Hello Interactors,

Wars, gas prices, eventual food and mineral shortages, inflation, a nagging pandemic, homelessness, immigration, migration, social and economic inequities, rising health prices, home prices, climate change, and natural disasters. What am I missing? Global society needs a hug but we’re all afraid to offer one. We need fixed, I believe, but we are fixed in what we believe.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

TWISTED UP AND HOG TIED

As bombs dropped across Kyiv and surrounding areas last Saturday causing destruction in their path, large missiles were also descending on portions of the state Iowa. These were trees and debris launched by a series of tornados moving at a groundspeed of 45 miles an hour generating winds upwards of 170 miles per hour. They swept across a swath of land 117 miles wide. The storm was rated at a level 4 on a five point scale. Level 4 tornados create devastating damage. Well-constructed houses are leveled; structures with weak foundations are blown some distance away; cars are thrown; large missiles are generated.

This storm swept through the town where I grew up, Norwalk. None of my friends or family were impacted, but seven people died just south of Norwalk in neighboring Lucas County. Another nearby county, Madison – made famous by the book and movie The Bridges of Madison County – was also hit. The National Weather Service said, “This is second longest tornado in Iowa since 1980.”

March is a little early for tornados in Iowa and July is a little late. But last July twelve swept through the state with top wind speeds of 145 miles an hour. And on July 18th of 2018 they had 21 twisters hitting 144 miles per hour.

In 2020 the state was hit with a derecho – a long-lasting wide-spread blast of tornado-level winds that destroyed tens of millions of bushels of corn. Together with the stresses of the pandemic, this event pushed many farmers over the edge. It was enough to prompt Iowa State University to create a program called, “I Worry All the Time: Resources for Life in a Pandemic.” It offers steps to help people answer the question posed by the university’s outreach director, David Brown: “How do we maintain our resilience in the face of these challenges?”

These natural events and human adaptation programs signal what the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) confirms worldwide, “Globally, climate change is increasingly causing injuries, illness, malnutrition, threats to physical and mental health and well-being, and even deaths.” The panel of climate experts warn,

“The extent and magnitude of climate change impacts are larger than estimated in previous assessments. They are causing severe and widespread disruption in nature and in society; reducing our ability to grow nutritious food or provide enough clean drinking water, thus affecting people's health and well-being and damaging livelihoods. In summary, the impacts of climate change are affecting billions of people in many different ways.”1

