Hello Interactors,

Artificial intelligence divides us. To some, it’s a miracle waiting to solve humanity’s greatest problems. To others, it’s a creeping force, stealing our skills, jobs, and even autonomy. The truth, as always, is more complicated.

From sharpened sticks to smartphones, humans have always loved their tools — but at what cost? Plato feared writing would weaken memory; now we worry GPS dulls our sense of direction, calculators erode our math skills, and AI chips away at our ability to think creatively and critically. Are we creating marvels that strengthen us, or are we outsourcing so much that we’re making ourselves vulnerable?

What if the answer isn’t rejection or blind adoption, but finding a smarter balance? Let’s dive into what we gain, what we lose, and how interdependence with technology might just be our greatest strength.

DEPENDENCY WEAKENS COGNITIVE AGENCY

Let’s start with Plato. He famously criticized writing for weakening human memory.1 His complaint, though seemingly dramatic today, nonetheless echoes across centuries. Modern tools like calculators, spellcheckers, and GPS extend our cognitive reach — a concept known as extended cognition, where tools function as external parts of our thought processes.

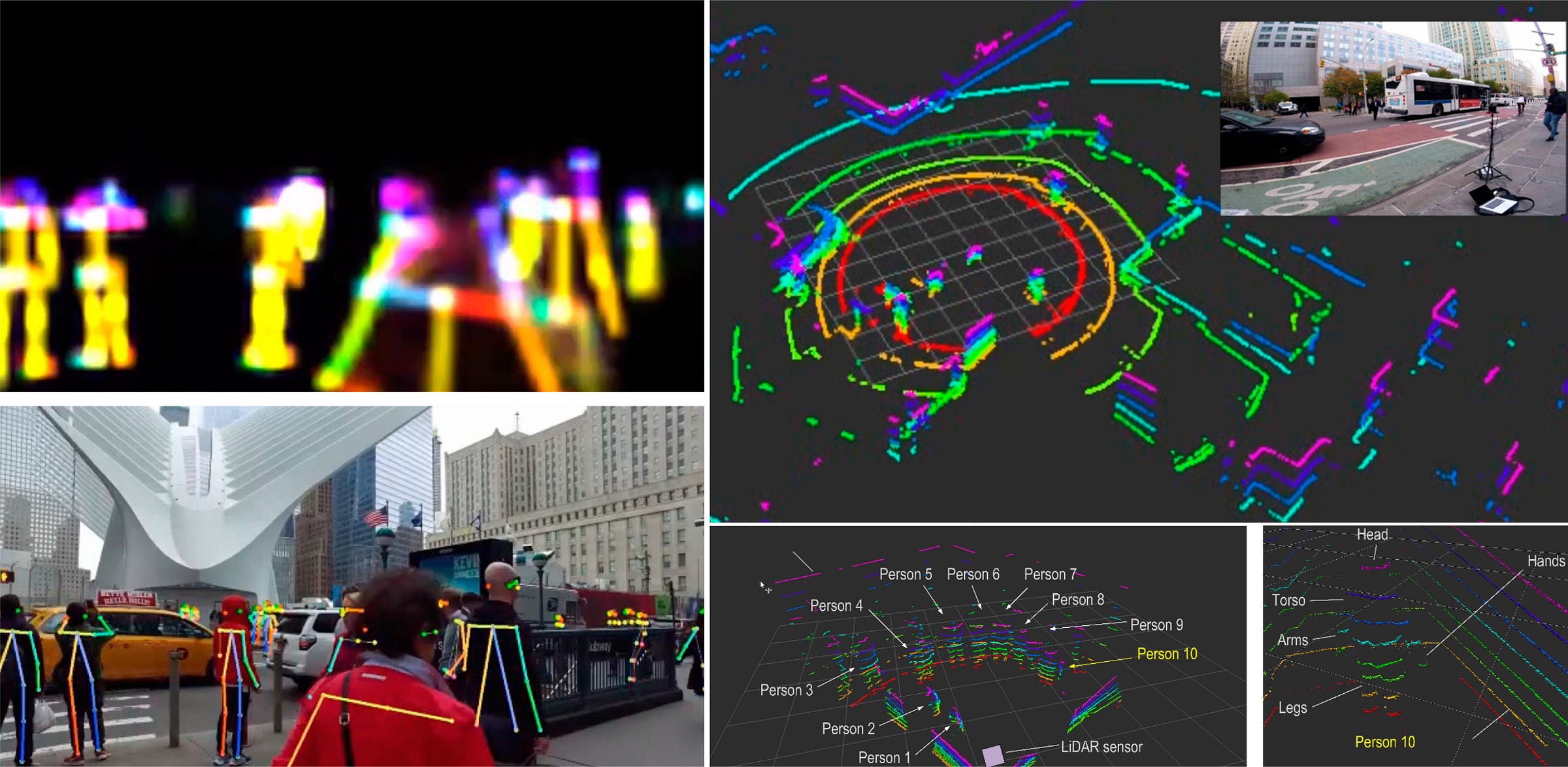

These tools are marvels of convenience, but they come at a cost. As geographer Paul Torrens highlights in his work on behavioral geography, tools like GPS don’t just help us — they sideline us.2 By reducing direct interaction with our environment, they bypass processes like navigating landmarks or forming mental maps. Over time, the skills we’ve refined for millennia quietly wither under the glow of our devices.

But there’s more to the story than atrophy. Torrens points out another subtle trap: the loss of what “small geographies” offer when we overly rely on tools like GPS and vehicles, both forms of extended cognition. “Small geographies” — our immediate, lived, day-to-day interactions with space — are rich in sensory details that inform navigation and spatial awareness. Walking through a neighborhood engages embodied perception, helping us notice landmarks, smells, textures, and even microclimates that shape our understanding of place.3

