Hello Interactors,

After enduring a few days of record heat that burnt my drought tolerant plants to a crisp and likely claimed the lives of two of our favorite wild birds that would frequent my daughter’s window feeder, my new pair of shoes arrived I had ordered from Canada. As did a new monitor and other odd consumer goods. And soon I will be boarding a plane that will spew another chunk of the estimated 22 tons of CO2 our family will contribute to the atmosphere this year. That’s four and a half hot air balloons full. I know I’m heating up the planet with my shoes and trips. You probably do to. It seems we not only need to protect the environment, we need protection from ourselves.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

THE RIVER’S ON FIRE

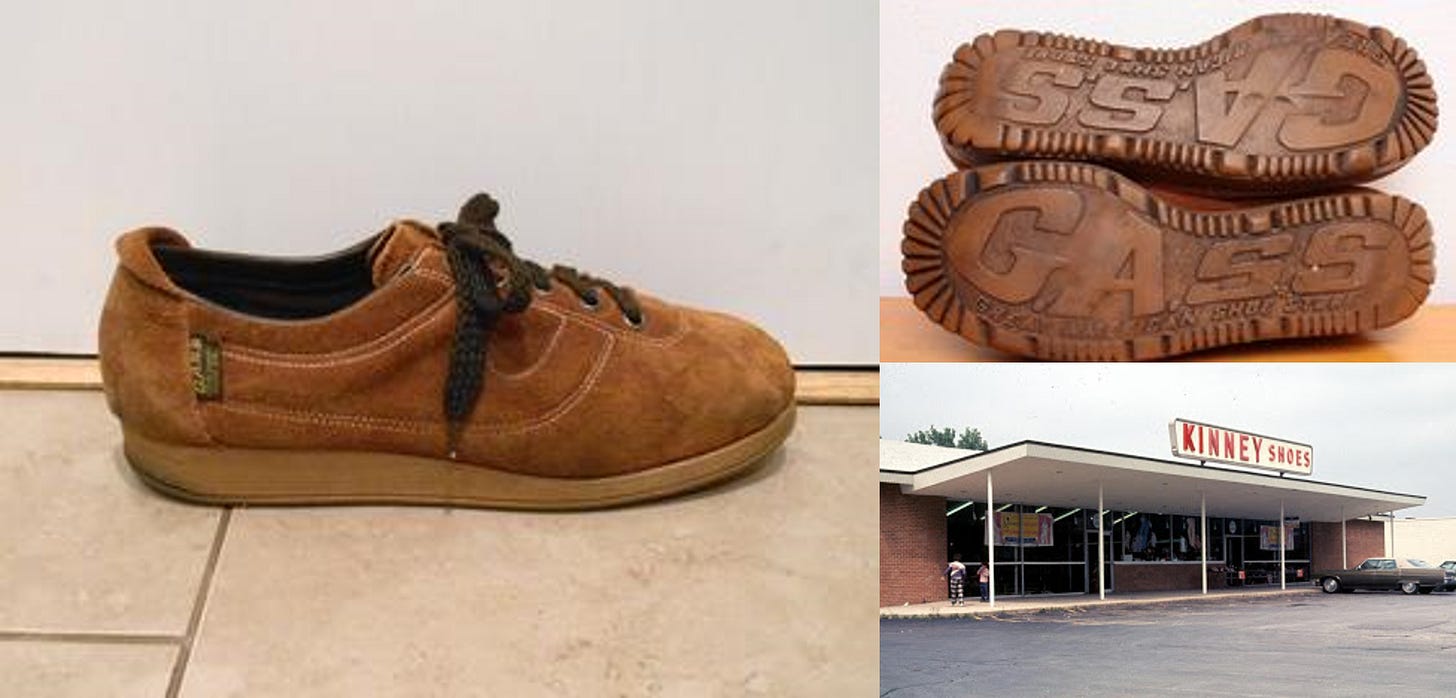

As an early teenager in the 1970s, just entering middle school, I remember getting a pair of “Earth Shoes” as part of my back-to-school get up. They featured a tread that read, “GASS”, which stood for Great American Shoe Store. Most, if not all, of our shoes back then came from the Great American Shoe Store – Kinneys. I felt pretty cool in my new kicks; especially when that first snow fell and I could see the GASS imprint in my foot tracks. Gas was on the minds of many in the 70s, as it was becoming increasingly hard to come by. It was also increasing pollution.

