Hello Interactors,

This episode kicks off the summer season on the environment and our interactions with it and through it. I’m starting with food. Food is a big topic that impacts us all, albeit in uneven ways. It got me wondering about the global food system and how it’s controlled. Who are the winners and who are the losers? And why is there competition for nourishment in first place?

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

АТАКА БОЛЬШОГО МАКА (ATAKA BOL'SHOGO MAKA)

Верните Биг Мак! Срочно верните Биг Мак. Мы требуем этого прямо сейчас. Прямо сейчас. Прямо здесь. Биг Мак!

(Vernite Big Mak! Srochno vernite Big Mak. Moy trebuyem etogo pryamo seychas. Pryamo seychas. Pryamo zdes'. Big Mak!)

“Bring back the Big Mac! Bring back the Big Mac. We demand it right now. Right now. Right here. Big Mac!” Holding a handwritten sign that read “Bring back the Big Mac” a protestor in Moscow took advantage of a press conference a couple weeks ago at the reopening of McDonalds under a new name. Albeit a bit tongue in cheek, he was demanding the return of one popular product not on the menu. The Big Mac name and special sauce are both copyright protected. But the new owner of the new McDonald’s, Alexander Govor – who was a Siberian McDonald’s franchise owner before buying the entire Russian chain – promised he’d find a suitable replacement for the Big Mac. As for a new name, I vote for Большая говядина (Bol'shaya Govyadina), Big Beef. Or given the new owners last name how about just Bol’shaya Gov – Big Gov.

Govor claims he paid below market price for the world’s most recognized fast-food chain and he’s already slashed prices. McDonald’s priced the double cheeseburger at 160 rubles ($2.95) but it’s now 129 rubles ($2.38). The fish burger was 190 rubles ($3.50) and is now 169 rubles ($3.11). The composition of the burgers stays the same as does the equipment, but they did add pancakes, omelets, and scrambled eggs to the morning menu. However, the golden arches are gone, and the name has changed to Vkusno & tochka's (Delicious and that’s it or Delicious, full stop).

After 32 years, that’s it for McDonald’s in Russia but it’s promised to remain delicious. Back in 1990 the American based company had to import all the ingredients to fulfill the promise of a true McDonald’s. It made for an expensive introduction of the American icon. French fries were a problem. The Russian potatoes were too small, so McDonalds had to import seeds to grow larger russet potatoes locally. Apples for the McDonald’s ‘apple pie’ had to come from Bulgaria. After three decades McDonald’s managed to source just about everything locally and ultimately employed 62,000 Russians throughout their operations. But those McDonald’s branded red, yellow, and blue uniforms have been replaced with just red ones. Judging from the lines and enthusiasm at the grand opening, I suspect the new MickeyD’s will continue to be popular…and delicious, full stop.

McDonald’s was popular in Russia from the day it opened in 1990. The Berlin wall had come down, perestroika was nearing its peak, glasnost embraced a blend of socialism and traditional liberal economics that allowed more U.S. companies to enter the former Soviet Union. It was the age of exceedingly fast globalization. A year after McDonald’s showed up Microsoft offered a Russian version of DOS. Just as I was starting at Microsoft in 1992, localized versions of software were flying on floppy disks around the world. By 1996 localized versions of Windows and Office 95 were on a computer on every desk a new McDonald’s was being built every three days. 1996 was the first year McDonald’s made more revenue from outside the United States than within.

And McDonald’s wasn’t just pushing their McMunchies on unsuspecting countries. Many were clamoring for their own MickyD’s. James Cantalupo, president of McDonald's International at time, said,

“'I feel these countries want McDonald's as a symbol of something -- an economic maturity and that they are open to foreign investments. I don't think there is a country out there we haven't gotten inquiries from. I have a parade of ambassadors and trade representatives in here regularly to tell us about their country and why McDonald's would be good for the country.'”

There were some who believed the proliferation of McDonald’s symbolized the spread of freedom and democracy. Thomas Friedman of the New York Times offered in 1996 a “Golden Arches Theory of Conflict Prevention -- which stipulates that when a country reaches a certain level of economic development, when it has a middle class big enough to support a McDonald's, it becomes a McDonald's country, and people in McDonald's countries don't like to fight wars; they like to wait in line for burgers.” There goes that theory. Though, Russians are still waiting in line for a burger…just not from McDonald’s.

I’m reminded of the “freedom fries” scandal from 2003. That’s when the Republican senator from Ohio, Bob Ney, changed the name of ‘French Fries’ to ‘Freedom Fries’ in three Congressional cafeterias. It was in response to French opposition to the American invasion of Iraq. The name was changed back in 2006 after Ney was forced to retire. He was implicated in a scandal involving a group of lobbyists that swindled $85,000,000 from Native American tribes. Ney was bribed by one of the guilty lobbyists. On the satirical Saturday Night Live news show Weekend Update, Tina Fey quipped, “‘In a related story, in France, American cheese is now referred to as 'idiot cheese.'"

