Hello Interactors,

Do you ever walk through a neighborhood and wonder where all the people are? It happened to me last weekend. What’s worse, it was a 1960s planned development that reminded me of the suburb where I grew up. I don’t remember the streets being this quiet, but maybe these planned communities were meant to be this way. Or maybe we’ve changed. Or both.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

A DASH TOWARD THE PAST

There it sat in the driveway, a brawny black pickup truck with an NRA sticker in the rear window and TRUMP plastered on the bumper. The protruding chrome tailpipe was gaping wide. Black exhaust dust clung to its edges. Three late-model cars were parked askew in the front lawn. Two doors down and across the street I saw a pride flag hanging next to a Black Lives Matters sign that read, “WHITE SILENCE IS WHITE VIOLENCE.”

I passed more houses and heard a barking dog approaching angrily. It ran alongside a taco truck parked in a driveway with the name of a Mexican restaurant painted on the side. Two other cars were in the driveway and one in the lawn behind a chain-link fence that restrain the dog. I had walked nearly an hour in this suburban neighborhood and had yet to see a single human being.

I was at my son’s track meet last Saturday in a town near Tacoma called Federal Way. I had some time to kill so I decided to take a walk. I picked a green patch on Google Maps that appeared to go down to the water and headed off to explore. The sidewalk from the High School ended 50 feet from the parking lot and I never saw another. The streets were quiet in this 1960’s neighborhood scattered with single story ranch-style homes intermixed with two-story split-level boxes.

Melancholy reflected off of these beige, white, and brown painted homes. They all featured a yard, a driveway, assorted overgrown shrubs and a tree or two. These homes are identical to the homes I would run in and out of as a kid in small town suburban Iowa. They were all built as part of the post-war building boom during America’s economic heyday when ordinary, mostly White, middle class folks could buy into the American Dream.

This housing development was built to accommodate a booming population drawn to jobs at the Tacoma Port, nearby Boeing factories, lumber yards, and paper mills. As the 1964 King County Comprehensive Plan states,

“…certain areas in King County, such as Federal Way, will have a population boom partially due to the employment opportunities that exist or are contemplated in the Tacoma area.”1

Development was happening so fast that in 1958 the State of Washington purchased a 300-acre swath of land at nearby Dash Point for $185,000 to make it a state park. That’s $1.7 million in 2022 dollars and about what you’d pay for a single home near Dash Point today. Indigenous people lived on these shores before being displaced to a nearby reservation as part of the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek. The Puyallup people are still fighting for access to surrounding private land to fish; their lawful right as written in the treaty. Most, if not all, treaties fail to honor Indigenous notions of shared use of land and resources that fly in the face of more self-centered and guarded Western ideals and philosophies of individual property ownership and rights.

The state’s 1958 purchase of the Dash Point property was from a company aptly named the “Modern Home Builders.” That same year natural gas pipelines were laid and fire hydrants were getting installed every 600 feet. In 1959 a sewer plan was revised to keep up with the rapid development.2

In 1960 a 600-acre “Residential Park” began showing their 650 homes to buyers – many of whom were likely war veterans who were enjoying cheap government subsidized mortgages. Churches were being erected, bowling alleys were being laid, and ‘American Concrete’ had their grand opening featuring “Free Washed Sand for the Kiddies.”3

This Federal Way neighborhood I was walking in wasn’t the only one going through this transformation in the 1950s and 60s. It was happening across the country. I grew up in one and benefited from it. It was easy for me to imagine these homes as brand new. I could close my eyes and smell fresh white American concrete, I could see kids riding their bikes, new cars pulling into the driveways, and smoke rising from the backyard barbeques. Life was good.

By 1966, when most of this neighborhood I was walking through was built, the U.S. stock market had peaked. Nobody would have believed it then, but this marked the beginning of a long slow economic decline. The stagflation of the 1970s and the area’s shift toward software in the 1980s and 90s froze much of Federal Way in the past. Beginning in 1990 with the Washington Growth Management Act suburban sprawl was curbed, then much of Boeing left the area, mills closed, and Western Washington jobs shifted from blue collar to white.

