Hello Interactors,

I’ve started to making my own milk again. It’s not really milk. It’s creamy colored water made from pulverized remains of nuts or grains that I sweeten with a little maple syrup. Invariably I get lazy and real dairy creeps back in. But every time I look at that carton, I know what’s inside didn’t come from that cute cow or that stylized farm on the label. And however it got here, I know it came at a cost greater than what I paid.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

MILK MAN

Rick has a phone to his ear with one hand while he clicks his mouse in the other. He’s searching websites for a hay baler part while calling neighboring farmers to borrow theirs until his part arrives. He clicks a browser tab that is already open to the weather forecast. Rain is coming. Tension mounts as friends and relatives kick into gear. The hay has to be cut before that rain comes.

Have you ever had milk straight from the cow? It truly tastes like milk you’ve never had. It was so good, I was warned to not drink too much or too fast. Gluttonous dairy consumption can lead to an upset tummy. But I was assured that if I ever wanted more, there was always a fresh container waiting in the refrigerator.

Chances are if you grew up with milk, your refrigerator has milk in it. It’s probably not straight from the cow, and it may just look like milk (oat milk is all the rage – especially once Oprah and Jay-Z got in on the action), but the West likes their milk and milk products. But consumer demand is worldwide. The more Taco Bells and Pizza Hut’s pop up on streets around the globe demanding cheese, the more milk supply is needed. Starbucks sells more milk than they do coffee. People like their milk and coffee.

I was in Mexico City once eating breakfast at a local eatery with a friend. The waitress sauntered around with a carafe of coffee in one hand and a pitcher of milk in the other. She’d walk up, make eye contact, and start pouring coffee until you said stop. She’d fill the rest with milk. I miss Mexican coffee.

It was hard for me to imagine a dairy farm in a mostly arid Mexico. Growing up in Iowa, I have images of vast grassy fields dotted with milk cows; a winding grove of water thirsty trees clinging to a creek or river bordering the farm. A&E Dairy was the only brand of milk I ever knew. They’ve been bringing milk to Iowans since 1930. We had an actual milkman as a small child. A gray sheet metal box with a blue A&E logo on the front sat nestled in the corner of our doorstep. He’d raise the hinged lid and gently place a glass container of milk inside.

By fourth grade, in 1976, that all had changed. We took a field trip to the A&E bottling plant in Des Moines, Iowa. I remember watching an industrial sized see-through bin full of white plastic pellets the size of ball bearings funneling into a heated form. After a couple seconds, a plastic one-gallon milk container emerged. The glass jar delivered by the milk man had been replaced by crates of one-gallon milk jugs. They’d load them into a semi-truck and off they went; onto a freeway that was as old as me.

A&E, like all American dairy producers, were just beginning to scale up their farms. President Richard Nixon’s Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz sent this message to American farmers, “get big or get out.” It was the beginning of the end for small and medium sized farms across the country as milk production steadily climbed from around 54 million tons in 1976 to nearly 100 million tons in 2018. It doesn’t show signs of stopping.

MILK: THE MAN

Rick, his wife Terri, and a team of extended family members were able to get the hay in the barn before the rain started to fall. But there was no time to rest. A semi-truck had backed its long shiny silver milk tanker up to the barn and was waiting patiently, though a little stressed, for some help. It was time to mix their milk with that of other producers in the Delaware River Valley just north of the Catskill Mountains in upstate New York. Both milk and water flow from this watershed south to an increasingly thirsty New York metropolitan area where urbanites peek up from their steaming molten chocolate cake at trendy restaurants to ask their waiter, “Got Milk?”

With milk production continuing to ramp up over my lifetime, these New Yorkers must not be the only ones craving milk. The entire country must be hankering for more. Not true. Despite American momma cows producing more and more milk every day, the average American milk consumption per capita in 2018 is equal what it was when I was born in 1965 – 256 kilograms per person per year. That’s around 65 gallons a year or just over five gallons per month. That includes cheese, but not butter.

If a growing American population doesn’t account for the growth of dairy production in America, that tells you American dairy farmers interested in endless growth and profits are relying on exports. But Milk is very expensive to ship given its weight. One gallon weighs 8.6 pounds. Because it’s 87 percent water, 9 percent skim solids, and 4 percent milk fat it needs to be broken down into dry ingredients. Dry milk and dry whey make it easier and cheaper to ship. Once it reaches its destination, it’s reconstituted into milk or cheese by adding water.

