Hello Interactors,

As the holiday season calls on us to shop online, it’s worth considering the cost. I’m not talking about the price of the item your mouse is hovering over, but the hidden cost of getting it delivered to your doorstep.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

GETTING HIP TO A TIMELY TIP ON A CALIFORNIA TRIP

“I think you’re transporting drugs”, my cousin said casually. “Why else would they send a 20 year old kid to New Jersey from L.A. just to drive an old station wagon across the country?” “You’re the perfect foil…a 20 year old blond kid from Iowa just doing his job…no cop would ever think to search for drugs.”

It was on my mind the whole trip. Especially when I was pulled over in Nebraska for speeding. A portly County Mounty waddled his way to the car as I deftly stashed the radar detector under my seat. I watched him in my side mirror as he put on his hat while approaching the car. Cold winter wind rushed in as I rolled the window down and greeted him with the best rural “howdy” I could muster. I then asked him how fast I was going. He pulled his glasses down over his nose, looked me straight in the eye and said, “I don’t know, son, but it took me 10 minutes to catch up to you.”

He was indeed curious about the New Jersey plates and why I was headed to California, but he let me go with a warning. “Take it slow, son, I’m sure those folks out West want to see you make it ok.”

By the time I got to the California border, I was ready to be done. I decided to take the southern route into L.A. – the famed Route 66. I had hit a lot of snow in Colorado and was eager for sunny, dry roads. But that would have to wait. A massive ice storm met me in the high desert town of Victorville, California. I was barely able to find a place to stay for the night as the freeway was lined with cars in the ditch.

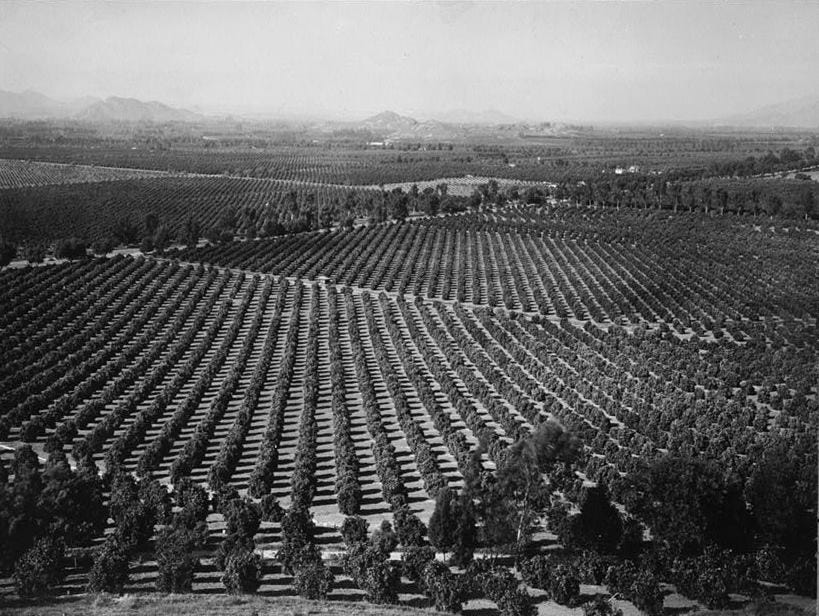

The next morning the roads were bare and wet as I headed west through the pass dividing the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountains and into the vast San Bernardino valley. It was named by Spanish colonizers who took the same route in the late 1700s, then more Europeans a century later, and fellow Iowans soon after that. This valley was once home to sprawling citrus groves that attracted winter weary farmers from the Midwest. It was still agricultural when I was inching my way toward L.A. in 1985 in a blue Oldsmobile station wagon – a suspected innocent drug smuggler.