Meanwhile, today the tech industry continues to push home values across the region upward while most incomes remain stagnant. The median price of a home in Federal Way is $580,000 and has grown 16% year over year for the last five years. The estimated yearly median income between 2013-2017 was around $62,000 and the per capita income was only $30,288. That’s well below the 2020 median household income in the United States of $67,521 which had dropped from $69,560 the year prior. Federal Way may be lagging economically, but it is extremely rich with diversity. The Federal Way School District reports over 111 different languages spoken in family homes. But not in the streets where I was walking. Not a peep.

This is a common sight in many suburban neighborhoods, and this one was no exception. Though, seeing one to five cars per household led me to believe these people must be home. I can imagine each of these homes filled with people glued to a screen. But should they ever leave, they’ll surely get in a car given the walkability score of 22 out of 100. Besides, there aren’t many places of interest within walking distance. Unless, of course, you’re a walking fanatic like me.

CURVESOUS CARTESIAN CUL-DE-SACS

This area, like so many others, was designed to be anthropocentric – it puts the individual self at the center. Just as cars do. America is made for cars and driving a car conjures a belief that the ‘self’ is most important. This is my car and my road so get out of my way. Automobile advertising repeatedly reinforces the image of being alone in comfort in a climate controlled moving cocoon made of metal and plastic. It’s hard to deny, a good car is comfortable.

And most of them comfortably reside at these single family homes which are also designed to put the ‘self’ and the ‘single’ family first. The handful of Christian churches I walked by also stress the power of the individual. The Bible’s Book of Genesis verse 1:26 states:

“God” said “Man” has “dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.”

Does that not sound kind of creepy?

Civil Engineers and Urban Planners were, and still are, the gods who hold dominion over city plans that often encourage cities to creepeth upon the earth. Federal Way itself crept out of sprawling Seattle and Tacoma. Planners made sure to plan for demand and single family homes on a large piece of land is what people demanded…and developers happily lent a hand. These demands have not receded. The 1964 King County Comprehensive Plan addressed ‘Residential Land Use’ with these words,

“Over the years and especially after World War II, the continued construction and upgrading of highway facilities has consistently improved accessibility to major employment centers. Since there has been ample suitable residential land available in relation to the demand, the effect of improved accessibility has resulted in residential development being located farther and farther out from major centers of employment. From the earliest times of the history of King county, a larger percentage of its residents have shown a preference to living in single family dwellings as opposed to multi-family structures. They could always afford this preference.”

They noted that in 1960 Seattle used 36 acres per 1000 persons, but by 1964 were planning to double that to 72 acres per 1,000 persons outside the ‘Urban Area’ of Seattle. They said,

“In the past, the grid iron pattern resulted in more acreage in streets than recent development.”

And since the 1950s and the expansion of freeways and highways there would be less need for the grid and compact development. They said,

“In the future, a large percentage of the streets and highway system acreages will consist of freeway type facilities rather than local streets.”

