Hello Interactors,

This is part one of a two part series on the role of economics in the holiday season. We’re a week away from Thanksgiving, but Christmas has already started to enter our lives. If it feels like it keeps creeping closer to Halloween, that’s because it is. Little did I know, it actually started out that way.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

HOUSE INVASION

It was 9:00 on Christmas night when four men forcibly entered the house. John Rowden, his wife, their adopted son, and a live-in helper, Daniel Poole, were all home. The four men made their way to the living room, sat on the couch in front of the fire, and starting singing Christmas carols. Clearly drunk, at some point one of the men turned to Rowden and said sarcastically, “How do you like this, father?” They demanded alcohol as payment for their ‘entertainment’. Rowden didn’t like it at all and asked them to leave.

They had heard Rowden had fine wine in his collection. They said they’d happily pay him for the alcohol later, but demanded the wine now. Rowden’s wife stepped in reminding them that their house was not a bar and they should leave. Much to their surprise, the men did; only to return minutes later claiming they had the cash to pay for the wine.

Fearing the scoundrels would break in if they didn’t take the money, the Rowden’s decided to sell them a bottle of their prized wine. But first they demanded proof that the men had the money. Rowden cracked open the door and one of the men shoved fake money in his wife’s face as the others tried to enter the house.

The Rowden’s, with the help of Daniel Poole, managed to push them back and secure the door. The four men appeared to have given up. But moments later they heard them yelling sardonically from outside, “hello.” Poole tried to reason with them. He reminded them that it was Christmas night and they should be home. They saw this as a provocation and challenged Poole to come out and make them go home.

Poole refused, of course, so they began throwing rocks at the house. They pried away siding, destroyed rockery, fences, and tore down poles. After an hour and a half of persistent vandalism, it finally subsided and the family was safe and sound. The house? Not so much. Merry Christmas.

This true story is from 1649 and took place in Salam, Massachusetts. Two of those four men were later implicated in the Salem witch hunts. These intrusions were a common occurrence in the colonies during the holiday season, but more so in England. These four men were wassailing. Today we might call it caroling, but at the time it was really more a combination of Thanksgiving, Mardi Gras, trick-or-treating, and caroling. We don’t run into many drunk carolers these days, but we would have in 17th century England and their colonies.

The Puritan settlers outlawed wassailing after colonizing. In fact, they banned any celebration of Christmas. Because the bible makes no mention of the birth of Jesus on any particular date, there was no cause for celebration. Of course, there was little cause for celebration among the Puritans at all; especially excesses of revelry, alcohol, and sex.

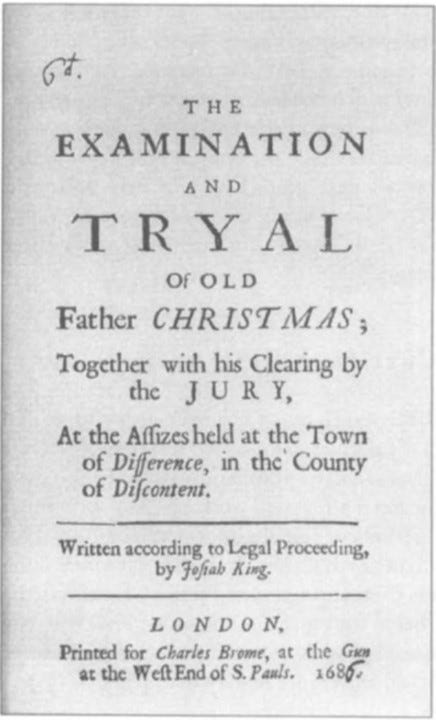

The Puritans tried banning Christmas in London too. It prompted a book to be written in 1686 called The Tryal of Old Father Christmas. It featured a Puritan jury made up of “Mr. Cold-kitchen”, “Mr. Give-little”, and “Mr. Hate-good.” Perhaps these characters inspired Charles Dicken’s character, Ebenezer Scrooge, 150 years later.

TRICK OR TREAT, SMELL MY FEET, GIVE ME SOMETHING GOOD TO EAT

The Rowden’s were a relatively affluent family who owned a pear orchard from which they made pear wine or cider, known as “perry”. Those four young men were of a lower class, possibly even laborers for his orchard, and they came to Rowden’s house to be merry with his perry.

It was common practice throughout Europe and England for wealthy land and farm owners to treat their lower class workers to a meal and/or gifts in late November and early December. After what must have been an intense and laborious season of harvesting, canning, slaughtering, and preparing for the coming winter months, December marked an end to a fruitful season worth celebrating. December 6th was the customary end of the harvest season in Western Europe, just a week and a half after America’s modern-day traditional harvest celebration – Thanksgiving.

