Hello Interactors,

We all intuitively feel the world is falling into selfishness, defensiveness, and pettishness. Me, my, and eye for an eye. If the words we see in the books we read are any indication, it’s not just intuition but fact. And the shift started right around 1980.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

WE PRAY FOR NOT FOR US, BUT ME

Do you use words like believe, hope, fear, sense, feel, pray, soul, or mystery? Or are you more likely to use words like science, technology, model, method, fact, data, analysis, transmission, or system? If you’ve read even one Interplace essay, then I believe that my preference is no mystery! And I hope and pray you’ll read more than one. After all, I search for facts and data and then perform some analysis of the science of systems.

What if I asked whether you use the words I and me more than we and us? One look at social media and it would be apparent. All the social strife, climate fright, or COVID concern has many people screaming into the digital void or retreating to the nearest corner curled up mumbling to themselves and their rectangular shiny black mirror of a screen. This is a very personal and individual reaction that commonly begins with the word “I” followed by “hope” or “pray.”

What if I told you the world has both been increasingly using feeling words, like sense and soul and individual words, like I and me since 1980? What’s more intriguing is these two uses are correlated. The band R.E.M. was sending us clues back in 1987 when they released their song, “It’s the end of the world as we know it – [and I feel fine]. In it they sing,

“Save yourself, serve yourself

World serves its own needs, listen to your heart bleed”

