Hello Interactors,

In an era where Western leaders craft policies that oscillate between harsh border controls and selective humanitarian aid, our understanding risks being clouded by data-centric approaches. Through the lens of critical cartography, we see how enhanced data collection can reduce displaced individuals to mere numbers, obscuring their complex human stories behind cold statistics.

Insights into the disorienting effects of domineering multinational capitalism further illuminate how these data practices, though aimed at clarity, often mask the real experiences and struggles of those displaced.

I explore some contradictions in these policies—how they promise to protect yet perpetuate power imbalances, offering a guise of support while fundamentally failing to address the root causes of displacement.

Let’s go…

DISORIENTED BY DOMINANCE

The Dutch government recently took a giant political step to the right. Some say this is as far right as a democratically elected Dutch government has ever been. It’s probably the most intolerant since Hitler installed a Nazi occupation regime from 1940-1945 implementing racist policies which persecuted not just Jews but other minorities as well.

The Dutch government leaned right as recent as 2010-2012, when the right-wing politician Geert Wilders was Prime Minister. Wilders is now back in office, though not as Prime Minister, and has formed a coalition government seeking to implement racist immigration policies that echo an ugly past.

In one of his campaign speeches he said he desires a strict and harsh Netherlands where

"people in Africa and the Middle East will start thinking they might be better off elsewhere".1

Wilders joins the ranks of intolerant European populists like Le Pen of France, Meloni of Italy, and Hungary’s Orban, using anti-immigrant and racist rhetoric as rallying cries. Meanwhile, here in the Americas, Biden and Mexico’s López Obrador have deported tens of thousands of migrants to Mexico despite known risks of kidnapping, extortion, and assault. Biden has been silent on the matter while López Obrador erodes democratic institutions by undermining judicial independence, demonizing critics, and shielding the military from accountability for abuses.2

The EU practices its own repressive transactional diplomacy to evade human rights duties to asylum seekers and migrants — especially from Africa and the Middle East. While numbers fluctuated, there has been a significant overall increase in asylum seeker rates into EU countries since 2010 when Wilders first came to power. That surge was driven by conflicts like the Syrian war, which Western governments were complicit in intensifying, and broader regional instability — including detrimental environmental effects due to climate change.

The Syrian conflict triggered a surge in asylum applications to EU countries, peaking at over 1.2 million annually in 2015 and 2016. Following a dip between 2017 and 2020, applications rebounded to 962,160 in 2022, a 20% increase from 2021, with Germany receiving the most (243,800), followed by France, Spain, Austria, and Italy. From 2010 to 2022, EU asylum applications rose from approximately 259,000 to over 962,000, a near fourfold increase. The primary asylum seekers in 2022 were from Syria, Afghanistan, Turkey, Venezuela, and Colombia.3

It’s curious how fear of immigration coincides with declining EU fertility rates. The average number of children per woman in the EU was 1.46 live births in 2022, well below the rate of 2.1 needed to maintain population levels without migration.

It could be these politicians, and the populist rhetoric they spew, are suffering from a kind of globalist vertigo. As political theorist and Director of the Institute for Critical Theory at Duke University, Frederic Jameson puts it,

“a profound sense of disorientation and inability to cognitively map their position within the larger global system of economic and social relations.”4

As a Marxist, he pins this dilemma on “the immense complexity and abstraction of multinational capitalism.” A primary historical feature of global capitalism is indeed to offload deleterious effects of human labor exploitation and natural resource extraction to regions far from those privileged enough to enjoy the prosperity capitalism can yield. Pushing unwanted labor and development elsewhere is a kind of global “Not-In-My-Back-Yard.” Out of sight, out of mind.

This geographical and cultural distance mirrors the historical migration of freed slaves to the industrial North after the U.S. Civil War. Much like today, these migrants and their descendants faced (and continue to face) a starkly different world of affluence and encountering significant social and economic challenges. History illustrates how geographical and cultural distances can hinder societal understanding and integration, especially when newcomers seek better lives in regions of prosperity.

When those ‘distant others’ appear at the regional doorstep of relative opulence seeking a better life, it can be uncomfortable and disorienting to those who prefer to keep them ‘distant’. In the words of Jameson, it “transcends the individual's limited experiential sphere.”

What may be even harder to imagine is the ’experiential sphere’ most of these people inhabit or inhabited. Much attention is given to asylum seekers beyond their own borders, but most of those ‘distant others’ are forced or choose to stay within, or nearby, their own regions.