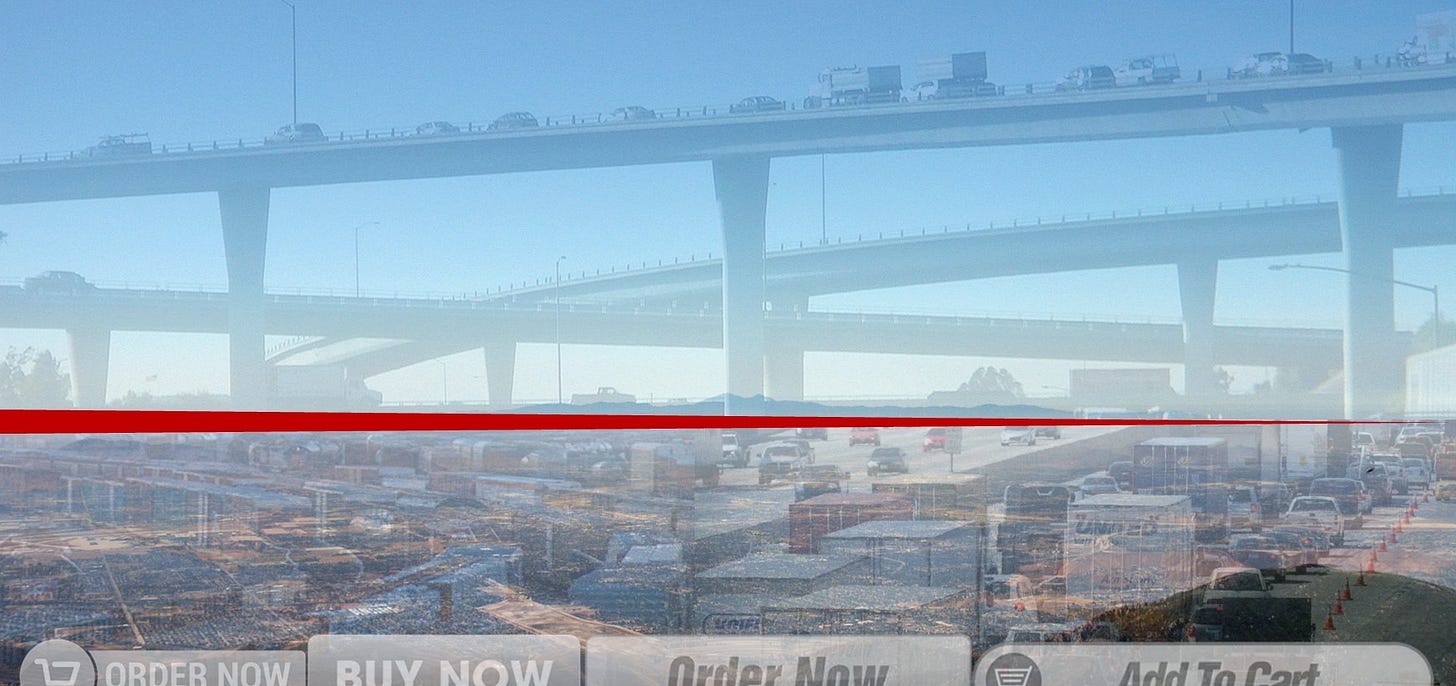

And then just last week there I was, over 30 years later, plodding my way toward L.A. down the same Interstate 10. My family and I took a trip to Southern California to visit schools for my son. A lot has changed. They paved paradise and put up parking lots, warehouses, and sprawling housing developments too. The freeways were crammed with semi-trucks as commuters blinkered their way through the lanes. They were competing for space in their hour-plus long trek to jobs in the L.A. basin.

It’s a long commute to and from what is known as the Inland Empire, but the average selling price of a home is $482,000. That’s nearly half of what you’d pay in Los Angeles ($841,000), further south in Orange county ($983,000), or San Diego ($802,000).1

While four hundred grand is relatively low for Southern California, prices are climbing. The average price is already above what it was before the financial collapse of 2008. That’s when average single family home prices in the Inland Empire plummeted to under $200,000. The region was home to some of the worst foreclosure stories in the country. At one point, one in five homes in the area were in foreclosure. People were literally walking away from their homes. Even though housing is booming again, inventory is actually lower than it was before the collapse.