SEEDS OF GREED

Of course, McDonald’s wasn’t the only multinational food company spreading fast food around the world. I, for one, was grateful to come across a Burger King on the Champs-Élysées in Paris back in 1984. It was my first trip to Europe and my 18-year-old palette wasn’t quite tuned to fine French cuisine. Truth be told, my 56-year-old palette isn’t either. I find French food to be highly overrated. I remember my 18-year-old self thinking that “Le Whopper” and Pepsi with ice, amidst pumping French disco, was both surreal and comforting.

Pizza Hut, Domino’s, and Taco Bell are found in all corners of the world today. Except Mexico. Despite many gallant attempts, Taco Bell can’t seem to crack the Mexican market. I suspect Mexicans find their interpretation of the taco insulting…and gross. But it’s not just fast food. Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, General Mills, Kellog’s, Kraft, and Mars are all American companies that make a plethora of processed and packaged products marketed as food. There are other multinational companies outside of the U.S. doing the same. Mexico’s Grupo Bimbo is where Thomas English muffins, Orowheat, and Sara Lee treats come from. They also own Colonial bread: a white bread that originated in colonized America by a Scandinavian immigrant and is now run out of colonized Mexico by the grandson of a Spanish immigrant who could pass as just another white billionaire CEO.

And who hasn’t heard of Switzerland’s Nestlé products? They are so big there’s a wiki page just to list their products. Chips Ahoy cookie anyone? What about the Anglo-Dutch company Unilever? They bring us Ben and Jerry’s ice cream, Dove Bars, and Hellman’s mayonnaise. Have you ever had Nutella? That comes from the Italian company Ferrero. That single company consumes one quarter of the world’s supply of hazelnuts. Increasingly those nuts are coming from my neighboring state, Oregon. I love Oregon hazelnuts, so save some for me Ferrero.

This select group of companies produce, market, and sell most of the food around the world that is baked, canned, chilled, frozen, dried, and processed. Adding to the fat and sugar found in fast-food chains, they make dairy products, ice cream, meal replacements, bars, snacks, noodles, pasta, sauces, oils, fats, TV dinners, dressings, condiments, spreads, and an array of beverages. This gives them massive market leverage over the source ingredients produced by farmers around the world.

The very seeds needed to grow these crops are also controlled by a select group of multinational companies. The food policy advocacy group Food and Power reported:

“In 2020, the top four corporations, Bayer (formerly Monsanto), Corteva (formerly DuPont), Syngenta (part of ChemChina), and Limagrain together controlled 50% of the global seed market, with Bayer and Corteva alone claiming roughly 40%. And when it comes to genetic traits, this control is even more pronounced: Bayer controls 98% of trait markers for herbicide-resistant soybeans, and 79% of trait markers for herbicide-resistant corn.”

Carlos J. Maya-Ambía, a professor of Political Economy and Agriculture at the University of Guadalajara in Mexico, uses an hourglass as a metaphor to explain the control these companies have over the food making process. Imagine the top of the hourglass are the world’s farmers producing edible plants and animals and the bottom are the world’s human inhabitants – consumers. Both are wide and round. The middle of the hourglass is relatively narrow. These are the few multinational companies mentioned above who control most of the flow from the top of the hourglass (the farms) to the bottom (our tables).

Because these seeds are engineered for largescale monoculture farm productions that these corporations require. They tend to rely on agrochemicals to achieve desired yields. It’s a short-term positive yield strategy optimized for quarterly earnings reports, but with severe long-term negative consequences. And guess who controls an estimated 75 percent of the global pesticide market? Those same top tier seed companies.

These chemicals are largely petrochemicals, so the fossil fuel industry also profits from global food production and consumption. These processes, genetically modified seeds, and chemicals no doubt have helped bring countless people out of poverty and starvation. Especially where increasingly harsh conditions make it hard to grow crops. But at what cost? These industrial scale schemes not only leach nutrients from the soil and pollute water supplies, but exposure to these chemicals can also cause neurological disorders, birth defects, infertility, stillbirths, miscarriages, and multiple forms of cancer.

Worse yet are the inequities. Many of these chemicals and genetically modified foods are banned in developed countries. Before Monsanto was purchased by Bayer, massive protests across Europe led to the company pulling out of parts of the EU. Those countries with the most organized farmer and consumer protests had the biggest effect. It’s testimony to the power of democracy and organized protest. But Monsanto, and companies like them, just move on to more willing governments or vulnerable people and places. They seek lands far away from the peering eyes of consumers with a conscience. Many of whom who sit there munching snacks, and tapping on their phones to make that next online fast-food delivery. Guilty as charged. Sad as it may be, when the exploitive interdependent global food system is out of sight, it’s also out of mind.