Kinneys was capitalizing on a burgeoning environmentalist trend that had been growing since the publishing of Rachel Carlson’s, Silent Spring in 1962. By 1970, water and air pollution was prevalent, the federal government was forced to intervene. On January 1st, 1970 the Council on Environmental Quality was created with the signing of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This requires Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) of all federal agencies who are planning projects with major environmental ramifications.

Either recognizing they may be a target of the government or perhaps seeing consumers being drawn to environmentalism, the American auto makers also got in on the environmental action. A January 15th New York Times article read, “Detroit has discovered a word: “Environment.”” The General Motors (GM) CEO, Edward Cole, promised an “essentially pollution free car could be built by 1980.” Engineers from GM, Ford, and Chrysler attending the 1970 convention of the Society of Automotive Engineers were all pitching anti-pollution technologies. GM’s CEO was probably influenced by his son, David Cole, who was an assistant professor at the University of Michigan. He co-authored a paper for that convention entitled, “Reduction of emissions from the Curtiss Wright rotating combustion engine with an exhaust reactor.”

There was growing concern entrusting those very institutions responsible for the destruction of the environment with devising schemes to save it. The country’s air, water, and land was being smothered in waste. Something needed to be done. So on July 9th, 1970, 51 years ago today, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was proposed by Republican President Richard Nixon.

This agency was intended to focus on short-term fixes targeting violators of the law, so Nixon appointed Assistant Attorney General, Bill Ruckelshaus, to the post. Ruckelshaus promptly ordered a steel company to stop dumping cyanide into Cleveland, Ohio’s Cuyahoga River. It was so polluted that it had caught fire at least thirteen times. Ruckelshaus also banned the use of DDT.

After being jostled around in various appointments and governmental positions, including the head of the FBI, he was reappointed to head the EPA in 1983 by Republican President Ronald Reagan. The Reagan administration grew concerned over the faltering reputation of the EPA after Ruckelshaus’ replacement, Anne Gorsuch Burford, (Neil Gorsuch’s mom) cut the EPA’s budget, eliminated jobs, and neutered enforcement policies. The EPA and the environment was slipping backwards, so once again it was Ruckelshaus to the rescue. He promptly fired most of her leadership team and got back to work protecting the environment running the EPA until 1985.

Upon leaving government, Ruckelshaus moved to Seattle and was a practicing attorney and continued to prosecute environmental crimes. In 1993, Democrat President Bill Clinton appointed him to the Council for Sustainable Development and throughout the 90s he worked as a special envoy in the Pacific Salmon Treaty between the United States and Canada and was chair of the Salmon Recovery Funding Board. Republican President George W. Bush then appointed him to the United States Commission on Ocean Policy in 2004. The commission was terminated that same year but in 2010 became part of the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative which Ruckelshaus co-chaired. Ruckelshaus endorsed Barack Obama in 2008 and Hillary Clinton in 2016 and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Obama in 2015. Nearly fifty years after being appointed by a Republican president to become the country’s first EPA administrator in 1970, fighting for environmental justice at the international, federal, state, local levels – and in the private sector – Ruckelshaus passed away at his home in my neighboring town, Medina, Washington in 2019.

FROM DUST TO THE SEA WITH WALLY AND ERMALEE

When the Nixon administration created the EPA, they decided to put it under the Department of the Interior. This executive department’s mission is to, “protect and manage the Nation’s natural resources and cultural heritage; provide scientific and other information about those resources; and honor its trust responsibilities or special commitments to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and affiliated Island Communities.” For the first time in our nation’s history, it is headed by a person indigenous to these natural resources and cultural heritage; native American, Deb Haaland. The department dictates how the United States “stewards its public lands, increases environmental protections, pursues environmental justice, and honors our nation-to-nation relationship with Tribes.”

When the EPA was created in 1970, the Secretary of the Interior was Alaskan land developer and politician, Wally Hickel. Instead of creating a separate administration for the EPA, Hickel urged Nixon to fold the designated 15 offices under the Department of Interior and rename it the Department of the Environment. It’s hard to know if Hickel’s suggestion was genuinely thoughtful or an egoist attempt to gain power. After all, Hickel was a controversial pick for the post of Secretary of the Interior in the first place. Many activists, journalists, and even the Sierra Club, mounted campaigns to thwart his appointment.