Yet, when we succumb to technologies that abstract these experiences into rationalized systems of larger geographies — like cities planned for efficiency rather than experience — we sacrifice this richness. GPS reduces navigation to turn-by-turn instructions, while vehicles reduce us to a brain in a box shielded from tactile, sensory feedback. This abstraction reshapes not only how we move through space but also how we sense and value it, distorting our relationship with our surroundings.4

History has plenty of warnings about over-reliance on rigid, top-down systems. During the Little Ice Age (c. 1300–1850), societies that had shifted to monoculture farming or depended on specific trade routes faced catastrophe when the weather turned erratic. Crops failed, rivers froze, and with them, the mills that powered daily life ground to a halt. Communities that had abandoned adaptive skills like crop diversification or local food storage found themselves particularly vulnerable, left scrambling to cope with nature’s prolonged unpredictability.

Catastrophes are brutal. Especially when our capacities are brittle. It’s the same trap we risk falling into today, as natural disasters increase in intensity and sometimes duration. We are more dependent than ever on our systems, certainly more than the Little Ice Age. We depend on power, electrodes, and grids of digital nodes embedded in a global network of interdependent modes.

Unlike in the 19th century, most of us don’t have a clue about growing food, let alone storing it. We’ve increasingly prioritized the efficiencies and abstractions of our institutionally driven lives over a more fundamental biological existence. Are we at risk of losing the cognitive and sensory richness that smaller, localized environments, or “small geographies”, uniquely offer? Would we survive an arid hell scape or another ice age?

STRENGTH IN INTERDEPENDENCE

Dependency is not a weakness — it’s indistinguishable from life. Humans exist because we rely on mutually dependent organisms — our gut microbes help us digest food and produce vital nutrients, our skin microbiome protects us from harmful pathogens, and even the mitochondria powering our cells were once independent organisms that became integral to our survival. Together, these partnerships form the foundation of our health and life itself. Our very bodies are home to incredible systems that operate as internal biological technologies, silently and effortlessly aiding our survival and navigation.

