Hello Interactors,

Today we’re branching into topography and the role western colonial expansion plays in the creation and articulation of our naturally occurring geography. Most of us are not very skilled at critiquing the role maps have played in shaping how we see the globe and the people on it. But I’m optimistic that when we do we can better confront the boundaries that maps have created between people and place.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

NAME THAT PLACE

I spent last April talking about how the United States was surveyed and diced in little squares that are featured in our maps today. It was a technique ripped out of ancient Rome as a way to rationally quantify space across massive swaths of land. The United States perfected gridded cartesian cadastral cartography, but drawing little lines on paper as a means of assessing, assuming, and asserting control over land had been done for centuries by European colonial settlers around the world – beginning in the Renaissance.

The Renaissance accelerated mapping. This was an era of discovering new knowledge, instrumentation, and the measuring and quantification of the natural world. Mercator’s projection stemmed from the invention of perspective; a word derived from the Latin word perspicere – “to see through.” European colonial maps were drawn mostly to navigate, control, and dominate land – and its human occupants. We have all been controlled by these maps in one way or other and we still are. Our knowledge of the world largely stems from the same perspective Mercator was offering up centuries ago. The entire world sees the world through the eyes of Western explorers, conquerors, and cartographers. That includes elements of maps as simple as place names.

Take place names in Africa, as an example. The country occupied by France until 1960, Niger, comes from the Latin word for “shining black”. Its derogatory adaptation by the British added another ‘g’ making a word we now call the n-word. But niger was not the most popular Latin word used to describe people of Africa, it was an ancient Greek derivative; Aethiops – which means “burn face”. If you replace the ‘s’ at the end with the ‘a’ from the beginning, you see where the name Ethiopia comes from.

Even the name of my home state of Iowa has dubious origins. Sure it’s named after the Indigenous tribe, the Iowa or Ioway, but the Iowa people did not call themselves that. They referred to themselves in their own language as the Báxoje (Bah-Kho-Je). They settled primarily in the eastern and south eastern part of the land we now call Iowa. Most of them were forced to relocate to reservations in Kansas and Oklahoma. It’s believed the name Iowa, came from a Sioux word – ayuhwa which means “sleepy ones.” It would be like the south winning the Civil War and then turning around and declaring the region to their north henceforth be referred to as: Yankees.

Even the word Sioux is a French cheapening of a word from the Ojbiwe people– Nadouessioux (na·towe·ssiw). The Sioux were actually a nation combined of the Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota people. They referred to themselves as Oceti Sakowin (oh-CHEH-tee SHAW-kow-we) or “Seven Council Fires”. They covered the sweeping plains of most of what we now call Minnesota; which stems from the Dakota phrase Mni Sota Makoce – “where the waters reflect the sky”. They extended south to the northwest corner of so-called Iowa and east to the more aptly named state of South Dakota.

These people were expelled from Minnesota after the Dakota War of 1862. They continue to suffer today the pains felt by America’s largest mass execution in history at the hands of none other than Abraham Lincoln. Just months after signing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln ordered 38 Dakota and Lakota men to be hung. Dissatisfied with the pace and politics of the makeshift trial of 303 Indigenous people, he decided on his own who should live and who should die. On April 23rd, 1863 the United States declared their treaties with the Lakota and Dakota null and void, closed their reservations, and marched them off their land. It took until this year, 2021, for the United States to give a southern sliver of land back to them. And in Northern Minnesota they’re still fighting to protect the water that reflects the sky.

