Hello Interactors,

Since his return to office, Trump hasn’t just taken power — he’s trying to reshape the landscape. From border crackdowns and sick real estate fantasies to federal purges by strongman stooges, his policies don’t just enforce control — they seek to redraw the lines of democracy itself.

Strongmen don’t wait for crises — they create them. They attempt to manipulate institutions, geographies, and public trust until there’s so much confusion it makes anything they do to ease it acceptable. I dug into how authoritarianism thrives on instability and contemplate some ways to alter it.

DEMAND DOMINATION THROUGH DOUBT AND DISORDER

I was once a strongman, or at least I could summon one when needed. I could override the part of my brain that protects me from injury and tap into something primal — something that made me feel invincible. A surge of adrenaline convinced my brain I could not only hurl myself into another person but through them, painlessly.

I played rugby. What I experienced is known as Berserker State, or berserkergang—a shift in brain activity and hormone surges that cause extreme arousal and altered perception. Rugby is a sport where people spend over an hour pretending they’re not hurt. That’s in contrast to soccer, where people spend over an hour pretending they are. 😬 But while rugby is violent, it’s not played with violent intent. Players may be tough, but they don’t seek to hurt each other — at least, not permanently.

That’s in stark contrast to figures like Trump or the new FBI deputy director, Dan Bongino — men who cultivate a different kind of "strongman" identity. They like to wield aggression not as a tool for sport, but as a weapon against others. Bongino is a tough guy on steroids — literally, or at least he acts like it. His wide-eyed rage on his online show suggests a performance of strength, a constant need to assert dominance.

But people like Trump and Bongino weren’t born this way; they were molded by insecurity, myths, and a long history of toxic masculinity.

Psychologist Brian Lowery challenges the idea that identity is something stable and fixed. Instead, in his 2023 book, Selfless, he argues that identity is socially constructed—shaped by interactions, cultural narratives, and institutions. In times of stability, people feel secure in who they are.1 But when faced with economic instability, cultural shifts, or political crises, identity becomes fragile and unstable. Some people lash out. Some, like myself on the rugby field, may go berserk. Others — like Trump and Bongino — build their entire personas around control. In the end, it’s just bluster, bravado, because they behave like a jerk.

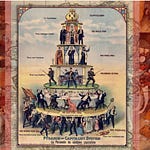

Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman takes this argument further, showing how growing inequality and precarity drive people toward authoritarianism and fundamentalism. When the world feels chaotic, strongman leaders and rigid ideologies provide the comforting illusion of order and control — even if they fail to address the root problems. Bauman warns that these leaders scapegoat the vulnerable, suppress truth, and mystify the real causes of inequality — all while presenting themselves as the only force capable of restoring stability.2

But authoritarianism isn’t just about psychology — it’s also shaped by real-world conditions. Geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues that authoritarian rule isn’t just about individual strongmen — it’s embedded in systems that use violence and spatial control to uphold racial and class hierarchies.3 Identity insecurity isn’t just a feeling; it’s a reaction to real structural forces like economic displacement, aggressive policing, and militarized borders. Strongman leaders don’t just exploit insecurity — they thrive where instability is built into everyday life.

In 2020 Journalist Shane Burley examined how white nationalist groups tap into these anxieties, embedding themselves in mainstream politics by offering disaffected individuals a sense of belonging through authoritarian ideologies.4 The Alt-Right doesn’t just recruit based on political beliefs — it recruits based on a fear of displacement and loss. Authoritarianism isn’t just ideological; it emerges from instability, reinforced by systems of control like aggressive policing and restrictive immigration policies.

Strongmen don’t just seize on fear — they stoke, sculpt, and steer it, spinning crises into control. Through media manipulation and crisis narratives, they mold public perception and then mandate obedience.

SPINNING STRIFE INTO SUPREMACY

Once fear is felt — it can be harnessed. Political elites capitalize on uncertainty, framing crises in ways that make authoritarian measures seem necessary. Feldman & Stenner, political psychologists specializing in the study of authoritarianism and ideological behavior, argue that authoritarian attitudes intensify when people perceive instability, whether real or exaggerated.5

Their research highlights how threat perception — not just personal ideology — activates authoritarian tendencies, leading individuals to prioritize conformity, obedience, and strong leadership in times of social or political uncertainty. By defining threats and controlling the narrative, leaders turn uncertainty into urgency, making repression feel not only justified but necessary.

