Hello Interactors,

On the day before many around the world pull out ‘T’was the Night Before Christmas’ to read to their kids, maybe drop a little context to the origins of this tale. This is an excerpt from a longer post I did in 2021 on Black Friday.

It touches on how the rising wealth in New York leading up to 1900 brought about shifts in attitudes around how the powerful elite should deal with ‘the masses’ of poor, and increasingly urban, immigrants. Included are themes emerging today like immigration, laws outlawing voting to non-property owners, and even calls for an end to democracy.

‘T’was the Night Before Christmas’ was intended for the elite literate ruling class. It can be interpreted as a nostalgic romantic tale about how Christmas should be less about sharing with ‘the unruly masses’ — communally seeking good tidings — and more about barricading private homes from potential invasion and keeping your wealth to yourself. It’s a fantasy about letting a poor, kind peddler in a red tattered coat labor to bring gifts to affluent kids, quietly and calmly through the chimney of a fancy New York apartment.

Merry Christmas!

CLOTHES WERE ALL TARNISHED WITH ASHES AND SOOT

But the dawn of a new century, and the industrial age, brought a shift in attitudes around Christmas. The elite, like in centuries past, distanced themselves from the occasion. As urban cities grew and jobs shifted from the farm to the factory, winter brought new dynamics to the onset of the season. Some factories closed in the cold months as did shipyards along frozen waters.

This brought unemployment and idle time to laborers. Whereas historically wealthy farm owners were willing to amuse the working class in a societal roll reversal – through transient and theatrical wassailing – the urban elite power structures were unwilling to participate. But it didn’t stop the working class from venting.

The once faint mockery of their employers – imbued with subtle hints of revenge should they not offer them gifts, food, or alcohol – turned fierce and riotous in the 1800s. Papers in both England and the United States barely mention Christmas at all between 1800 and 1820. But that was about to change.

In the first decade of 1800, one of New York’s most influential men, John Pintard, became particularly peeved by the seasonal banditti. He reminisced on ‘better days’ when the rich and the poor got drunk together. And while he wished his wealthy friends reveled more among themselves, he grew concerned that “the beastly vice of drunkenness among the lower laboring classes is growing to a frightful excess…”

And in a familiar tone, echoed to this day by many, he feared “thefts, incendiaries, and murders—which prevail—all arise from this source.” Which is why he helped create the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism. This was an organization that sought to curb money directed at care for the poor, but to also stop them from begging and drinking. The white elite ruling class of the 1820s –- as well as many in the 2020s – complained of what one New York paper described as, “[t]he assembling of Negroes, servants, boys and other disorderly persons, in noisy companies in the streets, where they spend the time in gaming, drunkenness, quarreling, swearing, etc., to the great disturbance of the neighborhood.”

Pintard was also hopelessly nostalgic. He founded the New York Historical Society in 1804 and was instrumental in establishing Washington’s Birthday, the Fourth of July, and Columbus Day as national holidays. Pintard also introduced America’s icon of nostalgia, Santa Claus. Seeking a patron saint for the New York Historical Society, and for all of New York City, he commissioned an illustration to be painted of St. Nicholas giving presents to children. While the icon was not intended to be seasonal, it was nonetheless printed on December 6th, St. Nicholas Day, in 1810.

He pined for the days when the rich and powerful could rule over what was becoming a burgeoning working class. In 1822, as New York had just passed a law allowing non-property owners to vote, Pintard wrote to his daughter,

“All power is to be given, by the right of universal suffrage, to a mass of people, especially in this city, which has no stake in society. It is easier to raise a mob than to quell it, and we shall hereafter be governed by rank democracy.… Alas that the proud state of New York should be engulfed in the abyss of ruin.”

WHAT TO MY WONDERING EYES SHOULD APPEAR

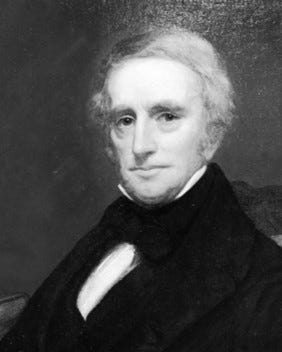

1822 was also the year his friend, and wealthy land owner, Clement Clark Moore, wrote what was to become the most influential Christmas poem ever: “A Visit from St. Nicholas” or as it is known today, “T’was The Night Before Christmas.”

This single poem, written for the elite upper class, encapsulates the nostalgia of wassailing Pintard and his friends pined for, while self-indulgently feeling good about themselves for ‘giving to the needy.’ Moore did this by substituting the unruly lower working class, begging for gifts from their master, with children expecting presents on Christmas morning.

He kept the gift giving mysticism of the centuries old St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, but removed the judgmental elements of a Bishop who may make them feel guilty for maintaining class divide by making him “merry”, “droll”, “rosy”, and “plump.” He also made him a lower class “peddler”. And while Santa made a loud noise “on the lawn” with a “clatter”, just as a lower class wassailer would have, he was but a small and unthreatening “right jolly old elf” who kindly left toys he had labored over for the children.

And he asked nothing in return. With a “wink of his eye” and a “finger aside his nose” (a gesture meaning “just between you and me”) Moore gave the privileged class, who were fearful of home invasions at Christmas time, assurance they “had nothing to dread.” All they needed to do, was keep their wealth within the family and buy their kids and friends gifts at Christmas time. Forget the poor, they thought, they’re as hopeless as democracy.

The vision and version of Christmas and Santa Claus that Moore provided his haughty affluent peers, in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, was soon to be read by a growing middle class and an increasingly literate lower class. That’s as true then as it is today.

And while Moore was a country squire who never worked a day in his life, and hated the gridding up of property in a growing New York City, he grew to love the money he earned selling off family property he inherited. Geographer Simeon DeWitt was chopping Manhattan into a Roman style grid to make room for a population that grew from 33,000 in 1790 to nearly 200,000 by the time Moore’s poem was written in 1822. He even included a chimney in his poem for Santa to climb down as a way for city folk to better relate to a scene he’d rather have happened in his bucolic hills of a New York of yore – an area today we call Chelsea.

Reference:

The Battle for Christmas. A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday. Stephen Nissenbaum. 1997