Hello Interactors,

As winter solstice nears in the northern hemisphere, this week brings a close to my explorations of economics. Next up is human behavior. I decided to stitch together this season’s economics posts into a single composite narrative. Upon reflection, I see a path my posts tend to take though it’s never premeditated. At least to my knowledge! In keeping with the theme of this post, it seems the uncertain path my essays take is a form of emergence.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

THE TREE OF MORAL SYMPATHY

‘Tis the season to be jolly, and with it comes this decision to volley. Real tree or fake tree? Or no tree at all. Such is the dilemma many find themselves in, at least in those places dominated by Christian tradition or influenced by Christian culture. The ‘real or fake’ Christmas tree analysis is how I was first introduced to ideas related to a circular economy.

It came through a class called “Sustainable Transportation from a Systems Perspective” as part of my master’s degree program. We were introduced to a 2009 study titled, “Comparative Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Artificial vs Natural Christmas Tree”. It came from a sustainable development consultancy in Montreal. Life Cycle Analysis looks at the environmental impact of the full lifecycle of a product or service from ‘cradle to grave.’

While the United Nations’ International Standardization Organization has determined a standard for how to conduct an LCA (ISO 14040), the interpretation of results can often include creative interpretations and conclusions.

This is particularly true if the LCA is conducted by a corporation or industry that may benefit from favorable LCA results. And you probably won’t be surprised to learn most LCAs are conducted or funded by private companies. LCA’s started popping up in the 1960s, but now they’re commonplace as companies jostle to present themselves as being environmentally sustainable and socially just through responsible and ethical governance – ESG. But measurements, evaluations, and analysis to determine an ESG score, like LCA’s, are also open to interpretation and manipulation. Consequently, ESG has lost its luster.

Sadly, the concept of a ‘circular economy’ is following a similar path. Circular economies take limited raw materials used to make goods and loops them back into the economy instead of throwing them away. The idea is to reduce, reuse, and recycle the inputs of an LCA and then repair the outputs to extend their lifecycle. But the term and practice of ‘circular economy’, like ESG, has also become diffuse and trendy.

A group of Industrial Ecologists, people who track the physical resource flows of industrial and consumer systems at different spatial scales, wrote in 2021,

“In seeking to maintain a growth-based economy, critics argue, the circular economy ‘tinkers with the current modus operandi’ of “consumerism, extractivism and (liberal) capitalism, while bearing the unrealistic expectation that the individual consumer will be able to mobilize largescale change. The circular economy is considered to encourage a reboot for capitalism that requires no radical change to institutions, infrastructures, and markets.”1

Calls for radical change concerning capitalism are strewn throughout history. The naturalist and scientist Alexander von Humboldt warned in 1800 of human induced climate change. He observed widespread systemic negative ecological impacts originated with infectious colonialism fueled by European and American profit seeking capitalists and imperialists. Between the abduction and trade of human slaves from Africa and local Indigenous populations to the overworking of soils to grow monocultural crops, Humboldt would not have been handing out top ESG scores to those very institutions who funded his explorations around the world.

Humboldt remained critical of colonialism and the brand of capitalism that came with it until the day he died. Ten years after Humboldt died another future critic of capitalistic colonialism was born, Mahatma Gandhi. By the time he was 76, in 1945, he called on his economist friend, Joseph Kumarappa, better known as J. C. Kumarappa, to further his ideas on Gandhian economics – a kind of circular economy.

Like Humboldt and other naturalists, Kumarappa observed the cyclical patterns in nature and sought economic practices that echoed them. He advocated for maintaining an economy of continuity and circularity with nature. Using the bee as a metaphor, he wrote,

“The bees etc. while gathering the nectar and pollen from these plants for their own good, fertilize the flowers and the grains, that are formed in consequence, again become the source of life of the next generation of plants.”2

Kumarappa studied at Columbia University under the progressive economist Edwin Seligman – a critic of exploitive forms of capitalism himself. Seligman encouraged Kumarappa to further his own ideas and critiques of traditional capitalistic economic orthodoxy. And he did. He wrote, “The Western plans are material centred. That is to say, they want to exploit all resources.”