A DISPLACEMENT DILEMMA MAPPING THE MASSES

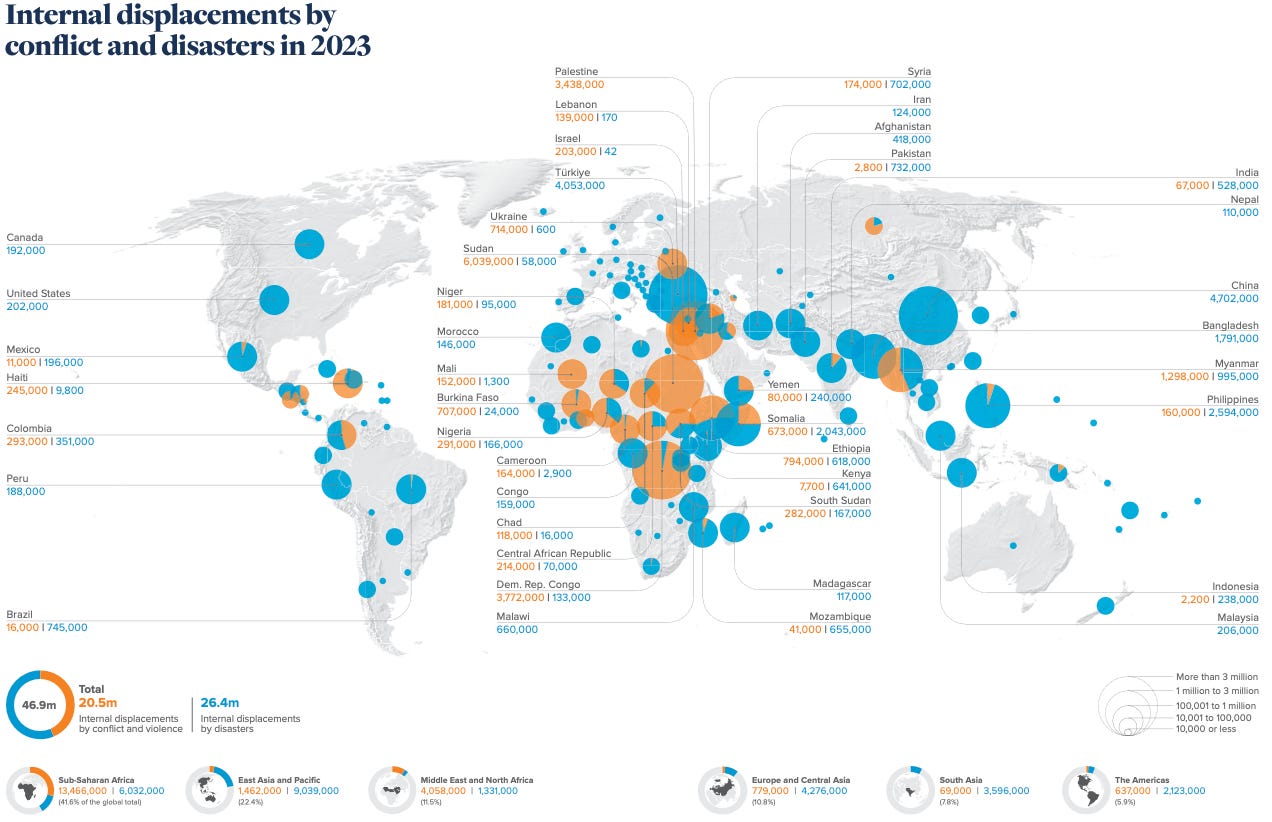

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre's latest report reveals an unprecedented 75.9 million people were internally displaced across 116 countries in 2023, a significant increase from 71.1 million the previous year, driven primarily by escalating conflicts, violence, and disasters in various regions.5

In terms of conflict and violence, the report notes a record high of 68.3 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), with the most affected regions being Sudan, Syria, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Colombia, and Yemen. These countries alone host nearly half of the world's IDPs. The report discusses specific conflicts such as those in Sudan and Palestine, which have led to massive displacement figures due to escalated violence.

Regarding disaster-induced displacement, the report records 7.7 million IDPs attributed to disasters by the end of 2023. It mentions that disasters triggered 26.4 million new displacements in 2023, with significant events occurring in China and Turkey due to severe weather events and earthquakes. The shift from La Niña to El Niño has altered global disaster displacement patterns, particularly affecting the number of people displaced by storms and floods across various regions.

The ’experiential sphere’ is unique as displacement contexts vary in different parts of the world. Sub-Saharan Africa, heavily impacted by both conflicts and natural disasters, remains the most affected region, with increasing frequency and severity of these events. The Middle East and North Africa experienced more displacements, notably from the conflict in Palestine and disasters like earthquakes and floods. Europe and Central Asia saw a significant rise in disaster-related displacements, primarily from earthquakes in Turkey and other natural events, while the conflict between Russia and Ukraine dominated conflict-related displacements. East Asia and the Pacific had the highest global disaster displacements in 2023, with ongoing conflicts like Myanmar exacerbating the situation. South Asia, particularly Afghanistan, faced substantial displacements from both conflicts and natural disasters, with significant impacts on women and girls, highlighting the continuing challenges in the region.

