Hello Interactors,

This post is part of a three week experiment. I’ve divided my topic into three parts each taking a bit less time for you to read or listen. They each can stand on their own (maybe), but hopefully come together to form a bigger picture. Please let me know what you think.

Maps are such a big part of our daily lives that it’s easy to let them wash over us. But they’re also very powerful forms of communication that require our attention and scrutiny. If we don’t, we run the risk of being hypnotized and even deluded.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

Someone posted a map on Facebook recently showing just how close Russia is to Alaska. The post read, “This should make you 😳 America. My kids were not taught as much geography and history as I was growing up. This probably needs to be shared to remind us all. For those who think Russia is all the way on the other side of the world [it is] only 53 miles at the Bering Strait’s narrowest point. Like us driving from Cedar Rapids to Waterloo.”

The comments to the post echoed this worry with words like, “Too many don’t realize this.”; “There are small islands 25 miles apart.”; “OOOOOOOOO scary.”; and “I’ll admit that I didn’t realize this.”

They probably didn’t realize this either: the United States and Russia not only share the largest maritime border in the world – a line stretching 1600 nautical miles dividing the Chukchi Sea to the north and the Bering Sea to the south – but it cuts straight through two islands called the Diomedes. On one side is Russia’s Big Diomede – actually part of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug a federal subject of Russia – and just two miles west is Little Diomede which is part of Alaska. Both have small fishing villages, one settled by Russians and the other Americans.

If folks are scared by the geographic proximity of 53 miles, two miles must really freak them out? And they’d best be sitting down for this little tidbit…there is no ratified treaty in place between the United States and Russia that enforces this boundary.1

The last attempts made to negotiate a deal with Russia was in 1991. The person who chaired the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations was none other than Senator Joe Biden from Delaware.

Biden addressed the committee with these words,

“…today the subcommittee meets to consider a measure that constitutes one small step down that path of cooperation. This measure, the U.S.-Soviet Maritime Boundary Treaty, represents the attempt of the two sides to resolve an important dispute through negotiation, compromise, and mutual pledge to abide by the solemn obligations of a bilateral treaty and international law.”2

The dispute this treaty would lay to rest concerns the sovereign rights and jurisdiction of the United States and the Soviet Union in the seas between Alaska and Siberia. The treaty would govern each country’s right to manage fisheries and to conduct oil and gas exploration and development in a vast maritime area.”

In 1990, then Soviet Union leader, Mikhail Gorbachev sought to resolve the ordeal. But the Russian parliament believed he was acting in haste. The Soviet Union was beginning to crumble and they believed Gorbachev was giving away too much fishing, sea passage, and oil and mineral rights to the United States in exchange for other provisions. The USSR collapsed in December of 1991. This left Biden’s sixth month old efforts under the George H. W. Bush administration unanswered. No administration since has attempted to ratify the treaty and I doubt Putin is in the mood for Biden to resume talks.

