Hello Interactors,

While the media dwells on border disputes like Russia and Ukraine or Trump’s wall, COVID, climate change, and the global economy thumb their nose at territorial boundaries. Are these borders we obsess over even real or are they products of our imagination?

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

A CASTLE WITHOUT HASSLE

On Sunday I pulled the beast from the closet. It had been awhile. Probably too long. It pulls with a heaviness that always takes me by surprise. Its long neck, standing tall above its body, awkwardly slumped over my shoulder as I drug its head from the darkness. I walk down the hall with its neck strung out behind me tugging on its short, stout resistant body that pressed heavy with resistance.

I don’t know why we keep it. Nobody in the family likes it. It’s not that it eats incessantly; that’s why we got it. It’s more that it’s so damn heavy and awkward. No wonder we keep it in the closet longer than we should. But there’s only so much dust and dirt one can tolerate in a house. It was time to vacuum.

We tolerate a fair amount of dust in our house. Lazy? Maybe. Is it so bad that we let a little dust accumulate? As the comedian George Carlin once said,

“Dusting is a good example of the futility of trying to put things right. As soon as you dust, the fact of your next dusting has already been established.”

I grew up, like many people I suppose, learning to have anxiety around dust accumulation. But I was raised Methodist and it was John Wesley, Mr. Methodism himself, who most likely coined the phrase, “cleanliness is next to godliness.” He had a thing about remaining clean. But this idea dates back to the Old Testament. Cleanliness for the Hebrew people wasn’t about the home, it was about the body. That’s how we got baptism, foot washing, hand washing, and, yes, circumcision. Either way, to be clean was to be pure.

By dragging this weighty, electrified, menace with its dust breathing head across floors, window sills, and furniture I am not only sucking up undesirables into a bag, I am purifying the home. And just to make sure these impurities don’t escape the menace of this machine it features a HEPA filter on its exhaust. Why do people feel the urge to purge these dusty hombres from our home?

There are practical reasons, I am sure, just as with washing our bodies. But it’s different with our homes. These unwanted microscopic interlopers have made their way inside our home and we want them outside our home. As they invade we become territorial. We sweep dust into a bin, under the rug, or out the door. There is a spatial differentiation to ‘cleansing’ the home of ‘undesirables’. Get out and stay out!

As a child, were you not allowed to take food into certain rooms? Do you take your shoes off at the door? How about, “No pets upstairs!” Growing up I had friends where entire living rooms were off limits to kids. Parents are known to issue all kinds of spatial regulations to their families. “Go to your room!” “Get out of the kitchen!” “Take it outside!”

But rooms can also house fond thoughts. Some of my best memories were in my basement. I played pool, the piano, and with trains. I watched home movies, made art, or pulled an Encyclopedia from the shelf and was transported to another world. I told this story to someone on a Zoom call last week and they leaned into the camera looking not at me but around me and asked, “And where are you now?” “In my basement”, I replied.

But not everyone has fond memories of their homes. If they had one. For victims of spousal and/or child abuse, or even slavery, recalling memories of home – or certain rooms in a home – brings on discomfort, anxiety, and pain. Response to that anguish varies by person.

The influential feminist author, professor, and social activist bell hooks (a pen name borrowed from her grandmother’s name Bell Blair Hooks and reduced to lower case out of deference) writes in her book Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics that black women, during her childhood in the south,

“constructed their homes as places of care, nurturing and retreat from a harshly racist society in which most of them also worked outside their own homes, in domestic service at the homes of white people.

Making their own home, hooks believed, however modest or temporary had ”radical potential” to regain “their ‘subjectivity’ (their personal human identities) in a society which tended to categorize them oppressively by gender and ethnicity as ‘women’ and ‘black’.”1

This interpretation of and relationship to ‘home’ can be complex. For some “a man’s home is his castle” so long as ‘he’ is the ‘master’. This phrase first read as “An Englishman’s home is his castle.” Which is to say “An English person’s home is a place where they may do as they please and from which they may exclude anyone they choose.” It was popularized after appearing in the book The History of the Norman Conquest of England in 1868 by the English historian Edward Augustus Freeman. However, it had been ensconced in British law since 1505. The law read,

“If one is in his house, and he hears that such a one wants to come to his house to beat him, he can well make an assembly of folk among his friends and neighbours to assist him, and to aid in safeguard of his person...”

But if an assembly can’t be made, or one can’t escape, then

“the house of one is to him his castle and his defence, and where he properly ought to remain…a servant can beat one in defence of his master…a servant can slay one in saving the life of his master, if he [the master] cannot otherwise escape.”2

HOME IS WHERE THE HEART IS

When the home comes to be known as a place that offers comfort, solace, independence, privacy, and the legal right to harm – even kill – an intruder you deem threatening, it also becomes a place that excludes. The ‘head of the household’ can assert their superiority; especially when coupled with traditional gendered roles. It’s where phrases like, “Are you the man of the house?” or “Who wears the pants in this family, anyway?” serve to validate and perpetuate male superiority and dominance in the home. At its worst, can even lead to domestic violence.