This has led to an explosion in commercial exports. The United States has become the world leader in nonfat dry-milk and dry whey exports. Their biggest markets are Mexico, China, Philippines, and Indonesia. To meet consumer demand and a growing food processing industry in China, a 2020 Department of Agriculture report expects exports to continue to grow.1

To meet this demand, the dairy industry continues to expand. And like Nixon’s Earl Butz “get big or get out” advice, Trump’s Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue said in 2019, “In America, the big get bigger and the small go out.” He said that in a speech at the World Dairy Expo in Wisconsin – a state known for cheese – where they lost 800 dairy farms that same year to consolidation.

Licensed dairy farms across the country numbered just over 70,000 in 2013 and is now a little over 31,000. A 55% decline in seven years. Meanwhile, the amount of milk they can get from a single cow has increased. Cow milk production has increased 11.5% since 2011 and the USDA is expecting increases to continue.

To get your head around how production increases while the number of dairy farms decreases, consider one of a half a dozen companies providing most of the milk to the world – Riverview. Based in Minnesota, their website seems corporate but kind. Maybe even a little innocent. It says,

“[They] utilize both rotary and parallel parlors. Each site is a little different from the others, but the activity is the same: milking cows. Each cow produces about eight gallons of milk per day which is sent to processing plants to make cheese.”

But they don’t talk about the farmer they approached proposing a 24,000-cow dairy near his farm in Minnesota. They were hoping to buy his corn to feed all these cattle. He couldn’t imagine a 24,000-cow operation and turned them down. In addition to worrying about the odor, damage to roads, and pollution, he was most concerned about the amount of water that would take.

One researcher estimates Riverview uses nearly one quarter of all the water used for hog and dairy farms in Minnesota. And they’re not through. State records show permits for two farms of over 10,000 cows. Minnesota isn’t the only state they’re interested in. They’ve extended into one of the most unlikely places to raise and milk cows (given my bucolic ideal of farm country) – the deserts of Arizona.

COCHISE CHEESE PLEASE

Rick and Terri started their farm from scratch. They raise three kids, endured and recovered from a house fire, and have managed to raise some amazing kids, award winning cows, and by my standards, some very tasty milk. But it’s getting harder and harder to make ends meet. Their youngest son is interested in continuing the farm, but prospects of survival are grim.

New York was the fourth biggest producer of milk in 2020 behind California, Wisconsin, and Idaho, but they were also fourth behind Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania in the number of dairy farms lost. New York state lost 240 small dairy farms last year. The pandemic didn’t help. And mega-farms have seized the opportunity to prey on financially vulnerable farmers – like Terri and Rick. But also farmers in Arizona where wells are running dry.

Riverview was most likely attracted to Arizona because of its lax water laws. If you’re a farmer in rural Arizona, there is no limit to the water you can use. But scoot your boots too close to roost near Phoenix or Tucson, and you’ll be wrestled, metered, and hog tied. So they picked a location made popular by California pistachio farmers who got there before they did – Sunizona, Arizona.

This town sits in the Willcox basin in Cochise County. It’s a dried lake bed, Lake Cochise, named after an ancient Indian culture that existed 9,000 – 2,000 years ago. In keeping with America’s enigmatic ways, it’s both a National Natural Landmark and a designated bombing range for the U.S. military. But it’s also home to acres of crop circles in a desert that is prone to dust cyclones. Sounds like a perfect place for a dairy farm.

Below this dusty playa is a vast underground water source. Sometimes. Its replenishment cycle has turned sporadic since large-scale agriculture came here in the 1940s. Before big-ag hit it had enough water to satisfy demand for residents of nearby Tucson for 970 years. And in more recent decades, the effects of climate change have resulted in the nearby mountains getting pounded with rain some years and other years nothing. Farmers are forced to dig deeper and deeper wells to capture a steady supply of water. In 2015 area farmers used four times more water than was being recharged. It’s created a race to the bottom. But digging wells isn’t cheap and the more money you have the deeper you can dig.

Imagine a friend offers to buy a drink to share. They sit down with a tall glass of your favorite icy concoction and then slide you a straw across the table as they dip theirs into the depths of the drink. You plunge yours in and take a long cool draw. Halfway through the drink you realize you’re only siphoning ice melt from the pile of cubes that have become exposed. Meanwhile your friend is happily slurping away from a straw longer than the glass. That’s when you realize your friend gave you a straw shorter than theirs. Some friend.