Crisis narratives work because they reshape reality. Right-wing populists blame immigrants, global elites, and cultural change, painting national identity as under siege. Meanwhile, progressive authoritarian movements often frame reactionary forces, corporate elites, and slow-moving institutions as existential threats, demanding immediate, drastic action.

Mikhail Bakunin, a 19th-century anarchist and revolutionary who was both a friend and fierce critic of Karl Marx, warned that revolutionary leaders who claim to act in the people’s name often end up seeking power for themselves. He accused Marx and Engels of designing a system where they, not the workers, would ultimately rule. In 1873 he wrote,

“The Marxists maintain that only a dictatorship—their dictatorship, of course—can create the will of the people, while our answer to them is: No dictatorship can have any other aim but to perpetuate itself.” 6

Both right and left-wing authoritarianism use fear to rally supporters, silence opposition, and create a sense of emergency where only their leadership can restore order.

Media control plays a key role in reinforcing these crisis narratives. In 2019, it was exposed how Trump advisor Stephen Miller deliberately inserted white nationalist rhetoric into U.S. policy. He used far-right media to amplify unverified crime statistics and frame immigration as a civilizational threat.7 This wasn’t just ideological posturing — it was a calculated effort to embed fear into governance, making xenophobia a political weapon.

But crisis narratives don’t just shape perception; they translate into policy. ICE raids and the Muslim ban turned entire communities into symbols of danger, reinforcing the idea that certain groups are inherent threats. Militarized borders, aggressive policing, and detention centers didn’t just enforce laws — they reinforced the notion that outsiders must be feared. The state stands as fear’s fierce enforcer, embedding oppression in order and power in place.

This dual strategy — controlling the narrative and enforcing it through space — creates a self-reinforcing cycle. When people see more policing in "dangerous" areas, they assume the danger was real all along. When borders become militarized, they don’t just frame outsiders as threats — they enforce state power over Indigenous lands.

The U.S. foundation stands on the reservation system, the suppression of the American Indian Movement, and the crackdown on Standing Rock from 1890 to 2016. This is how authoritarianism isn’t just imposed — it’s sustained. Fear becomes a governing principle, and governance becomes a system of control. Crises are never solved — only maligned, magnified, or momentarily managed.

BREAKING THE CYCLE OF CRISIS AND CONTROL

Authoritarianism feeds on instability. It thrives in moments of crisis, when people feel insecure about their place in society, fearful of rapid change, and unsure of who to trust. As historian Alexandra Minna Stern shows in Proud Boys and the White Ethnostate, far-right groups have mainstreamed authoritarian rhetoric, repackaging extremism as populist conservatism and framing strongman rule as the only defense against societal collapse.8 But authoritarianism is not confined to one ideology. Different movements, across the political spectrum, use crisis narratives to justify coercion.

Some frame threats as coming from the outside, while others see danger emerging from within. But the burden of these crisis narratives is not evenly distributed — the historically marginalized powerless pay the price when panic fuels policy.

Nationalist movements depict outsiders — immigrants, racial minorities, queer communities, and religious groups — as existential threats. Border militarization, mass surveillance, and authoritarian crackdowns are justified as necessary to preserve “national security” and maintain cultural homogeneity. These policies disproportionately harm those already marginalized. They deepen structural inequalities through exclusion, criminalization, and violence.

Radical movements on the left often focus on reactionary forces — corporations, conservative institutions, or privileged elites — as dangers to progress. While calls for justice are vital, ideological purity tests and coercion can sometimes alienate marginalized activists. People of color, queer individuals, and various other members the poor working class are forced to navigate rigid expectations. They’re not always accepted or embraced for their own lived experience and material struggles.

While both reactionary nationalism and ideological rigidity can rely on crisis-driven politics to justify control, the scale, methods, and impact differ. Authoritarianism, in any form, thrives by exploiting social fractures — especially those along lines of race, class, and identity. Resisting this requires dismantling not just strongmen but the very conditions that allow these crisis narratives to justify exclusion and repression in the first place.

Instead of centering political resistance around individual leaders, what if democratic societies addressed the root causes that make authoritarianism attractive or inevitable. That would require focusing on solutions that break the cycle of crisis-driven politics.

We need pluralistic national identities that aren’t rooted in exclusionary fears.

I can imagine a stable democracy that creates belonging without requiring an enemy. But too often, we’ve seen reactionary nationalism frame identity through exclusion —out-groups are viewed as threats to be feared. At the same time, skewed ideological purity tests along a spectrum of progressive movements can create new kinds of exclusion, pushing aside marginalized activists who don’t perfectly conform to rigid political expectations — a fate and flaw of America’s binary governmental system.