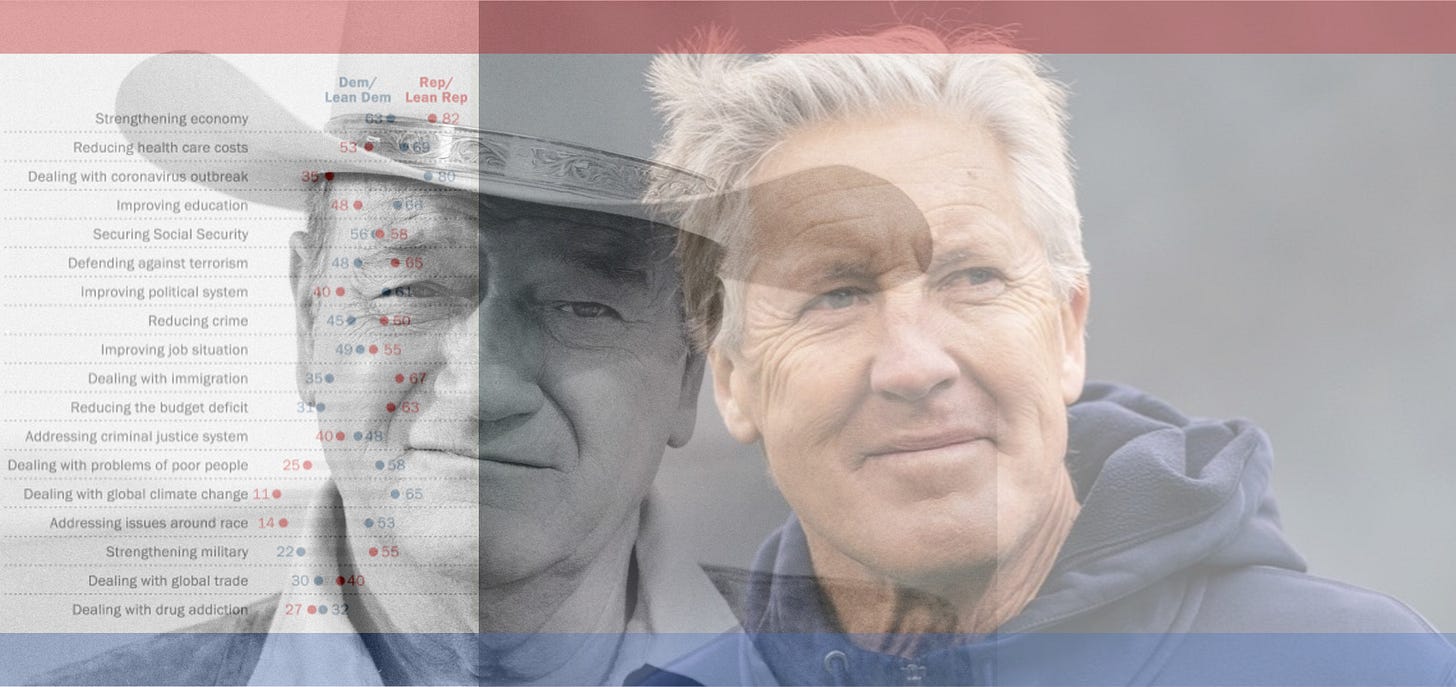

You would think existential threat would be a top concern. Especially among citizens of the United States given our outsized per capita-consumption of energy, goods, and resources. Nope. After President Biden’s recent State of the Union Address, Pew Research reported on a poll taken in January examining American’s views on major national issues.

Seventy-one percent of those surveyed said ‘strengthening the economy’ should be the top priority for the president and Congress to address this year. Second was ‘reducing healthcare costs’ at 61 percent. ‘Dealing with climate change’ came in 14th out of 18 topics with 41 percent believing it is something government should address.2

Survey participants who lean both politically Left and Right believe the economy is most important. Though, Republicans believe it more than Democrats. But not my much – 82% versus 62%. A 20 point difference. But on climate change the differential is the largest of all 18 issues surveyed. Only 11% of Republicans surveyed believe the government should prioritize reducing effects of climate change versus 65% of Democrats. That’s a 54 point difference in opinion.3 This suggests that of all the things Americans are divided on, the one that poses the biggest threat is the one with which we differ the most.

This survey targets adults age 18 living in the United States. I’ve been thinking about those youngest and oldest surveyed. I try to imagine what effects climate change will have on them in 20 years. The IPCC paints a grim picture. They created three periods of time that reflect what life will be like on planet earth given where we are today.

The three periods are near-term (up to 2040), mid-term (2041-2060), and long-term (2061-2100). By 2040, the near term, a good chunk of the upper end of baby-boomers (who dominate federal government) will be dead or nearing death. Those ages 18 today will be 36 in 2040. The year 2100 seems far off, but if that 18 year old is lucky they’ll be 96 in 2100. A child born today will be 78 years old.

They’ll read about those suffering Iowa farmers devastated by natural disasters, economic hardship, and a pandemic with envy. The IPCC says

“children aged ten or younger in the year 2020 are projected to experience a nearly four-fold increase in extreme events under 1.5°C of global warming by 2100, and a five-fold increase under 3°C warming. Such increases in exposure would not be experienced by a person aged 55 in the year 2020 in their remaining lifetime under any warming scenario.”4

We are most likely too late to avoid this reality. The focus now is on adaptation. Our multi-legged, winged, and gilled friends are already trying. There is ample evidence of species climbing to higher land, shifting to cooler regions, or diving to greater depths in the ocean. This will have ripple effects throughout the ecosystem on which every living being relies – including humans. We have the mental capacity to do more than other animals than just adapt, but appear unable to do so.

The IPCC says, “Adapting successfully requires an analysis of risks caused by climate change and the implementation of measures in time to reduce these risks.” They ask these five questions:

Is there an awareness that climate change is causing risks?

Are the current and future extent of climate risks being assessed?

Have adaptation measures to reduce these risks been developed and included in planning?

Are those adaptation measures being implemented?

Are their implementation and effectiveness in reducing risks monitored and evaluated?