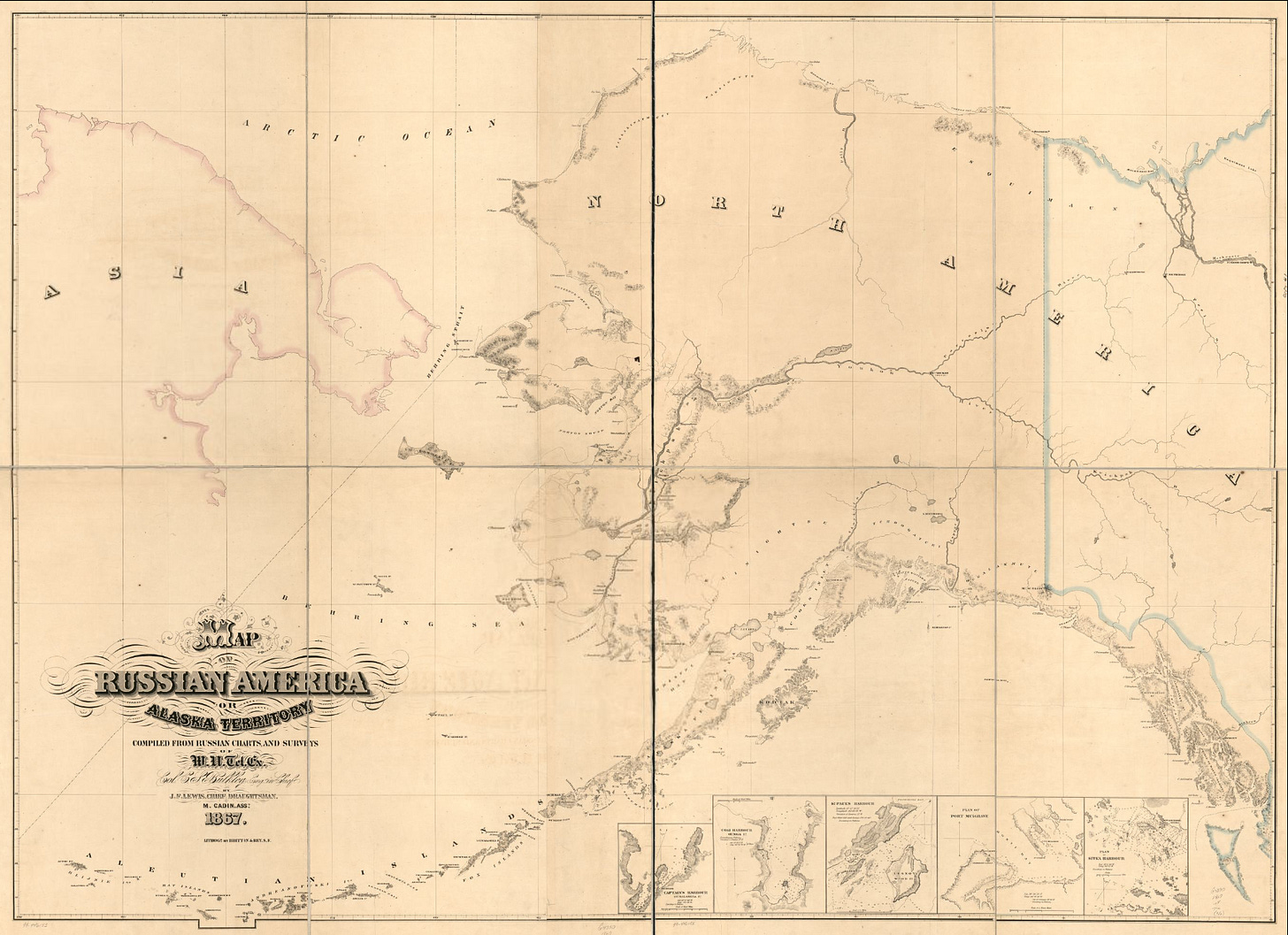

The area maps referred to as Russian America, a piece of land nearly the size of Texas, is what we now call Alaska. It had already been colonized by Siberian fur trappers in the 1700s and the Russian Orthodox Church was already busy trying to convert Indigenous people to Christianity. By 1800 the Russian-American Company was established – organized by Emperor Paul I of Russia. By 1850, 300,000 sea otters were hunted to extinction. Seventeen years later, in 1867, amidst a fur market slump from over hunting, the end of the U.S. Civil War, a Russia battered by the Crimea war ceded Russian America to the United States as part of the Alaska Purchase. It didn’t become a U.S. state until 1959.

Russia sold Alaska to the United States for $7.2 million or $134 million in 2022 dollars. Russia feared they couldn’t defend the territory from the British who were busy trying to colonize Canada and had just defeated the Russians in the Crimea war with the help of the French. So, they expressed interest in selling it to the then U.S. Secretary of State William Seward who had already offered to buy it just a few years prior and was happy to negotiate the purchase.

Biden gave reference to the purchase in his Foreign Relations subcommittee pre-amble by joking,

“the 1867 Convention, by which Russia ceded Alaska to the United States, made it possible for Mr. Murkowski to become a U.S. Senator.”

The Maritime Boundary Agreement this committee aimed resolve, but never did,

“these conflicts by: One, declaring that the 1867 Convention line is the maritime boundary between the United States and the Soviet Union; two, establishing a precise geographic description of the line; and three, providing for the transfer of jurisdiction and Russia rights in four special areas.”

