Hello Interactors,

This has been an eventful week, but also a week of more extreme heat and smoke. Just when climatologists warned of the certainty of more extreme weather patterns. I’m ready for fall and we’re barely halfway through summer. My plants are struggling too. Does anybody out there know how we’re going to adapt?

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

THE RIGHT TURNS LEFT FOR RIGHTS

Monday of this week, August 9th, was International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. Did you know that? What about Tuesday, August 10th. That was the anniversary of the Pueblo Revolt in what we now call New Mexico. In 1680, the Pueblo people forced 2000 Spanish colonial settlers off their land. Given this was the first example of American people rejecting European rule, some consider this to be America’s first Revolutionary War – nearly 100 years before the more popular version. Oh, and on Wednesday, August 11th my wife and I celebrated our 25th wedding anniversary. But even fewer people know about that historical date.

The International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples was created by the United Nations in 1994. The date honors August 9th, 1982; the first day of meetings for the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations. This group’s mandate was to:

Promote and protect the human rights and fundamental freedoms of Indigenous peoples;

Give attention to the evolution of international standards concerning Indigenous rights.

August 9th celebrates the achievements and contributions Indigenous people have made, and continue to make, to governance, stewardship of the environment, and knowledge systems aimed at improving many of the challenges our world’s environment’s face today.

Indigenous people make up 5% of the world’s population and use one quarter of its habitable surface. But, they protect in reciprocity 80% of the world’s biodiversity.1

The UN defines Indigenous People as:

“Inheritors and practitioners of unique cultures and ways of relating to people and the environment.”2