Take grid cells in the brain, for example. These specialized neurons, part of the brain’s spatial navigation system, act like an internal GPS. Grid cells encode distances and directions, enabling us to navigate our environment and construct mental maps of space without conscious effort.

Recent studies demonstrate how these grid cells work together in a way that forms a torus-like (donut) structure.5 The patterns of cognitive activity match up with the animal's movements as its position in the environment gets mapped onto a toroidal shape. Imagine a rat navigating a flat surface. As it moves, this research show its 2D planar coordinates are being translated to and from a 3D toroidal surface mapped on the inside of a gridded donut in its mind.

Our neurons interact with sensory inputs, seamlessly guiding us through environments through 3D biolelectric GPS wetware. Sensory modalities like kinesthetic and vestibular senses integrate with our neural systems to inform our perception of space and movement.6 In essence, our biological organs and limbs come equipped with intricate systems of extended cognition, working in coordinated harmony with the world around us. Just as our plastic and silicon devices extended our biological cognition, our cognition — our bioelectric calculators and wetware GPS — are extended forms of our environment.

The study of bioelectromagnetics spans biophysics, cellular biology, neuroscience, and regenerative medicine. It explores how electrical signals within and between cells govern critical processes like neural communication, cell behavior, and tissue regeneration. Biophysics examines the principles of ion flow and membrane potentials, while cellular biology investigates how bioelectric signals guide growth and differentiation. Emerging areas like systems and synthetic biology expand its applications and bioelectricity is key to understanding and engineering life’s electrical foundations.

These decentralized processes mirror key features of intelligence: sensing, processing information, and acting in a goal-directed manner. From resolving cellular disputes to coordinating regeneration, these bioelectric communication systems demonstrate how interdependence fosters adaptability.

Research already shows how synthetic technology can mirror these biological processes. Software acts as an extension of human adaptability rather than an artificial facsimile.7 Can we depend on this tech to instruct, not corrupt, the systems that make us up?

TOWARD ETHICAL TECHNICAL INTEGRATION

Electrobiology and the synthetic merging of technology with biology may seem futuristic, but it’s here. Moreover, we humans have a long tradition of infusing technology into the biological systems to sustain life. From vaccines to pacemakers, humanity has a history of cautiously adopting innovations that enhance our biology. While these technologies have saved countless lives, their integration hasn’t come without apprehension.

Take vaccines, for instance. While vaccines are now widely regarded as one of the greatest public health achievements in history, there have always been skeptics. Even now, after COVID-19 vaccines demonstrated the speed and efficacy of mRNA technology, new waves of fear and misinformation have followed.

These concerns echo a broader unease about technological advancements, seen not only with vaccines but also with the rise of AI. Obviously, a system that mimics human cognition raises questions about control, autonomy, and unintended consequences. Especially as it becomes infused with our biology.

But this dynamic mirrors the communication and deliberation found at the cellular level. Just as cells exchange bioelectric signals to coordinate action and solve problems, society deliberates at a larger scale, navigating conflicting viewpoints to determine whether and how to adopt new technologies.

Scale Theory8 offers a lens by looking at how systems and processes shift when moving between different scales, from the cellular to the societal. At one scale, bioelectricity reveals cells working collaboratively to heal wounds or regenerate tissue, a process both decentralized and adaptive. At a larger scale, society’s responses to new technologies — vaccines, AI, or bioelectric tools — follow a similar pattern of negotiation, fear, and eventual coordination.

The Eames Power of Ten explores how perspective shifts across scales—from the subatomic to the cosmic—reveal interconnected systems. Similarly, Scale Theory highlights how changes in scale reshape our understanding, ethics, and interactions, emphasizing the need to navigate complexity at every level. Together, they underscore the web of relationships that define our world.

While the scale differs, the core idea remains: complex systems deliberate and act in ways that ripple across their networks, whether they’re composed of cells or people. How much of this is metaphorical versus empirical is the work of complexity science.