What if, instead, national identity was rooted in civic participation, shared democratic values, and social trust? Imagine a society where people feel secure in their belonging — where they are less susceptible to politicians or movements that demand fear-based loyalty.

The weakening of democratic institutions allows more authoritarianism to creep in under the guise of stability. Like DOGE. We’ve seen it happen elsewhere: courts stacked with political loyalists, journalists jailed or silenced, maps gerrymandered, or elections rigged under the pretense of "security."

When institutions are compromised, strongmen don’t need to overthrow democracy outright with tanks in the streets and MAGA banners unfurled at the White House — they dismantle it from within. Hitler’s rise in 1933 didn’t begin with a coup but with the erosion of institutional checks — using crises like the Reichstag Fire to justify emergency powers, purging opposition, and bending the judiciary to his will. Strengthening judicial independence, free media, and election protections ensures that bad political actors — and their enablers — can’t weaponize fear to dismantle democratic norms.

Economic insecurity is one of authoritarianism’s most powerful recruiting tools. When people can’t afford rent, healthcare, or basic necessities, the appeal of a leader who promises order — no matter the belief or the cost — grows stronger. But anyone who’s ever tried to grow a plant knows that real long term security for growth comes not from repression but from investment. Here are a few examples:

Denmark’s “flexicurity” model protects workers by ensuring job loss doesn’t mean desperation, balancing labor rights with economic adaptability.

Finland’s universal basic income pilot tested how direct financial support can reduce crisis-driven populism.

Portugal’s harm reduction approach to drug policy shows that community-driven safety programs reduce crime more effectively than militarized policing.

We can’t afford to keep fighting authoritarianism after it takes hold — we must build a society where it has no room to grow. The best barrier to crisis-fueled control is building a world where crisis takes no toll. When fear isn’t fed and panic isn’t planned, strongmen lose their grip on the land.

Rugby, like any sport, taught me that rules aren’t just constraints — they’re what make the game possible. Without them, it’s not a sport, just a free-for-all where the strongest dominate. But rules alone aren’t enough. The game works because players believe in them, because they trust that everyone is playing under the same conditions, that power has limits, and that fairness is enforced.

Democracy isn’t so different. It’s not just laws or institutions that hold it together — it’s the shared belief that the system works well enough to be worth preserving. But what happens when people stop believing that? We can see what happens when people think (or know) the game is rigged, that the rules only serve the powerful, or that breaking them is the only way to win.

That’s when authoritarianism thrives. It doesn’t rise because people love oppression — it rises because people fear disorder more than they fear control. When strongmen present themselves as the only ones who can restore stability, they’re assuming we’re willing to sacrifice a few freedoms along the way.

The strongman’s power isn’t just enforced by words — it’s mapped onto other countries, cities, borders, and institutions. As Indigenous and Black resistance scholars reminds us, control isn’t only about who governs — it’s about who is allowed to move, who is confined, and whose communities are turned into sites of surveillance and fear. When authoritarian leaders redraw the boundaries of belonging, they don’t just control laws; they control the ground people stand on.

So, the real question isn’t just how to resist authoritarianism. It’s how to ensure people don’t give up on the game altogether. How do we build a society where order doesn’t require coercion, and freedom doesn’t lead to chaos?

There’s obviously no single answer, but maybe it starts with refusing to let fear dictate our choices. Democracy shouldn't be about choosing between control and collapse — it should be about maintaining the fragile, necessary balance between them. And that balance isn’t automatic. It’s something we have to constantly pr

minnotect, defend, and — when needed — rebuild, brick by brick, border by border, rule by rule…without being a jerk or going berserk.

Lowery, B. S. (2023). Selfless: The Social Creation of You. HarperOne.

Bauman, Z. (2016). Strangers at Our Door. Polity Press.

Gilmore, R. W. (2022). Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation. Verso Books.

Burley, S. (2020). The Autumn of the Alt-Right. Commune Magazine.

Feldman, S., & Stenner, K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 18(4), 741-770.

Bakunin, Mikhail. 1873. Statism and Anarchy. Translated by Marshall S. Shatz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Hayden, M. E. (2019). Stephen Miller’s Affinity for White Nationalism Revealed in Leaked Emails. Southern Poverty Law Center.

Stern, A. M. (2019). Proud Boys and the White Ethnostate: How the Alt-Right is Warping the American Imagination. Beacon Press.

(more references available upon request…they don’t always fit the length allowed)