Kumarappa and Gandhi also observed Western plans are to exploit all human resources for labor as well. In this regard, Kumarappa found inspiration in elements of Marxism. Marxism also provided a sociological explanation for why some Indians, Kumarappa included, rose to higher social class more than others. Though I suspect the passivist Gandhi probably would not approve of Marxist calls for civil disobedience. Marx himself was hardly socially obedient.

SHUN THE VICES OF PRODUCTIONSWEISE

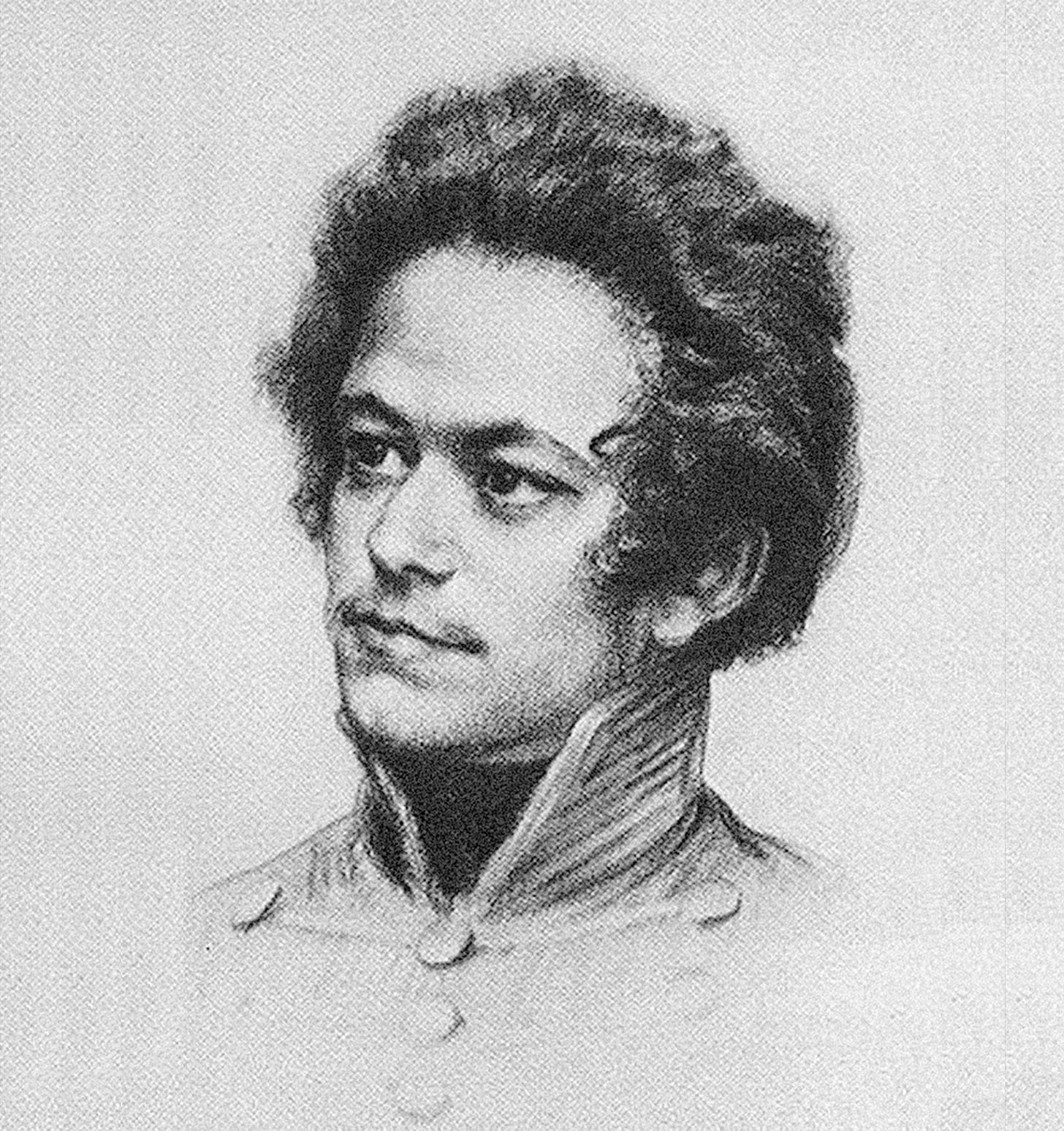

When Karl Marx was a freshman at a university in Bonn, Germany he was thrown in jail for drunken disorderly behavior. He joined a poetry club that was a front for a group of young radical’s intent on overthrowing the local government. There was also class conflict. Marx, the son of a modestly wealthy Jewish father, was considered a ‘plebian’ by the so-called ‘true Prussians and aristocrats.’ It got personal and led to a dual resulting in a bullet glancing the forehead of Karl Marx.3