As Maya-Ambia puts it,

“the scenario becomes clearer if we consider agriculture as a global system and as a long global value chain, composed of several links where agents interact and connect with the whole economy, nationally and globally. Accordingly, the global economy is formed by a complex web of value chains, whose links are located in different places around the world. Therefore, it is correct to speak of…the global value chain of agriculture that does not begin at the production process, but rather with the appropriation of nature and the transformation of natural objects into economic inputs, including the current land-grabbing in several places by transnational corporations. Driven by profit, these corporations have appropriated land, resulting in disastrous ecological effects.”1

He continues,

“These practices of appropriation and consumption have created a ‘new international division of labor’: the Global South has become the place of appropriation of nature and in some ways a type of dumping ground.”

FAIR TRADE LAY BARE

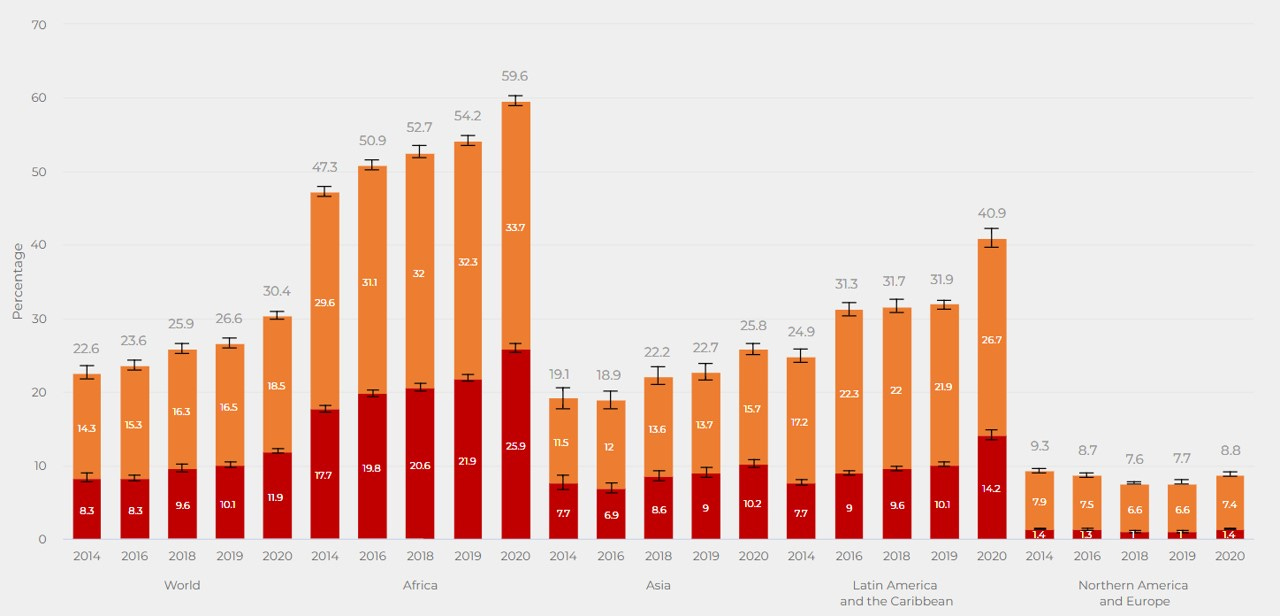

Many of the same places these powerful corporations exploit are also the first to be hit with food insecurity. The United Nations Food and Agricultural Association (FAO) reported last year that “the number of undernourished people in the world continued to rise in 2020. Between 720 and 811 million people in the world faced hunger in 2020.” This includes 480 million people in Asia, 46 million in Africa, and 14 million in Latin America. Food insecurity has been climbing steadily over the last six years. One in three of the world’s 2.37 billion people do not have adequate access to food. This isn’t a supply issue. The world has enough food to feed everyone. This is about fair access.

Many of the same people responsible for producing food exported to more developed countries are the one’s who reap the smallest rewards from the value chain. The smallest share of value goes to those farmers in developing countries. And the smaller the farm, the worse the effect. This fact is revealed by observing stagnating long-run trends of producer prices compared to rising consumer prices. These prices are controlled through governance schemes that squeeze the middle of the hourglass. Firms can exert extreme market power, leverage advanced financial and technological mechanisms, influence local, regional, and state leadership, and assert a particular cultural influence. My Parisian “Le Whopper” influenced the culture of the Champs-Élysées. American fast-food culture in Russia lives on in the new ‘Delicious’ McDonald’s. Full stop.