Wall Street backed firms like the Blackstone Group, the Lewis Group, and Oak Tree Capital Management swooped in and bought large swaths of foreclosed homes.2 They’ve been renting them to those who can’t afford to buy until the price of the home reaches a level they feel they can best profit by selling. Buy low, sell high and wish the struggling family good bye.

(Incidentally, the founder of Blackstone, Stephen Schwarzman, who is worth around $21 billion, was one of a handful of billionaires who continued to support Trump financially after the raid he incited on the capital. And when the Obama administration suggested Wall Street fund managers like Schwarzman pay at least as much in taxes on earned interest as ordinary wage earners, Schwarzman said Obama was waging war on the wealthy and added, “It’s like when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939.” What an odd and insensitive comparison for a Jewish man to make. But, Trump has a way of attracting odd and insensitive people.)

As billionaire backed firms competed for foreclosed housing stocks, there was no chance a single individual seeking to buy a home could get in on the competition. One man in Rancho Cucamonga bid on over 200 houses but failed on all accounts. 3And while these outside firms were scooping up homes at $200,000 a pop as late as 2012, new housing construction was selling at $300,000 to $800,000. While this was a small fraction of the total, it incented even more developers to build more expensive homes which continue to drive up prices across the region.

WORLD HYPOXIC CENTER

But the 2008 housing crisis wasn’t the first to hit the Inland Empire. Trouble was brewing even as I lumbered through the valley in the mid 1980s in that New Jersey station wagon. In 1978 California passed Proposition 13 which altered how property taxes were calculated. The law was intended to reduce property tax burdens on residents already being forced to the more affordable periphery of desirable urban centers across L.A. The Inland Empire absorbed many of those people throughout the 80s, 90s, and 2000s – and continues to attract more to this day.

Proposition 13 also changed the financial dynamics between state, regional, and local economies as local tax revenues plummeted. Local governments had to find new sources of revenue resulting in these three primary (and familiar) outcomes;

“1. the appearance of auto malls and big-box retail stores, and the disappearance of ‘mom and pop’ shops in virtually every community in the region;

2. new relationship between land developers and municipal authorities;

3. the creation of private/public development projects as potential revenue generators.”4

It didn’t help when a steel factory shut down in 1983 eliminating 10,000 jobs. Then, in 1991, as the Cold War threats diminished, George H. W. Bush shut down the Norton Air Force base and closed a nearby missile factory. Then, in 1993, the March Air Force base was also trimmed. Over 30,000 jobs were lost accounting for nearly seven percent of the area’s population.

By the mid 1990s multi-national corporations were moving manufacturing hubs and jobs overseas. As trade imbalances mounted container ships began piling up at the Long Beach Port due south of the Inland Empire. Portside storage facilities were overwhelmed and distributors began looking to the Inland Empire for land to build new, large, modern distribution centers.

Within a decade vineyards and dairy farms were replaced with warehouses. One month residents were driving by signs advertising fresh fruit and then next a block long gray box with an Amazon sign bolted to the wall. Sketchers has a single facility stretching 1.8 million square feet and hopes to expand their footprint as part of an area wide 41.6 million square feet warehouse expansion.5 By the end of 2013 the Inland Empire had become the Warehouse Empire of the nation accounting for 1.6 billion square feet of distribution, logistics, and warehouse facilities.

Forty five percent of the nation’s imports are trained, trucked, or flown into the Inland Empire, unpacked, sorted, and reloaded onto trains, trucks, and planes that then fan out again across the nation. It’s like a logistics heart that pulses goods purchased with a single click through the veins and arteries of the nation’s transportation infrastructure.