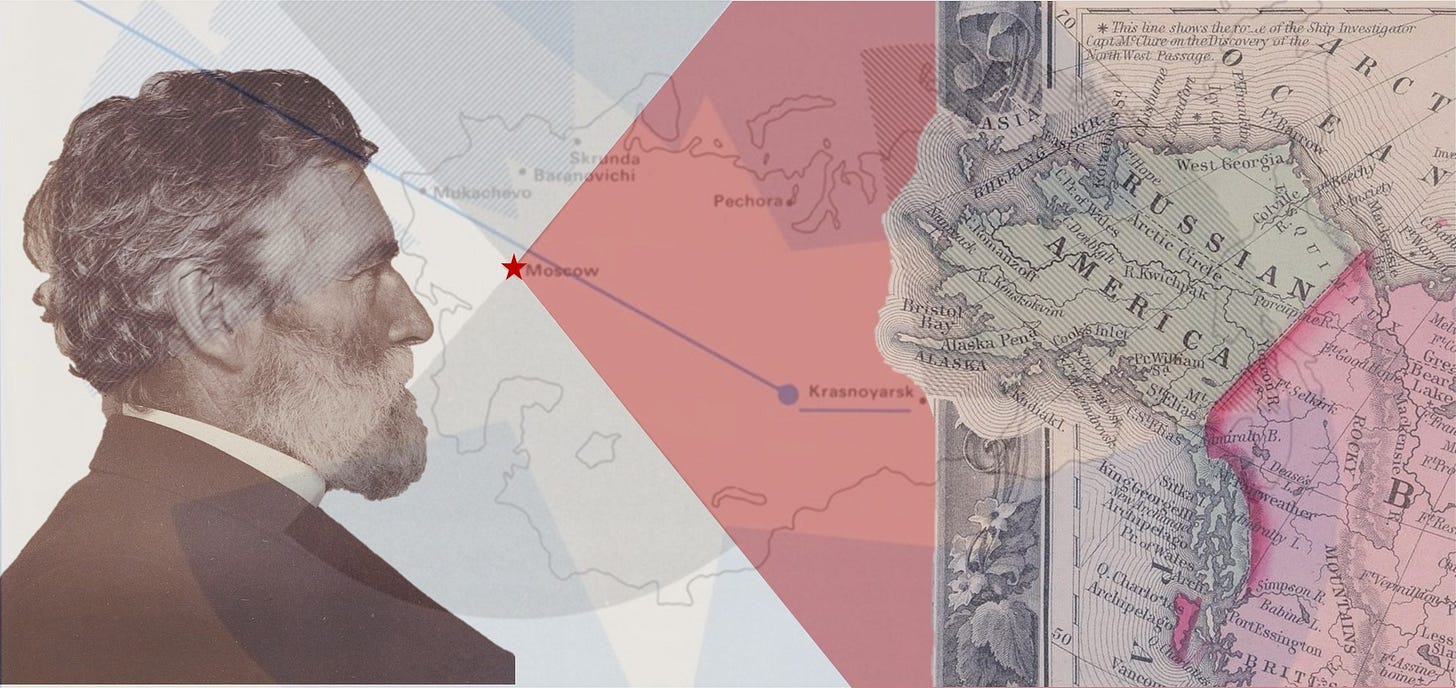

The first American to map the new state of Alaska may take issue with Biden’s use of the words ‘precise geographic description.’ Land wasn’t the only thing the U.S. got for their $7.2 million, they were also handed maps and charts of the region drafted by Russian mapmakers. These were promptly handed over to the man who was soon to become the head of the Pacific branch of the Office of United States Coast Survey, and premiere geographer of the time, George Davidson.

He excelled at geodesy and astronomy coming out of Girard College in 1845. By 1850 he was on the California coast determining accurate latitude and longitude of coastal features. He worked his way up the Pacific coast to Oregon and Washington mapping much of the Puget Sound and naming many of the Olympic Mountains on the Olympic Peninsula. Mt. Ellinor is named after his soon-to-be wife, Ellinor Fauntleroy. The Fauntleroy ferry in Seattle takes you from the Fauntleroy Cove to Vashon Island. Mt. Constance is named after her sister, and the two side-by-side mountains, The Brothers, are named after her two brothers.