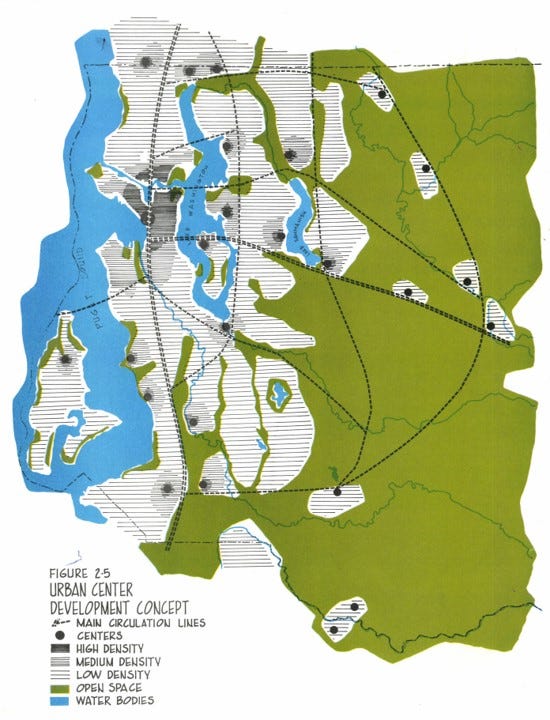

And to make sure developers, for whatever reason, didn’t attempt to build more dense housing on these sprawling acreages they included language that protected residents who may resist such attempts. They draw special attention to “URBAN CENTER DEVELOPMENT” (their emphasis), They wrote,

“residential densities should decrease at greater distances from an urban center…Some areas of the County should be kept at a lower density even though close to an urban center. These areas include locations where a pattern of large lot sizes is already established or is desired and where residents need the assurance that the character of their neighborhood will be stabilized.” (my emphasis)

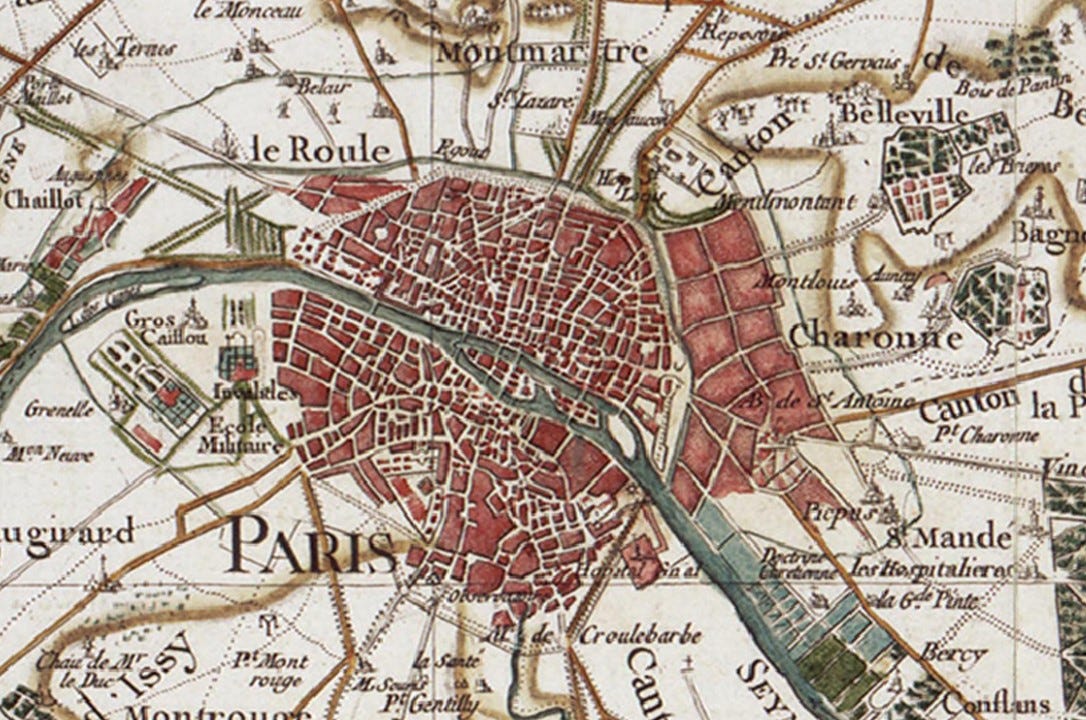

There is a discernable distaste for uniform Cartesian grids in the language of this plan. Part of the modernist post-war vision was to move away from compact urban development of the 19th century that favored neighborhood stores, modest property allocations, and use of public transit. Multi-family structures had connotations of poor, often ethnically diverse, residents which by today’s standards are read as thinly veiled racist and classist biases. The 1950s and 60s pushed for more rural and pastoral land use that attempted to blend a growing middle class into a natural landscape connected to a freeway.

