Hello Interactors,

We often think of the economy as a fixed, objective force, separate from who we are. But what if it actually shapes our identities? Like a DJ mixing a set, economics amplifies certain behaviors and silences others. I saw this firsthand last summer when Calvin Harris performed live in Scotland, dynamically controlling thousands of people with a turn of a dial or push of a button…on tracks he’d already mixed in the studio!

Brett Scott, in his recent Substack Remastering Capitalism, uses this music mixing metaphor to show how human nature is molded — elevated or suppressed — by economic systems. His insights remind me of social constructionism, which reveals that what we see as “natural” is often constructed by institutions, including the economy. Our many identities aren’t just reacting to the system — they are being shaped by it.

But what if Homo Economicus, the rational, self-interested individual, isn’t who we truly or solely are? What if these systems are muting our most moral and communal parts? With my last three posts on economics in mind, let’s explore how economics and geography construct — and limit — who we become.

MARKETS MOLDING MINDS

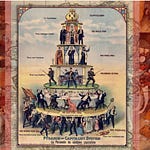

At the heart of social constructionism is the idea that reality isn’t something we passively experience — it’s something actively constructed through our social interactions, power dynamics, and the institutions that shape our lives. One of the most powerful institutions in modern society is the economy, which shapes not just markets but the very way we see ourselves and our place in the world. And, as with all social constructs, it is influenced by those who hold power.

In Econ 101, we’re introduced to Homo Economicus, the rational, self-interested individual who makes perfectly reasoned decisions geared toward maximizing utility without emotional interference. Think Spock from Star Trek. This figure is more than a character or abstract concept; it reflects the values that the market rewards and those in power promote. In environments dominated by capitalist systems — corporate boardrooms, stock exchanges, financial districts — the behavior of Homo Economicus is not just encouraged, it’s essential for success. These spaces reinforce particular versions of selves, constructed by the systems that surround them.

Critical geographer David Harvey emphasizes how geography and power intersect, asking us to

“Imagine, for example, the absolute space of an affluent gated community on the New Jersey shore. Some of the inhabitants move in relative space on a daily basis into and out of the financial district of Manhattan where they set in motion movements of credit and investment moneys that affect social life across the globe...”1

These elites embody Homo Economicus and reinforce the power dynamics of capitalism, constructing an economic landscape where rational self-interest reigns supreme.

But Homo Economicus is not an innate human identity. Like the concept of the “divinely appointed king” in medieval Europe, it is constructed by the economic and social systems around us. Modern capitalism creates and rewards this notion of the self. But this doesn’t mean we’re trapped in this role — other tracks of human nature are waiting to be heard. The question is, can we turn up the volume on those other selves?