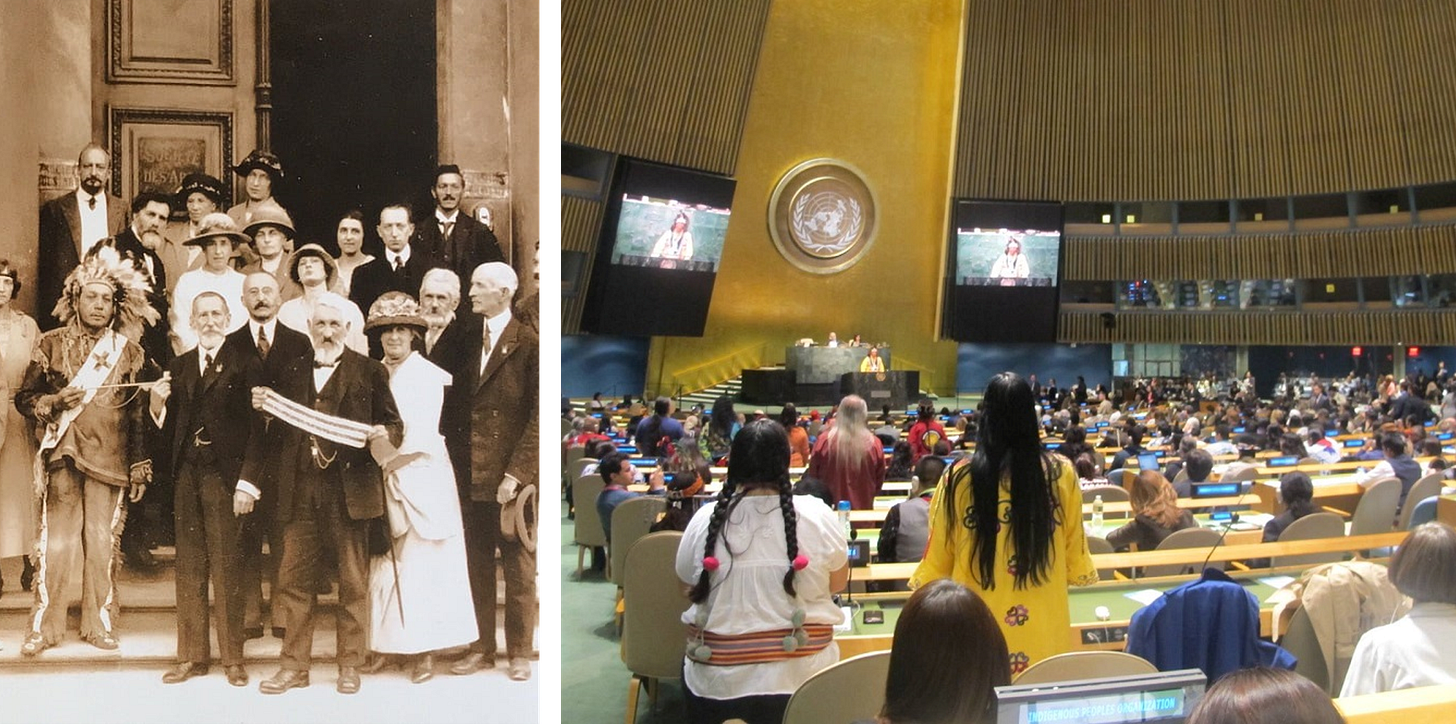

The United Nations’ recognition of the sovereign rights of Indigenous people stems from the International Indian Treaty Council which grew out of the American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 70s. The United Nations recognized the rights of Indigenous people before the United States did. In fact, when the United Nations put the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to vote in 2007, the United States, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia voted against the declaration. They have since reversed this vote, but the American Indian Movement had long recognized the United States was in violation of treaties signed over the last 300 years. So acting as sovereign nations – that happen to reside within a larger, dominant, and controlling nation – they turned to the United Nations for recognition.

Much of the legally binding language used in the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples comes from the legal language written into the original treaties by the United States. Which is why the conservative originalist from the West, Supreme Court Judge Neil Gorsuch, sided with liberals last year in a landmark ruling over McGirt v. Oklahoma. The Supreme Court determined that much of that state was legally ceded to Indigenous people by the United States Federal government two centuries ago and it was high time the country obeyed their own laws. The year prior, Gorsuch did the same in the state of Wyoming. Oddly, the recently deceased Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsberg, a darling of the left, has a mixed record voting in favor of Indigenous people. A 2021 article from Cornell University states,

“During Justice Ginsburg’s first 15 years on the court, 38 Indian law cases were argued. The rights of Indigenous nations prevailed in only seven of those cases. Indigenous nations lost in eight of nine Indian law cases for which she wrote the court’s decision.”

After the Oklahoma ruling, John Echohawk from the Native American Rights Fund – an organization that has spent 50 years fighting for Indigenous rights – was quoted as saying,

“This [case] brings these issues into public consciousness a little bit more…That’s one of the biggest problems we have, is that most people don’t know very much about us.”

It seems Ruth Bader Ginsberg was one of those people.

John Echohawk is following in the footsteps of those who kicked off the American Indian Movement back in 1968, drawing attention to Indigenous rights. Their focus was on the systematic poverty and police brutality toward Urban Indian’s who had been forced off of their land and into cities for generations. This Indigenous grassroots movement rose out of the city that was recently put the international map for its display of obvious police brutality – Minneapolis, Minnesota.

GRANDMA KILLS A CHICKEN

I was not yet three years old when the American Indian Movement was born. I grew up about 250 miles due south of Minneapolis, in Norwalk, Iowa. It’s a suburb of Des Moines surrounded by farmland – much of which is being converted to housing developments. We didn’t live on a farm, but we always had a garden. I wasn’t that keen on gardening as a kid, but I wasn’t shy about eating the beans, corn, and potatoes that Iowa’s rich soil and climate yielded. My Mom’s surefire way to get me motivated to weed the garden or pick beans was to say, “Ok, you’re going to want to eat these beans once their picked, so maybe you should be the one picking them.”

