Hello Interactors,

My wife and I took our daughter on a trip down Interstate 5 earlier this week so she could tour the University of Oregon. It’s a beautiful lush campus in a funky college town that is speckled with fancy new structures financed largely by Nike founder and alum, Phil Knight. Upon the completion of the new track stadium last year, his total contributions to the school is nearing one billion dollars. Where did it all come from?

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

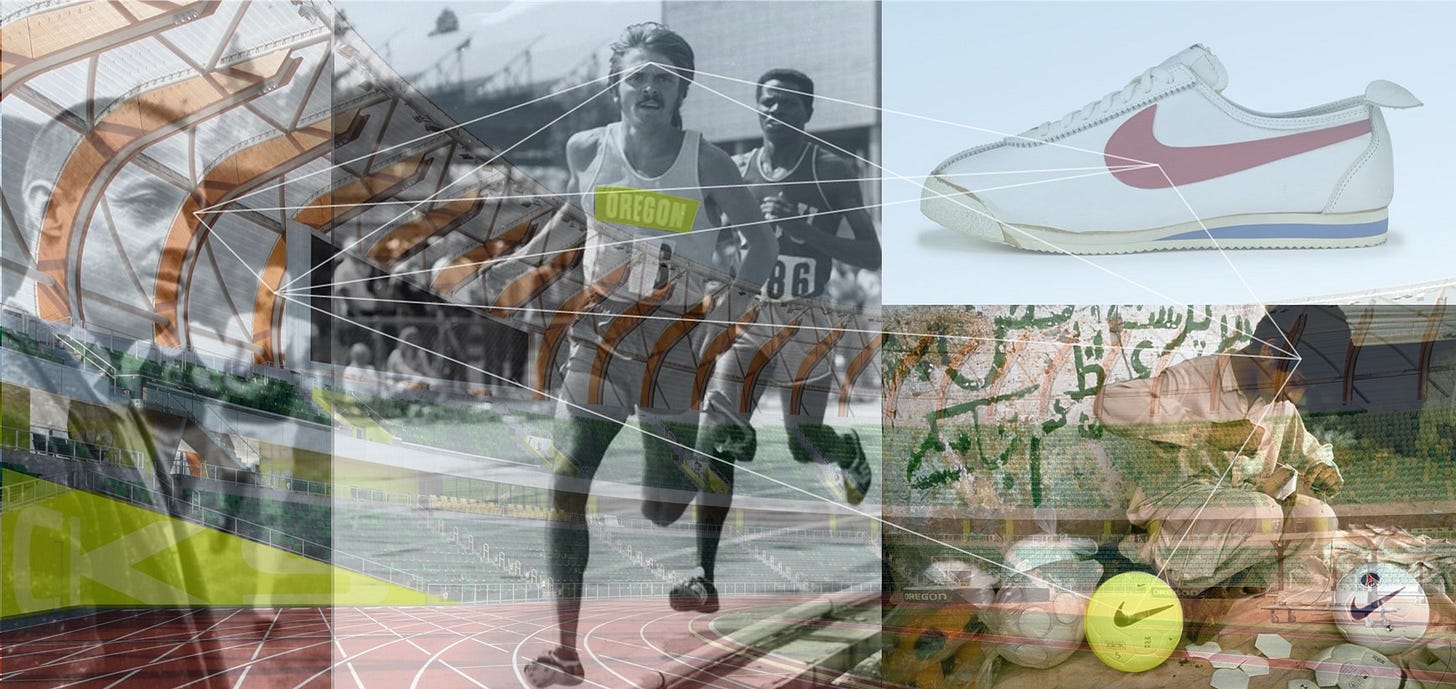

TIGER TRACK TREADS

He dominated his races. He’d jump far in the lead at the sound of the gun challenging his competitors to keep up as his fans chanted “GO PRE, GO PRE, GO PRE”. They’d often be wearing the pervasive shirts that said the same. At the end of one race he grabbed a shirt from sarcastic fan and stretched over his sweaty chest for his victory lap; it read, “STOP PRE!”