What, then, does this say of homelessness? If Western social norms, legal text, and financial incentives favor home and property ownership, imagine what kind of insecurities or negative connotations come with being without one? Many fear the homeless, but the fears of the homeless – or nearly homeless – are surely greater.

And what about homeless people who call their city their ‘home’? Imagine living in a city your whole life, renting as an adult, maybe even saving to buy a house, when suddenly a rent increase pushes you out to live in your car, on the street, under a bridge, or in a park. These people have not left home, but are considered ‘homeless’. ‘Houseless’ is more accurate, but does little to ease the feelings of loss, anxiety, and pain that comes with losing a roof over your head and the status that comes with it.

If homes are a place of inclusion for the owner and its occupants, a place of’ belonging’, what places outside of the boundary of the home do we ‘belong’? We perceive our environment through the most intimate of senses; touching, tasting, hearing, smelling, and to the least intimate, seeing. But we are bounded in our ability to absorb and reason over the barrage of information our senses provide. We are thus influenced by our abilities and reasons for being in particular places.

These inputs form mental images that help navigate space, are shaped by perceptions, preconceived notions, and relationships with people and place. Each individual understands and relates to their environment in unique ways. Environments, territories, places, and the people in them, do not exist in some objective ideal but in a subjective reality informed by our senses, beliefs, and histories.

Humanistic geographer David Ley, who leveraged the work of the French geographer Vidal de le Blache, asserts that ‘home’ is a combination of the very real, regional physical environment with which we can see, touch, hear, and feel – our objective reality – and the social environment formed by the lives we lead – our subjective reality – which can be influenced by our imaginations and our emotions.3

Humanistic geography relates ‘home’ to a sense of ‘belonging.’ This sense or feeling exists at multiple scales from our body, abode, neighborhood, town, region, county, state, or country. We talk of ‘home towns’, ‘home field advantage’, or ‘hangin’ with my homey’s.’ And when we’re far away from them for a long time we often yearn to ‘go home.’ We become attached to these ‘homes’. They become a part of who we are – a slice of our identity and pride. The way we think of our ‘homes’ is how we would like others to think of us. There’s a word for this ‘belonging’ that combines the Greek words ‘love’ and ‘place’: topofilia.4

But this sense of ‘belonging’ is more than identifying with our physical surroundings. It’s more than the senses detect as you return ‘home’ from a long journey; it may be the smell of rich soil, the humidity enveloping your body, the cool mist absorbed by your thirsty pores, the arid sun radiating your closed eyes, or that songbird signing in the tree. ‘Belonging’ can also mean belonging to the people of that place – real or imagined.

These people and places with which we feel ‘belonging’, at scales ranging from our bodies to homes, neighborhoods to cities, or states to countries become defensible. We become territorial. This need and desire to defend ourselves, our people, and our place is an act of control that aims to exclude others.

Territories are defined by boundaries. Boundaries, when seen from the inside are protectors but from the side or the ‘others’ are rejecters. National borders, for example, are not natural and often have no physical demarcations at all. Nor are they fixed in space or time. These imaginary boundaries are created and maintained by various people over the course of history who make determinations on who is inside and outside the border. And it’s based on a this elusive notion of ‘belonging’. In the case of national borders, it’s based on a national identity – a ‘homeland’.

BORDER DISORDER

A nation-state is an idea that is grounded in a fabricated ideal created by a select group based on the identity they assigned to a particular set of people. This manufactured idea and it’s origins, like any idea, is contestable, changeable, and continually in flux. Like the borders themselves. To give the illusion of permanence to these unnatural homeland borders, and the national-identity they suggest, requires a constant propagation of ‘myths’ – propaganda. To reduce or eliminate contention of a fabricated national-identity, or the borders they represent, people need to be convinced these territories must be be defended. Just as they would their own body or home.

Geographer Stephen Daniels suggests that both these real physical geographies and perceived national identities are interdependent. He says,

“…national identities are ‘coordinated, often largely defined, by “legends and landscapes”, by stories of golden ages, enduring traditions, heroic deeds and dramatic destinies located in ancient or promised home-lands with hallowed sites and scenery’.”5

UCLA Geographer John Agnew calls this a “territorial trap”. He says that by “regarding states as fixed units of territorial sovereign space, unchanging through time; separating domestic (inside) from foreign (outside) political spaces; [and] treating the territorial state as a container of society”6 we are committing a conceptual error.