Marx went on to study law and philosophy in Berlin and was a prolific writer. After leaving college, Marx became a journalist exposing elements of power structures present in the Christian led Prussian government. He believed their oppression suppressed the individual’s right to reason, engage, and speak with freedom of thought. His writing was radical enough to get him kicked out of the country.

He fled to Paris but was soon kicked out of France as well. He settled in England writing as a European correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune. He immersed himself in the work of the Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith in the reading room of the British Museum. He also witnessed the negative working conditions and poverty in burgeoning London factories that he attributed to Adam Smith’s single publication on economics, The Wealth of Nations.

Marx’s primary critique was summed up in a single German word: Produktionsweise. This can be translated as "the distinctive way of producing" or what is commonly called the capitalist mode of production. Marx believed this system of capitalism distinctly exists for the production and accumulation of private capital through private wealth. Private wealth accumulation allows for the purchase of land, buildings, natural resources, or machines, to produce and sell goods and services. This creates a wealth asymmetry between those who accumulate the wealth and capital and those laborers needed to produce the goods. This asymmetry yields profits that contribute to more private wealth accumulation which allows for the purchase of more capital. The rich get richer, while the poor get poorer.

But a closer reading on the moral philosophies of Adam Smith suggests Marx may have exaggerated the emphasis Smith had on the negative effects of industrial age economics. Reading the work of Adam Smith, and of his teacher and mentor Francis Hutcheson, reveals a good amount of the importance of sympathy for others who have suffered injustice. Smith writes, “All men, even the most stupid and unthinking, abhor fraud, perfidy, and injustice, and delight to see them punished.”4 He goes on to articulate the importance of justice for a society, and its economy, to be healthy and wealthy while recognizing few in power act to remedy injustices. He says,

“But few men have reflected upon the necessity of justice to the existence of society, how obvious soever that necessity may appear to be.”

Smith envisioned, as he wrote in Wealth of Nations, that “No society can surely be flourishing and happy of which by far the greater part of the numbers are poor and miserable.” A great deal of emphasis has been placed on two words that appear in a single instance in Smith’s popular book – “invisible hand”. But they first appeared in his earlier book The Theory of Moral Sentiments where he describes a selfish landowner’s moral decision to share a portion of his crop yield with the farmers who produced it. He writes,

“They are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life…”

Economics soon took a turn from Smith’s more prosaic philosophical economic interpretations. Instead of Smithonian ruminations on the moral justice of the state, liberty of free markets constrained by government, and the benevolent necessity of a cooperative societal collective, attention turned to the quantitative measuring of economic growth amidst a growing global British political economy. In 1862 W. S. Jevons published an essay titled "Brief Account of a General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy" and declare in an 1872 essay on principles of economics that its study "must be mathematical simply because it deals with quantities". Soon economics reduced complex human behavior, like the subjectivity of the value of a good or service, to a simple variable in an algebraic expression.

THE ONLY THING CERTAIN IS UNCERTAINTY

The atomization, classification, mechanization, and quantification of complex naturally occurring phenomena had long been popular with European Enlightenment thinkers. Isaac Newton believed in preformation – the idea that a Christian god had preformed every past, current, and future living being and packaged them up in miniature form into the male sperm. Every organ, limb, and joint were like components of a watch packed neatly in a microscopic vessel waiting to be released through the mystical act of intercourse.5

He, Rene Descartes, and others believed everything in the universe could be explained mathematically. The quest for certainty came both from these influential thinkers, but also religious authority. This came at a time of social revolutions, debates, and contestations over human rights, freedoms of religion, and ‘we the people.’ Mechanists married the certainty of mathematics with the certainty of their Christian god to explain the world. If nature and society lacked the linear precession of clocks, compasses, and mathematical calculations, they feared such uncertainty would unravel societal order and unleash chaos.