On the first they claim there is increased awareness that climate change is causing these risks. Anecdotally, I see historically climate denying institutions, companies, and individuals calling for adaptation and mitigation strategies and technologies. It’s hard to say how many of them are acknowledging climate change out of fear or just seeking financial gain. Like our healthcare industry, many see opportunity in human suffering as a result of climate change.

But the IPCC also says “given the rate and scope of climate change impacts, actions on assessing and communicating risks, as well as on implementing adaptation are insufficient.” These IPCC reports can’t get any more direct. They conclude,

“The scientific evidence is unequivocal: climate change is a threat to human well-being and the health of the planet. Any further delay in concerted global action will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a livable future.”5

GET ALONG LITTLE DOGGIE

Norwalk, Iowa is home to two movie star super-heroes, the lead in “Aquaman” Jason Momoa and Brandon Routh who played Superman in “Superman Returns”. Another famous actor was born in nearby Winterset, Iowa in Madison County – home of the covered bridges. His name is John Wayne.

Or Marion Morrison, as he would have been known back in Winterset. His family moved to California when he was nine. He got the nickname ‘Duke’ when a local fireman started calling him ‘Little Duke’ after frequently seeing him walking his dog, Duke. ‘Duke’ sounded better than Marion and soon everyone was calling him by his nickname, Duke. His stage name, John Wayne, came with his first leading role in the 1930 film The Big Trail.

John Wayne claims to have been a socialist while attending USC pre-law, voted for FDR in 1936 and supported Woodrow Wilson. But by 1944 he became concerned with communism and helped create the politically conservative organization Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. He and its members believed the motion picture industry, and the country, was being infiltrated by communists.

But critics said the organization sympathized with fascists, was anti-Semitic, against unionization, and endorsed the Jim Crow laws of the South. It broke up in 1975, but by then John Wayne’s views were well publicized. He told Playboy magazine in 1971 that

“I believe in white supremacy until the blacks are educated to a point of responsibility.”6

And it’s fitting he often played a cowboy because he believed America was not

“wrong in taking this great country away from the Indians. Our so-called stealing of this country from them was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed new land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.”7

Playing leading roles as both cowboy and war hero, John Wayne became the symbol of American exceptionalism, individualism, strength, and masculinity. When Kirk Douglas played the role of Vincent van Gogh in a 1957 film Wayne told him,

“Christ, Kirk, how can you play a part like that? There's so goddamn few of us left. We got to play strong, tough characters. Not these weak queers."8

On welfare John Wayne said,

“I'd like to know why well-educated idiots keep apologizing for lazy and complaining people who think the world owes them a living.”9

Ronald Reagan was a close friend of John Wayne. They were both actors, shared conservative worldviews, and had a shared vision for the American ideal that each of them personified. They remain idols of the Republican party to this very day. I’m guessing roughly one-third of the country still align to their worldview. It’s a view that holds hierarchy and authority, usually male authority, in high regard. They believe individuals control their destiny, government should not hold them back, and are skeptical of what John Wayne called ‘well-educated idiots.’

This would likely include the scientists who authored that IPCC report I keep quoting. By extension, they are largely skeptical of the risks of climate change. And they see attempts by the UN, EU, or any governmental agency to enact mitigation measures as impeding individual, industry, and economic progress.

But those who favor a more egalitarian and communitarian worldview see many of these strict social hierarchies and entrenched capitalistic traditions as the sources of social, economic, and environmental inequities and destruction. They seek restrictions on individual gluttony, corporate excesses, and industry exploitation.

This group, often characterized as ‘The Left’, tend to believe that if they could just ‘educate’ the public, especially their counterparts, ‘The Right’, they’d come to realize the threat that we face. They’re convinced education is the answer. Clearly this isn’t working.

In 2012 a group of scientists decided to test this education theory. What they found is that not only is the theory wrong, but that

“Members of the public with the highest degrees of science literacy and technical reasoning capacity were not the most concerned about climate change. Rather, they were the ones among whom cultural polarization was greatest.”10

We believe what we want to believe based largely on which crowd we want to be affiliated with and experts are not immune. And ordinary people on both ‘The Left’ and ‘The Right’ use the best available science to justify their beliefs. And the more knowledge we accumulate the more entrenched we become.

