Hello Interactors,

The weight of winter up north can have its cozy comforts, but cold, damp, and dark can take a toll. We also continue to face a convergence of daunting global challenges — climate change, inequality, political instability, and health crises — each amplifying the other straining our ability to find meaningful and sustainable solutions. So much for ‘Happy Holidays’.

A recent article on avoiding despair1 turned to the concept of “tragic optimism.” This can sometimes be offered as a way to avoid our human tendency to seek “doom and gloom” while also not succumbing to “toxic positivity.” These topics struck me as a decent lens to kick off this winter’s focus: human behavior.

Let’s unpack the emotional geographies that shape us. How do spaces and norms influence how we feel, process, and express emotions?

SPACES, SMILES, AND SOCIAL SCRIPTS

When I was in seventh grade, I was the lead in our middle school musical, Bye Bye Birdy. It featured the song, Put on a Happy Face that employed this cheery, but pushy, line: “Spread sunshine, all over the place…just put on a happy face.”

Dick van Dyke played the starring role on Broadway from 1960-61 earning him an Tony award. He then appeared in the movie in 1963, launching him to stardom. In that role, many other roles, and in real life, he is a man who appears perpetually happy. Even now at age 98!

But under that smile, lurks a darker side. Soon after his early success, Van Dyke became an alcoholic. The alcohol may have helped him put on a happy face society expected, but it came at a price. This insistence on relentless optimism regardless of circumstances is called “toxic positivity” — and it’s more than a personal behavior. It reflects societal norms that prioritize surface-level harmony over emotional complexity. These norms shape how we navigate feelings and influence our individual well-being.

But shared spaces, like our workplaces or homes also influence these emotional dynamics. Have you ever walked into a place knowing how you were expected to act? At work, you might slap on a smile and say “I’m fine” even when you’re not. At home, you might feel the pressure to play the part of the cheerful parent, partner, or roommate. These emotional scripts don’t come out of nowhere — they’re baked into our cultural expectations about what different spaces are “for”.

Geographer Yi-Fu Tuan explains that spaces acquire “moral properties” through societal norms, values, and cultural narratives. Workplaces, seen as sites of productivity, often suppress emotions like frustration, while homes, idealized as places of comfort, pressure individuals to adopt roles like nurturing parent or cheerful partner. These norms shape how people are expected to behave and feel within these spaces.2

America itself, as a cultural and geographic entity, carries its own "moral properties." These are reinforced by media narratives that frame the nation as a land of optimism, resilience, and emotional stability, projecting these expectations onto its citizens and then exported to the world to consume.

Take one of the most-watched television programs in America from 1962 to 1992, Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show. His late-night TV persona was examined in a recent New York Times piece by Jason Zinoman. He described Carson as America’s calm, neutral host, soothing the nation with his polite humor. He wasn’t just a TV personality; he was part of a larger cultural push for emotional stability, especially during times of uncertainty. His show became a space where people could escape the messiness of real emotions.3

But these expectations aren’t just about comfort — they’re about control. By promoting harmony and cheer, society nudges us toward emotional conformity, discouraging anything that might feel too “messy” or unpredictable.

This pressure doesn’t fall on everyone equally. Women often bear the brunt of emotional labor, expected to keep things “pleasant” for others. Cultural geographer Linda McDowell highlights how professional women are frequently required to maintain an upbeat attitude at work, regardless of personal circumstances. This expectation extends beyond the workplace, shaping how women are perceived and allowed to express themselves.4

On The Tonight Show, Joan Rivers, a trailblazing comedian, faced this constraint. Despite her sharp, satirical wit, Rivers was often limited to lighthearted banter and self-deprecating humor to align with Johnny Carson’s carefully neutral persona. Similarly, Carol Wayne, as the flirtatious “Matinee Lady,” reinforced the idea that women on the show were there to amuse or adorn, not disrupt. These portrayals reflected societal norms that confined women to roles as caretakers or decorative figures, both publicly and privately.

SUPPRESSING SORROW WITH A SMILE SUCKS

Putting on a happy face might seem harmless, but it can take a toll. When we suppress feelings like sadness, frustration, or anger, they don’t just disappear — they build up, creating stress. They can even impact our physical health. Neuroscientists have shown that suppressing emotions can increase activity in the brain’s fear center (the amygdala) while dampening the rational, problem-solving parts (like the prefrontal cortex). Basically, pretending you’re okay when you’re not can mess with your head and your body.

James J. Gross, a psychologist and leading researcher in emotion regulation, has shown that suppressing emotions can heighten stress levels, activate the brain’s fear center (the amygdala), and disrupt cognitive processes critical for resilience and problem-solving.5 Recent brain imaging studies by Wang and Zhang (2023) support this, demonstrating that expressive suppression, where feelings are actively withheld, triggers heightened amygdala activity and diminished prefrontal regulation.6 These findings highlight the significant physiological toll of emotional suppression, further validating Gross's work.

Viktor Frankl, a Holocaust survivor and existential psychologist, offers a valuable framework for regulating these emotions with his concept of “tragic optimism.” Frankl introduced tragic heroism in his 1978 book, The Unheard Cry for Meaning, drawing on the existential and Greek tragic tradition of resilience in the face of suffering. He later expanded this with tragic optimism in a 1984 essay, emphasizing hope and meaning-making even amidst life’s inevitable hardships.7 8

Drawing on his experiences from the Holocaust, he explores the human ability to confront inevitable suffering while maintaining hope and finding meaning. For Frankl, this approach was not about denying pain but about embracing life’s full spectrum — its joys and its tragedies — as integral to human existence.

