Hello Interactors,

It’s been a troubling week in international news as we all watched Afghanistan unravel. That country has been through a lot over the last two decades and centuries; most of which is due to Western invasion and intervention. To make matters worse, the effects of climate change are compounding their problems. I hope we can learn how to better help, they’re going to need it.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

GOING SOLAR

Soon after absorbing the tragic scenes in Afghanistan this week, I was reminded of an article I read around this time last year. It was about successful deployments of solar technology by poor Afghan farmers to pump water from desert wells to grow crops. Afghanistan ranks among the lowest on the Global Adaptation Index making them one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change. As if they needed more problems.

Solar energy can be transformational, even when deployed at small scales. We’re not talking about massive solar farms plastering the desert paid for by corporations, governments, or non-governmental organizations (NGO) through some kind of ‘Go-Green’ initiative. These are installations by rural farmers struggling to survive. The first remote solar array was notice back in 2013, but soon local towns were piled high with solar panels.1

The panels are not cheap. Seed money usually comes from a dowry – money given from a bride’s family to the groom at the time of marriage – which is roughly $7,000. A single solar panel costs $5,000, so it’s a big chunk of money. But the panel pays for itself in just two years. They simply set it up, plug it into the provided pump, kick aside the old, expensive, and troublesome diesel motor and watch the water come streaming out of their well.

The number of solar panels has doubled every year since 2012 tapping wells far into the desert. By 2019 there were over 67,000 installations dotting a single narrow region in southern Afghanistan. And for every diesel conversion to solar comes an increase in productivity. The blue areas of these maps show less productive cultivation and light green as more productive. In addition to the increase in the number of farms, you can also see an increase in yield. Their success attracts even more people to the desert. Between 2012 and 2019, 48,000 new homes were built. Increased competition for a water supply that climate change has already diminished, the introduction of solar pumps has started a countdown clock as to when they’ll all run out of water.

Which, in one way, may be a good thing. While one of the crops farmers choose to grow in the desert are sun hungry plants like tomatoes, their main, and most profitable crop, is opium. The majority of opium is refined to make heroin. Afghanistan is the world’s leader in opium production making it the leading source of heroin, one of the most illicit addictive drugs there is. And this region of Afghanistan, Helmand, produces 80% of the Afghan supply to the world. Most of it to Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.2

Before solar entered the fray in 2013, Afghanistan was producing 3,700 tons of opium a year. By 2017, a record year, their production nearly tripled to 9,000 tons. It created a glut in the market and prices fell, reducing production among farmers still on the more expensive diesel pumps. Meanwhile, solar farmers continued to produce and profit at 2017 levels.3