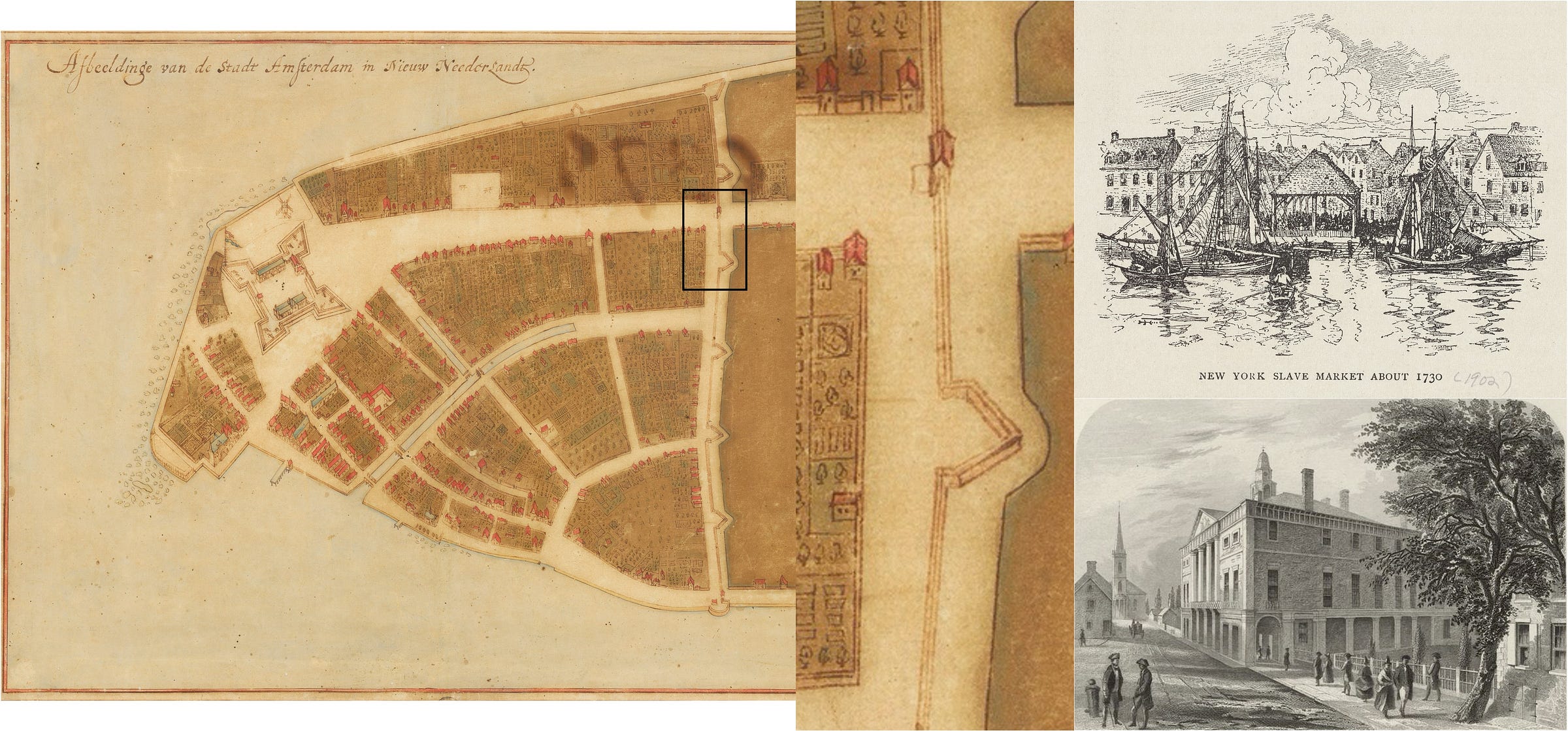

MAPPING MONEY’S MIGHT

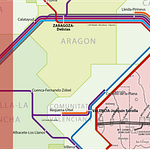

The dominance of Homo Economicus is not just theoretical — it plays out in real, physical spaces. Economic geography shows us how capitalism manifests in cities, financial hubs, and industrial centers, creating environments that reward certain behaviors while suppressing others. As Doreen Massey, a feminist geographer, notes, social relations are constructed across all spatial scales — from global finance to local communities — and these spaces, in turn, construct us. She writes,

“’The spatial’ then…can be seen as constructed out of the multiplicity of social relations across all spatial scales, from the global reach of finance and telecommunications, through the geography of the tentacles of national political power, to the social relations within the town, the settlement, the household and the workplace.”2

Having recently returned from New York and London last summer, I was surrounded by buildings and infrastructure designed to facilitate rapid decision-making and profit maximization. These financial districts are the birthplace of Homo Economicus, where competition, efficiency, and rationality are not only celebrated but engrained in the fabric of the city. But these aren’t just neutral places where economic transactions happen — they were actively shaped by human identities to shape other human identities, constructing versions of selves.

Yet, capitalism’s steady beat doesn’t stop at the thumping urban centers. It ripples outward, reshaping rural areas, natural landscapes, and global trade routes. In these spaces, a different identity might have flourished. For example, where I grew up in Iowa, rural areas are shaped by industrial agriculture where economic pressures push farmers to adopt monoculture practices, prioritizing profit over sustainability.

My father worked for farm equipment maker, Massey Ferguson in the 1970s and 80s where the company had to respond to John Deere’s introduction of industrial-sized articulated tractors sold to increasingly dominant large-scale farmers. Here, the track of Homo Ecologicus — the part of us that values balance and environmental stewardship — was quieted. Meanwhile, the relentless beat of industrial capitalism continues to drown it out.

However, these tracks aren’t erased. In more peripheral spaces — rural farms, local markets, and environmental movements — Homo Ecologicus still survives, embodying a different approach to the world, one that capitalism often suppresses.