The farmers in the Willcox basin have built short-straw wells over the years to grow everything from nuts, to cotton, to alfalfa. But many can’t afford to dig deeper. So Riverview swoops in and buys them out. Many are happy to take the money and run, some are hoping Riverview’s money will spill over into the community, and others feel isolated, stressed, and bewildered.

Riverview is taking over the place. A money-rich mega-dairy from Minnesota who showed up with a straw twice as long as their neighbors. More short-straw farmers see wells run dry as desert dust turns green with grain to feed the thousands of Riverview cattle.

To get as much milk out of their cows as possible, operations like Riverview load 90 cows into a carousal that slowly spins in constant motion. Cows enter, get milked as it turns, and then get dropped off. An area that used to get treated to a deep dark night sky lit only by the milky way is now blinded by the light pollution of a 24-7 dairy operation. A water sucking corporate machine who will surely deplete this ancient basin of its water and then move on to the next aquifer. If there are any left.

WAVES OF WATER

You can see why my wife’s cousin, Terri, and her husband, Rick, can’t compete. They’re playing a different game. Having spent some time with them on the farm, I can tell you they have a love and respect for their cows and their land. And they’re proud of the thought somebody down the road, even in another state, is drinking milk they produced. In the presence of factory farming, in an era of ‘go big or go home’, Terri and Rick’s method of dairy farming is receding. That quaint, romantic, idealized grassy farm with a single cow that dairy’s print on their containers is vanishing faster than our water supply. And it will likely not return.