The IDMC report emphasizes the complexity of displacement, where many individuals face multiple displacements due to recurring or simultaneous occurrences of conflict and disasters. It highlights the need for durable solutions and calls for improved data collection to better address needs and facilitate more effective response and recovery efforts. The report concludes with a call for increased visibility and support for IDPs to ensure more sustainable solutions to displacement, stressing the critical role of international cooperation and national governance in mitigating the impact of displacement.

Through a critical cartography lens the call for enhanced data collection risks reducing displaced people to mere data points, stripping them of their individuality and complexities. This data-centric approach, while valuable in assessing the scale and magnitude of suffering (including for essays like this), can lead to surveillance and control, masking the human experience behind numbers and charts.

Frederic Jameson’s critique of the modern world’s disorientation in the face of the negative effects of multinational capitalism also reflects how such data practices might obscure the truth more than illuminate. Jameson might contend that these efforts, while well-intentioned, still fail to construct an accurate mental map of those displaced. Without being on the ground with them, technologies like remote sensing, GIS, mapping, and imaging alone can’t represent an experience that can be cruelly embedded within larger socio-economic systems that contribute to their plight.

Instead of offering clarity, the accumulation of data might reinforce the power imbalances between those with power and money and those without.

GLOBAL GOVERNANCE: GUIDING OR GOVERNING?

The push for international cooperation and governance, as advocated in the IDMC report, could be seen as a continuation of Western dominance under the guise of humanitarian aid. This can perpetuate a form of moral superiority, fostering dependency rather than empowerment, and embodying cultural imperialism that imposes Western values on diverse cultures.

Such humanitarian efforts are frequently designed to align more with the interests and visions of donors from those in wealthier countries, rather than addressing the actual needs of communities in poorer countries and regions. Furthermore, these aid practices can economically benefit the donor countries more than the recipients, sometimes tying aid to the purchase of goods and services from the donor country or using it as leverage to open markets in recipient countries.

The portrayal of aid in media typically emphasizes the generosity and heroism of donors while depicting recipients as passive and helpless. This only further distorts and perverts the complex socio-economic dynamics while undermining the agency of local communities.

These structures often propose top-down solutions that do not align with the needs or the agency of the displaced. They perpetuate a cycle where the root causes of displacement—often tied to the actions and policies of powerful nations—are inadequately addressed.

This critique aligns with Jameson’s observation of a global system where the affluent West remains disconnected from the repercussions of its policies on ‘distant others’, who are left to navigate the dire consequences of conflicts and climate change that are disproportionately caused by those in distant lands of prosperity.

It seems the challenges of addressing global displacement are not merely logistical or political but deeply ideological. What’s needed is a fundamental shift in how data is perceived and used and how international cooperation is structured, executed, and monitored. Only through transformative approaches can we hope to genuinely address the root causes and complex realities of displacement, ensuring solutions that are both just and effective.

Geert Wilders' resurgence signals a concerning trend where Western leaders adopt harsh anti-immigration and asylum policies, paradoxically coupled with a 'white savior complex' towards displaced people within their borders. They assert repressive border control, blocking humanitarian aid while projecting a narrative of benevolence through selective aid packages to 'distant others'.

Ironically, their military interventions, sanctions, and outsized climate change contributions exacerbate displacement crises, yet they deny resultant asylum seekers protection, claiming to 'save' their nations from this self-inflicted burden. Leaders across the spectrum from Biden to Wilders promote a narrative of moral superiority by mapping and surveilling the very displacement their policies precipitate.

This dual approach lays bare a profound hypocrisy at the heart of the Western response to global migration and displacement crises. It illustrates a cavernous disconnect between the root causes we perpetuate and the public stances of moral righteousness we profess on asylum and humanitarian issues.

In confronting this contradiction, we are called to a deeper reckoning — to evolve beyond paternalistic narratives and embrace an ethics of humility, context, and care. True progress demands forging genuine partnerships that respect local cultures, knowledge systems and self-determined priorities. It compels us to support sustainable, community-led development rather than perpetuating cycles of upheaval through military adventurism and plundering the planet's resources.

Only through such a reorientation — by taking full accountability for our complicity while deferring to the resilience and wisdom of those we have displaced — can we hope to transcend the white savior paradigm. In its place, we must cultivate an ethos of global solidarity, one which honors our shared humanity and the inherent dignity of all people, regardless of borders. For it is in this spirit of radical empathy that the path to lasting justice and healing can be found.

“New Dutch government will aim to 'opt out' of EU asylum rules.” Bart H. Meijer. Reuters. May, 2024.

“WORLD REPORT 2024: EVENTS OF 2023”. Human Rights Watch. 2024.

"Now the totality maps us: mapping climate migration and surveilling movable borders in digital cartographies." Bogna M. Konior. Mapping Crisis: Participation, Datafication and Humanitarianism in the Age of Digital Mapping, edited by Doug Specht, University of London Press, 2020.

Global Report on Internal Displacement 2024. Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2024.