This video shows Richard Feynman lecturing on the importance of solving complex problems though a ‘Babylonian’ approach. This is in contrast with pure mathematics, as derived by Descartes and Euclid, that yields universally consistent solutions within the context of an abstracted world.

This love affair with mathematical algebraic abstraction and certitude seduced economists of the last three centuries. But one prominent British economist in the 1930s questioned this classical approach, John Maynard Keynes. Keynes was no stranger to mathematics; he was awarded a scholarship to study it at Cambridge. But he believed it was being dogmatized, misused, and misconstrued to bolster the legitimacy of economics by wrapping it in perceived certainty, logic, and accuracy. In his 1936 groundbreaking book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, he offers this criticism of traditional economics:

“our criticism of the accepted classical theory of economics has consisted not so much in finding logical flaws in its analysis as in pointing out that its tacit assumptions are seldom or never satisfied, with the result that it cannot solve the economic problems of the actual world.”6

Instead he called for “at least a partial attempt to incorporate the fact of uncertainty into an economic theory.”

He must have been on to something. Every capitalistic government in the world suffering from the 1930s depression instituted his policies until the 1950s. After World War II dominant economic theory shifted to the United States and the work of Milton Friedman and away from the recently deceased Keynes. Friedman erased the progress Keynes had made by embracing uncertainty in his economic models and returned to classical economic theory that deceptively models certainty. These theories assume humans act rationally and possesses perfect information that inform predictable decisions. These ‘new’ or neo-classical economists reduced the complexity and uncertainty of life to satisfy their calculations.

Economics cannot be explained with simple algebraic formulas. Complex economies call for an understanding of complexity. Enter complexity economics. Complexity economics is the application of complexity science to economics. Instead of assuming reductionist states of equilibria not found in the real world, complexity economics treats economics as a complex system of interdependent interactions. Out of these nested relationships emerge spontaneous uncertain outcomes that then loop back into the system in unpredictable ways.7

One of the pioneers in complexity economics, Brian Arthur, writes, “Complexity economics thus sees the economy as in motion, perpetually “computing” itself – perpetually construction itself anew.” This approach is reminiscent of John Maynard Keynes, but also of Alexander von Humboldt and other naturalists of the Enlightenment. It seems the history of the study and embrace of complex natural systems and spontaneous emergence of uncertain actions from an ‘invisible hand’ also perpetually constructs itself anew. Perhaps the looping nature of complexity in economics over time should be the central focus of what we now call ‘circular’ economy.

Still, the attraction of certainty never escapes us. Nature always seeks efficiencies, and we humans are part of nature. Perhaps this explains why many people are attracted to fake Christmas trees. These take the essence of a complex natural organism and reduce it to atomized parts that can be predictably assembled on a yearly cycle. A neo-classical Christmas tree. But as it happens, at least according to that 2009 LCA, like neo-classical economics, the fake tree has the bigger negative environmental footprint. Not by a lot, and certainly not compared to a daily driving habit, but it seems when it comes to getting a Christmas tree, we’re best to embrace the uncertainties and imperfections that come with finding that ‘perfect’ tree. Our family chooses to be like the naturalists and marvel at the complexity of the branches of a real tree and embrace its imperfections and uncertainties. Perhaps it’s time our economic models do the same.

ESG and the Circular Economy. Brad Weed. Interplace. October 8, 2022.

Gandhi and the Circular Economy. Brad Weed. Interplace. November 1, 2022.

That Bullet in Germany Nearly Altered the Economy. Brad Weed. Interplace. November 12, 2022.

Is the 'Invisible Hand' Pushing a Smith Myth? Brad Weed. Interplace. November 19, 2022.

Maybe it was Isaac Newton Who Needed Enlightened. Brad Weed. Interplace. November 25, 2022.

An Uncertain Alternative to a Certain Thatcher. Brad Weed. Interplace. December 03, 2022.

The Frenetic, Kinetic Cybernetics of Economics. Brad Weed. Interplace. December 10, 2022.