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED : MISSION ADMONISHED

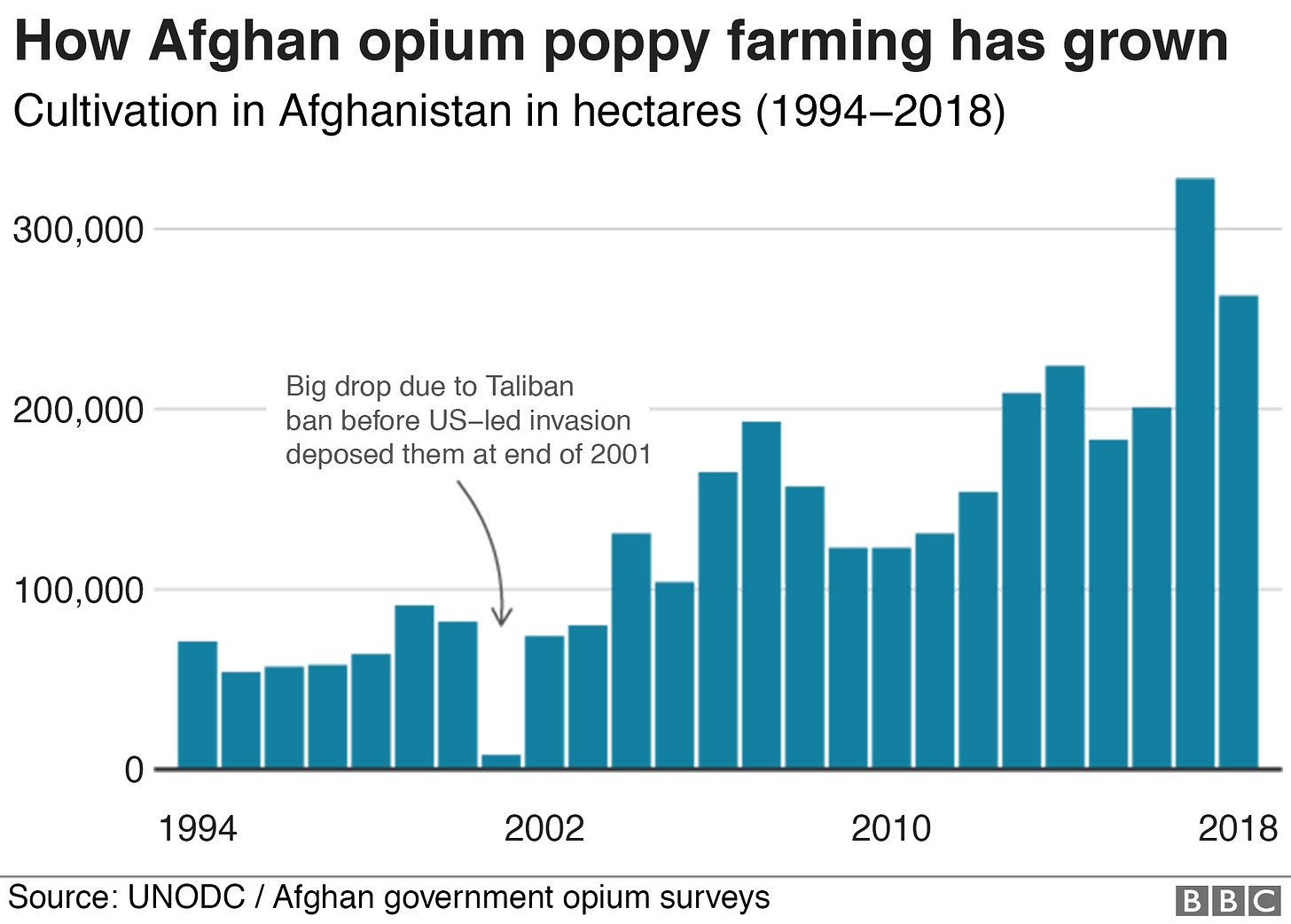

The opium market has been growing in Afghanistan since the 1990s, with the exception of one outlying year – 2001. That was the last time the Taliban took control and one of their many bans was on growing opium.

When the United States infamously invaded Afghanistan in 2002, opium production quickly bounced back to pre-Taliban levels, and has been growing since. England joined in the invasion, in part to curb the supply of heroin to the UK and other parts of Europe. They’ve found that as production of opium increases, the demand for heroin also increases; and with it crime as addicts resort to breaking and entering and aggravated assault to fund their habit. England’s biggest war casualties occurred in the region of Helmand, the world’s hotbed of opium and the country’s highest concentration of solar panels.

What a bitter twist of wartime irony this is. Britain was the first country from the West to invade Afghanistan in the mid-1800s; in part to increase the production and trade of opium to the Chinese through the East India Company as part of the Opium Wars between Great Britain and China.

Opium in China was first used for medicinal purposes, but by 1840 millions of Chinese were addicted. The United States saw this as an opportunity and a few decades later were dropping cigarettes from airplanes in China in an effort to supplant the Chinese addiction to opium with an addiction to nicotine. Journalist and East Asian writer, John Pomfret, notes that in the

“1890s, only a few people smoked. By 1933, the Chinese were puffing on a hundred billion cigarettes a year, more than any other nation except the United States.”4

Great Britain invaded Afghanistan from India, a country they colonized a century earlier. Still smarting from their failure to gain control in the Americas, they reluctantly turned to the east. To conquer Afghanistan, they enlisted poor Indians as low ranking infantry and invaded Afghanistan in 1839. The British claim they were fearful the Russians would take control of this strategic trading route, but Afghans on the ground tell a different story. It seems what the British were really worried about was parts of India being invaded by growing numbers of Persians and Afghans who opposed British imperialism.

