Hello Interactors,

This post is part two of a three week experiment. I’ve divided my topic into three parts each taking a bit less time for you to read or listen to. They each can stand on their own, but hopefully come together to form a bigger picture. Please let me know what you think.

Maps are such a big part of our daily lives that it’s easy to let them wash over us. But they’re also very powerful forms of communication that require our attention and scrutiny. If we don’t, we run the risk of being hypnotized and even deluded.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

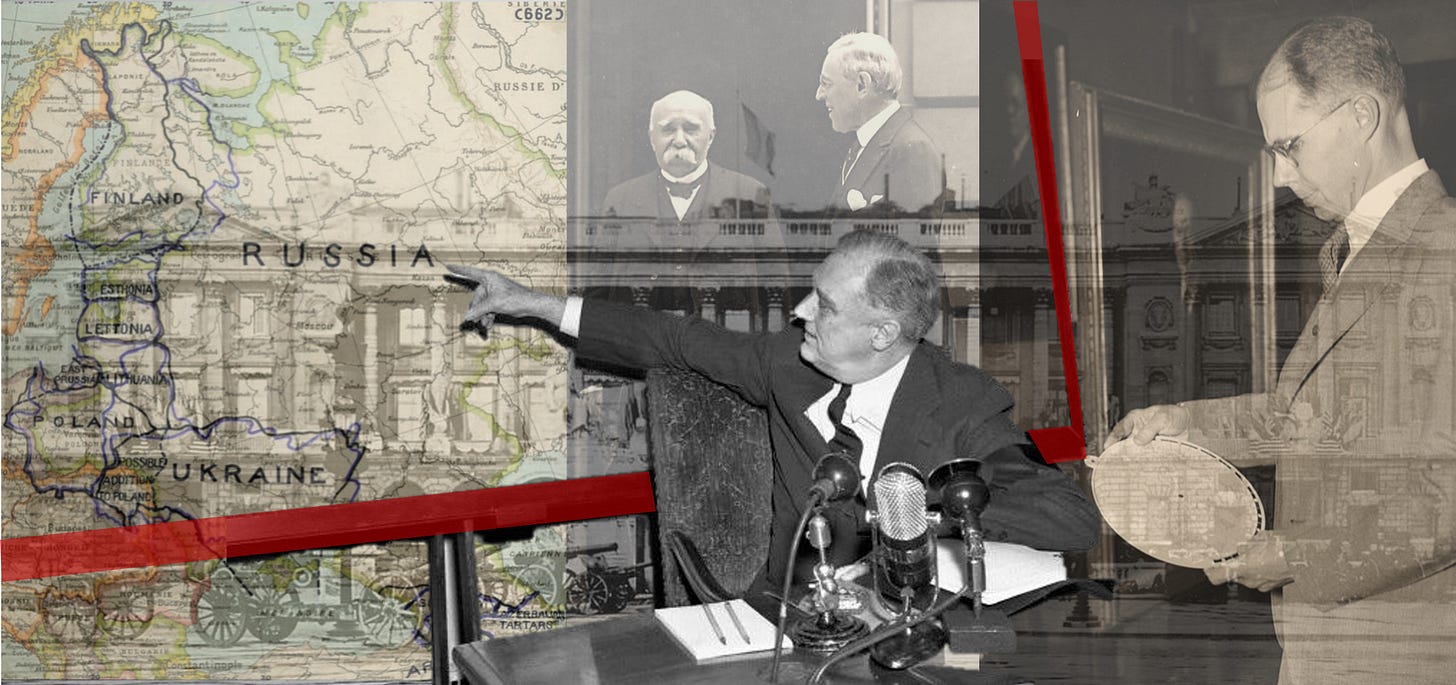

Both World Wars exemplified the hauntingly prescient title of that 1904 paper by England’s eminent geographer and burgeoning politician, Sir Malford MacKinder – The Geographical Pivot of History. And his most famous simplified world map depicting the Natural Seats of Power inspired derivatives all around the world. That was especially true at the conclusion of World War I and the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.

Peace preparations by the United States began the same month they declared War on Germany in April of 1917. By November a team of researchers, writers, lawyers, and cartographers moved from the New York City Public Library to the third floor of the American Geographical Society. Surrounded by a collection of maps and books the team set work on what was called the Inquiry.

One of the primary geographers assigned to this effort was Mark Sylvester William Jefferson. He was a professor at the Michigan State Normal School at Ypsilanti and specialized in the thematic mapping of population distribution. He even invented a term for it – anthropography. The distinguished professor emeritus of geography at Southern Connecticut State University, Geoffrey L. Martin says,

“His maps were accurate, attractive, and invariably ingenious in design.”1

These maps for the Paris conference were to convey reams of physiographic and demographic information regarding Europe and surrounding regions. Martin notes,

“Jefferson had the remarkable ability to simplify complexity, to inspire ingenuity of cartographic expression, and to display such manual dexterity with economy of line that his leadership, long hours, and indefatigable fascination with the enterprise insured success for the mapping effort.”