Running for the University of Oregon between 1970-1973, Steve Prefontaine never lost a collegiate race in the 3 mile, 5,000 meter, 6 mile, or 10,000 meter events. But internationally he wasn’t so fortunate. He came in a disappointing fourth at the 1972 Munich Olympics in the 5K. Afterwards he said,

“I felt exhausted. They didn't allow me to run the race the way I had planned to, I was chasing them all the way."

He lost three times in his senior year in the one mile event. This same year he challenged the Amateur Athletics Union (AAU) that ruled athletes representing the United States at the Olympics must not receive payment or be endorsed. Prefontaine, a charismatic athlete on and off the track, grew huge crowds wherever he ran. He knew companies would benefit from his abilities, so why shouldn’t he? He also knew he was receiving free shoes and clothes from another Eugene legend – Nike.

By the mid-70s Nike was a decade old and was just getting rolling. Prefontaine’s coach, Bill Bowerman, was the co-founder and a legend in his own right. Preferring to be called teacher instead of coach, Bowerman taught 33 Olympians, 38 conference champions, and 64 all-Americans in his 24 years as head coach. He retired at the end of Prefontaine’s senior year. One of his runners was Nike founder, Phil Knight.

Knight was a middle distance runner at the university until graduating in 1959. While he ran a respectable personal best of 4 minutes 13 seconds, he was not the best runner on the team. Which made him a good candidate for testing the shoes his coach was experimenting with.

Bowerman was obsessed with athletic performance and was frustrated by the poor quality of American running shoes. So, he made his own and asked his athletes to be subjects in his experimental pursuit of the perfect shoe. Sometimes they’d make their feet run faster and sometimes they’d make them bleed. Bowerman didn’t want to risk injuring his top runners, so Knight was often a subject.

The shoe fetish must have rubbed off on the young Phil Knight. After graduating from the University of Oregon he went on to get his MBA at Stanford. There he learned how Japanese companies were overtaking the camera market from Europeans and wrote a paper about how they were about to do the same for the shoe market.

After earning his MBA in 1962, he worked as an accountant while tinkering on the weekend with the idea of being a shoe distributor. He hopped on a plane to Japan to visit shoemaker, Onitsuka after seeing their Tiger brand at the Olympics. He presented his Stanford paper and they were impressed. They wanted to break into the U.S. market and saw this as their chance. When asked what the name of his company was, Knight invented the name on the spot recalling the ribbons he had won competing as a kid – Blue Ribbon Sports.

In 1964 the first shoes arrived and Knight sent a couple of pairs to his shoe sorcerer and former coach, Bill Bowerman. The two shook on a deal to become business partners; Phil would run the business and Bill would design a shoe with just the right stiffness. By 1970 Knight was selling Tiger shoes across the country. As the Japanese Tiger shoe started to dominate the U.S. market, Knight cut ties with Onitsuka, renamed his company Nike, asked a Portland State University graphic designer to design the now ubiquitous ‘swoosh’, and grabbed Bowerman’s first attempt at a Nike shoe, the Nike Cortez.

The shoe was released at the height of the 1972 Olympics after the world witnessed the USA Track and Field team wearing the shoe. Knight and Bowerman made $800,000 selling the Cortez, a 100% increase over selling the Onitsuka Tiger. In 1980, the year they went public, Nike already had 50% of the U.S. market. Today the company is valued at $32 billion and is the largest supplier of athletic equipment in the world.

PHIL AND BILL SPLIT THE BILL

Phil Knight and Bowerman’s success are now enshrined in what I claim is the most beautifully designed sports facility in the country – Hayward Field in Eugene, Oregon. Eugene is known as Track Town USA because of the success of Bowerman, Prefontaine, and the string of track and cross country athletes the University of Oregon has cranked out over the years. It all happened on Hayward field. A $270 million renovation opened last year and Phil Knight led the funding.

We were just there last weekend on a campus visit with our daughter. You don’t have to look far to see the financial impact Phil Knight has had on that campus. Outside of the oval track crowned jewel he contributed $27 million for a major library renovation that now bears his name, $25 million for new law school building that also endows 27 chairs and professorships, numerous upgrades to the football stadium, $500 million pledged for the Phil and Penny Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, and another $41.7 million for a student-athlete tutoring center. And don’t forget the basketball arena named after his son who died unexpectedly in a scuba accident, the Matthew Knight Arena.