MAPS AND MATH FROM A MAN FROM BATH

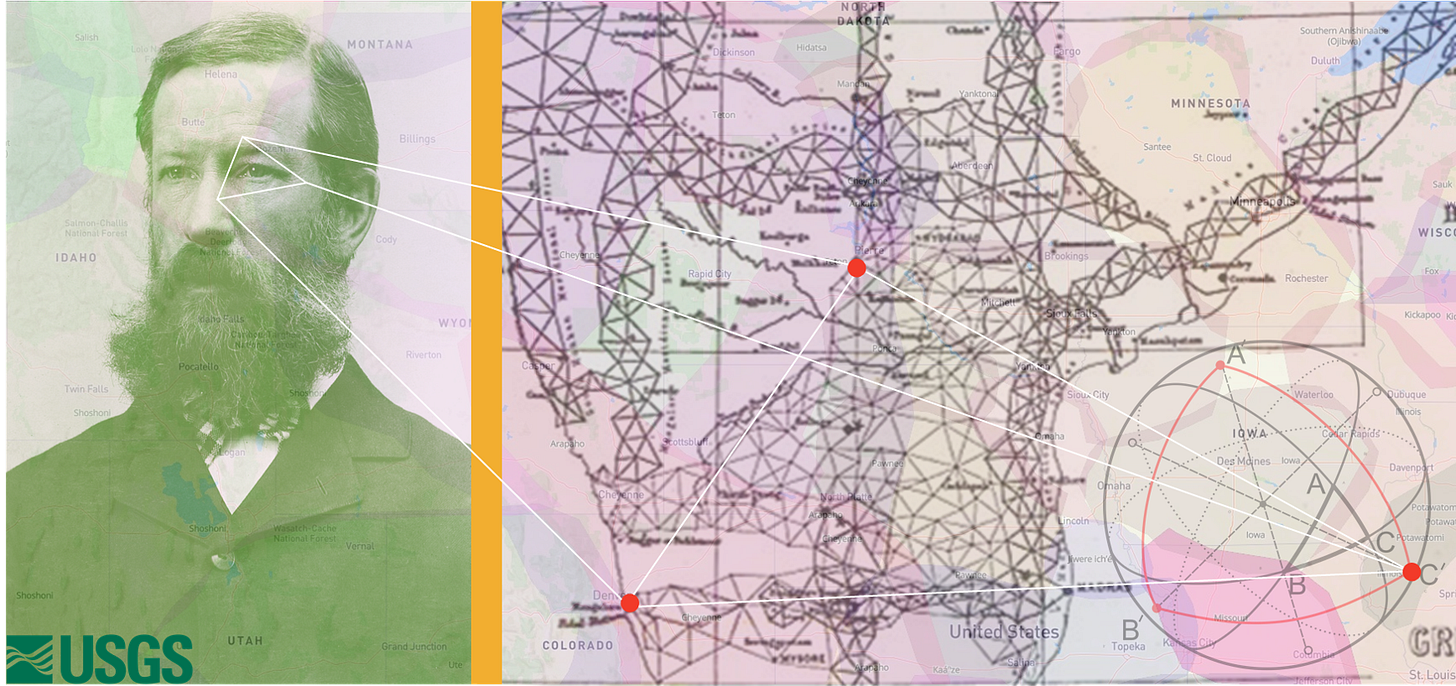

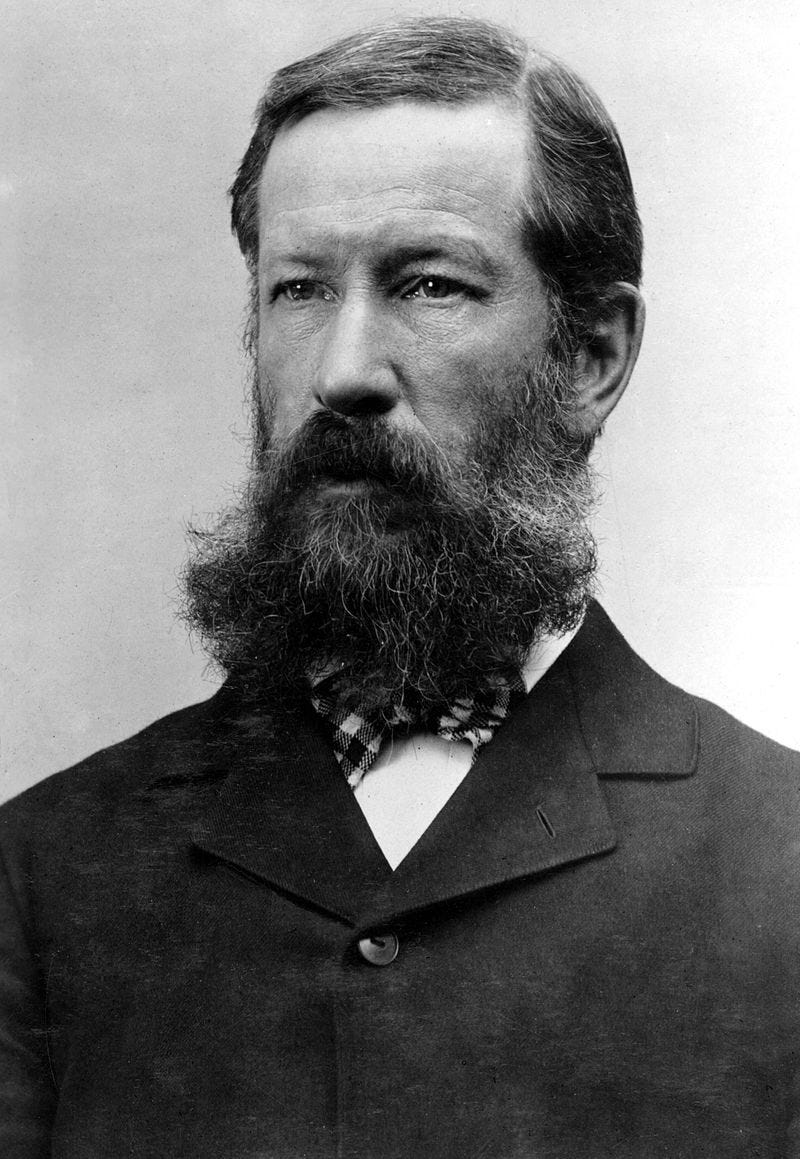

There’s another Westernized place name just west of where the Dakota and Lakota people thrived called Gannett Peak. It’s the tallest mountain in the state of Wyoming and is part of the Bridger-Teton range. I’m sure you’ve heard of the more popular neighboring range, the Grand Teton’s; another notable (and sexist) French place name which means – ‘Big Boobs’. Gannett Peak is named after Henry Gannett – the father of American mapmaking.