A 2023 study showed that if 25% of institutional buyers sourced fresh food from local farms, it could generate an $800 million impact on Iowa's economy, supporting over 4,200 mid-sized farms and creating numerous agricultural jobs. In 2024 alone, Organic Valley, a cooperative that supports organic farmers, brought 40 new family farms in just the first four months of the year and was expected to add 70 more by year-end.3

The geography of capitalism constructs these different forms of capitalism and the human identities behind them. Where we live and work reminds us that we are shaped by the spaces we occupy. Our identities are far from static — they are deeply influenced by the economic forces, choices, and physical landscapes we inhabit and navigate — the Interplace, if you will, the interaction of people and place.

INDUSTRY INFLUENCED IDENTITIES

Although capitalism has amplified Homo Economicus in both urban and rural spaces, other aspects of human nature persist. Social constructionism teaches us that while dominant systems shape our identities, they can also be resisted. And in moments of rebellion or creativity, tracks like Homo Ecologicus and Homo Absurdum emerge, reminding us of the full spectrum of the human experience.

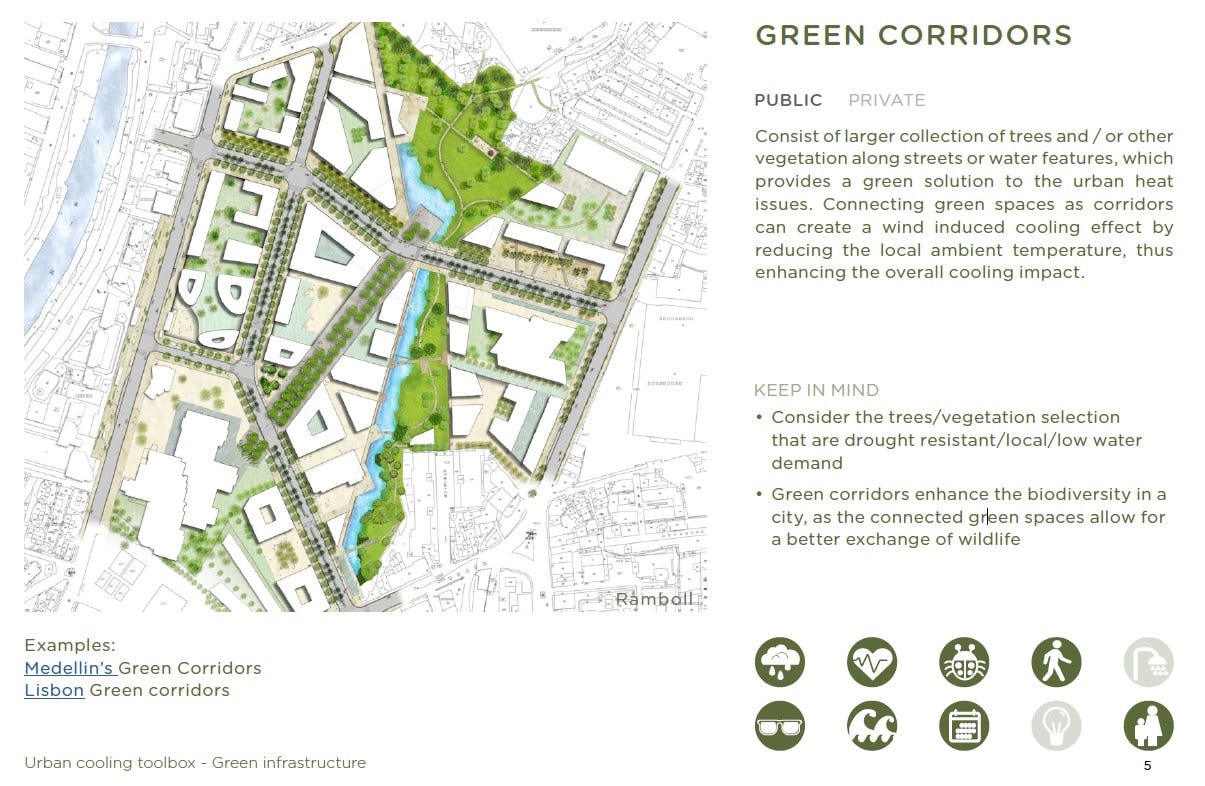

Homo Ecologicus embodies our connection to nature and the desire for harmony with the environment. In communities focused on re-greening — whether through small urban efforts, rural sustainability, or the traditional ecological practices of the Coast Salish, which I’ve explored previously — these identities resurface. The Coast Salish, like many Indigenous cultures, emphasize balance and stewardship, a mindset echoed in the research of architect and sustainable urbanist, Steffen Lehmann. For example, Lehmann highlights ‘nature-based solutions’, as defined by the EU, are

“‘inspired and supported by nature, which are cost-effective, simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic benefits and help build resilience (…) and bring more, and more diverse, nature and natural features and processes into cities, landscapes and seascapes, through locally adapted, resource-efficient and systemic interventions’.”4

Both Lehmann’s findings and the Coast Salish practices show that environmental stewardship and economic growth can coexist, challenging the dominance of Homo Economicus.