Jefferson, and his team of cartographers, joined a select group, including President Woodrow Wilson, on board the USS George Washington headed to France in December of 1918. By the middle of December the Inquiry team assembled in a hotel in Paris, including Jefferson and his twenty-five draftsmen. The team grew in size requiring them to knock down a wall at the Hôtel de Crillon, one of Paris’ finest hotels on the Champs-Élysées.2

Martin, pulling from Jefferson’s diary writes,

“By February of 1919 Jefferson’s team of cartographers spanned five rooms, an engraving apparatus was provided, and armed guards were posted at the door.”

During the proceedings, Jefferson sat on the geographers’ commission. Other geographers and attendees were impressed and overwhelmed by the cartographic prowess of the American delegation. Chatter in the halls, parks, and hotels centered on the role maps played during the convention. They were not only the common denominator amongst a diverse delegation, but also the premiere communicator and persuader.

Martin concludes,

“The value of maps had been recognized prior to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, yet at Paris the map suddenly became everything.”

The momentum from this event followed those involved in the Inquiry back the United States. The State Department experienced firsthand the influential power of cartography and established their own geographic division and the Office of Geographer. The division’s maps and collections started with those made during the Paris Peace Conference. They were organized by Colonel Lawrence Martin who served under Woodrow Wilson and became the first head of the department in 1921.

Martin retired in 1924 and selected Samuel Whittemore Boggs to replace him. Boggs came to New York in 1914 and worked compiling and editing maps. In 1921 he began a Master’s program at Columbia studying under two professors who were also cartographers at the Paris Peace Conference. These men, like many of those involved in preparing for the conference, left idealistic that maps could lead to a fair and just conclusion of international territorial disputes.

Boggs embodied that spirit coming out of college and combined it with imaginative approaches and highly academic, technical cartography skills. It made him well positioned for the role political geography and cartography was about to play as territorial pieces continued to shift around the earth’s spherical chess board.

That proverbial board was also shrinking as the airplane became an increasingly important element of war and travel. The Library of Congress map librarian and geographer, Walter Ristow, called this ‘air age geography.’ The war, and the proliferation of maps, inspired interest from the public in world geography.

In 1942, three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt took to the radio in a Fireside Chat he called “On the Progress of War”. Pearl Harbor was a vivid reminder to the American public that air-age globalism had clearly arrived. He said,

“This war is a new kind of war. It is different from all other wars of the past, not only in its methods and weapons but also in its geography. It is warfare in terms of every continent, every island, every sea, every air-lane in the world.”

But then he did something I suspect no other president had done prior or since and asked the American public to pull out their own world map and following along with him. It’s an indication of just how pervasive and commercialized mapmaking had become. He continued,

“That is the reason why I have asked you to take out and spread before you (the) a map of the whole earth, and to follow with me in the references which I shall make to the world-encircling battle lines of this war."

Maps as a tool of communicating geopolitics had hit the mainstream. By the 1940’s Boggs had recognized that maps he and others were producing could do one of two things: either ‘delude the public’ or ‘inform them.’ Being the idealist he was, he worried most about the risks of delusion.

He wrote an article in 1947 in The Scientific Monthly titled, Cartohypnosis. Referring to maps he used in territorial disputes in the deserts of Afghanistan he says,

“Map-conscious people, however, usually accept subconsciously and uncritically the ideas that are suggested to them by maps. In part because maps appear to represent facts pertaining to mother earth herself, veracity and authority are frequently attributed to them beyond their deserts.”

He continued,

“In what might be called ‘cartohypnosis’ or ‘hypnotism by cartography,’ the map user or the audience exhibits a high degree of suggestibility in respect to stimuli aroused by the map and its explanatory text.”

In what could be seen as now as a critical indictment of the U.S. government by an employee of the U.S. State Department he says,

“And frequently a sort of mass hypnotism is practiced by men who attempt to delude the public.”

All the while, he seemed to remain idealistic reminding us that,

“Sometimes self-hypnotism and illusion occur quite innocently…[and] may also be used effectively to dehypnotize people…we should therefore consider what maps may be made, and how they may be used to awaken people to an intelligent understanding of the world and the problems of our times.”

The History of Cartography. Volume Six: cartography in the twentieth century. “Paris Peace Conference”. Geoffrey L. Martin. 2015.

Ibid.