Hello Interactors,

This week we continue to explore how maps played a major role in the shaping of America. Thomas Jefferson had a vision of a neatly portioned empire, just as the globe was neatly partitioned into a grid of latitude and longitude lines. Sure he wanted land for farmers, but he also needed to extract property tax revenue to fill the newly formed government’s coffers that had been emptied by the Revolutionary war.

The task of surveying and mapping fell on the shoulders of America’s first and only chief Geographer, Thomas Hutchins. Like most things in colonial America, it wasn’t easy.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or feel free to email me directly.

Now let’s go…

A BUNCH OF GRAPES

While Thomas Jefferson had grown accustom to the precision of his celestial and nautical instruments, surveying in the rugged American terrain was far from precise. The United States’ first official Geographer, Thomas Hutchins, was venturing into thick woods, mud bogs, and colonies of angry, disenfranchised inhabitants. And his motley crew of eight, out of the planned 13, may not have helped. It was an inauspicious start to Jefferson’s cartographic carving up of a countryside into covenants made of cunningly crafted cartesian corners. Meanwhile, George Washington’s war buddies wanted in on the land Hutchins was about to map out.

Hutchins and his men gathered in Pittsburgh in September of 1785 to head west for the Ohio River. As the first government organized and funded survey of public land, they were to map a grid of townships along the Ohio River known as the Seven Ranges. Of the eight men who showed up most were sent by wealthy prospectors, including founders of what was to become a few months later, the Ohio Company. This organization was loosely formed in Boston at the Bunch-of-Grapes tavern by a group of high ranking Revolutionary war veterans. This was more than a tavern. Bunch-of-Grapes was where power-broker backroom deals were made, slaves were traded, and land grabs were orchestrated. These men devised a scheme that would award them land in Ohio. They wrote it up and sent it off to the Confederation Congress who then granted them five percent of the southeastern corner of what was to become the state of Ohio.

Many of the men assigned to Hutchins were scouts for these land speculators. They weren’t interested in Jefferson’s plan to modernize and subdivide the country for the purpose of taxation, farming, and community building. Only one of the eight was truly qualified to survey alongside the experienced and capable Hutchins. The following list are the eight of 13 delegates originally intended to represent all of the colonies:

Edward Dowse: New Hampshire.

He actually wasn’t from New Hampshire, but Massachusetts. After the Revolutionary war he was involved in the East India Company and Chinese trade. He later served as a U.S. Representative.Benjamin Tupper: Massachusetts.

This state first appointed Rufus Putnam. Putnam is one of the founders of the Ohio Company. He declined because he had recently accepted the position of Surveyor General for lands in what was to become the state of Maine. Putnam requested that Tupper go in his place. It’s believed Tupper was mostly a scout for the Ohio Company.Isaac Sherman: Connecticut.

This post was initially offered to Samuel Parsons, another co-founder of the Ohio Company. So Parsons suggested Sherman. Isaac was the son of a founding father you’ve never heard of, Roger Sherman. He was an attorney about the same age as Benjamin Franklin and the only one to have signed Continental Association, the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution. Roger had just become the first mayor of New Haven, Connecticut, supported Jefferson’s idea of government acquired land as a revenue source, and was keen to settle the Connecticut Western Reserve – a block of land in what is now eastern Ohio.Absalom Martin: New Jersey.

Martin indeed was a surveyor and you can find his work archived at the Bureau of Land Management website. He most likely was there working on behalf of John Cleves Symmes. Symmes was a Revolutionary War Colonel and congressional delegate who had sent scouts to the Ohio territory in search of profitable land. He organized a group called the Miami Company. The U.S. Government handed over 200 thousand acres plus a 23 thousand acre township Martin was likely surveying. The Symmes Purchase included a village called Losantiville – later named Cincinnati. This area is also home to a curiously named university that many mistake for being in Florida – Miami University, also known as Miami of Ohio. It was one of the original eight Ivy League schools and is named, like the company, after the Miami Rivers in Ohio.William Morris: New York.

Morris was perhaps the one a true surveyor and mathematician at the level of Hutchins.Alexander Parker: Virginia.

Parker was a surveyor and woodsman who was comfortable navigating the frontier.James Simpson: Maryland.

Simpson was actually from New York and his affiliation or qualifications are not clear.Robert Johnston: Georgia.

Hutchins called him “Dr. Johnston”. He was a wealthy man from Maryland, but represented Georgia.