They wrote,

“The grid form of layout, while easy to design on the drawing board, can result in inharmonious relationships with the site. It can, however, add clarity to an otherwise confusing street pattern, but should be used judiciously to avoid monotonous rows of houses.”

They instead called for more organic street and lot layout saying,

“Depending on topography or other natural features affecting street design…an infinite number of variations exist in the arrangement of lots and houses and can be used to take advantage of natural features of the landscape.”

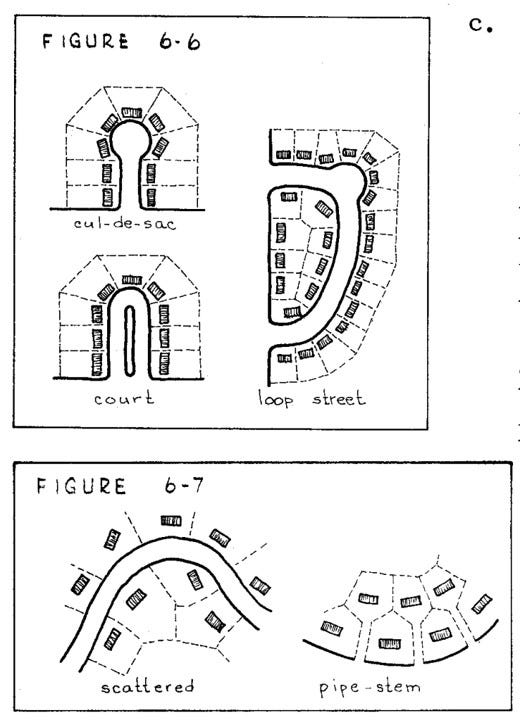

The cul-de-sac is called out in the plan as one example to follow.

“A third general form may be called a court, cul-de-sac, or cluster, and features a grouping of buildings which have service orientation at the street but privacy to the rear.”

I grew up on on a cul-de-sac and can vouge for the design goals these planners set out to achieve. But we now know that these dead ends can lead to overly circuitous routes should people choose to walk, bike, or bus to their destinations. They were planning for the automobile as the only viable and desirable choice of transport.

“residential neighborhoods should be designed with long blocks in order to avoid excessive cross streets which are costly to construct and maintain…Pedestrian crosswalks should be required only where necessary such as through blocks over 900 feet in length or where access to a school, park, or shopping area is essential.”

While they did recommend providing a sidewalk on at least one side of the street, it read more as a suggestion than a requirement. Under a section titled, “Street Design Factors” they said this about sidewalks,

“Even though sidewalks may be used less for walking in residential than in business areas, their hard surfaces provide children’s play areas close to home.”

THE APPRAISAL OF THE SOCIO-SPATIAL

The words “close to home” say a lot about these city plans and the desires and demands of home owners and builders. These places were designed and engineered by professionals from ‘above’ using maps and diagrams. They remained detached from the people and places they were planning for. And the very ‘townscapes’ these people were designing were intended to detach the occupants of these spaces from the larger, messy, and complex society that surrounded them.

They made plans for homes with ‘privacy in the rear’ where children play ‘close to home’. Architects and builders designed structures that insured privacy – in the words of ‘High Modernist’ Le Corbusier – they were “machines for living.” These properties included ‘service orientation at the street’ that included a driveway leading to a garage where the other ‘machine for moving’ could be stored.

This methodically mapped, measured, and mechanized ‘mecca’ is the making of well meaning men dating back to Mercator. The 17th century father of Cartography used techniques of triangulation to turn the earth into a scientific measuring instrument. The centuries old Mercator projection, which distorts northern land masses to give priority to the Dutch sailing distances between them, is still the most popular and familiar projection used today.