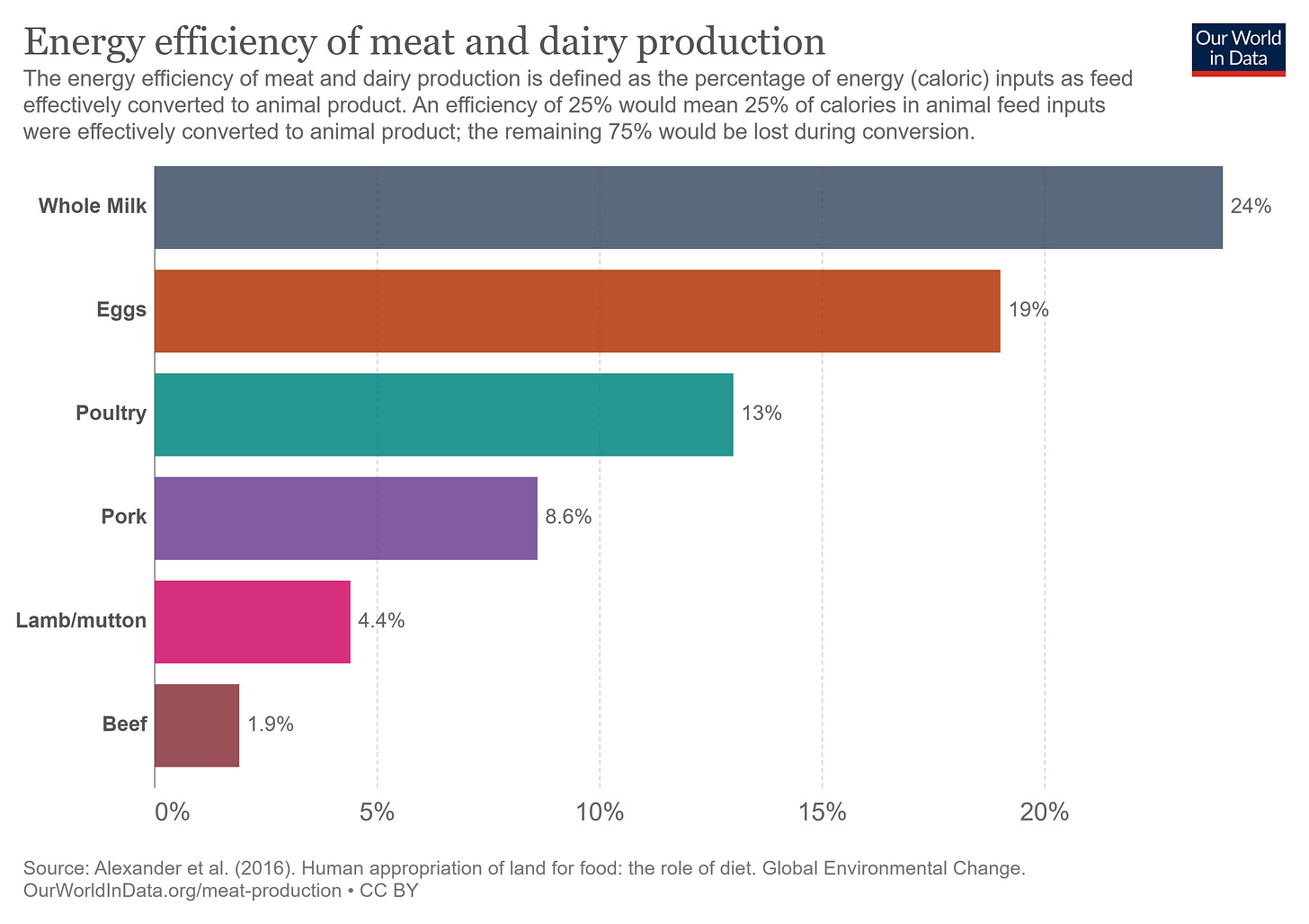

I remember a slogan from an ad campaign paid for by the American Dairy Association that read, “Milk does the body good.” It indeed does. It’s tied with eggs as one of the highest quality, efficient, and micro-nutrient rich foods you can consume. There’s evidence that the earliest domestication of cattle was by nomadic hunter-gatherers who discovered how handy it was to have a food source walk alongside you. Talk about efficient.

Energy we get from cow biproducts is minimal compared to what it takes to generate it.

