Hello Interactors,

From election lies to climate denial, misinformation isn’t just about deception — it’s about making truth feel unknowable. Fact-checking can’t keep up, and trust in institutions is fading. If reality is up for debate, where does that leave us?

I wanted to explore this idea of “post-truth” and ways to move beyond it — not by enforcing truth from the top down, but by engaging in inquiry and open dialogue. I examine how truth doesn’t have to be imposed but continually rediscovered — shaped through questioning, testing, and refining what we know. If nothing feels certain, how do we rebuild trust in the process of knowing something is true?

THE SLOW SLIDE OF FACTUAL FOUNDATIONS

The term "post-truth" was first popularized in the 1990s but took off in 2016. That’s when Oxford Dictionaries named it their Word of the Year. Defined as “circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”, the term reflects a shift in how truth functions in public discourse.

Though the concept of truth manipulation is not new, post-truth represents a systemic weakening of shared standards for knowledge-making. Sadly, truth in the eyes of most of the public is no longer determined by factual verification but by ideological alignment and emotional resonance.

The erosion of truth infrastructure — once upheld by journalism, education, and government — has destabilized knowledge credibility.1 Mid-20th-century institutions like The New York Times and the National Science Foundation ensured rigorous verification.23 But with rising political polarization, digital misinformation, and distrust in authority, these institutions have lost their stabilizing role, leaving truth increasingly contested rather than collectively affirmed.

The mid-20th century exposed truth’s fragility as propaganda reshaped public perception. Nazi ideology co-opted esoteric myths like the Vril Society, a fictitious occult group inspired by the 1871 novel The Coming Race, which depicted a subterranean master race wielding a powerful life force called "Vril."

This myth fed into Nazi racial ideology and SS occult research, prioritizing myth over fact.4 Later, as German aviation advanced, the Vril myth evolved into UFO conspiracies, claiming secret Nazi technologies stemmed from extraterrestrial contact and Vril energy, fueling rumors of hidden Antarctic bases and breakaway civilizations.

Distorted truths have long justified extreme political action, demonstrating how knowledge control sustains authoritarianism. Theodor Adorno and Hannah Arendt, Jewish-German intellectuals who fled the Nazis, later warned that even democracies are vulnerable to propaganda. Adorno5 (1951) analyzed how mass media manufactures consent, while Arendt6 (1972) showed how totalitarian regimes rewrite reality to maintain control.

Postwar skepticism, civil rights movements, and decolonization fueled academic critiques of traditional, biased historical narratives.78 By the late 20th century, universities embraced theories questioning the stability of truth, labeled postmodernist, critical, and constructivist.9

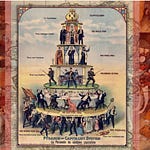

Once considered a pillar of civilization10, truth was reframed by French postmodernist philosophers Michel Foucault and Jean Baudrillard as a construct of power. Foucault argued institutions define truth to reinforce authority, while Baudrillard claimed modern society had replaced reality with media-driven illusions.1112 While these ideas exposed existing power dynamics in academic institutions, they also fueled skepticism about objective truth — paving the way for today’s post-truth crisis.

Australian philosophy professor, Catherine (Cathy) Legg highlights how intellectual and cultural shifts led universities to question their neutrality, reinforcing postmodern critiques that foreground subjectivity, discourse, and power in shaping truth. Over time, this skepticism extended beyond academia, challenging whether any authority could claim objectivity without reinforcing existing power structures.

These efforts to deconstruct dominant narratives unintentionally legitimized radical relativism — the idea that all truths hold equal weight, regardless of evidence or logic.13 This opened the door for "alternative facts", now weaponized by propaganda. What began as a challenge to authoritarian knowledge structures within academia escaped its origins, eroding shared standards of truth. In the post-truth era, misinformation, ideological mythmaking, and conspiracy theories thrive by rejecting objective verification altogether.

Historian Naomi Oreskes describes "merchants of doubt" as corporate and political actors who manufacture uncertainty to obstruct policy and sustain truth relativism.14 By falsely equating expertise with opinion, they create the illusion of debate, delaying action on climate change, public health, and social inequities while eroding trust in science. In this landscape, any opinion can masquerade as fact, undermining those who dedicate their lives to truth-seeking.