This study confirms what others have shown which is we are polarized in our beliefs about climate change. But it also reveals that those who claim to be politically ‘moderate’ or ‘centrist’ don’t necessarily share worldviews despite be co-located on the political spectrum. Those who ‘lean Republican’ or are ‘slightly conservative’ and those who are ‘Independent’, ‘lean Democrat’, or are ‘slightly liberal’ showed their respective opinions on climate risk were exceedingly different than those claiming to be decidedly ‘conservative Republicans’ and ‘liberal Democrats.’

In other words, their study suggests polarization isn’t just about Republicans and Democrats, Liberals and Conservatives, or the Far Right and Far Left, it’s about our individual worldviews and the communities we pick. And, importantly, what opinions members of those communities deem acceptable to believe and communicate. The risk of be ostracized by your in-group is so great that we resist admitting we may agree with some of what the out-group believes – even if deep down we believe it to be truthful.

Here’s an extreme example inspired by the study. Imagine a diehard Republican Iowa farmer, Scott, who lost a family member in one of those tornados. Perhaps he heard of a farmer friend of a friend who had crops damaged by those storms in 2020 and became bankrupt. Scott may have become so troubled and anxious that he even attended one of those therapy sessions Iowa State University holds.

Somehow these unfortunate life events eventually convinced him climate change is real, but he largely keeps his opinion to himself for fear of not fitting in. Then one day he gets invited to go on a hunting trip in North Dakota by an old high school friend who works on a fracking rig. There he is surrounded by his buddy’s work pals, oil guys, talking shit about liberals who get riled up over climate change. How likely is Scott to admit to these guys that he believes in climate change? It makes no difference that he’s a Republican or they are, he knows it’s his clan and he knows the social cost of speaking his mind. He knows climate denial is part of what keeps him in the club.

On the other side, the environmental science community and some activists, across the mostly liberal spectrum, are splintering over mixed worldviews on energy policy. Many environmental scientists weigh the risk of human lives due to climate change against accidents from nuclear energy reactors and are coming out in support of nuclear energy. They get skewered on Twitter for advocating in favor of nuclear power even though they’re doing it in the name of saving lives and the planet. The “No Nukes” movement of the 70s is so strong to this day among the environmentalist crew that anybody who dares to say “Yes to Nukes” is shamed, blamed, and defamed.

It turns out that when we feel bounded in our rationality, we are really good at seeking knowledge to unbind it. Psychologists and sociologists called it ‘motivated cognition’. Our memory does it on our behalf. For example, we tend to remember our successes more than failures. And if a recollection of an event doesn’t match our current worldview, we’ll unknowingly reshape the memory to suit our current motives.

We also tend to preference and ingest new and novel information when it suits our immediate interest and desires. We tend to want to believe a study even when we know the sample size is too small or is poorly designed. This makes bite sized social media fed by our social feeds perfect appetizers for the full meal deal found in a longer article, news report, podcast, or talk show.

But this study – that my own motivated cognition led me to – points to an even more weighty form of cognition: ‘cultural cognition’. This theory is frequently used to better understand how we evaluate risk. It states that our personal values are what lead us to seek facts so we may conduct our own risk analysis. And we are more likely to believe what our in-group wants us to believe than what may actually be true.

LOVE ‘EM UP

We live in a diverse society of conflicting opinions. For us to minimize the effects of climate change, to make kids born today not suffer more than they have to, we’re going to have to come together now. Yesterday.

So what do we do? Sadly, there are more studies identifying these behaviors and theories explaining them then there are confirming solutions. But the authors of the study offer a clue. It has to do with minimizing the self-threat people feel when confronted with information they disagree with…or more specifically, with opinions and knowledge they deem representative of the out-group.

When we are presented information that affirms our beliefs, we use that as evidence to bolster our position in our in-group. This is referred to as self-affirmation bias. It’s what keeps us polarized in our camps. It makes us feel good and raises our self-esteem. But there are many things that can raise our self-esteem that aren’t related to our consumption of self-affirming sound bites.

When we’re presented with information that feeds our self-affirmation bias we have a choice to make. We can gobble it up as another self-esteem boost or we can interrogate, question, and evaluate it. We have agency to choose whether this is true or not or even worthy of consideration.

And studies have shown that the best way to get ourselves in this frame of mind is to find another way to boost our self-esteem before consuming the information. Just by writing down one thing that we value about ourselves or others value in us is all it takes. That self-esteem boost is sufficient enough that we loose the craving for that self-affirming nugget of information being fed to us from members of our tribe.