Indians put up a fight when England invaded India, just as Indigenous Americans did. Afghanistan was no different. War is ugly by any dimension, but the Europeans (and Americans) have an established reputation among victims of invasion for being particularly ruthless. Much attention is given to the atrocious behavior of the Taliban against women, but very little to none is given to how British, and their low ranking Indian infantrymen, treated women upon invading Afghanistan. Women of this region were formidable fighters during this time, leading thousands in battle and inspiring many more through poetry to take arms in defense of their homeland from encroaching colonial imperialists.

In 2018, Farrukh Husain, a Muslim Afghan history researcher, published a book called Afghanistan in the Age of Empires: The Great Game for South and Central Asia. It is one of the few, if not only, books written by a Muslim Afghan for a Western audience about the history of this region as told from someone with ancestral ties to these events. He reveals the power and leadership Afghan women held in those days. He writes of a battle near Helmand, where solar panels now dot the desert,

“…no contemporary author has written about the first such charge by a burka clad woman against the British, during May 1842, to avenge her husband’s death at the head of thousands of Afghans, which took place…in…Helmand.”5

One month later, on June 17, 1842, British Brigadier General Thomas Monteath led troops into a peaceful remote village called Ali Baghan where they proceeded to rape and plunder.

The English language newspaper out of Calcutta, India, the Bengal Hurkaru, reported,

“To ravage and burn villages, and to violate the women inhabiting them, are not precisely the best measures calculated to restore the honour of Great Britain. We talk about national disgrace, and begin ravaging villages and violating helpless women, as though any misfortunes could disgrace us so irredeemably as these crimes. A miserable hamlet about six miles from Jellalabad, on the Peshawaur side, is assailed by a brigade of British troops, who happen to find some accoutrements belonging to the men of the 44th; the village was given up to plunder, the women were violated, and the tenements burned.“6

Atrocities like this and violence against women continue to this day in Afghanistan. The United States is no better as evidenced by the methods of torture throughout the United State’s so-called ‘War on Terror’. And while we continue to be bombarded with stories through Western media about how the United States was in Afghanistan helping to liberate Afghan women, I suggest you read this May 2021 article by Farrukh Husain as an alternative and local narrative.

Or if you have trouble trusting a Muslim Afghan man writing on Afghan women, check out this bit of ethnographic research from Dr. Teresa Koloma Beck, called Liberating the Women of Afghanistan: An ethnographic journey through a humanitarian intervention where she asserts the West’s

“humanitarian engagement further politicized the category of gender and, hence, amplified its importance. Yet, as in other places of the world, it also served to perform and reproduce ideal-typical images of the Western Self.”7

CLIMATE MATTERS MORAL TATTERS

Climate change is expected to bring more unrest to Afghanistan and areas like it around the world. One report from the United State’s National Institute of Health reports, “both short-term shocks, such as natural disasters and associated losses of livelihood opportunities, as well as longer-term stressors, such as growing scarcity of resources associated with drought, can increase the risk of instability.” That instability can include armed conflict, as evidence by one Syrian conflict that “at least partially driven by drought, has, estimated conservatively, resulted in over 143,000 deaths as of 2016.”

These poor countries will need the help of rich countries if we care at all about saving the lives of humans and non-humans alike. But the West has to reckon with our past if we’re to be trusted with the future. We’re not very good at owning up to our mistakes or rubbing our own noses in the atrocities we inflicted on innocent people through an unbridled need to perpetuate our greed. Claiming moral superiority while killing people already suffering the effects of climate change – as Obama did with over 540 drone strikes during his presidency – should make us pause and reflect on our ethical standing. Whether it’s in the name of God or in pursuit of gold, the United States (and many other countries, clans, and conquerors) have a way of conveniently justifying colonial conquest, rape, abduction, torture, slavery, or genocide.

The 18th century English feminist writer and philosopher, Mary Wollstonecraft, put it efficiently and accurately when she wrote:

“No man chooses evil because it is evil; he only mistakes it for happiness, which is the good he seeks.”8

To sell our message of ‘good’, the United States also has what our victims of evil don’t have; a well crafted and well funded media machine – spanning the political spectrum – to lull the masses into a sometimes angry and sometimes celebrated, numbing complicity. But like any addiction, the more you feed it the harder it is to break. And this country, and our military, is addicted to aggression.