Walter Joseph “Wally” Hickel was born in Kansas in 1919 where he and his family endured both the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. Given the heat waves this summer, we’d be wise to reflect more on the Dust Bowl. It’s was the era’s most devastating man-made environmental disaster. Stripped of their native grasses by cattle and sheep or farmers making room for wheat, White settler farmers ignored Indigenous dryland farming methods that used the grasses to anchor, moisten, and nurture the fervent soil – even during droughts. When a record drought swept across the country and the wheat dried up, farmers tilled it under. Void of organic matter the land became susceptible to the winds sweeping across the plains.

The term “Dust Bowl” came from Denver based Associated Press writer, Robert Geiger, reporting on his own personal account of a particularly pernicious dust storm. On April 15th, 1935 he wrote,

"Three little words achingly familiar on a Western farmer's tongue, rule life in the dust bowl of the continent—'if it rains.'"

He was reporting on a severe dust storm that occurred the day prior – “Black Sunday”. “Black blizzards” of dirt and dust hurled themselves across Oklahoma south to Texas lifting and mislaying an estimated 300 million tons of topsoil. Dust storms such as this went on from 1935 to 1941 sucking soil particulates from the ground darkening the skies in clouds of dust that blew as far east as Maine. It also scattered people in all directions across the country in a climate migration crisis of their its own making. Wally Hickel was one of the displaced.

Wally was an athlete in High School and taught himself how to box by watching newsreels of Joe Louis. He became the Class B Golden Gloves champion in 1938 at age 29. Two years later he found himself in California fighting the welter weight champion, Jackie Brandon. Brandon broke his nose in the first round, but Hickel knocked him out three rounds later. Evidently struck by wanderlust, Hickel wanted to then hop a ship headed for Australia but lacked a passport, so instead he boarded the S. S. Yukon headed for Alaska.

He returned to Kansas and married, but lost his first wife to illness. He worked as an airplane inspector that included occasional trips to Alaska to inspect privately owned planes – including Russian planes. It was in an airplane hangar that he met his second wife, Ermalee Strutz, and moved to Alaska. Hickel described her as “beautiful as a butterfly, but as tough as boots.” Her father was a United States Army Sergeant stationed in Anchorage and her family had ties to Alaska’s largest financial institution – National Bank of Alaska. She pushed Wally to enter the race to become Alaska’s second Governor.

Hickel struggled with dyslexia, so Ermalee was tasked with doing most of his writing, including his campaign speeches. She remained a powerful influence on his career, including pushing Hickel to support the Alaska Permanent Fund. This is a state-owned corporation that invests at least 25% of the money flowing through the Trans-Alaska Pipeline in a fund that sends dividend checks to each resident of Alaska. In 2019, this yielded an annual check in the sum of $1600. This government run basic income guarantee was devised, implemented, and executed by a string of conservative Republican Governors starting with Wally in 1966 and continues today with the Republican far-right Christian conservative, Mike Dunleavy. Maybe this is where liberal socialist-leaning politicians like Bernie Sanders got the idea for a nationwide Universal Basic Income.

In 1968, Hickel was told by Nixon that he would have to leave his post as Governor of Alaska to become the Secretary of the Interior. Wally cried. He probably cried again two years later when Nixon fired him for his “increasingly militant defense of the environment.”1

Hickel led a string of pro-environment policies in his short two years as Secretary:

Preserved some of the Florida Everglades: He established the Biscayne National Monument preserving the ecological development of 4,000 acres of keys and more than 90,000 acres of water in the bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

Delayed the Alaska oil pipeline to study its effects on permafrost: Heat generated from the pipeline would melt the permafrost leading to unknown damage to the ecosystem and the piping system.

Halted the drilling of oil in the Santa Barbara channel: After a 1969 oil spill, Hickel removed 53 square miles of federal tracts from oil and gas leasing. (Later Reagan hoped for more platforms to be built in the channel because he liked how they reminded him of Christmas trees flickering in the dark. Locals call the oil rigs Reagan’s Christmas Trees)

Cracked down on oil companies in the Gulf of Mexico: After this oil spill in the gulf, also in 1969, Hickel asked the Attorney General John Mitchell (the man who recommended Ruckelshaus for the EPA position) to convene a grand jury to investigate violations by Chevron and 49 other companies in nearly 7,000 oil and gas wells in the Gulf of Mexico.