For example, in one study they found

“a capital punishment proponent should feel more open to evidence challenging the death penalty’s effectiveness if he or she feels affirmed as a good friend or valued employee. Self-affirmations, [they] argue, trivialize the attitude as a source of self-worth and thus make it easier to give up.”11

This reminds me of the Seattle Seahawks head coach approach to coaching. Pete Carroll is known for signing players who excelled at one position in college or professionally and then convincing, converting, and committing them to become equally proficient, or more, in a different position. They are invariably resistant. After all, they have their ego, identity, and paycheck wrapped up in their history as a certain kind of player in a particular position. They’ve even created their own in-group fan club they don’t want to disappoint.

Carroll’s solution is very easy and unorthodox for a football coach. Instead of focusing on what new skills they need to learn, an anxiety he knows they already possess, he reminds them of what they’re good at. He builds up their self-esteem by focusing on them as humans or on their athletic skills unrelated to the position. As Pete says, “I love ‘em up.”

He finds that within a short time they are the ones that come to him saying, “Coach, I think I’m ready to try that position.” He barely has to mention it. By boosting their self-esteem Coach Carroll puts them in a frame of mind whereby they no longer need to rely on their ego boosting, self-affirming biased past to feel good about themselves. And, by in large, they’re better for it.

This demonstrates that we need not wait for others to find alternative ways to build self-esteem. When confronted with people who you find resistant to your position on issues to do with the environment, economy, or equity try offering them a compliment. Maybe ask them what makes them feel good in the world. Ask them what they like doing, what they’re good at. Maybe even ask them what they fear.

You’ll be triggering pangs of self-esteem in them. You’ll be reminding them of how special they are. And let’s face it, we’re all special and we’re all afraid of something. My experience is that when I do, I may not win them over right there and then – or ever – but I just might find what we have in common. You may find, as I have, that just by this act you’ve boosted your own self-esteem such that you may be open to their opinions.

I wonder what would happen if our friend Scott, the right-wing farmer in Iowa, reminded a couple of those North Dakota frackers what makes them special. Maybe it’s a hidden talent, hobby, or award they earned at work. And I wonder if in doing so he would have found an opening to ask them about what they really felt about fracking, fossil fuel, and the impact it was having on the land they were walking on and the animals they were hunting. For all we know, they’re all afraid of the effects of climate change but fear the backlash from their peers more than the world ending.

The latest IPCC report emphasizes the complexities surrounding the interaction of people and place and the role these interdependent interactions play in the cause and effects of climate change. They write, “This report has a strong focus on the interactions among the coupled systems climate, ecosystems (including their biodiversity) and human society. These interactions are the basis of emerging risks from climate change, ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss and, at the same time, offer opportunities for the future.”

They go on to state that “Human society causes climate change…impacts ecosystems and can restore and conserve them.” [my emphasis] They also remind us that

“Meeting the objectives of climate resilient development thereby supporting human, ecosystem and planetary health, as well as human well-being, requires society and ecosystems to move over (transition) to a more resilient state.”12

A sizable chunk of disadvantaged members of our global community have been forced into a perpetual and exhausting resilient state for centuries. All at the hands of generations of a relatively small advantaged few. The outreach director at Iowa State asked weary farmers, “How do we maintain our resilience in the face of these challenges?”

Our increased polarization is taxing the resiliency of our respective out-groups. It’s time we restore and conserve them, embrace the diversity of opinion, recognize all worldviews are coupled systems that make up the messy but necessary human condition. Yes we have a climate crisis, but we also have an empathy crisis. Planetary health starts with mental well-being. Let’s boost our own self-esteem, the esteemed members of our clan, and even those you can’t stand. Those born today will appreciate it when they’re your age.

Overarching Frequently Asked Questions and Answers. Sixth Assessment Report. IPCC. February 2022.

State of the Union 2022: How Americans view major national issues. Katherine Schaeffer. Pew Research. February 2022.

Ibid.

(1) IPCC.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Kahan, D.M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L.L., Braman, D. & Mandel, G. Nature Climate Change 2. 2012.

When Beliefs Yield to Evidence: Reducing Biased Evaluation by Affirming the Self. Geoffrey L. Cohen, Joshua Aronson, Claude M. Steele. 2007.

(1) IPCC.