Then came Newton who saw the entire universe as a kind of machine – “a container for objects and facts.”4 He married his Newtonian physics with Euclidean geometry. The philosopher Immanuel Kant, who also taught physical geography, argued “space and time were inner conditions of the human…ordered by logical categories.”5

Starting in 1747, and over the course of 50 years, the Cassini family drew a highly precise map of France using geodesic triangulation – the first of its kind. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) expanded on these techniques to measure and delineate land across the United States. But theses topographical maps were also used for the erasure of certain natural elements and to eliminate certain people. After all, their primary purpose was, and still is, to wage war or defend against it. These maps also remain the basis for mapping, planning, and ordering urban areas in the United States to this day.

This Western anthropocentric, mechanistic, objectification of spaces, and the use of maps and drawings to represent them, is alluring and seemingly addictive. It’s also part of the reality of everyday urban life. Ali Madanipour, a Professor of Urban Design at Newcastle University, separates urban spaces into two dimensions: physical and social.

The ‘physical’ is what garners the most attention, probably because it’s most visible and easy to understand. The arranging and grouping of buildings is at the scale of an urban planner and politician, the form and function of buildings are the domain of architects and developers, and the patterns and construction of spaces in between these structures, like streets, alleys, highways, freeways, and parking lots, is the domain of the civil engineer.

These objects are arranged in space creating places where people interact with each other and the natural and built environment – the interaction of people and place. But these interrelationships extend to the people who build them and those who control how, when, and where they’re built. This complex, multi-dimensional, interconnected social dimension over space and time is hard to see, harder to visualize, and thus hardest for us all to understand.

Madanipour summarizes,

“A study of urban form therefore refers to the way physical entities, singly or in a group, are produced and used, their spatial arrangements, and the interrelationships, and also how monetary and symbolic values are attributed to them.”6

The way men mapped and arranged the physical entities in that Federal Way neighborhood were produced for the monetary gain of developers, the city, county, and state. The symbolic values were codified in that 1964 King County Comprehensive Plan that encouraged interrelationships between individuals to be in the home, close to home, or in a car – all while guaranteeing the ‘character of their neighborhood’ would be stabilized.

It was all planned on a map that men loomed over like a god or a general staging a battle over territory. But they were also giving people what they wanted. Weyerhaeuser wanted trees for paper and profit, developers wanted stolen land in exchange for money, and people wanted what many believe is entitled to them: individual ownership of their land. After all, it’s written in the preamble of the U.S. Constitution – to “secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity".

The GPS I used to navigate these quiet curvilinear roads, carved into the earth then cauterized with concrete, is rooted in the same Western history of cartography, science, and philosophy that assisted in building its physical urban form. But the space I was visiting was not designed to be used as I was using it. That is why, to some degree, I didn’t see a single person. This environment was not built to foster interactions between people and place, but for cars to move individuals through space.

This place was designed for these people to be ‘close to home’ and in the home. These residents were probably socializing and forming interrelationships, but in a virtual environment. There were being entertained on a screen in their hand, on a desk, or on a wall. The culmination of combined technologies as old as their homes.

And when they did finally decide to leave their home, they likely tapped their destination on their phone. They climbed into their ‘machine for moving’, and were instructed to drive to clusters of physical structures of their choosing. They then glided on surfaces of ‘in-between’ spaces across America’s concrete places. The American dream financed by a loan. Blessings of liberty, that has left them alone.

The Comprehensive Plan for King County, Washington. King County Planning Department. 1964.

Historical Society of Federal Way. Revised November 14, 2015.

Ibid.

Mapping as tacit representation of the colonial gaze. Tamara Bellone, Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro, Francesco Fiermonte, Emiliana Armano and Linda Quiquivix. From Mapping Crisis. Edited by Doug Sprecht. University of London Press. 2020.

Ibid.

Design of Urban Space: An Inquiry into a Socio-spatial Process. Ali Madanipour. Wiley. 1996.