, were also embedded in Latin American governments in hopes of spreading neoliberal policies that favored U.S. industries. Conservative politicians, emboldened by the Cold War, also feared these countries may turn to socialism or communism; especially given the majority of the founding members of the ILO and the League of Nations favored social programs as a means of protecting and providing social justice and stability. The U.S. stood alone in opposition to these principles and policies, but remained influential nonetheless given the U.S. military and monetary domination.

But the privatization of legal and technical documents by neoliberals, including maps, resulted in unintended consequences. If within the ILO trifecta of “government, employers, and workers” governments and employers could provide legally binding maps and documents, so could workers. This opened an opportunity for Indigenous communities, and their advocates, to provide their own maps that countered centuries-old border claims and land rights made by expansionist governments and industrialists, both of which are inextricably linked.

The language in ILO 170, while groundbreaking, was still drenched in paternalistic chauvinism and assumed assimilation of Indigenous Peoples as the binding element. One example is shown in the preamble above, “not yet integrated into the national community.” Over the course of the following 40 years Indigenous Peoples worked with the international community to revise the language. In 1989 the ILO passed ILO 169 which “takes the approach of respect for the cultures, ways of life, traditions and customary laws of Indigenous and tribal Peoples who are covered by it. It presumes that they will continue to exist as parts of national societies with their own identity, their own structures and their own traditions. The Convention presumes that these structures and ways of life have a value that needs to be protected.”

However, the word Indigenous Peoples was footnoted. In a compromise to include language of Indigenous self-determination, the ILO asked that the United Nations take up the matter on self-determination claiming it was beyond the scope of the ILO.

Indigenous people continue to advocate for their rights as “workers” through labor organizations in the ILO trio of “government, employers, and workers.” Only 23 of the 187 countries in the ILO have ratified ILO 169 and the United States and Canada are not among them. Most all are in Latin America and one of the most lethal legal weapon Indigenous people have continue to be counter-maps – maps that counter centuries of exploitive hegemonic colonialism.

FROM FALLABLE MAPS TO TANGIBLE RAPS

After decades at successful attempts at counter-mapping, it may have run its course. Governments and corporations have come to use maps to gain further legal control over Indigenous lands through abundant resources and political maneuvering. If the courtrooms of international law were a knife fight, governments and corporations show up with laser guided missiles. Labor unions in those 23 countries that ratified ILO 169 struggle for leverage, representation, and a voice – especially unions representing Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities. And if they’re suffering, imagine the masses of unrepresented workers in the remaining 164 countries who have not ratified ILO 169.

Meanwhile more and more natural resources are sought in increasingly sensitive environmental areas, like the Amazon forests, where the majority of biodiversity and CO2 sucking vegetation is protected by Indigenous communities and their way of life. And as global warming increases, their living conditions will likely lead to more dispossession and even extinction.