MATHEMATICIANS GONE WILD

A month prior to this crew assembling, in August 1785, the head of the Survey commission, Andrew Ellicott, hammered a wooded stake on the northwest bank of the Ohio River. It’s roughly where the Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Virginia borders come together at 40° 38’ 27” latitude and 80° 31’ 0” longitude west. This stick in the mud, a point on the globe, was the start of a line from which Hutchins would probe. All for a square, that a surveyor would sign, so a White man could claim, “This land is mine.”

It makes it sound easy, but it was anything but. Hutchins and his crew showed up with little more than compasses, a sextant, and a circumferentor. Also known as a surveyor’s compass, a circumferentor includes sights on the north and south sides of the compass. Looking through the sights, the surveyor lines up a point on the horizon in one direction and then another. They then measure the interior angle between the two. This was commonly put on a tripod with a lead-weighted plumb-line pointing at a reference point of origin marked on the ground in the center of the tripod. This would have been the modern-day version of the ancient Roman groma mentioned in an earlier post. And like the Romans, they also needed a way to measure distance between points. For that they used a Gunter’s chain with poles attached at each end.

While the Gunter’s chain was invented in England in 1620 by mathematician Edmund Gunter, who also invented what became the slide-rule – a Gunter’s scale, English surveying commonly used different instruments than these. Because much surveying was done unobstructed in fields, heavier and more precise instruments could be wheeled in place for surveying. Often with the assistance of the military. Surveyors in colonial America, however, often found themselves in mosquito infested, dense dark forests that merged with smelly swamps spilling into swift cold waters running through steep, rough, and rugged terrain. It called for improvisation.

In Silvio Bedini's book, Thinkers and Tinkers – Early American Men of Science, talks of the ingenuity forged by necessity among the self-taught thinkers and tinkerers of the European colonizers. He mentions in his book the contrast between the surveying context of these two competing and conquering countries:

"Land had to be cleared for settlements and roadways and rivers opened up for navigation, and surveying required techniques and instruments quite different from those traditionally used in England where the majority of areas were open."

John Love, a British surveyor who surveyed and mapped the Carolina’s in the 1600s, was instrumental in getting would-be colonial surveyors up to speed. In 1687, one hundred years before Hutchins’ and his crew set out for Ohio, Love published a book called, Geodaesia: or, The Art of Surveying and Measuring Land Made Easier. This was a popular field guide for surveyors throughout the colonial times. In the preface he hints at the challenges a naïve surveyor in America may run into:

"I have seen Young men, in America, often nonplus'd so, that their Books would not help them forward, particularly in Carolina, about Laying out Lands, when a certain quantity of Acres has been given to be laid out five or six times as broad as long."

Even in the seventeenth century, Love would have measured plats of land with a Gunter’s chain. Stretching 66 feet long, it’s made up of 100 wire links 7.92 inches long. Edmund Gunter’s clever math allows for easy multiplication and division by 10. One Gunter’s chain is equal to 22 yards which equates to 1/10th of an acre. Ten chains square is equal to one acre, and a single link is 1/100th of a Gunter’s chain. John Love’s book even provided a handy conversion table – but it also included a few lessons on rhomboids, chords, and trapezoids. It turned out trigonometry was sometimes needed to exact the measurements precise surveys required.

HUTCHINS LAST STAND

Surveying under these conditions was not a simple task and Hutchins had but one or two men capable of doing the math necessary to measure, calculate, and draw accurately. But precision is what the surveyor’s son, Thomas Jefferson, had in mind when he drafted the Land Ordinance’s of 1784 and 1785 – including the establishment and designation of the Geographer’s Line. This was an imaginary line from the point of origin, marked by that piece of wood lodged above the waterline in the bank of the Ohio River to another point forty-two miles due west along the meridian that encircles the globe.

Hutchins did his best to place himself and his crew at the exact place on earth where his measurements were to begin. He likely used his sextant to measure his location relative to the sun thus determining his latitude. But he documented the starting point as 40° 38’ 02” which is 22” off of the meridian – an error of nearly 1.5 half miles. The crew, in a hurry to make progress, then headed due west documenting one mile after another to establish the Geographer’s Line. Mapping historian and surveyor, C. Albert White, describes it in his book, A History of the Rectangular Survey System:

“Between September 30 and October 8, 1785, Hutchins, the other 8 surveyors, and a crew of about 30 chainmen and axemen ran 4 miles of line west from the beginning point. The line was run with a compass or circumferentor, with orientation at each point by using the compass needle, and measured with a two-pole Gunter's chain held horizontally. A post was set at the end of each mile. Bearing trees were taken and scribed using either a carpenter's race knife or cooper's (barrel maker's) knife. At the rate of $2 per mile, the crew only earned $8 for nine day's work. On October 8, 1785, Hutchins stopped work because he had word of Indian trouble at Tuscarawas, 50 miles to the west. Though Hutchins made an elaborate report of these four miles of line to the Congress, it was nevertheless a very poor showing for the year.”