To recognize and honor their hard work, it became customary for workers to exchange gifts with their masters or employers. Some exchanges were initiated from the lower class workers and other times by the upper class employers. But every wealthy land owner knew that if they didn’t so something to commemorate their worker’s labor, they risk workers taking it upon themselves to come knocking. Just as those four men did to old man Rowden, singing,

Come bring, with a noise,

My merrie, merrie boys,

The Christmas log to the firing;

While my good dame she

Bids ye all be free [i.e., with the alcohol]

And drink to your heart’s desiring…

The upper class quickly learned that it’s best to open their doors to the peasant class, feed them, entertain them, and send them on their merry way…or else. As evidenced in this little jingle,

We’ve come here to claim our right…

And if you don’t open up your door,

We will lay you flat upon the floor

While I’m sure there were examples of benevolent exchanges between classes, the ritual also served as an explicit reinforcement of social order. You’re down there and we’re up here. Don’t think that we’re equals. We have the goods and you come begging. And begging they did, singing,

Again we assemble, a merry New Year

To wish to each one of the family here

May they of potatoes and herrings have plenty

With butter and cheese, and each other dainty

Christmas was a time when the poor were excused for begging. If they were not happy with what was offered, they took revenge. Again, a bit like Halloween. Give me a treat, or you’ll get tricked. The privileged class knew they could do little to stop the raucous revelers, just as there’s little to be done should some kids decide to toilet paper your trees or egg your house on Halloween.

THE POPE PULLS A TRICK, WITH OLE ST. NICK

Another hallows eve refrain was dressing in costumes. Often it was the lower class mocking the upper class by dressing and acting like them. Men would sometimes dress as women and women as men. Others would use it as a way to mock religious leaders or politicians.

And it was almost always a rowdy and drunken celebration because one of the substances the merry bands would be begging for was alcohol – usually the cidery punch known as wassail. They’d run door to door and through the streets singing this familiar holiday tune,

Here we come a-wassailing among the leaves so green;

Here we come a-wandering, so fair to be seen.

Love and joy come to you, and to you our wassail, too.

And God bless you and send you a Happy New Year

And God bless you and send you a Happy New YearWe are not daily beggars that beg from door to door;

But we are neighbours' children whom you have seen before.

Love and joy come to you, and to you our wassail, too.

And God bless you and send you a Happy New Year

And God bless you and send you a Happy New Year

This widespread postharvest behavior had been happening for thousands of years. It was so baked into the fabric of society that even the church began painting it with Christian imagery and metaphor. Because the celebrations occurred on or around the end of November and into December there were many elements of Christianity to which they could attach the events.

During Roman times, December 17th marked the day of the Saturnalia – a festival honoring the god of agriculture, Saturn. All work halted for a week as people decorated their homes with wreaths. They shed their togas to dawn festive clothes, and they drank, gambled, sang, played music, socialized and exchanged gifts. It was a celebration of their agrarian bounty and the return of light at Winter solstice. It was also a time to invite their slaves to dinner where their masters would serve them food.

One Christian Saint affiliated with early December – and the one most honored today in the form of a plump jolly man wearing a red velvet suit – is Saint Nicholas. December 6th is St. Nicholas Day. For many European countries this marked the official end of the harvest season. And even today it’s recognized in some countries as a kind of warm-up act to the more official and accepted Christmas day, December 25th.

Nicholas of Bari was a Greek Christian bishop from modern day Turkey. Also known as Nicholas the Wonderworker, he earned a reputation during the Roman Empire for many miracles; all of which, were written centuries after his death and thus prone to exaggeration. But, he was most famous for his generosity, charity, and kindness to children, the poor, and the disadvantaged. He was said to have sold his own belongings to get gold coins that he’d then put in the shoes outside people’s homes. This is the origin of the tradition of putting shoes or stockings out on Christmas Eve.

They say he also saved the lives of three innocent men from execution. He chastised the corrupted judge for accepting a bribe to execute them. You can bet St. Nick would have made sure old-man Rowden had shared his perry before things got too scary.

And he certainly would have been watching over the peasant farmers and slaves to insure they were treated fairly. He seemed to always have an eye out for inequities and justice for common people. Maybe that’s what made him a saint. Or maybe he was just born that way. After all, Nicholas in Greek means “people’s victory.”

DON’T GO HIDING, OFFER GOOD TIDING

The Puritans obviously lost at their attempts to ban Christmas. Lacking any evidence from the Bible, the Christian powers that be eventually settled on the 25th of December as the day Jesus was born. They most likely picked the 25th because that was the day winter solstice landed on the Roman calendar. And while much is made of Christmas day, a certain song reminds us there are actually 12 days of Christmas. Maybe more.

It may feel like Christmas creep when you see holiday decorations appear the day after Halloween, but historically speaking that’s when the party starts. Trick-or-treating kicks off two months of gorging on goodies, making merry with perry, and pleading, pestering, and pining for presents from parents. Just as peasants begged for bounty from their overlords.

Christmas tradition is mostly a months long after-work party that celebrates wealth accumulation while reinforcing a certain economic relationship between the haves and the have-nots. Yes, there are “good tidings to you and all of your kin” and it is a celebration from the heart that can feed the soul with some warm “figgy pudding.”

But lingering under the guise of generosity on the part of the giver is a threat of violence if it’s not shared equitably. “For they’d all like figgy pudding, so bring it out here!” And if you don’t, then “they won’t go until they get some, so bring some out here!”

Maybe think twice before feeling too smug plopping a penny in the Salvation Army’s red pot while making pleasant with a nearby peasant. If your flush with funds this holiday season, and pay people to serve you, be mindful of who you snub.

Tip graciously and share wisely. The ones who deserve it the most, may be the one’s who could do you the most damage. You’d hate for a worker’s revolt where the disadvantaged come knocking on the doors of rich people carrying a yule log, some drunken friends, a bit of angry resentment, and a nearly empty bowl of wassail.

Reference:

The Battle for Christmas. A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday. Stephen Nissenbaum. 1997