PIXELS AND MYTHOLOGY SHAPE THE GEOGRAPHY

The erosion of truth infrastructures has accelerated with digital media, which both globalizes misinformation and reinforces localized silos of belief.15 This was evident during COVID-19, where false claims — such as vaccine microchips — spread widely but took deeper root in communities with preexisting distrust in institutions. While research confirms that misinformation spreads faster than facts, it’s still unclear if algorithmic amplification or deeper socio-political distrust are root causes.16

This ideological shift is strongest in Eastern Europe and parts of the U.S., where institutional distrust and digital subcultures fuel esoteric nationalism.17 Post-Soviet propaganda, economic instability, and geopolitical tensions have revived alternative knowledge systems in Russia, Poland, and the Balkans, from Slavic paganism to the return of the Vril myth, now fused with the Save Europe movement — a digital blend of racial mysticism, ethnic nostalgia, and reactionary politics.

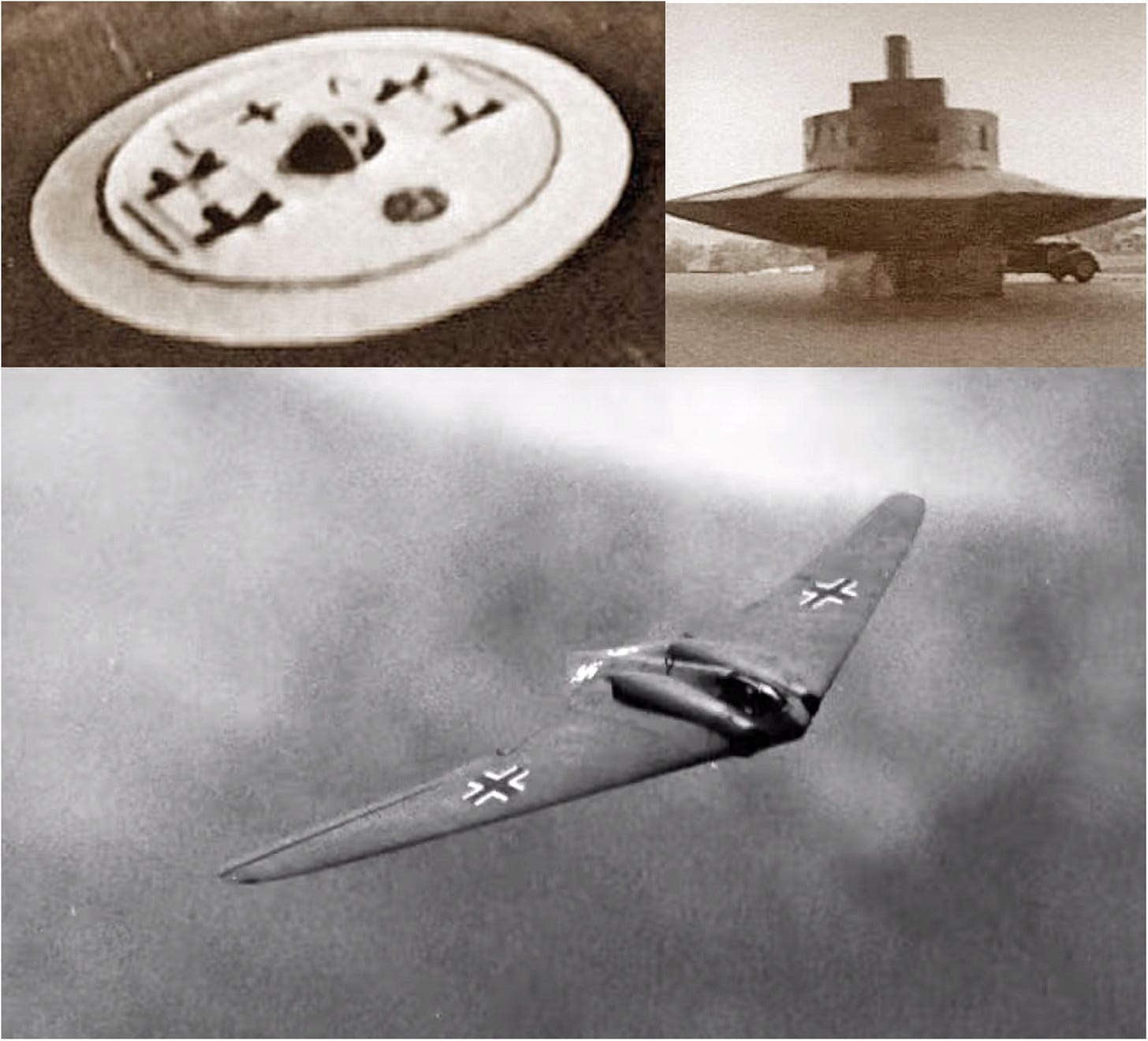

Above ☝️is a compilation of TikTok videos currently being pushed to my 21 year old son. They fuse ordinary, common, and recognizable pop culture imagery with Vril imagery (like UFO’s and stealth bombers) and esoteric racist nationalism, religious fundamentalism, and hyper-masculine mythologies.

