Hello Interactors,

Happy winter solstice!

Today, the northern hemisphere experiences its shortest day and longest night, a celestial event rooted in the planet's axial tilt. This seemingly simple astronomical fact has profound implications for economic geography. It influences everything from agricultural productivity to social traditions of sharing and reciprocity.

SOLSTICE AND SHARING

I recently visited the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre at Whistler. These two tribes are part of the Squamish River watershed that flows into Howe Sound, a fjord located just around the corner from Vancouver, British Columbia. This watershed is central to their traditional territories and plays a vital role in their culture and economy.

From an economic geography perspective, the tilt of the earth underpins the seasons and, by extension, patterns of production and scarcity that shape human economies. In regions where winter brought agricultural dormancy, societies had to develop systems to store, preserve, and share resources to survive until the next growing season.

The winter solstice symbolizes the end of this scarcity. It promises returning light, a pivotal moment in the annual cycle for societies historically reliant on natural rhythms. For the Squamish and Lil’wat peoples, this period was a time of reflection, gratitude, and redistribution. Ceremonial gatherings and potlatches reinforced community bonds by ensuring that the resources harvested in times of plenty were shared equitably during the lean winter months.

I saw evidence of these community bonds at the cultural center. The five visitors from West Virginia and myself, were the only white folks in the place. I was happy to see and hear a group of teen Squamish or Lil’wat boys gathered, talking, and giggling. There was a table of older Indigenous women sharing tea and treats. I asked one of our guides if she was doing anything special for the upcoming holiday. She said, “Well, I have presents for my mom’s side, but not my dad’s. And I have presents for half my siblings, but not the other half! So, it looks like that’s what I’ll be doing!”

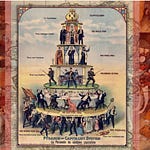

Practices of reinforced social cohesion and mitigating disparities can be seen in both Indigenous and early European traditions. These lessons of reciprocity and redistribution remain vital amidst the gulf between extreme wealth and pervasive poverty. That too became apparent during my visit.

As I was browsing the gift shop, I overheard an Indigenous employee ask a friend, “How has work been?” Her friend responded, “It’s ok. This time of year comes with a lot of Christmas clean ups, people getting their Whistler places ready…it’s hard work, but good money.”

As we mark the winter solstice and conclude this fall series on economic geography, it is worth considering how the natural cycles dictated by the earth’s tilt continue to influence modern economies. Even in an age of surplus for some, the rhythms of scarcity and abundance persist, challenging us to find equitable ways to share resources.

The traditions of the Squamish, Lil’wat, and countless other cultures remind us that sustainability and justice are not just matters of economic policy but also of values deeply connected to the natural world. This solstice invites us to honor those lessons, seeking balance and light amid the darkest days.

The widespread, worldwide post-harvest behavior — like the Squamish and Lil’wat spiritual renewal through prayer and ceremonies; the community bonding with feasts, potlaches, and storytelling; the observance or celestial cycles and gratitude for earth’s gifts; and the artistic creations for ceremonial dances and rituals — has been happening for millennia.

SATURN AND THE GREEK SAINT

I thought I’d reshare a relevant excerpt from a post I did a few years ago that explores the roots of Christmas. It started with a communal approach to abundance with celestial-triggered ancient traditions like Saturnalia in Rome. Saturn, the god of agriculture, inspired events where feasts, gift-giving, and the symbolic inversion of roles served to address the inherent inequalities of agrarian economies.

“It was so baked into the fabric of society that even the church began painting it with Christian imagery and metaphor. Because the celebrations occurred on or around the end of November and into December there were many elements of Christianity to which they could attach the events.

During Roman times, December 17th marked the day of the Saturnalia – a festival honoring the god of agriculture, Saturn. All work halted for a week as people decorated their homes with wreaths. They shed their togas to dawn festive clothes, and they drank, gambled, sang, played music, socialized and exchanged gifts. It was a celebration of their agrarian bounty and the return of light at Winter solstice. It was also a time to invite their slaves to dinner where their masters would serve them food.

One Christian Saint affiliated with early December – and the one most honored today in the form of a plump jolly man wearing a red velvet suit – is Saint Nicholas. December 6th is St. Nicholas Day. For many European countries this marked the official end of the harvest season. And even today it’s recognized in some countries as a kind of warm-up act to the more official and accepted Christmas day, December 25th.

Nicholas of Bari was a Greek Christian bishop from modern day Turkey. Also known as Nicholas the Wonderworker, he earned a reputation during the Roman Empire for many miracles; all of which, were written centuries after his death and thus prone to exaggeration. But he was most famous for his generosity, charity, and kindness to children, the poor, and the disadvantaged. He was said to have sold his own belongings to get gold coins that he’d then put in the shoes outside people’s homes. This is the origin of the tradition of putting shoes or stockings out on Christmas Eve.

They say he also saved the lives of three innocent men from execution. He chastised the corrupted judge for accepting a bribe to execute them. And he certainly would have been watching over the peasant farmers and slaves to insure they were treated fairly. He seemed to always have an eye out for inequities and justice for common people. Maybe that’s what made him a saint. Or maybe he was just born that way. After all, Nicholas in Greek means “people’s victory.”

The Puritans obviously lost at their attempts to ban Christmas. Lacking any evidence from the Bible, the Christian powers that be eventually settled on the 25th of December as the day Jesus was born. They most likely picked the 25th because that was the day winter solstice landed on the Roman calendar.”

Happy solstice, everyone. Whether from St. Nick or the Squamish ways,

let’s remember through these darkest days: sustainability and justice aren’t just decree, they’re rooted in values that connect you and me.