It is this very trap that Trump tapped to prop himself up as president. He would repeatedly say, “If you don’t have a border, you don’t have a country.” To make the invisible border visible, he focused on building a wall. He encouraged his disciples to chant, “Build the wall, build the wall.” Staged political performances at the border drew the attention of the world. While making the intangible tangible, he strengthened the territorial trap. He perpetuated the myth that this border represents a “fixed territorial sovereign space unchanging through time”.

But the United States didn’t even have a border patrol until Herbert Hoover in 1924. It too was largely a performance with the same racist goals as Trump – sweep those dirty, dusty Mexicans outside. That same meager border patrol of the 1920s remained meager until the 1990s. And remember, Texas, a state that shares a border with Mexico, was its own country, the Republic of Texas, under President Sam Houston for nearly a decade before the U.S. annexed them in 1845. There is nothing fixed or permanent about borders or territories.

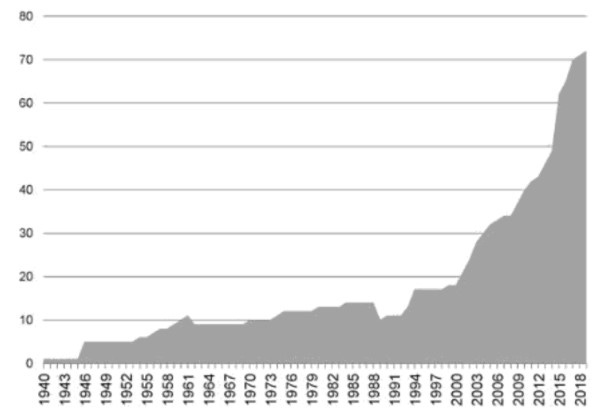

This fetishizing of territorial boundaries has fueled a rise in border walls over recent decades. Guggenheim Fellow and political geographer Reece Jones writes,

“Two thirds of the seventy border walls that exist today were built in the past twenty years by countries as diverse as Bangladesh, China, South Africa, and Norway.”7

In the 2020 book Borders and Border Walls, Élisabeth Vallet shows how border walls have gone from nearly zero in 1940 to over 72 in 2020. What’s more telling is 47% of those are built by democratic governments, 35% authoritarian, and 18% a hybrid of both. I’m assuming the U.S. is in the democratic bucket, but indeed may be slipping into hybrid.8

In a 2020 paper called Populism, Sovereigntism, and the Unlikely Re-Emergence of the Territorial Nation-State, British historian Aristotle Kallis writes that it leads to

“economic nationalism and an embrace of protectionism, political chauvinism, isolationism, reassertion of strict border controls, reversal of previous international commitments, and an expansive range of discriminatory measures targeting those excluded from the narrow definition of ‘the people’.”9

Reece Jones puts it like this,

“Since states the world over are threatened by the dawning of a global consciousness—a global awareness of economic, political, and environmental connections—states everywhere are responding with increasingly violent efforts to signify their control over their borders. Indeed, the border has become the location for the performance of the territorial sovereignty of the state, par excellence.”10

Populist, nationalist politicians and parties are behaving like a homeowner who’s convinced their home is soon to be invaded. The dust collecting around their ‘homeland’ are people who look different and share different beliefs and ideals. In America, Black and Indigenous scholars are surfacing alternative territorial and societal histories that intrude on traditional “legends and landscapes” many in this country believed to be fixed. These people are ensnared in a territorial trap, scared the rope is about to snap. So they build walls and political clout, they make calls to keep it all out.

But the dust they fear isn’t going away. Try as they may, global consciousness is here to stay. So they best remember what George Carlin had to say.

“Dusting is a good example of the futility of trying to put things right. As soon as you dust, the fact of your next dusting has already been established.”

People and Place: The Extraordinary Geographies of Everyday Life. Lewis Holloway, Phil Hubbard. 2001.

Word Histories. Pascal Tréguer.

Holloway, Hubbard. 2001.

Topophobia is the fear of place.

Holloway, Hubbard. 2001.

Dictionary of Human Geography. Alisdair Rogers , Noel Castree , and Rob Kitchin. 2013.

Locating the territoriality of territory in border studies. Anssi Paasi, Md Azmeary Ferdoush, Reece Jones, Alexander B. Murphy, John Agnew, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, Juliet J. Fall, Giada Peterle. 2022.

Borders and Border Walls In-Security, Symbolism, Vulnerabilities. Edited By Andréanne Bissonnette, Élisabeth Vallet. 2021.

Populism, Sovereigntism, and the Unlikely Re- Emergence of the Territorial Nation-State. Aristotle Kallis. 2018.

Paasi. 2022.