Hello Interactors,

In 2002, when I was at Microsoft, Bill Gates launched an initiative called Trustworthy Computing (TwC). The internet was fresh, ripe for malicious attacks, and Microsoft was a big target. Memos were issued, posters were printed, teams were formed, and code was fortified. And in the case of hidden Easter Eggs in Windows and Office — removed. Internal hacks weren’t a good look.

Trust is everywhere these days — politicians vow to restore it, social scientists try to measure it, and brands continue to demand it. U.S. money says to trust God, and it seems we’re now asked to trust Musk. Clearly trust isn't universal; it's shaped by our views of and interactions with power, place, and institutions.

Lately, trust feels harder to hold onto. It's not just social media, politics, or government failures — the spaces where trust once thrived are disappearing. Town squares, shops, and local newspapers are vanishing, replaced by fragmented digital alternatives. Trust may be declining; but it's mostly shifting, and not always for the better.

Trust won't simply "return" with a memo from Bill. Nor from Trump, Zuck, Musk, or Jeff. Even if they did, they’d likely soon be tossed in the Trumpster Fire. These figures make us question who is gaining trust, who is losing it, and what these new patterns mean for democracy and social cohesion?

SELF-TRUST LOST TO CIVIC COST

Trust begins with confidence in what we know and perceive. We rely on self-trust to navigate the world — to make decisions, assess risks, and interpret so-called reality. Self-trust relies on the brain’s ability to process uncertainty and predict outcomes. The prefrontal cortex (the brain’s decision-making hub) assesses risks based on past experiences, while the anterior cingulate cortex (a small but crucial center between hemispheres) detects conflicting information, signaling when to doubt or adjust beliefs.1 When these systems function well, self-trust remains stable.

But in an era of conflicting information, the brain is flooded with competing signals, making it harder to form confident judgments. Chronic exposure to uncertainty and misinformation can overstimulate these networks, leading to decision paralysis or over-reliance on external authorities.2

Yet self-trust isn’t just a cognitive process — it is also shaped by social and epistemic (knowledge-related) factors. Prominent NYU philosopher Miranda Fricker, known for her work on epistemic injustice, argues that trust in one’s own knowledge isn’t formed in isolation but depends on social reinforcement and being recognized by others as a credible source of knowledge.3

When individuals experience repeated epistemic injustice — being dismissed, ignored, or denied access to authoritative knowledge — they internalize doubt, weakening their own cognitive autonomy. Without reliable social validation or consistent feedback from their surroundings, self-trust erodes. This is not just a psychological state, but a consequence of power structures that shape who gets to "trust" their own judgment and whose knowledge is devalued.

In the past, people validated their understanding through direct experience and social reinforcement. I remember watching TV anchor Walter Cronkite as a kid with my family in Iowa. He was the source of authoritative knowledge for us all. We also learned from trusted local voices and community newspapers. The Des Moines Register was won of the most influential and trusted regional papers in the country. It won 16 Pulitzer Prices from 1924 to 2010 — the first being for the work of syndicated editorial cartoonist “Ding” Darling.

Now, those anchors have weakened. These knowledge sources have been replaced by curated digital landscapes, where information is sorted not by credibility, but by engagement metrics and algorithmic amplification.4 One case study shows that this shift can lead to a growing public reliance on self-reinforcing information bubbles, where trust in knowledge is shaped more by network effects than by institutional credibility.5 This creates a paradox: people have more access to knowledge than ever before yet feel less certain in what they know and trust.

This crisis of self-trust extends beyond information. It is not just about struggling to determine what is true, but also about uncertainty over how to act in response to a changing political and social landscape. Despite declining trust in political leaders, there is evidence public support for democracy remains strong.6 We may doubt the players, and even the game, but our faith in democracy mostly stays the same.

This gap — between distrust in leadership and belief in the system — creates the sense of civic uncertainty we all feel. It’s not hard to find those who once trusted their ability to participate meaningfully in democracy but now feel disengaged, disoriented, or discombobulated. They’re unsure whether their actions can have any real impact.

Voting, town halls, and community groups used to feel like meaningful ways to engage, but when institutions seem distant or unresponsive, they lose their impact. At the same time, digital activism and decentralized movements offer new ways to get involved, but they often lack clear legitimacy, accountability, or real influence on policy.7

Rising polarization, disinformation, and the decline of local journalism have made it harder for people to trust democratic institutions. Many still believe in democracy but doubt whether their actions make a difference. This uncertainty fuels disengagement, creating a cycle where institutions fail to respond, deepening distrust. The real crisis isn’t about rejecting democracy — it’s about struggling to find meaningful ways to participate in a system that feels increasingly unresponsive.

STRANGERS ONLINE, NEIGHBORS OFFLINE

If trust in ourselves grounds what we know, trust in others helps it grow. We nurture it through everyday interactions — recognizing familiar faces, exchanging small favors, and feeling a shared connection to the places we live. But as communities change and people become more disconnected, those trust-building moments start to wither.