The city of Moreno Valley is building what they call the World Logistic Center. It’s a 41.6 million square foot $3 billion expanse that will feature a 2,600 acre corporate campus. While they claim it will be one of the most sustainable corporate campuses in the nation, the South Coast Air Quality District estimates the project will add an additional 30,000 heavy-duty trucks to area roads per day.6 That’s nothing but dollar signs for some, but nothing but trouble for most.

Heavy-duty diesel trucks emit 24 times more fine particulate matter than regular gasoline engines.7 These are the chemical compounds that are so small they easily seep into the lungs and pollute blood streams. The State of California and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have identified more than 40 different toxic pollutants in diesel emissions.

“In 2003, the Riverside and San Bernardino counties ranked first and second, respectively, in the nation for total particulate pollution.”8

Between 2000-2002 Riverside’s particulate matter concentrations were 1.75 times the federal limit and more than twice the state’s standard.

One 2007 study conservatively estimated that the “logistics industry expansion will cause 32-64 cases of excess mortality and morbidity valued at $247-455 million per year.”9 Those living closer to the freeways will be effected more. And because housing is cheapest along the noisiest and most polluted roadways, those most impacted will be those most vulnerable physically and financially – which historically are people of color and the elderly.

PROPOSITION UNSEEN

The Inland Empire is a regional microcosm of economic geography. It’s part of a global experiment – a worldwide economic capitalistic petri dish – that has been festering and bubbling at different scales since the 1970s. As residents were pushed out of settled areas in the L.A. basin due to rising property values, the Inland Empire became a target for sprawl. The passing of Proposition 13 cut funding for public health, education, and infrastructure forcing local governments to pursue public/private partnerships.

Proposition 13 also included special provisions for commercial development, attracting opportunistic capitalists and politicians. To this day, city and county government officials across the Inland Empire continue to be investigated, charged, and tried for bribery, corruption, attempts to destroy documents, and guilty pleas.10 While the gentrification attracts jobs and provides much needed housing and flows money through the region, it also increases commute distances, clogs roads, and contributes to some of the worst air pollution in the country.

That flow of capital into the Inland Empire is coming from state and national economic policies that started in the 1970s. Seeing an end to the post-war growth of the 1950s and 60s, the United States and their allies instituted financial deregulation that reoriented their capitalist economies. Globalization was on the rise at the same time the U.S. allowed for more foreign investment on American soil.

When I was living in L.A. in the 80s, it was private and commercial Japanese investors grabbing up property and high rises in L.A. Now the top three foreign investors come from Canada, Mexico, and China. And they’re largely interested in suburban areas like the Inland Empire.

The very financial regulation that created the necessary funds to build the seaports, airports, railways, and freeways that provide our economy’s circulatory system have been diminished by both parties over the last 50 years. The 1978 California Proposition 13 was a warm up act for Reagan’s failed tax-cut, trickle down theories he claimed would bring prosperity to every American. Every president since has been promising as much yet income disparities continue to grow. Jeff Bezos’ net worth has grown $65 billion since the start of the pandemic. Meanwhile, even a hint of inflation threatens to push millions more into poverty and thousands to live in their cars or on the streets.

It should be noted that the logistics business in the Inland Empire would likely not exist if it weren’t for a federally funded air force base that has since been converted to air cargo airports where streams of cargo planes land 24/7. Not to mention the federal and state funded freeways crisscrossing the valley that private heavy-duty trucks use and abuse with little to no restrictions. Trucks that are driven by drivers who continually fight for their right to organize for fair wages and healthcare. And let’s not forget the federally funded internet that makes it all too easy to click a ‘buy’ button and have a package magically arrive the next day…most likely through a sprawling warehouse in the Inland Empire.

Globalization – and the functional regulation of the world economy by select countries – has complicated the flow of capital through regions like the Inland Empire. It’s left small town governments stretched and starving for funds. They’re stuck begging for crumbs from money-rich corporations in exchange for favors. It’s led to criminal activity among conspiring opportunists – some of whom are simply trying to secure funds for schools.