But Norway is one country that is taking a step back. As current chairs of the UN Security Council they issued a public statement on the recent plight of Afghanistan on August 16th asking the international community to be “willing and able to relate to, co-operate with, and support a future, new Afghan government in which the Taliban participates.”

But long before that, sensing the confluence of social and climate induced unrest and reflecting the West’s track record on foreign interventions, the Norwegian Minister of International Development funded research to better understand the successes and failures of climate mitigation strategies and efforts from the West. Their report titled, Adaptation Interventions and Their Effect on Vulnerability in Developing Countries: Help, Hindrance or Irrelevance?, came out in May of this year.

The study’s highlights read like this:

“Adaptation interventions may reinforce, redistribute or create new vulnerability.

Retrofitting adaptation into existing development agendas risks maladaptation.

Overcoming these challenges demands engaging more deeply with the local context of vulnerability.

Real involvement of marginalised groups is required to improve use of climate finance.

Unless adaptation is rethought, transformation may also worsen vulnerability.”

What they found among the 60 internationally-funded interventions aimed at climate change adaptation and vulnerability are four consistent themes:

Shallow understanding of the context of local vulnerability;

Inequitable stakeholder participation in both design and implementation;

A retrofitting of adaptation into existing development agendas;

A lack of critical engagement with how ‘adaptation success’ is defined.

Inequality is evident everywhere we look: income, race, religion, gender, social status, cultural norms, transportation, and so many more. Add to that environmental inequality. What these researchers concluded is that unless we start by first focusing on equality, no amount of government, private, or corporate funding of technological or financial fixes will matter. For example, building a sea wall, dam, or dike to stem flooding rivers or rising seas can easily be celebrated and manipulated into appearing to make progress on climate change. But if those efforts steal water from an Indigenous tribe, or limit physical access to schools of disadvantaged families, then simply throwing money at them or subsidizing a move to the city does not constitute an equitable solution that is sensitive to their local context of vulnerability. But it’s easy to see where such engineering feats would fit an existing corporate or governmental agenda, possibly even win sustainability awards, or get endorsed by a Western celebrity complete with a selfie that goes viral.

Don’t get me wrong, getting solar technology scaled to the point where a poor Afghan farmer could afford it is a marvel of technology and a demonstration of the positive effects of innovation in free-market capitalism. But if it also results in the increase of heroin worldwide, how can we feel good about the outcome? The vast majority of heroin in the United States doesn’t come from Afghanistan, it comes from the deserts of Mexico where surely solar pumps are also being sold. In 2018, marijuana sold for $80 per kilogram in the United States.9 Meanwhile, heroin sold for $35,000 per kilogram. What would it take to persuade those Mexican farmers to grow vegetables instead of opium? And what kind of moral standing can America have as we lead the world in drug disorders and are the number one consumer of opioids – with heroin as the second leading cause of overdose behind pain relievers.

Afghan women are number two behind United States women in drug disorders. Is that what we mean when we claim we liberated Afghan women? Few women in Afghanistan, especially under Taliban rule, have access to their own land; a clear inequality that needs addressed. But there was a bright spot for Afghan women and farming in recent years in a good example of what appears to be a more equitable climate intervention.

Ghuncha Gul, and Afghan farmer, always dreamed of owning her own farm. With the help of the United Nations Development Program she fulfilled that dream in 2018 by offering her training, land, and resources for her own greenhouse and beehives. Her village friends now affectionately call her ‘honey’ عسل. She proudly admitted,

“Women in villages work just as hard as men. In fact, we work alongside the men." Two hundred years ago, she just may have been leading the men.

As money wielding climate adaptation efforts take shape by the privileged and powerful around the world, let’s ensure people like Ghuncha are given equal rights and their knowledge and customs are understood and respected. In the process of co-designing and implementing climate adaptation strategies in the context of local inhabitants of their land, let’s also make sure we leave the exchange more enlightened than the Age of Enlightenment, more righteous than Western imperialism, and more informed than the Western propaganda machines leave us believing we are. Maybe if we do, these people will return the favor when we discover our own crisis have left us equally, if not more, vulnerable.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Pomfret, John. The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom: America and China, 1776 to the Present (p. 177). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Ibid.