That initial collaboration between Knight and Bowerman led to one of the most successful companies in the world. What they did together is a perfect example of two of the most critical ingredients to a dynamic economy: innovation and entrepreneurship.

Innovation is invention with impact. Bowerman personifies the image of the mad scientist tinkering in the garage in pursuit of the perfect solution. He spent so many hours breathing the toxic fumes emanating from his exploratory rubber compounds that he eventually succumbed to nerve damage. The man who wrote a best selling book on jogging in the 1970s became unable to follow his own advise due to the loss of control in his limbs. He sacrificed the speed of his own feet for the swiftness of others.

Phil Knight was born a competitor and entrepreneur. As a teen his dad refused to hire him at the newspaper he ran. He wanted Phil to struggle to find his own job. So he did. He took a job at his dad’s competing newspaper running seven miles each way to get to work. In graduate school he had a sixth sense that the Japanese approach to product development was worth emulating.

He was also savvy enough to make sure his partnership with Bowerman gave him a 51% stake in the business and Bowerman 49%. He knew he could use that leverage to make sure it was a business they were running and not laboratory for running shoes.

ECONOMOUS ANONYMOUS

The role of place should not be overlooked in their collaboration. Economic geographers point to the trust and norms that develop between individuals through close collaboration among local social networks. Personal relationships don’t adhere to a higher order economic structure, they emerge from an accumulation of shared knowledge and passion that increases the potential for innovation.

The idea stems from the great economist Karl Polanyi. In his landmark 1944 book, The Great Transformation, Polanyi gives this concept a name: embeddedness. Stanford economic sociologist, Mark Granovetter, reaffirmed the idea in his oft referenced 1973 paper, “The Strength of Weak Ties.”

Phil and Bill were also participating in an act of creative destruction. This term comes from one of the most influential economists of the 20th century, Austrian turned American, Joseph Shumpeter. Shumpeter pointed out that for an invention to become an innovation, it has to have impact through capital investment and also lead to the rise of new businesses. Blue Ribbon Sports started in Bowerman’s garage with a rubber sole made from his wife’s waffle iron and a $500 loan from Knight’s dad. But as Nike they outsource manufacturing to factories around the world, thus avoiding having to spend capital dollars owning a single building or piece of equipment.

Had these two been tinkering in Eugene two or three decades earlier, it’s likely Eugene would have become the Detroit of athletic equipment and apparel. Known in economic circles as Fordism, Henry Ford perfected the practice of building mass produced products systematically using locally sourced labor, usually men, who could theoretically earn enough to afford the products they were assembling. This wasn’t always the case. Women, especially women of color, were often forced to take side jobs to make ends meet.

But Nike was emerging in the Post-Fordist era of the 1960s and Phil Knight had already clued into the manufacturing advantages Japan had pioneered after WWII. In post-war Japan, the government played a critical role in shaping their industries. They controlled imports and exports, but also “national systems of innovation” by creating “formal and informal institutions” to facilitate the “coordination and promotion of technology transfer.”(Economic Geography), A national form of embeddedness.

But as Japanese companies were growing, they were also getting pressure to maximize profits. A popular way to do this is to pay workers less. So during the sluggish stagflation of the 1970s, Japan introduced ‘non-regular employment’; or more generally, the temporary worker. Which, by in large, were, and still are, adult women.

These workers are not only paid less, they “have much less job security than regular employees,” have “no considerable protection from dismissal”, their “average job tenure is significantly lower than for regular employees”, and they “have limited access to on-the-job or formal training and weak career prospects.”1

Karl Marx once noted in the 1800s that capitalism always seeks to eliminate the worker. Nike achieved this by sourcing near slave labor in poor countries so far away from the customer that the worker appears to have been eliminated. They let some poor nameless and faceless woman in a foreign land risk nerve damage making their shoes, so they, or their fellow community members, wouldn’t have to.