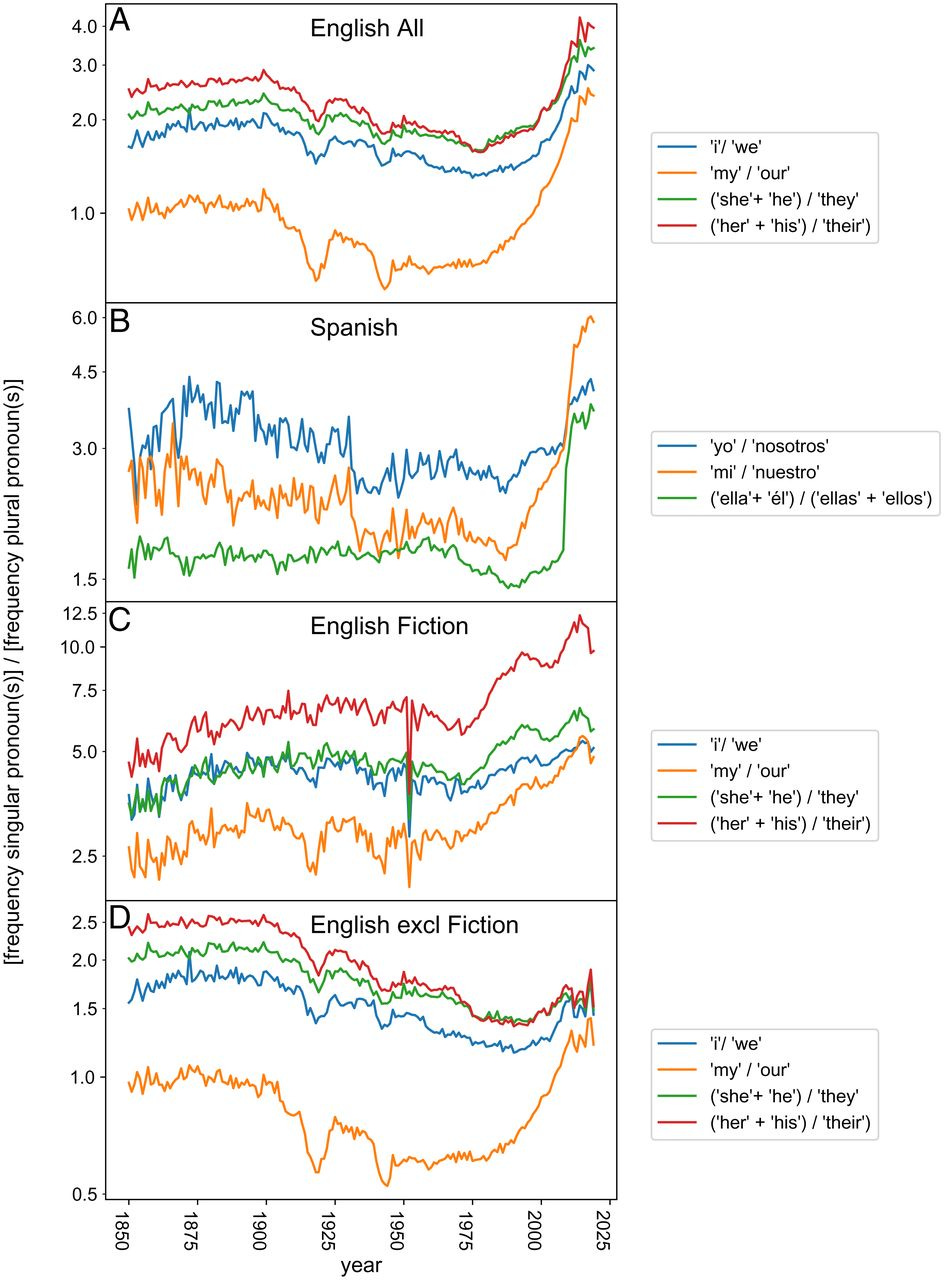

A paper came out just last month that provides evidence of this dialectical drift. The researchers, led by Martin Sheffer, of Wageningen University in The Netherlands, assembled a massive corpus of text from millions of books found on Google Books dating from 1850 to 2019. Reading and analyzing the text of this many books is humanly impossible, so they put machines to work. They used text analysis tools to search, count, find correlations, and detect sentiment.

A simple example of this can be done by anybody with access to the internet. There are websites that will count the occurrences of a given word in a body of text and then arrange them into a word ‘cloud’. The largest word in the cloud represents the most frequently used word and the smallest the most infrequent. Here's a word cloud of the over 130,000 words I wrote on Interplace in 2021.

But these simple clouds don’t say anything about what kind of words they are or what associations they may have with other words or ideas. And they don’t lend insight into what words are likely to occur together. But there are statistical methods and software tools that, if given enough clean data, can cluster words of similar meaning and correlate them to the occurrence of other words.

What these researchers discovered is that “words associated with rationality, such as “determine” and “conclusion,” rose systematically after 1850, while words related to human experience such as “feel” and “believe” declined.” Words to do with senses, spirituality, emotions, and personal relationships are “sentiment” laden words that reflect a “personal world view.” Over time, they were displaced by “fact based” words used in argumentation of “societal systems”. They also found this pattern correlates with the rise of we and us and the decline of I and me after 1850.1

And then, starting around 1980, this trend peaked and then flip-flopped and the trend accelerated in 2007. That is when, the authors write,

“across languages, the frequency of fact-related words dropped while emotion-laden language surged, a trend paralleled by a shift from collectivistic to individualistic language.”2

Of course, explaining why this happened is much harder than finding the evidence, which is also no small feat. The researchers speculate that 1850 was a time when the Industrial Revolution was hitting its stride. Science and technology were credited with economic prosperity and the promise of logic and rationalistic determinism seeped into culture and then books. Out with the mystical and in with the technical. It’s what the sociologist Max Weber called a process of “disenchantment”.

But sociologist and political theorist, Steven Lukes, researched and wrote a book on the origins of “individualism.” He reveals the word ‘individualism’ has multiple ‘semantic histories’ and meanings. It entered the scene in the nineteenth century along with two other big ‘isms’ – ‘socialism’ and ‘communism.’

The first use came in 1820 in France in response to the French Revolution. Because conservative elites, especially religious leaders, viewed the revolt against the establishment as a result of Enlightenment thinkers and doers, individualism was a derogatory term. Lukes writes,

“Conservative thought in the early nineteenth century was virtually unanimous in condemning the appeal to the reason, interests and rights of the individual.”3

Put simply, it was seen as the beginnings of anarchy. According to French dictionaries, it remains a pejorative word in France to this day. There were reasons for suppressing individualistic thoughts, principles, and beliefs and they had everything to do with maintaining political, social, and religious order.

Meanwhile, for the socialists of the 1800s, the term ‘individualism’ offered a counter to their ideal ‘collectivism.’ They believed that individuals who drift from the herd become prey to exploitive laissez-faire industrial capitalism. Lukes points to the French philosopher and economist, Pierre Leroux, who argued individualism would lead to

“’everyone for himself, and…all for riches, nothing for the poor’, which atomized society and made men into ‘rapacious wolves’…”4

Individualism as a counterweight to collectivism is also what the British latched onto well into the late nineteenth century. So both the political, religious, and philosophical left and right had their own reasons for squelching individualism and their associative words in the nineteenth century.

THE BELOVED RUGGED HUG

After the French aristocrat and politician, Alexis de Tocqueville, extensively toured America in 1831 he concluded democracy, of which he was dubious, is rooted in individualism. Lukes writes that Tocqueville warned that individualism led to

“the apathetic withdrawal of individuals from public life into a private sphere and their isolation from one another, with a consequent weakening of social bonds. Such a development, Tocqueville thought, offered dangerous scope for the unchecked growth of the political power of the state.”5

As we sit her nearly 200 years later amidst rising authoritarian threats, he may have a point.