I recently heard this sobering example of a synthetic creation rippling to cells: dating apps.9 These services use pair matching algorithms, made by an arbitrary human and influenced by networks of arbitrary people, actively manipulate our gene pool when certain biological pairings result in newborns. The same rippling occurs with zoning laws and the design and location of a bar or café…or even a town? My own biology came about when a decision to put a grain elevator in a small Iowa town rippled to my parents being paired resulting in three newborns.

Despite fears of these integrations rippling at various scales, history shows they can succeed when grounded in careful research, ethical oversight, and good intentions. Not every actor has good intentions, and not every rippling action is cause for celebration. After all, we can see with X and now Meta how quickly social media algorithms can be weaponized…and let’s be honest, that grain elevator in Iowa, while well intentioned, was constructed on stolen land.

Still, vaccines efforts can ripple to boost immune systems without fears of replacing or bypassing them; pacemakers can stabilize hearts without fear of replacing them; antibiotics can work with the body to fight infections and then disappear. These are rippling actions filled with good intentions and outcomes.

Tools like calculators and devices equipped with AI can also act with good intentions. They extend our cognition, enhance our ability to solve problems, and process information without replacing our underlying cognitive systems. Could bioelectric technologies follow this same path, amplifying natural cellular intelligence without overriding it?

Aristotle provides a counterpoint to Plato’s skepticism about writing. While Plato worried that writing would erode memory and internal knowledge, Aristotle saw value in external aids to thinking, such as writing and diagrams, as tools to organize and extend thought. In the same way, technologies like AI, GPS, and bioelectric tools have the potential to act as extensions of our cognition rather than replacements — but only if we integrate them thoughtfully.

The challenge lies in designing technologies that enhance human intelligence without bypassing the lived, embodied experiences that make us who we are. And even though spell checkers make us lousy our lazy spellers, and GPS lousy or lazy navigators, we are able to regain these skills when need be. We’re also able to coexist and even be enhanced by these synthetic extensions.

In nature and medicine, we find inspiring examples of how synthetic scaffolding can seamlessly integrate with natural systems. In regenerative medicine biodegradable scaffolds are used to repair damaged bones. These synthetic frameworks made of polylactic acid polymers provide a super structure for bone cells (osteoplasts) to grow into. As they guide the regeneration the scaffold gradually degrades, leaving behind only natural bone.

In coral reef restoration, artificial structures made of eco-friendly substances like calcium carbonate attract coral larvae and coastal creatures. Over time, these synthetic reefs become living ecosystems, blending seamlessly with their natural surroundings. If synthetic scaffolds can usher tissue repair and issue biocoenosis, can we align technology with biology? Can we merge artificial minds with organic matter? Can we complement our natural abilities without negating sensibilities? I think we can, because we already are.

Torrens, P. M. (2024). Artificial Intelligence and Behavioral Geography. In Handbook of Behavioral and Cognitive Geography.

Torrens, P. M. (2024). Ten Traps for Non-Representational Theory in Human Geography. Geographies, 4(2), 253–286.

(2)

Gardner, R. J., Hermansen, E., Pachitariu, M., Burak, Y., Baas, N. A., Dunn, B. A., ... & Moser, E. I. (2022). Toroidal topology of population activity in grid cells. In Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04268-7

Montello, D. R. (2024). Basic Concepts of Mind and Behavior. In Handbook of Behavioral and Cognitive Geography.

Levin, M., & Djamgoz, M. (2024). Bioelectricity: An Interdisciplinary Bridge into the Future. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.

DiCaglio, J. (2021). Scale Theory: A Nondisciplinary Inquiry. University of Minnesota Press. (Thanks to Michael Garfield for the reference during this talk.)

Eliassi-Rad, T. (2025). AI, Networks, and Epistemic Instability [Podcast episode]. In S. Carroll (Host), Mindscape Podcast. https://www.preposterousuniverse.com/podcast/2025/01/13/301-tina-eliassi-rad-on-al-networks-and-epistemic-instability/