His triangulation and astronomical observations were regarded as the highest precision geodesy recorded to that date. The baselines required to accurately triangulate and map the Pacific coast states are named after him – the Davidson Quadrilaterals. And before those Russian maps had been handed over to him, he had already been asked to make maps of the physiography and natural resources of Alaska by the U.S. Congress.

Most maps were copied from Russian maps and others drawn by an Indigenous Chief who knew more about the land than the Russians. A 1937 biography claims “Davidson always got on with Indians—he treated them as men.”3 These maps were included in a report to a congressional committee that resulted in a unanimous vote for America to purchase Russian America from the Russians.

Davidson was mapping Alaska at 51° to 71° latitude north amidst the mosquitos in August of 1867, but less than a year earlier the Office of Coast Survey had sent Davidson down to 5° to 7° latitude north, in January of 1867, to map a potential site for the Panama Canal.

The Office of the Coast Survey was started by Thomas Jefferson in 1807 and still publishes the nautical maps of the U.S. – including the annually published 10 volume publication, United States Coast Pilot. Historically, these guides relied on local mariner knowledge and newspaper articles. They were a practical necessity for private, commercial, and governmental mariners. But in 1858 George Davidson was the first to provide his own accounts making this issue the first official United States Coast Pilot by the Office of the Coast Survey.

Davidson went on to become the president of the California Academy of Sciences, a University of California Regent, and the University of California, Berkley’s first geography professor. He was the department chair from 1898 until 1905.