Stopped imports of commercial whaling products: After placing eight species of whales on the Department's Endangered Species List, Hickel halted imports of oil, meat and any other products from these species. In 1969, roughly 30% of the nation’s soap, margarine, beauty cream, machine oil, and pet food came from whale oil.2

The final straw for Nixon was Hickel’s public opposition of the administration’s policies on the Viet Nam war and their fatal handling of the Kent State student protests. Hickel wrote,

“I believe this administration finds itself today embracing a philosophy which appears to lack appropriate concern for the attitude of a great mass of Americans – our young people."

Hickel was promptly let go. With him went the Assistant Secretary of the Interior, Dr. Leslie Glasgow, who was in charge of Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources. Glasgow took a leave of absence from Louisiana State University, where he taught marsh wildlife, to assume his post under Hickel in Washington, D.C.

He exceled at educating, convincing, and cajoling corporations, companies, and governmental agencies into environmental conservation practices. He was loved by both hippies and hunters and represented widespread hope that the nation could finally begin to heal the land it had wrongly wounded. But those hopes were dashed when it became clear Nixon would rather appease corporations than heal the environment.

In a December 12th, 1970 New York Times article Glasgow said he was

“pushed out of the Department of the Interior by political and business interests in a shake up that represented a “definite step backwards for environment.””

In anticipation of running for a second term in 1972, Glasgow supposed Nixon thought “the changes and dismissals had been made early in hopes that the people would forget them before the Presidential campaign.” What everyone remembers, is not what Hickel and Glasgow did for the environment but what Nixon did to himself and the country as the first evidence of the Watergate Scandal started the summer after their firing.

AMERIGNIGMA

Glasgow went back to teaching and Hickel went back to real estate. He was not about to make the same mistake his dad made in not owning property, so he bought as much as he could. He started Hickel Investment Company that is now run by this son, Wally Jr. They own and operate hotel rooms, food and beverage outlets, office and retail spaces, and residential lots around Alaska. They, like all residents of Alaska – including poverty stricken Indigenous tribal members – benefit from increasing profits from extractions of natural resources like oil and fish.

It makes me question Hickel’s sterling environmental track record as Secretary of Interior – a post that demands a lot of reading and writing. Perhaps he relied heavily on, and was influenced by, his environmentalist and academic assistant secretary, Dr. Glasgow. Maybe he diddled a dyslexic Hickel into an environmental clinician the same way his wife shaped him into a politician. Especially if Glasgow was known for his ability to convince corporations that doing good for the environment was also good for business. After all, conservation and conservative are just two letters apart.

The United States is an enigma when it comes to mixing environmental stewardship with commercial profits. The EPA and the National Park Service sit under the Department of Interior which “manages public lands and minerals, national parks, and wildlife refuges and upholds Federal trust responsibilities to Indian tribes and Native Alaskans. Additionally, Interior is responsible for endangered species conservation and other environmental conservation efforts.” But the Forest Service sits under the Department of Agriculture which “provides leadership on food, agriculture, natural resources, and related issues.” Meanwhile, the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) sits under the Department of Commerce which “works with businesses, universities, communities, and the Nation’s workers to promote job creation, economic growth, sustainable development, and improved standards of living for Americans.”

Like all slaves to fashion, I likely ditched my eco-kicks in favor of the next cool shoe. Probably a new pair of 1978 Nike Tailwinds, the first to feature an air pocket. They too had a cool tread first made from a waffle iron. I don’t recall what kind of imprint they left in the first fallen snow, but I know now the imprint my habitual consumerism has on the environment. And I need help.

Environmental protection, conservation, and restoration are necessary to limit the greed that seems to overcome both producers and consumers of limitless goods made from limited resources. Over zealous consumerism will not be quelled by collective action on the part of consumers. Leaders need to lead and act on behalf of future generations of both humans and non-humans. That’s what it means to lead.

The dirt from “Black Sunday” filled ponds and potholes across the plains decimating duck and other wildlife populations. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a fervent Democrat, hired a Republican to remedy the calamity. He appointed the famous, well loved Iowa cartoonist and conservationist “Ding” Darling to head the U. S. Biological Survey – what then became the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Department of the Interior. He created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) putting 2.5 million young people to work restoring natural wetlands and habitats along the nation’s four major flyways. More than 63 national wildlife refuges were established during the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. That’s what leadership looks like, America, in the face of a man-made climate crisis.

https://environmentalhistory.org/20th-century/seventies-1970-79/

ibid