Much has been written about the overseas Nike sweatshops since they were exposed in the 1990s. The CBS program “48 Hours” did a piece titled, “Just Do It – Or Else”, where they showed workers in Viet Nam getting swatted over the head by their supervisors for making errors in the stitching of a Nike garment.

Or how about the 1997 New York Times article where they revealed Vietnamese workers were exposed to the odorless carcinogenic chemical toluene at 177 times the legal limit. And who can forget the Life Magazine photo of the 12 year old Pakistani boy stitching the laces into a Nike soccer ball? Just Do It.

FACE THE FACELESS, EMPOWER THE POWERLESS, HEED THE GREED

Seeking cheap labor in regions far away from the eyes of consumers not only hid these exploits from Nike customers, but it absolved Phil Knight of responsibility. By outsourcing capitalism to a faraway land, Nike abstracts it way and disassociates from it. Clemson University political and moral philosopher, Todd May, puts it like this,

“It is of the character of transnational capitalism that the source of economic oppression is often thousands of miles away, separated from those it exploits by many levels of bureaucracy, language, and national borders.”

In 2001 a Nike representative reacted this way to accusations of reported worker abuse, “It’s not within our scope to investigate. We’re about sports, not manufacturing 101.”

Nike has tried to curb these abuses. In 2005, they were the first apparel manufacturer to disclose the names and locations of its nearly 500 plants. They’ve created watchdog groups in many of these locations to monitor progress, but many contractors and subcontractors pack up and move to a different location away from the surveillance.

One effective way to draw attention to these exploits is to empower employees to pool their knowledge, organize, and act; a united worker’s rebellious version of embeddedness.

Companies like Nike can fold up shop at the spur of the moment and find a new supplier. They don’t own the equipment, nor do they have any obligation to the plight of the workers or effects on the local communities. Workers are cluing into this reality and instead put pressure on local, regional, and national governments to do the protesting of exploitive capitalism on their behalf.

Here’s how Thai activist and labor organizer Junya Lek Yimprasert describes it,2

“We found out that the factory and the equipment already belonged to the bank. If the workers were to demand a share of the proceeds of the sale, they would get zero, so they decided to change the strategy. First they would hold the employer responsible; second the government; and finally the brands they had produced for.”

It seems to be working. In Sri Lanka, one union organizer observed,

“Auditors from Nike visited the factory and finally the company recognised our union. It had an impact on all [of the] free trade zones. The Board of Investment governing the zones amended its guidelines to allow for unions and make employers recognise them.”3

Back in the 70s when Prefontaine was squabbling with the AAU, he was demanding athletes be recognized and compensated for their labor. And just a couple weeks ago, Phil Knight helped organize a company called Division Street, Inc., that will help Oregon student athletes monetize their own name, image, and brand.

I can’t help but be impressed with the new buildings and support Phil Knight is lavishing on his alma mater. Especially, the Hayward Field renovation. But I also feel discomfort knowing it all came at the expense of near slave labor at the hands of nameless and voiceless humans, mostly women, tucked away in a sweatshop.

And I’ve grown weary of public universities, and city governments, begging billionaires to throw us some spare change in hopes of making our communities as rich as they are. Celebrating philanthropy, the contributions of great men, and even star athletes only accentuates the socioeconomic malaise that divides us and unsettles us.

I have an idea. What if instead of lavishing the Oregon campus with another chunk of change or fancy building, Phil Knight took a stand. What would happen if, in an homage to Steve Prefontaine’s “STOP PRE” self-effacing sardonic strut, Phil grabbed a shirt from a Nike fan, pulled it over his suit as the crowd chanted “NI-KEE, NI-KEE, NI-KEE”, and he ran a victory lap around Hayward Field in a bright green Nike shirt with neon yellow lettering that read: “STOP GREED!”

New and Enduring Dual Structures of Employment in Japan: The Rise of Non-Regular Labor, 1980s–2010s. Andrew Gordon. Social Science Japan Journal, Volume 20, Issue 1, Winter 2017.

Clean Clothes. A Global Movement to End Sweatshops. Sluiter L. (2009). London: Pluto Press.

Ibid.