A similar trend appears in post-industrial and rural America, where economic decline, government distrust, and cultural divides sustain conspiratorial thinking, religious fundamentalism, and hyper-masculine mythologies. The alt-right manosphere mirrors Eastern Europe’s Vril revival, with figures like Zyzz and Bronze Age Pervert offering visions of lost strength. Both Vril and Save Europe frame empowerment as a return to ethnic or esoteric power (Vril) or militant resistance to diversity (Save Europe), turning myth into a tool of political radicalization.

Climate change denial follows these localized patterns, where scientific consensus clashes with economic and cultural narratives. While misinformation spreads globally, belief adoption varies, shaped by economic hardship, institutional trust, and political identity.

In coal regions like Appalachia and Poland, skepticism stems from economic survival, with climate policies seen as elitist attacks on jobs. In rural Australia, extreme weather fuels conspiracies about government overreach rather than shifting attitudes toward climate action. Meanwhile, in coastal Louisiana and the Netherlands, where climate impacts are immediate and undeniable, denial is rarer, though myths persist, often deflecting blame from human causes.

Just as Vril revivalism, Save Europe, and the MAGA manosphere thrive on post-industrial uncertainty, climate misinformation can also flourish in economically vulnerable regions. Digital platforms fuel a worldview skewed, where scrolling myths and beliefs are spatially glued — a twisted take on 'think globally, act locally,' where fantasy folklore becomes fervent ideology.

FINDING TRUTH WITH FRACTURED FACTS…AND FRIENDS

The post-truth era has reshaped how we think about knowledge. The challenge isn’t just misinformation but growing distrust in expertise, institutions, and shared reality. In classrooms and research, traditional ways of proving truth often fail when personal belief outweighs evidence. Scholars and educators now seek new ways to communicate knowledge, moving beyond rigid certainty or radical relativism.

Professor Legg has turned to the work of 19th-century American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, whose ideas about truth feel surprisingly relevant today. Peirce didn’t see truth as something fixed or final but as a process — something we work toward through questioning, testing, and refining our understanding over time.

His approach, known as pragmatism, emphasizes collaborative inquiry, self-correction, and fallibilism — the idea that no belief is ever beyond revision. In a time when facts are constantly challenged, Peirce’s philosophy offers not just a theory of truth, but a process for rebuilding trust in knowledge itself.

For those unfamiliar with Peirce and American pragmatism, a process that requires collaborating with truth deniers may seem not only unfun, but counterproductive. But research on deradicalization strategies suggests that confrontational debunking (a failed strategy Democrats continue to adhere to) often backfires. Lecturing skeptics only reinforces belief entrenchment.

In the early 1700’s Britain was embroiled in the War of Spanish Succession. Political factions spread blatant falsehoods through partisan newspapers. It prompted Jonathan Swift, the author of Gulliver’s Travels, to observe in The Art of Political Lying (1710) that

"Reasoning will never make a man correct an ill opinion, which by reasoning he never acquired."18

This is likely where we get the more familiar saying: you can't argue someone out of a belief they didn't reason themselves into. Swift’s critique of propaganda and public gullibility foreshadowed modern research on cognitive bias. People rarely abandon deeply held beliefs when confronted with facts.

Traditionally, truth is seen as either objectively discoverable (classical empiricism) — like physics — or constructed by discourse and power (postmodernism) — like the Lost Cause myth, which recast the Confederacy as noble rather than pro-slavery. It should be noted that traditional truth also comes about by paying for it. Scientific funding from private sources often dictates which research is legitimized. As Legg observes,

“Ironically, such epistemic assurance perhaps rendered educated folk in the modern era overly gullible to the written word as authority, and the resulting ‘fetishisation’ of texts in the education sector has arguably led to some of our current problems.”19

Peirce, however, offered a different path:

truth is not a fixed thing, but an eventual process of consensus reached by a community of inquirers.