Many neighborhoods once relied on deep social networks woven through personal relationships — longstanding ties between neighbors, trust built through shared spaces, and informal support systems that provided stability.8 Small businesses, community centers, and local institutions weren’t just places of commerce or service; they were gathering spots where people formed relationships, exchanged information, and reinforced a sense of belonging. But economic restructuring, gentrification, and urban development have disrupted these networks, dismantling the infrastructure that once sustained social trust.

As housing costs rise, longtime residents are pushed out, taking with them the relationships and shared history that held communities together. Gentrification swaps deep local ties for a more transient crowd, while big corporations replace small businesses that once fostered real connections. Where shop owners knew customers by name, now it’s all about quick transactions, leaving fewer chances for meaningful interaction.

Adding to this shift, the rise of online shopping and door-to-door delivery has further reduced the need for everyday in-person interactions. Where people once ran into neighbors at the local grocery store or chatted with shop owners, now packages arrive with a quick doorstep drop-off, and errands are handled with a few clicks. This convenience comes at a cost, replacing casual, trust-building encounters with isolated transactions, further weakening the social fabric of neighborhoods.

Car dependency doesn’t help. Car dependence doesn’t just reduce social interactions — it reshapes them. As urban sprawl spreads people further apart, longer commutes and car-centric infrastructure leave less time for community engagement, weakening neighborhood ties.9 Public transit, one of the few remaining shared civic spaces where people of different backgrounds interact, has been deprioritized, reinforcing isolation.

Yet, denser urban living isn’t necessarily the fix. While some advocate for more compact, walkable communities to counteract social fragmentation, there is research that shows density alone doesn’t guarantee stronger social bonds.10 High-rise developments and mixed-use neighborhoods may put people physically closer together, but without intentional social infrastructure — such as well-designed public spaces, accessible community hubs, and policies that foster local engagement — denser environments can be just as isolating as car-dependent sprawl.

At the same time, digital life has transformed how we interact. Social media and online communities have expanded the scope of connection, but often at the cost of place-based relationships. Online, people tend to engage with those who already share their views, reinforcing ideological silos rather than broadening social trust. Meanwhile, interactions with strangers — once the foundation of civic life — become more fraught, as society sorts itself into parallel realities with fewer common reference points.

Yet social trust is not entirely collapsing. While some forms of trust — particularly trust in strangers and diverse social networks — are declining, alternative forms of community trust are emerging. Digital spaces, local activism, and mutual aid networks offer new avenues for rebuilding trust, even as traditional community bonds weaken.11 The question is not whether trust exists, but what kinds of trust are flourishing, and at what cost?

CONNECTED OR CONNED

At the broadest scale, institutional trust is what binds societies together — it’s the belief that governments, media, and public institutions operate with some level of fairness, competence, and accountability. But in many places, that trust has been unraveling for decades.

This isn’t just about political polarization or disinformation. Much of the erosion of trust in institutions comes from lived experience. Local governments used to be the most trusted level of governance, but years of budget cuts and privatization have left them struggling to provide basic services.12 To stay afloat, many cities have outsourced essential services to private companies, prioritizing short-term cost savings over long-term community needs.

As a result, public services have become more uneven, with some neighborhoods getting what they need while others are left behind. Instead of feeling like a reliable support system, local government now often seems distant, underfunded, and unable to truly serve the people who rely on it most.

In the United States, "austerity urbanism" has led to mass school closures in cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, cuts to public transportation in Detroit, and the deterioration of water infrastructure in places like Flint and Jackson.13 Public housing budgets have shrunk, forcing cities to rely on private-public partnerships that often lead to rising rents and displacement.

Rather than being experienced as sources of support, local governments are increasingly perceived as punitive forces. In some cities, emergency financial managers — appointed to balance municipal budgets — have slashed services and sold public assets with little public input, reinforcing a sense that government is distant, unaccountable, and incapable of serving its residents.14 The result is a feedback loop of distrust: as public services decline, citizens disengage, reinforcing the very conditions that make institutions seem ineffective or absent.

The decline of trust in representative institutions does not mean trust in governance itself has collapsed. Research shows that while trust in elected officials and legislatures is declining, trust in implementing institutions — such as courts, police, and civil services — has remained relatively stable in many democracies.15 This suggests that while citizens may distrust politicians and their decision-making, they still believe in the structural functions of governance itself, even if that trust is increasingly conditional and unevenly distributed.

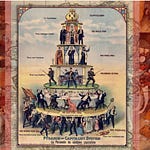

However, as local trust declines, people are looking elsewhere for authority. In some cases, this has meant turning to charismatic leaders who position themselves as restorers of stability in response to perceived governmental dysfunction. Right-wing populist movements like Trumpism — with authoritarian-leaning politicians funded by libertarian-leaning capitalists — have capitalized on this distrust, framing themselves as defenders of "the people" against an out-of-touch political elite.