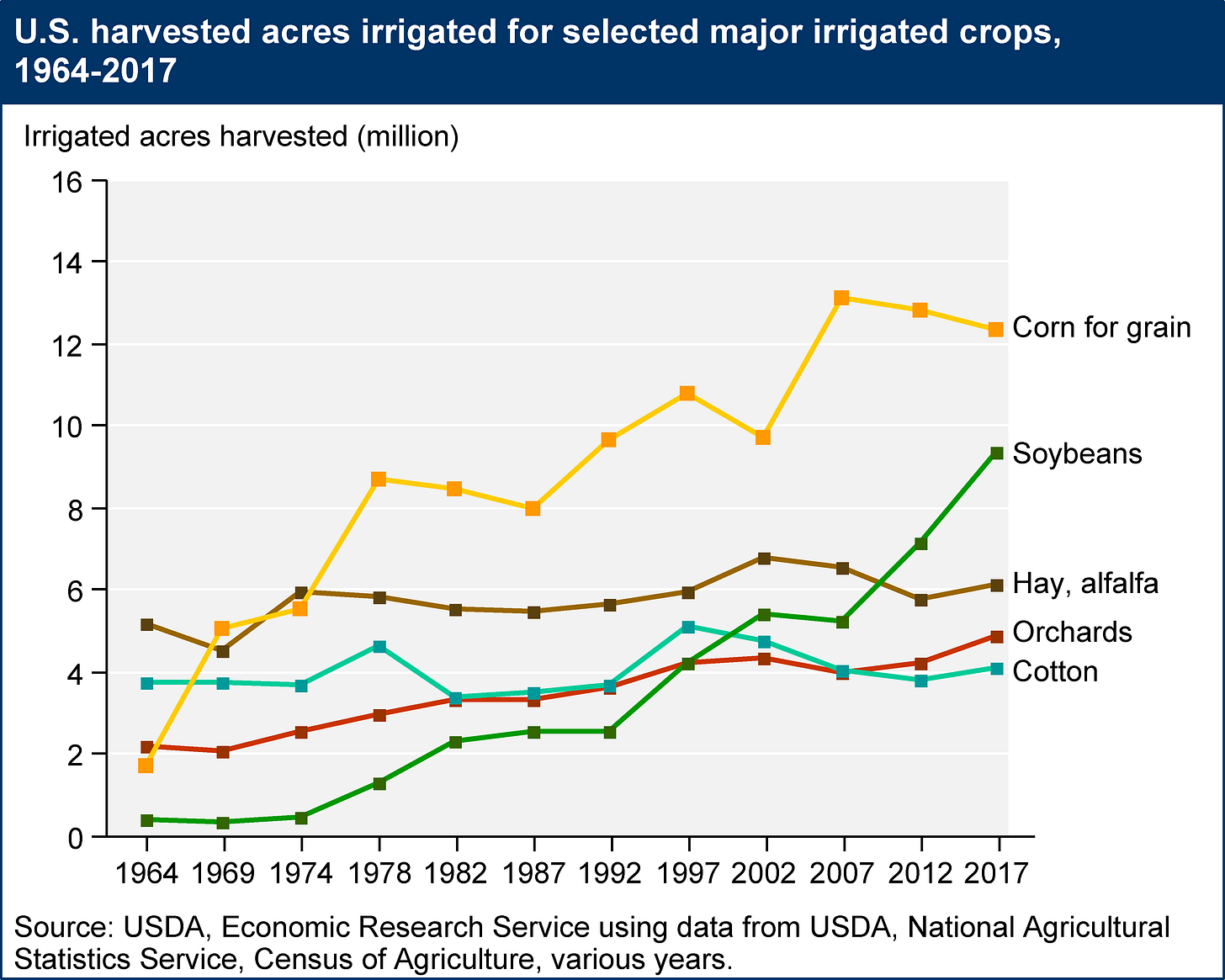

Feeding livestock requires tons of grain which requires tons of water. In the United States, roughly half of the water for agriculture comes from irrigation and the rest from local ground sources like the aquifer in the Willcox basin. But not all feed can be grown locally, so it’s grown elsewhere and trucked or shipped in. When I was born in 1965, 2.5 million acres of U.S. land was irrigated for corn and soybeans. In 2017 that had grown to 12 million.

California, the country’s biggest milk producer, draws far more water than any other state. But most of that water is drying up. As the West dries up, irrigation moves east.

Nebraska leads the country in the amount of land used for irrigation. California is number two.

But Nebraska is drawing from the Ogallala reservoir. This High Plains aquifer is one of the largest in the world. But it too is getting depleted. Conservation efforts have helped. Programs have been underway for years and together with new genetically modified corn that requires less water, depletion rates have lessened.

Increased in demand is coming from many sources: housing developments, corn and soybean crops, natural gas fracking, and hydraulic drills for oil pipelines to name a few. This, coupled with variation in replenishment rates from climate change, means natural habitat is at risk. A 2017 study used satellite imagery to examine the effects on wildfowl. Measuring multiple years of water inundation during replenishment cycles, they came to this conclusion:

“These results indicated that realized inundation was well below the capacity of the landscape as indicated by maps of potential playas. Thus, even when holding water, the observations here indicated the area of available open-water habitats, for waterfowl, for example, was below the potential capacity described by wetland maps.”2

MILKING THE ALTERNATIVES

Back in 2001, Rick and Terri drove their kids across the country in an RV. They passed by 3000 miles of farm country; over the Ogallala and across the arid West to our home in Kirkland, Washington. I was drinking soy milk at the time and had them all try their first swig of the so-called milk. Let’s just say not a single glass was emptied and the kids all looked at me sideways for awhile.

Plant-based milks are growing in popularity, but it’s mostly an elite urban phenomenon right now. And you can bet most of those oat milk drinkers still like their cheese. Most of the milk from Riverview’s tens of thousands of cows goes toward cheese production.

The truth is, we don’t have enough land and water to meet a growing worldwide demand for dairy products. Especially amidst exponential population growth. We’re facing a choice between sliced cheese on a dish or trees and the fish; ice cream in a bowl or a stream that meets the shoal. The Colorado River once rushed into the shoals of the salty Pacific Ocean, but now it runs dry inland in Mexico.

I can’t say I’m doing very well myself. I’ve reduced my dairy consumption and sometimes make my own Oregon sourced hazelnut ‘milk’, but I’m not fortifying it with the nutrients I get from dairy. And I’ve tried plant-based cheese. It’s not there yet.

Perhaps I shouldn’t beat myself up. Maybe U.S. farmers should stop chasing profits found in lucrative foreign markets and conserve the natural resources this country depends on. Maybe grow more food for people and less food for livestock. More milk and cheese for me please, let them find their own dairy over seas. I now that sounds dogmatic, but maybe it’s just pragmatic. Besides, rainfall is getting sporadic and population growth is dramatic. Meanwhile, the amount of freshwater in the world remains static.

Or maybe I stop hanging on to my Western dairy diet and seek appetizing alternatives. I may be better for it. Remember Rick and Terri’s advice? Gluttonous consumption of dairy can lead to an upset tummy. Greedy consumption of natural resources can lead to an upset global ecosystem. It’s time for a change. Terri and Rick are having to adjust to a new reality that challenges their past, maybe it’s time we all do. Especially companies like Riverview.

China: Dairy and Products Annual. USDA Office of Agricultural Affairs, Beijing. October 20, 2020.

Landsat Classification of Surface-Water Presence During Multiple Years to Assess Response of Playa Wetlands to Climatic Variability Across the Great Plains Landscape Conservation Cooperative Region. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey. 2017.