It turns out open-ended dialogue that challenges inconsistencies within a belief system is shown to be a more effective strategy.20

This process requires time, scrutiny, and open dialogue. None of which are very popular these days! It should be no surprise that in today’s fractured knowledge-making landscape of passive acceptance of authority or unchecked personal belief, ideological silos reinforce institutional dogma or blatant misinformation. But Peirce’s ‘community of inquiry’ model suggests that truth can’t be lectured or bought but strengthened through collective reasoning and self-correction.

Legg embraces this model because it directly addresses why knowledge crises emerge and how they can be countered. The digital age has resulted in a world where beliefs are reinforced within isolated networks rather than tested against broader inquiry. Trump or Musk can tweet fake news and it spreads to millions around the world instantaneously.

During Trump’s 2016 campaign, false claims that Pope Francis endorsed him spread faster than legitimate news. Misinformation, revisionist history, and esoteric nationalism thrive in these unchecked spaces.

Legg’s approach to critical thinking education follows Peirce’s philosophy of inquiry. She helps students see knowledge not as fixed truths but as a network of interwoven, evolving understandings — what Peirce called an epistemic cable made up of many small but interconnected fibers. Rather than viewing the flood of online information as overwhelming or deceptive, she encourages students to see it as a resource to be navigated with the right tools and the right intent.

To make this practical, she introduces fact-checking strategies used by professionals, teaching students to ask three key questions when evaluating an online source:

Who is behind this information? (Identifying the author’s credibility and possible biases)

What is the evidence for their claims? (Assessing whether their argument is supported by verifiable facts)

What do other sources say about these claims? (Cross-referencing to see if the information holds up in a broader context)

By practicing these habits, students learn to engage critically with digital content. It strengthens their ability to distinguish reliable knowledge from misinformation rather than simply memorizing facts. It also meets them where they are without judgement of whatever beliefs they may hold at the time of inquiry.

If post-truth misinformation reflects a shift in how we construct knowledge, can we ever return to a shared trust in truth — or even a shared reality? As institutional trust erodes, fueled by academic relativism, digital misinformation, and ideological silos, myths like climate denial and Vril revivalism take hold where skepticism runs deep. Digital platforms don’t just spread misinformation; they shape belief systems, reinforcing global echo chambers.

But is truth lost, or just contested? Peirce saw truth as a process, built through inquiry and self-correction. Legg extends this, arguing that fact-checking alone won’t solve post-truth; instead, we need a culture of questioning — where people test their own beliefs rather than being told what’s right or wrong.

I won’t pretend to have the answer. You can tell by my bibliography that I’m a fan of classical empiricism. But I’m also a pragmatic interactionist who believes knowledge is refined through collaborative inquiry. I believe, as Legg does, that to move beyond post-truth isn’t about the impossible mission of defeating misinformation — it’s about making truth-seeking more compelling than belief. Maybe even fun.

What do you think?

Legg, C. (2024). Getting to Post-Post-Truth. Journal of Philosophy in Schools, 11(1).

Schudson, M. (2001). The Sociology of News. W. W. Norton & Company.

Guston, D. H. (2000). Between Politics and Science: Assuring the Integrity and Productivity of Research. Cambridge University Press.

Goodrick-Clarke, N. (2002). Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity.

Adorno, T. W. (1951). The Authoritarian Personality. Harper & Row.

Arendt, H. (1972). Crises of the Republic: Lying in Politics. Harcourt Brace.

Schwarz, Bill. (2005). Conquerors of Truth: Reflections on Postcolonial Theory. In The Expansion of England (pp. 27-52). Taylor & Francis.

Peters, Michael, & Lankshear, Colin. (2013). Postmodern Counternarratives. In Counternarratives: Cultural Studies and Critical Pedagogies in Postmodern Spaces. Taylor & Francis.

(1)

(1)

Foucault, Michel. (1975). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Pantheon Books.

Baudrillard, Jean. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Fuller, S. (2018). Post-Truth: Knowledge as a Power Game. Anthem Press.

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2010). Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. Bloomsbury Press.

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The Spread of True and False News Online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the “Post-Truth” Era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353-369.

White, E. D. (2024). The New Witches of the West: Tradition, Liberation, and Power. Cambridge University Press

Swift, Jonathan. (1710). The Art of Political Lying. London: John Morphew.

(1)

(16)