I doubt I was trafficking cocaine. I was working for one of L.A.’s oldest company’s, Platt Music Corporation. They started out selling sheet music but had morphed into a consumer electronics distributor – also known as a middle-man. If you bought a TV in a California department store in the 80s, it likely went through Platt. They had just gone public a year before I started running errands for them across the far reaches of L.A. – and the country. But then big-box stores like Circuit City and Best Buy appeared and increased competition for consumer electronics. Soon department stores were forced to negotiate their own prices directly with manufacturers. Platt folded in 1987 after 82 years of doing business in L.A. Another ‘mom and pop’ shop gone. Capitalism eating itself.

CAPITAL ARREST

Geographer David Harvey put it best when he said, “Capitalists behave like capitalists wherever they are. They pursue the expansion of value through exploitation without regard to the social consequences.”11 And the Inland Empire, a struggling locus to distribute and focus the country’s goods, is a prime example that leads Harvey to conclude, “The accumulation of capital and misery go hand in hand, concentrated in space.”12

Many economic geographers contend that both perceived and real economic and social crisis are necessary for capitalism to sustain itself. Circuits of capital flowing inside the Inland Empire interact with circuits flowing outside in ways that transform the culture and shape of it’s cities. The constant expanding and contracting creates inequities and uneven development that capitalists then exploit. We often think of capitalism as a constant that can be universally applied, but in reality it thrives off of localized geographic and economic upheaval and repair – starve one area to reduce it’s value, buy low; boost investments through private capital and governmental lubricants, sell high; then seek or create the next devalued area.

This process is sold to us as job creation. It can, but often at the expense of jobs elsewhere. Production of goods and services is a social process while the ownership of production, and the profits that come with it, are largely privately held. Unless there are laws in place to distribute portions of the wealth accumulation in support of the social process of production, streets crumble, cities stumble, and angry residents rumble. We’re witnessing how the concentrated accumulation of capital and misery indeed go hand in hand.

We humans are really good at calculating the price of convenience, but are terrible at measuring the cost. For example, privileged car owners happily jump in the driver’s seat knowing how comfortable and convenient it is. But few stop to consider how much space a car takes up on the road, how much their tire dust is floating into the mouths of fish, or how many toxic exhaust chemicals are sucked into the lungs of that kid standing on the corner.

And how many of us hesitate to click ‘buy’ knowing how nice it is to have a package delivered to our doorstep in 24 hours or less? We don’t consider the additional 30,000 heavy-duty trucks that will rumble down the local roads and freeways of the Inland Empire. Or the how local warehouse workers will make ends meet when Amazon replaces them with robots. Or what about the critters living in the foothills of the valley?

Someone is thinking of them. In 2020 the Friends of the Northern San Jacinto Valley, sued Moreno Valley over further expansion of their Global Logistics Center into sensitive areas. They settled just a few weeks ago. Six hundred acres will be added to the endangered-species reserve system in exchange for enough land to build the equivalent of 40 shopping malls worth of warehouse space. The Inland Empire really is the Warehouse Empire.

Maybe it’s time we pull consumerism over and slip on our hat as we saunter up to the speeding capitalist. And when they roll their window down asking how much damage they’ve done, we peer over our glasses and earnestly say, “I don’t know, son, but it’ll take generations to fix it.”

UC Riverside. 12th Annual Inland Empire Economic Forecast Conference. 2021.

Thomas Patterson. From Acorns to Warehouses. Historical Political Economy of Southern California’s Inland Empire. 2015.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Warehouses, Trucks, and Pm 2.5: Human Health and Logistics Industry Growth in the Eastern Inland Empire. Randall A. Bluffstone and Brad Ouderkirk. 2007.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Thomas Patterson. From Acorns to Warehouses. Historical Political Economy of Southern California’s Inland Empire. 2015.

David Harvey. The Limits to Capital. 2006

Ibid.