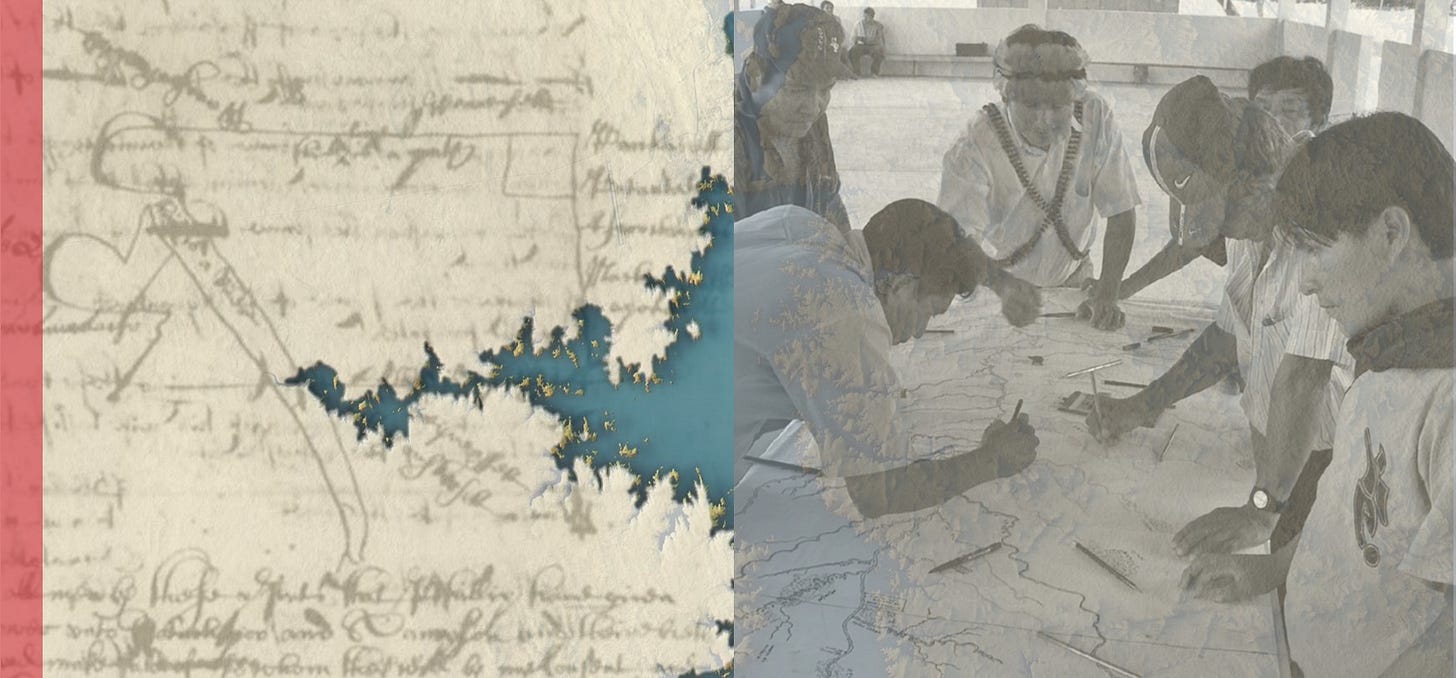

Mapping technologies since 1989 have also become progressively democratized. They’ve empowered even more people to take to cartography to get their voices heard, claim their land, and their way of life. There has also been a steady increase in members of these Indigenous populations earning degrees in science, social science, technology, and law. They’ve also found increasing numbers of likeminded scholars, intellectuals, activists, and practitioners from the around the world to help.

Bjørn Sletto, Joe Bryan, Alfredo Wagner, and Charles Hale are four such examples. They are editors of a recent book called Radical cartographies : participatory mapmaking from Latin America published by the University of Texas Press. It “sheds light on the innovative uses of participatory mapping emerging from Latin America’s marginalized communities”. It’s a “diverse collection” of maps and mapping techniques that “reconceptualize what maps mean”. They argue what is missing, even in counter-mapping, are “representations of identity and place”.

The lead editor, Bjørn Sletto, is a native of Norway, was educated in the United States, and has lived and researched in Indigenous communities and border cities in Latin America. He writes in the introduction that

“Beyond making claims on the state, Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities appropriate participatory mapping technologies to strengthen self-determination, local governance, and resource management within their own territories…”

What he’s found over decades of experience is that,

“This fundamental rethinking of the role of maps and the different ways they can be created, analyzed, and remade is driven in large part by inhabitants of the territories themselves, rather than by Western scholars or NGOs.”

These scholars have compiled a book that gives these Ingenious people voice and representation through their own methods of cartography. They’ve been allowed to describe geographies “in their own language and on their own terms.” By “describing and depicting the natural and built environments emerging from Indigenous, Black, and other traditional groups in Latin America” they are able to “demonstrate that these radical mapping practices are as varied as the communities in which they take place”.