As the nineteenth century came to a close collectivist social and political structures were weakening. This is what Lukes claims gave rise to the beginnings of a turn toward individualism. He writes, “For the last quarter of the century was the period in which the market-driven politics of neoliberalism swept across the globe.” He notes that it was the “crisis of the welfare state and the spectacular fall of communism” that led to a “depletion of the meaning of ‘socialism.’” He says the term could no longer be “used with the same confidence” especially “in contrast to its two traditional antonyms, ‘capitalism’ and ‘individualism.’”

And then, in 1922, then U.S. Commerce Secretary, Herbert Hoover, published a small but influential book called “American Individualism.” He then campaigned on the idea of ‘rugged individualism’ and the romantic, though overstated, idea of the self-reliant American frontiersman. Having spent time in Europe at the end of WWI witnessing its devastation he returned to write in his book that there were “’two convictions … dominant in [his] mind.’

The first was that “the ideology of socialism, as tested before his eyes in Europe, was a catastrophic failure.” “Socialism”, he wrote, went against “the fundamental human impulse of self-interest” and “was unable to motivate men and women to produce sufficient goods for the needs of society.”6

The second conviction was that America, “The New World” as he called it, was far removed from European “imperialism, fanatic ideologies, ‘age-old hates,’ racial antipathies, dictatorships, power politics, and class stratifications.” And to be fair, Hoover’s book portrays a fairly progressive stance on individualism. He believed there is a limit to individualism and warned that

“We shall never remedy justifiable discontent until we eradicate the misery which the ruthlessness of individualism has imposed upon a minority.”7

Of course, his actions spoke otherwise as he blamed the depression he failed to remedy as President on low wage minority Mexican immigrants southern farmers relied on to keep costs down. He deported one million Mexican Americans after enacting a program he called “American jobs for real Americans.” Sound familiar? I guess individualism matters only if you’re white. And perhaps, ruthless.

Many different philosophers, politicians, and practitioners have nuanced variations and interpretations of the word ‘individualism’ over the last 200 years, but Lukes found that only these three have survived. The far right believes individualism leads to anarchy, the far left believes individualism is a symptom of selfishness, and hardcore capitalists believe individualism breeds progress and prosperity for all.

Which makes it all the more difficult to pin down what happened around 1980 that marked a shift from collectivistic ‘we’ to the more individualistic ‘me’? The authors of the study offer a clue: The Information Age. The 1980s was when the information age was just getting rolling. In 1980 Microsoft had been around for five years already. The Apple II, the first mass-marketed personal computer, had been selling for three years. And a new internet consortium was formed called the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). They quickly invented and adopted three very familiar suffixes: .com, .gov, and .edu. By 1985 Prodigy, Compuserve, and Quantum Computer Services – later named America Online (AOL) – were connecting people with access to a computer to the internet.

People with such means started expressing themselves to people around the world using words and pictures over the internet. By the time 2007 rolled around the iPhone had come out and with it the ability to tap, type, and shoot from a pocket-sized super computer/phone. We may fret over the time spent on screens passively consuming massive amounts of information, but we forget not all of it is passive. If you consider all the thumbs and fingers typing into chat boxes, messaging apps, and comment streams, or posting and broadcasting pictures and videos on social media platforms, there are more people writing and publishing than ever in the history of humanity. It’s bound to have an effect on the language we use.

The 1980s also marked the beginning of what has become out-sized income inequality in America. While Jimmy Carter had spent four years making peace in the world, trying to get us on solar power, and adopt the metric system, he struggled to make progress on inflation. Meanwhile, neoliberals from both parties had grown tired of attempts of social reform since the 60s and 70s. Just as in the 1800s, neoliberals became disenchanted with the passivist and collectivist attempts at another FDR style Great Society that wreaked of socialism.

Instead, they stood on principles of American exceptionalism, classical liberalism, traditional family values, free markets, free trade, Judeo-Christian values, limited government, moral absolutism, natural law, rule of law, protectionism, Republicanism, and tradition. It was the celebration of the individual, singular beliefs, and individual gain – I/me – over the promise of a diverse collective; a systematic community of reciprocity – we/us.