My parents learned to garden from their parents. My Grandma on my Mom’s side always had a big garden. It ran the width of her backyard and was flanked by a dirt alley on one side and a shed on the other. Off to the side of the yard was a rusty barrel I remember being as tall as me. That’s where we’d burn her garbage; now that was a job I enjoyed. I’d haul a bag full of stuff to the barrel, step up on a log nestled next to it, dump in the combustible waste, and drop a fiery wooden match on top of it. Poof. Those trips to the barrel also included carrying a bucket of kitchen scraps into the garden. We’d dig a hole with a shovel, dump the smelly scraps into the hole, and cover it up. Direct injection composting.

My grandparents also kept chickens in the backyard. Our trips to grandma’s house on Sundays usually included a fresh chicken from her yard and vegetables from her garden. She’d walk out back, chase down a chicken, wring its neck, chop its head off, and get to pluckin’.

Occasionally, my uncle Bud would show up with a pheasant or two (or three) strung out in his trunk, shot with his shotgun on his way to grandma’s house. I was always careful to avoid eating the lead shot dotting the glistening meat like embedded peppercorns. In the summer, dinner ended with a bowl of fresh berries and cream from a cow just down the road. But most of the time, it was pie. My grandma made a pie – using lard for the crust – almost everyday until the day she died.

My grandparents on my Dad’s side had a garden and a few apple trees too. My Dad was born in the depression into a family with 11 siblings in the same town my Mom was born. He and his brothers and sisters lived off of the eggs from the chickens they kept. In the dead of winter, they’d hunt squirrels and hang them from the clothesline in the backyard where they’d freeze stiff; more protein to feed hungry mouths during Iowa’s harsh winters. My grandma Weed made a loaf of bread everyday to feed all those hungry tummies.

I am one generation removed from that lifestyle and I’m having trouble keeping a single pepper plant alive. My parents were not farmers, and we did not hunt, but they had learned how to grow and hunt enough food to keep a family alive. Sure their childhood tables were also augmented with store-bought foods, but there was a concerted effort to grow, eat, can, and store as much food as possible. That desire and knowledge seems to get lost with every generation.

Many of the techniques my parents and grandparents used to grow food was taught to them by their European ancestry – knowledge that was passed down from generation to generation. Settlers settling farms and homesteads across America brought with them agricultural methods taught to them in their European homeland. One such convention are rows of segregated crops; a row of beans, a row of squash, and a row of corn, for example. But that’s not how those crops were being grown by people they found here already farming this land.

THREE SISTERS SHARE

Colonial settlers were clueless as to what to do with corn when they first arrived. The locals did teach them to farm corn, a plant first domesticated 10,000 years ago by the Indigenous people in what we now call Mexico. But, in return, some puritanical settlers thought they could show these folks a thing or two about farming. Dismayed by the untidiness made from the climbing clumps of squash at the base of corn stalks gently strangled by spiraling bean vines, the settlers went about mansplaining how to properly plant plants in neat tidy rows – one for corn, one for beans, and one for squash.

But it turns out planting each of these crops to grow alone yields fewer ears of corn, beans, and squash. What the native farmers had learned over those 10,000 years is that when you plant these three plants next to one another, they uniquely help each other above and below ground to grow and prosper. Native people call this method of planting The Three Sisters and it was often planted in waffle-like gardens that create gridded microclimates.

The first sister born is corn. It peaks its head out of the soil in the spring and shoots up straight like a pole. With enough growth to stand on its own, sister bean is born. Bean vines quickly start swirling in circles in search of something to cling on to – like a blindfolded kid playing pin the tail on the donkey. It latches onto the knees of it’s older sister, corn, and they grow toward the sun together. Then comes baby sister squash, crawling along the ground eager to choose its own path in the shadows of its older siblings.

The baby sister, with its broad abundant leaves, helps shade the soil trapping water destined for the three sister’s roots in its water retaining waffle divot. It also keeps sun from tempting pesky weeds from popping up. All three sisters need nitrogen to grow, but lack the ability to siphon it from the air – despite the fact our atmosphere is made up of 78% nitrogen gas.