María Laura Nahuel is one contributor in the book. She is a resident of the Mapuce Lof (Community) Newen Mapu, Neuquén, Argentina and received her undergraduate degree in geography from the Department of Humanities at the National University of Comahue, Argentina. She writes that,

“the current political, economic, cultural, and judicial context of our work has led us to think carefully about how the state’s historic monopoly over cartography has served to subjugate the ancestral and millenary wisdom of our people, the Mapuce. In particular, new multinational resource extraction projects, which are endorsed by the Argentine government, threaten our livelihood and subject us to a constant state of tension and uncertainty. This reality has led us to develop territorial defense strategies as well as plans for achieving kvme felen, or a state of good living. Mapuce participatory cultural mapping plays a key role in this process.”

Co-editor Joe Bryan is another contributor in the book. He is the associate professor in geography at the University of Colorado, Boulder where he focuses on Indigenous politics in the Americas, human rights, and critical cartography. He asks in the book’s concluding commentary:

“What is a territory? The question pops up repeatedly across the chapters in this volume. After all, what are mapping projects if not attempts to define territory? The problem, as several of the authors suggest, is that mapping affords a partial understanding of territory at best. At worst, mapping runs completely counter to Black and Indigenous concepts of territory with potentially devastating results. That outcome makes the question of what a territory is all the more pressing...”

He goes on to observe that,

“We are used to thinking of territory as a closed object, a thing that can be mapped, recognized, and demarcated. The dominance of this concept is reinforced by mapping, beginning with the use of GPS units and other cartographic technologies to locate material instances of use and occupancy... Legal developments reinforce this approach, pushing titling and demarcation as a remedy to the lack of protection…”

The owner of the property on which that gate I sometimes sneak through wants to build a new home. Their plans don’t leave room for a gate nor are they particularly interested in maintaining a right of way for the public. It’s caused a kerfuffle in the neighborhood. Home owners on this private lane want their privacy while their neighbors want to maintain access between parks.

It’s a battle of territory and maps are the weapon. Individual home owners show title maps that reveal there is no public easement on the private lane. The city acknowledges there is no easement in their maps either, but are acting in the interest of the majority and asking owners to grant easements so the path may remain. It may come down to the courts to decide and you can bet maps will be involved. But as Joe Bryan says, maps afford only a partial understanding of territory.

I’m not suggesting the problems of affluent suburban property owners are of equal consequence to the existence and rights of Indigenous and Black communities or the protection of vanishing natural resources. But what they do have in common is the insufficiency of traditional Cartesian maps to adequately represent interests of governments, corporations, and individuals in battles over borders and territories. Especially when their weaponized.

A primary trigger of the King Phillip War in 1675 was the encroachment of European colonizers. This led to misrepresentation, misunderstanding, and miscommunication of territory use and rights on a Cartesian map drawn by an Indigenous member of the Massachusett tribe supposedly seeking shared understanding between cultures. Here we are in 2022 where technology and enlightened cultural sensitivity abounds, and rigid Cartesian maps are still leading to dispossession and violence of under-represented and vulnerable communities.

But like the Europeans that colonized these lands over 500 years ago, we are turning to Indigenous people for guidance on how best to map and understand territories. We are again asking them to use maps as a way to best interact with people and place through what the editors of that book call radical cartography. Perhaps it’s time we put down our weapons of maps destruction and draw a map together. It just may draw us all closer together. How radical is that?

The History of Cartography, Volume 4: Cartography in the European Enlightenment. Joel L. Morrison. 2019.

The History of Cartography, Volume 6: Cartography in the Twentieth Century.

The History of Cartography, Volume 2. Book 3. Chapter 4. Maps, Mapmaking, and Map Use by Native North Americans. G. MALCOLM LEWIS

Blood and Betrayal: King Philip’s War. Historynet. Anthony Brandt. 2014.

History of the ILO. ilo.org. 2022.

Cultural Survival. After 30 Years, Only 23 Countries Have Ratified Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention ILO 169. Chris Swartz. 2019.

Share this post