Meanwhile, others have sought alternative governance structures to fill the void left by failing institutions. For example, food policy expert Katie Morris highlights how some cities, fed up with national inaction on food insecurity, are taking matters into their own hands.16 She highlights how “Right to Food Cities” are stepping up to provide food assistance and support local food systems, proving that even when higher levels of government fall short, local action can still make a difference. Seattle’s Food Action Plan is one example.

While these efforts demonstrate local governments’ ability to function as alternative governance models, they also highlight the fragmentation of trust — where some communities invest in grassroots action while others retreat into authoritarian appeals for order.

It seems trust isn’t disappearing — it’s being redistributed. Some find security in bureaucratic institutions like the courts and civil service, while others seek top-down leadership in populist figures or create community-driven governance alternatives. Either way, this redistribution deepens political fragmentation, making it harder to achieve widespread institutional legitimacy.

Each of these crises — self-trust, social trust, and institutional trust — feeds into the others. When people struggle to trust their own judgment, they become more hesitant to engage with their communities. When social networks weaken, people feel more isolated and disconnected from larger institutions. And when institutions fail, people turn inward, relying on personal networks or ideological affiliations over collective governance.

But just as these crises reinforce each other, so too can their solutions. Restoring trust isn’t about recreating an idealized past — it’s about understanding how different visions of community shape trust today. Many people look to historical models of social cohesion, whether rooted in low-density suburban stability of the 1950s or high-density, transit-oriented neighborhoods of the late 1800s, as templates for rebuilding trust.

These views, rooted in social capital theory — the idea that strong community ties build trust and cooperation — recognize that our surroundings shape how we connect. While social capital can foster civic engagement, it also has a darker side.

Political analyst Adam Fefer, who studies democratic resilience, highlights how tight-knit networks have fueled anti-democratic movements in the U.S., spreading misinformation rather than broadening trust.17 The January 6th attack wasn’t spontaneous — it was driven by organized groups leveraging veteran organizations and faith communities to mobilize action. Historically, exclusionary civic groups have also reinforced segregation and voter suppression, showing that not all social capital strengthens democracy.

However, these same civic networks can protect democracy, as seen in union-led economic shutdowns and business leaders opposing political extremism. This highlights a crucial fact: the impact of social capital on civic well-being varies based on its structure, who it empowers, and its intended purposes.

Rather than looking backward, we need to build trust in ways that fit today’s world—both digital and physical. That means strengthening local knowledge networks, rethinking where and how we connect, and recognizing that much of life now happens online, from social interactions to doorstep deliveries. While shared public spaces still matter, we must also find ways to foster trust in a world where community, commerce, and governance are increasingly digital.

And it means rethinking governance, not as a distant authority, but as something more active and responsive—an ongoing process that truly gives people a stake in shaping their communities. Perhaps the real challenge isn’t in longing for a past version of civic life, but in asking how we can create the conditions today that make people feel connected, capable, and truly invested in the future of their neighborhoods. How do we build a world where trust isn’t just a distant trace, but a tangible part of our daily interactions with people and place?

Botvinick, M. M., Cohen, J. D., & Carter, C. S. (2004). Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: An update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(12), 539-546.

Hertz, U., Palminteri, S., Brunetti, S., Olesen, C., & Bahrami, B. (2021). The computational neurobiology of trust. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(7), 596-608.

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press.

Forster, C. M., & Wong, N. (2024). Rightfully-placed blame: How social media algorithms facilitate post-truth politics. Bristol Institute for Learning.

Kim, D., & Kokuryo, J. (2024). The role of networked narratives in amplifying or mitigating intergroup prejudice: A YouTube case study. Societies, 14(9), 192.

Valgarðsson, V. O., Lacey, J., & Norris, P. (2024). A crisis of trust? Declining institutional trust in democracies. British Journal of Political Science.

Cho, A., Byrne, J., & Pelter, Z. (2020). Digital civic engagement by young people. UNICEF Office of Global Insight and Policy.

Chaskin, R. J., & Joseph, M. L. (2024). "Positive" gentrification, social control, and the "right to the city." Delft University of Technology.

Nguyen, D. (2010). Evidence of the impacts of urban sprawl on social capital. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 37(4), 610-627.

Ibid

Bernstein, A. G., & Isaac, C. A. (2023). Gentrification and community engagement: Can trust be rebuilt? Journal of Urban Affairs.

Kim, Y., & Warner, M. (2020). Pragmatic municipalism or austerity urbanism? Understanding local government responses to fiscal stress. Local Government Studies, 47(4), 521-543.

Peck, J. (2012). Austerity urbanism: American cities under extreme economy. City, 16(6), 626-655.

Theodore, N. (2020). Governing through austerity: (Il)logics of neoliberal urbanism after the global financial crisis. Journal of Urban Affairs, 42(1), 31-47.

6

Morris, K. (2024). Right to food cities: Local governments in the fight against austerity. Journal of Human Rights Practice.

Fefer, A. (2024). Introducing the Pillars of Support Project. Horizons Project. Retrieved from