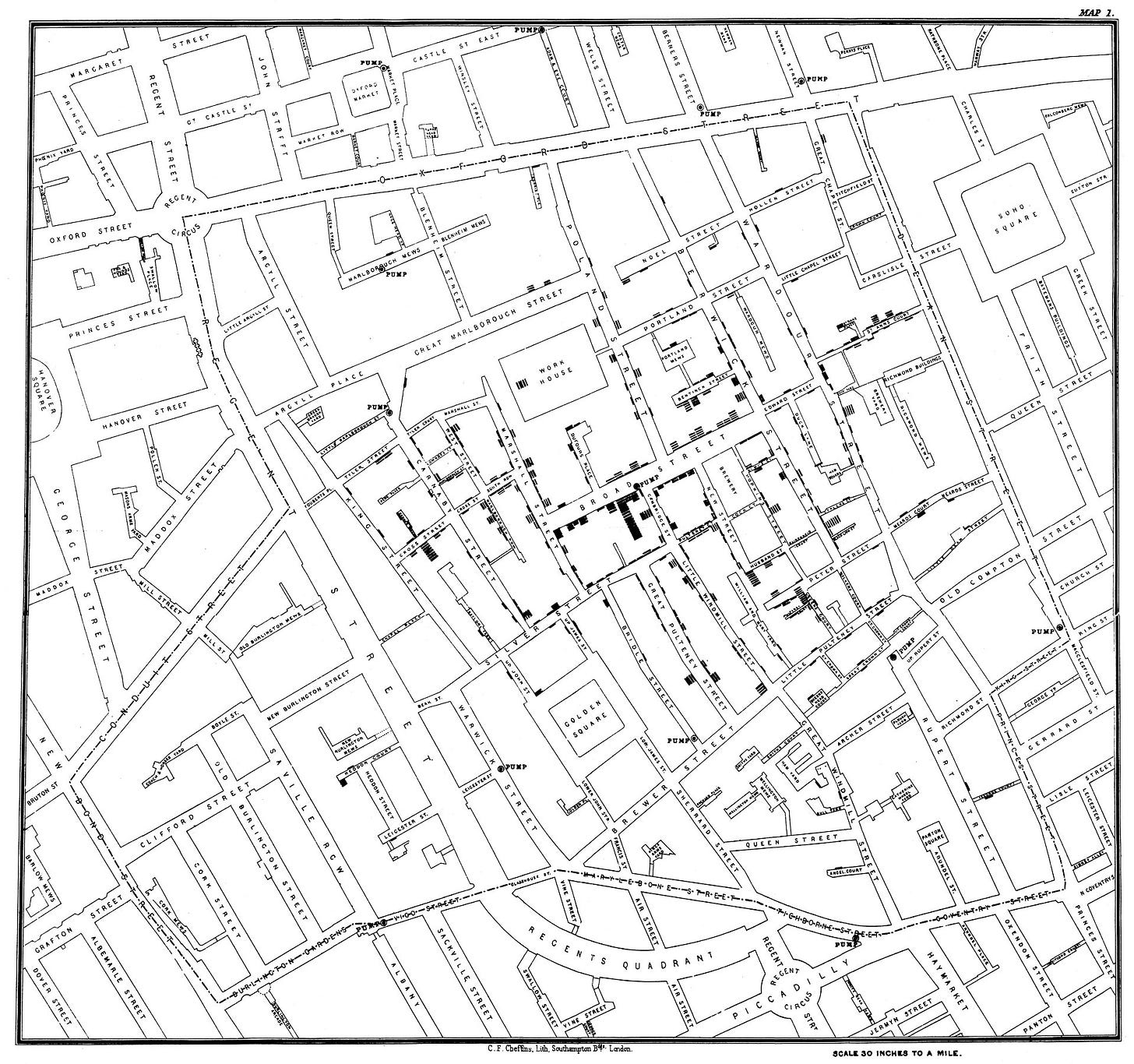

Davidson defined the essence of what map making was at the time. It served the desire and need Jefferson had for precision, utilizing the best surveying and geodesic instruments and techniques of the time. Naturally these were used for exacting territories for colonizing, capitalizing, and exploiting. The United States had become an exuberantly expansionist, empire-building country. But by the middle of the 19th century through the start of the 20th another kind of map was entering its golden age – thematic mapping.

Thematic maps use information not readily observed but are nonetheless part of the geography. For example, maps depicting the weather or statistical information like demographics. They can also include strategic and political information.

The beginning of the 20th century saw the emergence of the United States as a global superpower and the start of the decline of England’s dominance. New territories, like Alaska, were not only getting mapped but were also helping to shift geopolitical dynamics. The world was sufficiently mapped such that world leaders need not send ships afar to determine political strategies.

One of the first and most influential of these geopolitical thematic maps came from England’s equivalent of George Davidson, Sir Halford John Mackinder. In 1904 he wrote a paper that included a map in The Geographic Journal called “The Geographical Pivot of History.” In the introduction here he writes,

“In 400 years the outline of the map of the world has been completed with approximate accuracy…But the opening of the twentieth century is appropriate as the end of a great historic epoch…The missionary, the conqueror, the farmer, the miner, and, of late, the engineer, have followed so closely in the traveller’s footsteps that the world, in its remote borders, has hardly been revealed before we must chronicle its virtually complete political appropriation.”

His map is an oval shaped Mercator projection that puts continental Europe, Africa, and Asia in the middle. Its shape gives it a spherical illusion. The map’s title is The Natural Seats of Power and features three crescent shaped concentric zones. At the center is what he called Pivot Area – which is most of continental Europe, some of Asia and what became the Soviet Union, the next ring is labeled Inner and Marginal Crescent – which is more of Europe, the British Isles and Japan, and furthest from the center are the Lands of Outer or Insular Crescent – which include continental America, most of Africa, and Australia.

Part of Mackinder’s goal was to not only illustrate to an island country — that came to power by sea — just how connected the world is by land. He also simplified the complexities of detailed coastal charts and topographic maps into easy to understand centers of power. Timothy Barney, an Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Communications at the University of Richmond (and self-proclaimed map-nerd) wrote in the Routledge Handbook of Mapping and Cartography that, “Mackinder was prefiguring a social, economic, and political shift in the twentieth century towards a globalized world, all on the flat page of the map.”

Mackinder would not have known it then, but his ‘Pivot Center’ indeed became the focal point of not one, but two world wars that drew powers from all three of the Natural Seats of Power on his map. But he also put thematic geopolitical mapping at the center.

A fight for Ukraine's borders could maul America's own in the Arctic. The Hill. Thomas Emanuel Dans. 2022.

U.S. Soviet Maritime Boundary Agreement, Treaty Doc. 101-22 ..., Volume 4. United States Congress. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. 1991.

Biographical Memoir of George Davidson 1825-1911. National Academy of Sciences. Charles B. Davenport. 1937.