Inequities are also found in the devastating effects of industrialized agriculture at the hands of these powerful firms. Large swaths of sensitive and diverse habitat in developing countries are violently destroyed – like in the Amazon. They’re making space for more croplands and pastures to grow more food and animals, to make more food products, that are sold to increasingly affluent populations who are rising out of poverty in search of the famed Western consumer lifestyle. This only further destroys the land and water making living conditions in these already poor areas even more stressed. As criminal as it is to live poor in a developed country like the United States, it’s not nearly as worse as living poor in unfairly exploited countries. Especially when it comes to acute food insecurity.

On the other hand, living in developed countries – or desiring to adopt a similar lifestyle – comes with a higher risk of death by obesity…in large part due to fast and junk food. In 2021 the World Health Organization reported that worldwide obesity has tripled since 1975. More people in the world are likely to die of obesity than malnutrition. And because the globalization of high calorie junk and fast-food production exists to drive prices as low as possible, it makes it more accessible to poor people in both developing and developed countries. This puts poorer people at higher risk of both malnutrition and obesity.

Naturally occurring factors, like the pandemic and a changing climate also unfairly impact those most vulnerable. As does war. How naïve to believe countries with a McDonald’s would never take arms against one another; that French fries, freedom fries, would somehow united the world. Russia and Ukraine have proven otherwise. Conflicts in the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America have resulted in millions of people fleeing for safety and starving in the process. Many of whom were farmers. Much of the food needed to feed these refugees historically came from Ukraine and Russia but that is all at risk now.

But American farmers might be able to help. In a rare bipartisan partnership on Capital Hill, just this week President Biden signed into law the Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 2022 (OSRA). U.S. agricultural shippers complained to the federal government that the world’s top ocean carriers unfairly denied them container space. Shippers on the West coast found it more profitable to return empty boxes to Asia so they could be re-loaded for the next round of more profitable exports back to the U.S. Of course, this is all fed by increasing consumer demand by overconsuming Americans. But these interruptions made it difficult for farmers and shippers to predict when their time sensitive goods should be delivered to ports before they spoiled.

But with the passing of this law, ocean shippers are required to report to the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) how many exports they’re loading and from where. The bill also includes rules that determines what makes a denial to export agricultural goods unreasonable. Maersk, Mediterranean Shipping Co., and Transfar Shipping have already offered container space for U.S. agricultural shippers and others are soon to follow. Hopefully, food grown in America can stand a better chance of making it to those in most need in Asia, Africa, Latin America and beyond.

The world seems to be swimming in so many crises that the word has somehow lost urgency. But between war, climate change, and economic inequalities the global food system needs transformation. Here are six ways the FAO believes the global food system could be made more healthy, sustainable, and inclusive:

Integrating humanitarian, development and peacebuilding policies in conflict-affected areas.

Scaling up climate resilience across food systems.

Strengthening resilience of the most vulnerable to economic adversity.

Intervening along the food supply chains to lower the cost of nutritious foods.

Tackling poverty and structural inequalities, ensuring interventions are pro-poor and inclusive.

Strengthening food environments and changing consumer behaviour to promote dietary patterns with positive impacts on human health and the environment.

These steps read a lot like the steps McDonald’s took 32 years ago after entering the Russian market. The introduction of fast-food chains was believed to be a peacebuilding exercise in a conflict-affected area. Freedom fries brought hope and russet potatoes to Russia. McDonald’s scaled up a resilient food system by investing in local farming. They optimized food supply chains within the region. Impoverished Russian’s adjusting to a post communist reality were given jobs growing McDonald’s produce, delivering goods, and working in restaurants. They strengthened the local food environment and changed consumer behavior. And while McDonald’s may not be the healthiest food, not the healthiest habit, it may have been better than what was offered before and it certainly made people happy.

“Delicious and That’s It” just might make it even better. It could be their menu alterations make it a healthier version of McDonald’s. They’ve already made it cheaper. But judging from the Hugo Boss shirt one customer was wearing at the grand opening in Moscow, I have a hunch the new MickeyD’s just might be an elite treat. Still, they may be on to something. Perhaps this is a model that could be used in other places. Maybe more globetrotting fast-food restaurants and junk food producers should be selling out to the locals.

Pizza Hut in Japan already offers squid as a pizza topping, but maybe a Japanese owned franchise would result in even more localized interpretations of a food that originated in Italy. After all, flatbreads exist in a variety of forms all over the world. Imagine مناقيش بيتزا (Manakish pizza), pisa bing 披薩餅 (Bing pizza), or a Catalonia coca? They could all be made with local ingredients, sourced from smaller sustainable farms, sold in locally owned franchises, employing local residents with wages high enough to live on. Who knows where the next Big Mac could be invented? Maybe Russia. Bol’shaya Gov anyone?

Kevin M. Fitzpatrick; Don Willis. A Place-Based Perspective of Food in Society. Chapter 2. Agricultural Industrialization and the Presence of the “Local” in the Global Food World. Carlos J. Maya-Ambía. 2015.