Born in Bath, Maine in 1846 he went on to graduate from Harvard’s Lawrence Scientific School in 1869. After some time in the field documenting geology from the Great Lakes to the mines of Colorado he returned to Harvard for a degree in mining engineering. He spent a couple years working at the Harvard College Observatory making maps and calculating the building’s precise longitude.

He then was hired as the chief astronomer-topographer-geographer by the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories in 1872. A mouthful. Perhaps daunted by such a long name for a department charged with precision and clarity of information, the USGGST was shortened to USGS in 1779 – the U.S. Geological Society.

Some claim Gannett lobbied for USGGS in an attempt to maintain the word geographical and not just geological. If so, he was likely outvoted by his boss and prominent geologist, Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden. His book, The Great West: its Attractions and Resources gives you a clue as to why geologists were maybe more revered than geographers in the late seventeen and eighteen hundreds. After all, there’s gold in them there hills.

The study of naturally occurring geometric properties and their spatial relations over a continuous plane is the work of topology. Documenting and surveying those studies is the work of a topographer. And the artifact they generate is called a topographic map. The first large scale topographic mapping project was Cassini’s Geometric Map of France in 1792. Then, in 1802 the British followed with the highly precise topographic map of India. As I’ve noted in previous posts, the earliest surveying and mapping of the British colonies and the United States were funded and controlled by government backed private companies like the Hudson Bay Company in the 1600s and the Ohio Company of Associates in the 1700s.

IT’S UP TO YOU TO QUESTION YOUR VIEW

The topographic map of India was also directed by a British colonizing super-spreader the East India Company. They, together with the British government, had been at it for 200 years already. But in the early 1800s they were seeking accuracy. They wanted far more precise control over the Indigenous land, resources, trade, and people. The people of India are second to Africa in genetic diversity and emerged via Africa through the Indus River valley; hence the name India. This massive southeast Asian continent was first named by the Spanish or Portuguese – India is Latin for “Region of the Indus River”.

The map that the East India Company commissioned in 1802 is called the Great Trigonometrical Survey. Trigonometry had already been awhile. In 140BC its Greek inventor, Hipparchus, used it, as the British did, for spherical trigonometry – the relationship of spherical triangles that emerge when three circles wrapping around a sphere intersect to form a spherical triangle. It’s used to measure the spherical curvature of the earth and was employed with precision by the East India Company using instruments with cool names like theodolite and Zenith sector. What resulted was a map of India featuring a fine-grained triangulated lattice accurately depicting the designated borders of British claimed territories. It was also the first accurate height measurements of Mount Everest, K2, and Kanchenjunga. Those heights were surveyed by Indigenous Tibetan surveyors who were secretly hired and trained by the British. Europeans were not allowed into Tibet at the time, so the surveyors had to pretend they were just hiking. This trigonometrical triangulated technique was the first accurate measure of a section of the longitudinal arc. The same arced sections that defined the curved edges of Henry Gannett’s topographic quadrangle mapping system which he perfected seventy years later on the other side of the globe at an arc distance of roughly 8,448 miles or 13,595 kilometers.

Gannett’s career arc makes it easy to see why he figures prominently in American geography. Following is just a sampling of his contributions.

He was the first geographer assigned to the census for the country’s tenth census survey. Gannett was responsible for drawing the first census tracts and invented the enumeration of districts based on population and geography.

He chaired the Board of Geographic Names and later wrote a book on the history of United States place names. You can read a digitized version online. It includes a surprisingly long list of place names across the country and their origins.

He demarcated the first 110,000 miles of national forests and served as Teddy Roosevelt’s research program director for his National Conservation Commission which projected future natural resource use.

He helped form the National Geographic Society, Association of American Geographers, and other astronomy and geology clubs.

He published two hundred articles on human geography, cartography, and geomorphology all while editing a handful of journals and publishing textbooks.

The topographical techniques and programs Gannett pioneered were used all the way to the 1980’s and 90’s as GPS and computers took over. As amazing as his work was, it was no match for satellite imagery, GPS, and computer imaging. The topography he painstakingly surveyed and mapped is now available to anyone with access to a computer and an internet connection.

Gannett was one of many geographers throughout the history of western colonization. Sure he was more influential than most, but they were all tasked with the same thing. Whether it was triangulating British territories in India, finessing French regions in Africa, or delineating Dutch districts in Brazil they were all measuring, mapping, and manipulating how others should see the world. It’s the paradox of mapmaking. No matter your intent, whatever line you draw will reflect the bias you bring.

Mercator was biased by perspective because that’s what the culture of his time led him to do. Gannett mapped natural occurring features of the land because the mapping of minerals and other natural resources was in high demand. Iowa was named Iowa because that’s what they knew. Even attempts to counter-map the dominance of cartesian colonial cartography can’t escape its own bias. Nobody can. But we live on a melting planet, so our days remain a few. If we’re going to survive this calamity, we must see that our thoughts are skewed. So the next you look at a map, consider its point of view. If we all do this together, we can invent a world anew.

Sources:

Henry Gannett Chapter. The History of Cartography, Volume 6: Cartography in the Twentieth Century. Edited by Mark Monmonier.

Wikipedia.