What these Indigenous people learned over centuries of ecological observation and experimentation is that beans are the secret to providing the missing nitrogen. And Western science has proved it by providing the tools necessary to observe and understand the microscopic biological mechanisms that allow this genesis to unfold. Indigenous people knew it to be true, and Western science allowed it to be seen and described in consistent, repeatable, mathematical, and physical terms that transcend languages, cultures, and geographical boundaries.

What we now know is that nitrogen comes from a fastidious underground bacteria called Rhizobium. It loves to make nitrogen, but only under special conditions. For starters, it needs to be free of oxygen. Given soil is filled with oxygen, it needs to find a suitable host willing to provide an oxygen free environment. As sister bean sends her many roots in all directions it invariably encounters the lingering Rhizobium nodules. Through microscopic chemical communications, the two strike a deal. In exchange for the much needed nitrogen, the bean root provides an oxygen-free nitrogen manufacturing facility for the bacteria; the benefactors of this underground nitrogen source are not only the beans, but her sisters, corn and squash, as well.

I learned all this from Robin Wall Kimmerer, a Potawatomi tribal member as well as the Distinguished Professor of Biology and Director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, at the State University of New York. She sums up this symphony of familial biological reciprocity in her landmark book, Braiding Sweetgrass, with a lesson for us all – not just plants. A lesson taught and practiced by Indigenous people for generations. She writes,

“The most important thing each of us can know is our unique gift and how to use it in the world. Individuality is cherished and nurtured, because, in order for the whole to flourish, each of us has to be strong in who we are and carry our gifts with conviction, so they can be shared with others. Being among the sisters provides a visible manifestation of what a community can become when its members understand and share their gifts. In reciprocity, we fill our spirits as well as our bellies.”

There was one more big event this week from another UN organization called the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). This is a team of climate researchers from around the world and they came out this week to report what they’ve been saying all along about climate change, but this time with an unequivocal warning. The extreme weather events we’re experiencing is indisputably caused by humans. Oh, that’s us. Past reports have used words like may and could but scientists have tossed away their gloves and came out swinging this week. We’re in trouble and it may not be reversible.

Three years ago I ripped out my lawn and planted drought tolerant succulents. Well, the raccoons had the idea first I just went along with it. When the Northwest had its hottest June on record, the sun sucked the life out of plants that are naturally equipped to withstand prolonged heat. Some of the leaves didn’t just shrivel, they nearly evaporated. My backdoor neighbor’s peppers looked like they had roasted on the vine.

On Wednesday night I was talking to a restoration ecologist who works for the City of Kirkland. He organizes teams of volunteers across the city to help eradicate invasive species and plant natives in their place. When I asked him about one park filled with tall lush cedars and firs along Interstate 405 that also features a mining pit at one end where the state dug for gravel to build the freeway, he talked of the struggles getting plants to grow on this compromised soil. He went on to explain how they’ve decided to pick a species that can handle not only the rocky soil, but also the increasing temperatures in Western Washington. So they’re trying a tree more commonly found on the more arid side of Washington state, the ponderosa pine.

One of the big takeaways in listening to Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book is that while we humans have a way of beating ourselves up over the damage we’ve caused the environment, we also have the capacity (and the obligation) to help heal it. When we care for the earth, it cares for us in return in a symbiotic act of reciprocity. Indigenous people figured this out eons ago and the hubris of “Enlightened” European colonial settlers regarded their ways as “savage”. I’m not advocating for some romantic pastoral nirvana where we all trade our homes for huts, tend to our own chickens, and live off the land. But I do believe we live among millions of people who possess ancestral knowledge that, when paired with modern science and technology, could yield a more fruitful outcome. Many cultures living together on the same soil exchanging nutrients and knowledge in an act of reciprocity that benefits us all as individuals and as a global community faced with few alternatives for survival.

Ibid