WISELY AND SLOW; THEY STUMBLE THAT RUN FAST. — SHAKESPEARE

What held constant through a string of both Democrat and Republican presidents are neoconservative economic policies that have left the United States with the most extreme wealth disparity in its history. For those who have benefitted the most, it may be easy for them to point to individualism as the reason for their success. This fits with Hoover’s idea of the rugged individualist who ‘earned’ their way to the top through no means but their own effort. Like Frank Sinatra’s song, “I did it my way.” It’s just as Leroux warned in the 1800s, ’everyone for himself, and…all for riches, nothing for the poor.’

For those who have seen their relative income decline since 1980, it may be easy for them to feel, as the socialists of the 1800s worried, that they were exploited by capitalism and corporate America. Perhaps they may feel, as Tocqueville warned, an apathetic withdrawal from public life from unchecked growth of a political power that has seemingly turned their back on them over the last 40 years.

The economists at Oxford’s Our World in Data show that from 1980 to 2014, “independently of where you are in the US income distribution, those who are richer have seen larger income growth.” But they go on to point out that this hasn’t always been the case. In 1980, “independently of where you were in the income distribution, those who were poorer used to enjoy larger income growth.”

Trump preyed on the beliefs and emotions that surround this science and these facts and it got him elected.

Meanwhile, other fears and anxieties have led many more to retreat to hyperbolic emotion and self-righteousness. A pandemic hit stoking fear and uncertainty. Climate change has caused extreme variability in weather patterns heightening existential anxiety in many. The list goes on and on.

Consequently, we all have reasons to be afraid of something and it can influence the words we use. The authors of the paper lean on what some scientists believe are two different cognitive modes of operation: System 1 (fast) and System 2 (slow). System 1 is intuitive, effortless, and without control. System 2 is deliberate, effortful, and rational. The researchers plotted System 1 words that relate to “belief, spirituality, sapience, intuition, and senses” and System 2 words that are rooted in “science, technology, and quantification”. They show the frequency of System 1 words decreased after 1850 and then increased after 1980 while System 2 words increased after 1850 and then declined after 1980. They plotted words found in American English, British English, German, French, Italian, and Russian and similar patterns emerged.

Could it be the more connected we become and the faster we consume and react to information, the more reliant we become on System 1? Are we too quick to respond, leaning on our beliefs, intuition, and senses? But what does it mean to slow down and let System 2 kick in? Is it even possible to slow down a global society connected through a vast and complex digital network?

Or did the lethargy of the tools, technology, and social and political structures of the eighteenth and nineteenth century slow us down enough to reason and rationalize? Or maybe rational thought is an illusion. After all, these bi-modal cognitive scientists claim 98% of our daily cognition is System 1. We react, they claim, more than we ponder.

It was Daniel Kahneman who won a Nobel Prize for his advances in bi-modal cognitive research. It led to a best selling book called, “Thinking Fast and Slow.” But in subsequent interviews he reveals more nuance into what is happening. He’s beginning to believe our choice of beliefs and the words we use to describe them are more chance than anything. Kahneman asks,

“What does it mean to know something?...It has very little to do with actual evidence…it is anchored psychologically by the fact that other people you trust also believe in this thing. And it is only then that you invent reasons for it. It’s because the reasons that they cite for their beliefs have very little to do with their actual beliefs, which are usually informed by chance social factors.”

He claims it’s what makes people create nonsensical associative beliefs. For example, those who are against gay marriage also typically don’t believe in global warming. He says,

“It has an associative and emotional coherence, that’s all.” System 1. Emotion, intuition, and belief. Kahneman believes, for example, that “if you want to influence people about global warming, you have to speak to System 1 – we overestimate the influence of speaking to System 2. It’s quite disturbing when you realize people consider facts irrelevant.”

I’m no Nobel prize winning cognitive psychologist, but I question whether we can boil cognition down to two modes. But, I have no evidence; though others are collecting it. And in a global vote between ‘we’ and ‘I’, I doubt the ‘I’s’ have it. Just as our own eyes can’t see themselves, an “I” can’t be itself alone. The only way an eye can see an eye is by looking into the eye of another being. We did not come into this world alone, we did not survive birth alone, we did not learn to walk, talk, learn, or earn alone. And we’re not alone, around this world. Many, though not all, are on social media, blogs, newsletters, or podcasts writing and saying words that we believe – in volumes unparalleled in human history. We are alone together, bounded by words, tethered forever. Even if we are just echoing the people we trust.

The rise and fall of rationality in language. Marten Scheffer, Ingrid van de Leemput, Els Weinans, and Johan Bollen. December 2021.

Ibid

Individualism. Steven Lukes. March 2008.

Ibid

Ibid

American Individualism. Herbert Hoover, George H. Nash. 1922.

Ibid