But his view of suffering has been criticized as overly universal and idealistic, assuming that all individuals can derive purpose from adversity.9 His emphasis on personal responsibility may inadvertently shift blame onto individuals for not overcoming circumstances beyond their control. Constant pressure by systemic oppression can exist even in a society that claims to be free.

Migrant women in caregiving roles, as McDowell highlights, often lack the freedom to balance suffering and hope on their own terms. Instead, they are required to project resilience and positivity, even under exploitative conditions, effectively masking systemic inequities.10

Similarly, Joan Rivers and Carol Wayne were cast into narrow roles that demanded cheerfulness, ensuring they complemented rather than challenged societal norms. These portrayals reflected the broader expectation that women embody emotional steadiness, regardless of personal circumstances.

Frankl’s insights remind us that the ability to engage with hardship meaningfully is a privilege that societal expectations often deny to those at the margins. Understanding the toll of suppression and the uneven distribution of emotional freedom is crucial in challenging the norms that perpetuate these dynamics.

COMBATING CONFORMITY WITH COMMUNITY

Thankfully, norms aren’t set in stone — they can be, and have been, resisted and redefined. Sara Ahmed, a feminist scholar, critiques what she calls the “happiness duty.” She shows how this duty pressures marginalized groups to appear cheerful, suppressing feelings like anger or pain to uphold the status quo.11 Movements like Black Lives Matter reject this demand, openly expressing grief and frustration to confront systemic injustice. Through “collective effervescence”, as sociologist Émile Durkheim describes, collective emotions in protests turn individual pain into powerful demands for change. Ahmed and Durkheim offer examples of how breaking free from the pressure to "stay positive" transforms emotions into tools for meaningful resistance.

But even this kind of resistance can make those in power uncomfortable, so they demand order, calm, and happiness. When collective effervescence calls people to, as Public Enemy’s song decries, ‘fight the powers that be’, another collective encourages everyone to spread ‘sunshine all over the place, and just put on a happy face.’

But in the face of this “toxic positivity” that Public Enemy mocks as, “'People, people we are the same'”, they respond ‘No, we're not the same / 'Cause we don't know the game’. They can’t justify putting on a happy face when most of America refuses to wrestle with poverty and race. Summoning an inner Johnny Carson can be seen by some as not a neutral, but as just another way to paternally placate — to pat down incivility. It can be seen more like Jack Nicholson’s infamous “Here’s Johnny!” in The Shining — a menacing veneer of cheer masking a deep, dark, and discomforting societal reality.

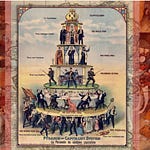

Ananya Roy, a geographer and urban theorist, takes a hard look at this in her work on the “rescue industry.” In Poverty Capital, she critiques how even well-intentioned aid organizations often portray marginalized communities as helpless and in need of saving, while ignoring the structural problems that keep them oppressed.12 These narratives don’t just undermine real change — they also place emotional expectations on those being "rescued." They demand gratitude and resilience while leaving the bigger systems of inequality intact.

Roy’s work shows how this approach reflects a long history of paternalism and American exceptionalism, where those in power maintain control by shaping how others should act and feel.

Geography plays a big part in how these expectations are enforced. Relief camps, aid programs, and even microfinance initiatives often create spaces where people are expected to behave a certain way — thankful, hopeful, and compliant. In the U.S., similar patterns show up in low-income neighborhoods, where anger or frustration is often punished, reinforcing norms that demand harmony and silence over real emotional expression.

If we want to resist these dynamics, we need to rethink the spaces where care and support happen. Instead of controlling emotions or enforcing positivity, these spaces should allow for shared agency and the full range of human feelings. By rejecting savior narratives and making room for emotions like grief and anger, communities can start to challenge the systems that hold them back and move toward real change.

From Johnny Carson’s seemingly cheerful neutrality to the "happiness duty" imposed on marginalized groups, societal norms can slowly prioritize control over connection, faux harmony over brutal honesty. But resistance is possible.

Movements like Black Lives Matter, the Women's March, Chile's protests for constitutional reform, and Hong Kong’s pro-democracy demonstrations highlight how group effervescence can channel collective emotions into impactful resistance. However, these movements also reveal the limits of protest alone in achieving enduring change. Systemic barriers to change require sustained efforts beyond the initial wave of mobilization.

As Ananya Roy reminds us, breaking free from narratives of saviorism and exceptionalism requires not just challenging these norms but rethinking the spaces where they take root. How can we build geographies of care that empower, rather than constrain? Perhaps the answer lies in acknowledging that resistance begins with feeling — and making space for emotions, no matter how “messy” they might seem.

Stulberg, B. (2024). How Not to Fall Into Despair. The New York Times.

Tuan, Y.-F. (1977). Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press.

Zinoman, J. (2024). Johnny Carson and the Fantasy of America. The New York Times.

McDowell, L. (1997). Capital Culture: Gender at Work in the City. Wiley.

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion Regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social Consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291.

Wang, Y., & Zhang, D. (2023). Cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression evoke distinct neural connections during interpersonal emotion regulation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 43(49), 8456–8471.

Frankl, V. E. (1978). The unheard cry for meaning: Psychotherapy and humanism. Simon & Schuster.

Frankl, V. E. (1984). Man’s search for meaning: Revised and updated edition. Pocket Books.

Ehrenreich, B. (2009). Bright-sided: How positive thinking is undermining America. Metropolitan Books.

McDowell, L. (2009). Hard Labour: The Forgotten Voices of Migrant Workers. Routledge.

Ahmed, S. (2010). The Promise of Happiness. Duke University Press.

Roy, A. (2010). Poverty Capital: Microfinance and the Making of Development. Routledge.