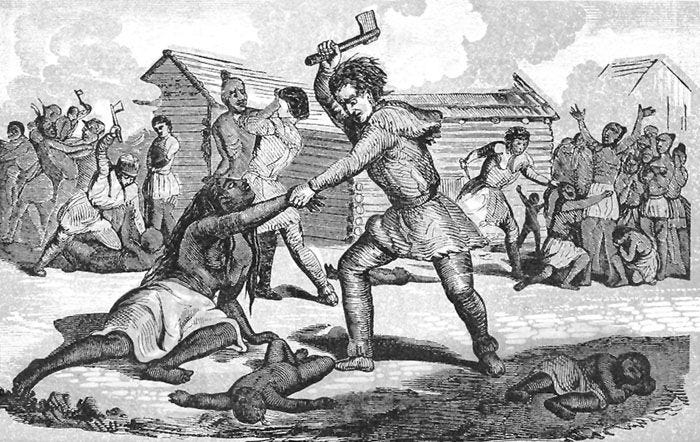

Fifty miles may seem a fair distance away to be of concern, but this Ohio region had become the new frontline of resistance to settler expansion westward. There was also lingering British competition for land. Just three years prior, in 1782, George Washington dispatched Philadelphia minutemen to the Ohio frontier to exact revenge on raids from angered Indigenous tribes in Pennsylvania. Not far from the soon to be west end of the Geographer’s Line, the militia happened across a group of nearly one-hundred Lenape people tending to their corn. The troops surrounded them and took aim with their muskets. The Lenape froze and pleaded their innocence with the men. The soldiers held a vote as to whether they should killed these peaceful, defenseless people or not. Seconds later 96 Lenape people lay dead. Massacred.

These Lenape were known as Christian Lenape and had just returned to their homeland after having been driven north by competing British-allied tribes a year earlier. The Christian Lenape dated back to the early 1700s. A group of Christian Moravian missionaries, originating from the present day Czech Republic, found a small group of Lenape people following them after their tribe had nearly been exterminated by small pox. The missionaries took them in and converted them to Christianity. Colonial Moravians settled far from others to protect their followers from the tension that emerged from competing religions, native conflict, and colonial settlement. By the late 1700’s they had moved to the Ohio frontier to escape the very violence that ended up taking their lives.

Despite Hutchins’ disappointing start to the mapping of the Seven Ranges, he returned on August 9th, 1786 with six of the original delegates and six more were added. Hutchins picked up where he left off and began running due west to create the Geographer’s Line. After measuring six miles from that stick in the mud on the northwest bank of the Ohio River, he sent Absalom Martin due south toward to a bend in the Ohio River. This was to be range number one of seven. At the next six mile juncture, he sent Adam Hoops of Philadelphia south, then came Isaac Sherman, then Ebenezer Sproat of Rhode Island, then Winthrop Sargent who had replace Edward Dowse, then James Simpson, and finally the two most capable surveyors and mathematicians took ranges six and seven: William Morris and Thomas Hutchins.

Hutchins, again, was forced to retreat due to Indigenous resistance. By the middle of October, Winthrop Sargent had finished most of the fifth range, but was also forced to retreat. Hutchins was now short on time. He directed six of the men to complete east-west lines in order to complete at least some townships. By the middle of November 1786, four ranges of townships had been completed. They spent the next two months drawing and detailing their maps. Hutchins then left a frigid Ohio back east to New York for his presentation to the Board of Treasury of their progress.

In April of 1787 Ludlow and Martin returned to Ohio and then Simpson soon after. Ludlow hastily finished the seventh range in two weeks. Harassed but not deterred by native resistance, Simpson and Martin were able to complete ranges five and six soon after Ludlow. While their work was wrapped up by June 1787, the Board of Treasury in New York did not receive final maps and plats until July of 1788. By then Congress had grown impatient and between September and October of 1787 had already sold land on those first four ranges Hutchins and his crew completed in the final months of 1786. Hutchins returned again to Ohio in the fall of 1788, then traveled home to detail his work, and on April 28th, 1789 he died.