Homo Absurdum, the playful and imaginative side of human nature, similarly pushes back against the rigid logic of capitalism. My recent piece featuring DEVO, for example, showed how embraced absurdity, irony, and satire could form a critique of conformity and dehumanization wrought by modern capitalist society.

DEVO’s music wasn’t just about self-expression — it was an act of resistance. They reminded us that creativity and play are as fundamental to human nature as rationality and profit-seeking. Homo Absurdum thrives in moments of rebellion, where we reject the idea that our worth is tied solely to economic productivity.

Even Adam Smith, the so-called father of modern economics, understood that human identity was more complex than the rational self-interest of Homo Economicus. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith emphasized empathy and care, reminding us that

“How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him.”5

Smith was also a product of his time, and his economic theories were socially constructed, shaped by the social and political environment of 18th-century Scotland, including the strong influence of Protestant religious values, which emphasized moral responsibility, hard work, and empathy toward others.

This brings us to an important realization: Homo Economicus is not the inevitable endpoint of human identity. It’s one track, amplified by the systems that hold power today. The human playlist is far more diverse, with room for care, play, connection, and environmental stewardship if we create the conditions to let these tracks play.

Economics is more than just markets and numbers — it’s a powerful force that shapes who we are. Through the lens of social constructionism, we see how economic systems construct certain identities, amplifying some parts of ourselves while suppressing others. In a world dominated by capitalism, Homo Economicus reigns supreme, but this doesn’t mean other tracks of human nature — like Homo Ecologicus, Homo Absurdum, or Homo Communis — are lost. These tracks are still present, waiting to be heard and made part of our collective human experience.

Immanuel Wallerstein, in his World-Systems Analysis, reminds us that historical moments like the French Revolution disrupted the structures that had previously determined the dominant identities of the time, legitimizing power in the hands of the people instead of monarchs or legislators.

He writes,

“The French Revolution propagated two quite revolutionary ideas. One was that political change was not exceptional or bizarre but normal and thus constant. The second was that ‘sovereignty’ — the right of the state to make autonomous decisions within its realm — did not reside in (belong to) either a monarch or a legislature but in the ‘people’ who, alone, could legitimate a regime.”6

In the same way, we too can challenge the dominant economic structures of today by reshaping the various ‘selves’ that make ‘ourselves.’

I agree with Brett Scott when he challenges us to remaster our economic tracks based on these potentialities. To bring forward the voices of care, creativity, and environmental consciousness, and let them play a stronger part of the mix. Homo Economicus may be the dominant track for now, but we have the power to remaster the mix. Let’s strive for all the tracks of the human experience to play their part in creating a new, shared, and well-balanced harmony.

Harvey, D. (2006). *Spaces of Global Capitalism: A Theory of Uneven Geographical Development*. Verso.

Massey, D. (1994). *Space, Place, and Gender*. Polity Press.

Mendenhall, Kate. "Organic Farmers Sprouting Up Across Iowa." The Gazette, 29 Oct. 2024. https://www.thegazette.com/agriculture/organic-farmers-sprouting-up-across-iowa/.

Schmitz, Mallory. "Experts: Beyond Corn and Soybeans, Farming's Future Has Plenty of Options." *Investigate Midwest*, 2 Nov. 2023. https://investigatemidwest.org/2023/11/02/experts-beyond-corn-and-soybeans-farmings-future-has-plenty-of-options/

Lehmann, S. (2023). *Reconnecting cities with nature: Developing urban spaces in the age of climate change*. *Emerald Open Research*. https://doi.org/10.1108/EOR-05-2023-0001

Smith, A. (1759). *The Theory of Moral Sentiments*.

Wallerstein, I. (2004). *World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction*. Duke University Press.