Hello Interactors,

Winter break is drawing to a close for my two kids who just wrapped up their first semester at college on the east coast. We’ve had a lot of conversations about what it’s like living in a new city. My daughter is particularly impacted having moved to New York City from a relatively small town near Seattle. But she’s not alone. More and more people are moving to urban areas, but does it necessarily make them happier?

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

BIG CITY, LITTLE PRETTY

Stepping out our front door with my daughter who was just home from New York she proclaimed, “It’s nice just walking out the door and seeing trees. No twenty-story elevator trip, no concrete, no noise, no high rises, no pollution…just easy, calm, and quiet nature. It’s beautiful.”

She loves the city; she hates the city. I asked her what New York could do to make it more pleasing, she recommends more green spaces. More Central Parks. Humans do need nature; some more than others.

I’m reminded of my philosophy professor at UC Santa Barbara for an aesthetics class. It was his first-year teaching and first-time outside of New York. There he was on one of the most beautiful coastline campuses in the world buttressed by green foothill mountains. He was shocked to learn his student’s thought nature was ‘beautiful’. He didn’t get it. Or so he claimed. He kept quoting Woody Allen who complained about not being able to sleep in the country because it was too quiet. Allen once quipped, “I am two with nature.”

Some proclaim “cities; can’t live with them, can’t live without them” while others groan, “Nature; can’t live with it, can’t live without it.” More and more people are choosing to live with cities, not nature. The United Nations estimates 55% of the world’s population live in urban areas. It’s estimated that number will grow to 75% by 2050.

The rate of growth varies by country or region as does the share of the total population. Japan is the most urbanized, United States is number two, followed by Europe. But number four has the fastest urbanization growth rate – China.

But what constitutes an urban area? Don’t ask me. I screwed up my poll last week by providing widely inconsistent ranges of population size. It turns out I’m not the only one confused about quantifying urban areas. Despite the U.N. making claims and predictions about urbanization, there is no agreed upon definition of an urban area. Japan says it’s 50,000 people or more while Sweden says it’s 200. Singapore’s entire population is considered urban while Uruguay leaves it up to the city to decide whether it’s ‘urban’.1

Either way, the trend is clear. More people are moving to urban areas than ever before. Even my ill-formed poll of Interactors shows most live in bigger and the biggest metropolitan areas. And I just dropped my daughter off at the airport where she’ll soon be back in the city and away from nature.

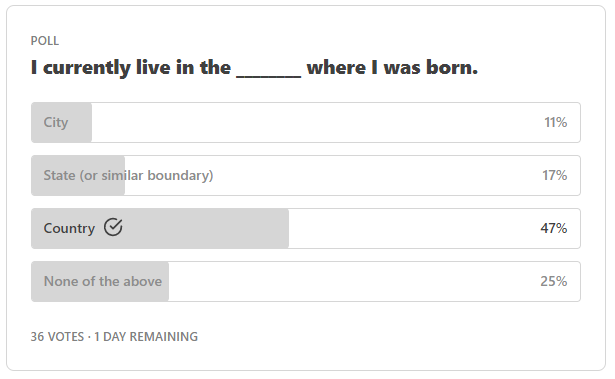

Why are so many people choosing to live in large cities? Are they happier? Most of the 36 Interactors responding to my poll report being happy. And most have moved to seek happiness. About half of the 36 responders still live in the country in which they were born (47% or about 17 people), a few live in the same state or similar (17% or about six people), and even fewer live in the same city (11% or about four people). Another 25%, or about nine people, have moved to a different country all together.

People move. It’s a defining characteristic of our species. We move to satisfy our basic human needs. However, there’s also disagreement over what constitutes ‘human needs.’ What explanations do exist are largely defined and propagated from a Western perspective from the study of WEIRD people (Western (mostly White) Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic).

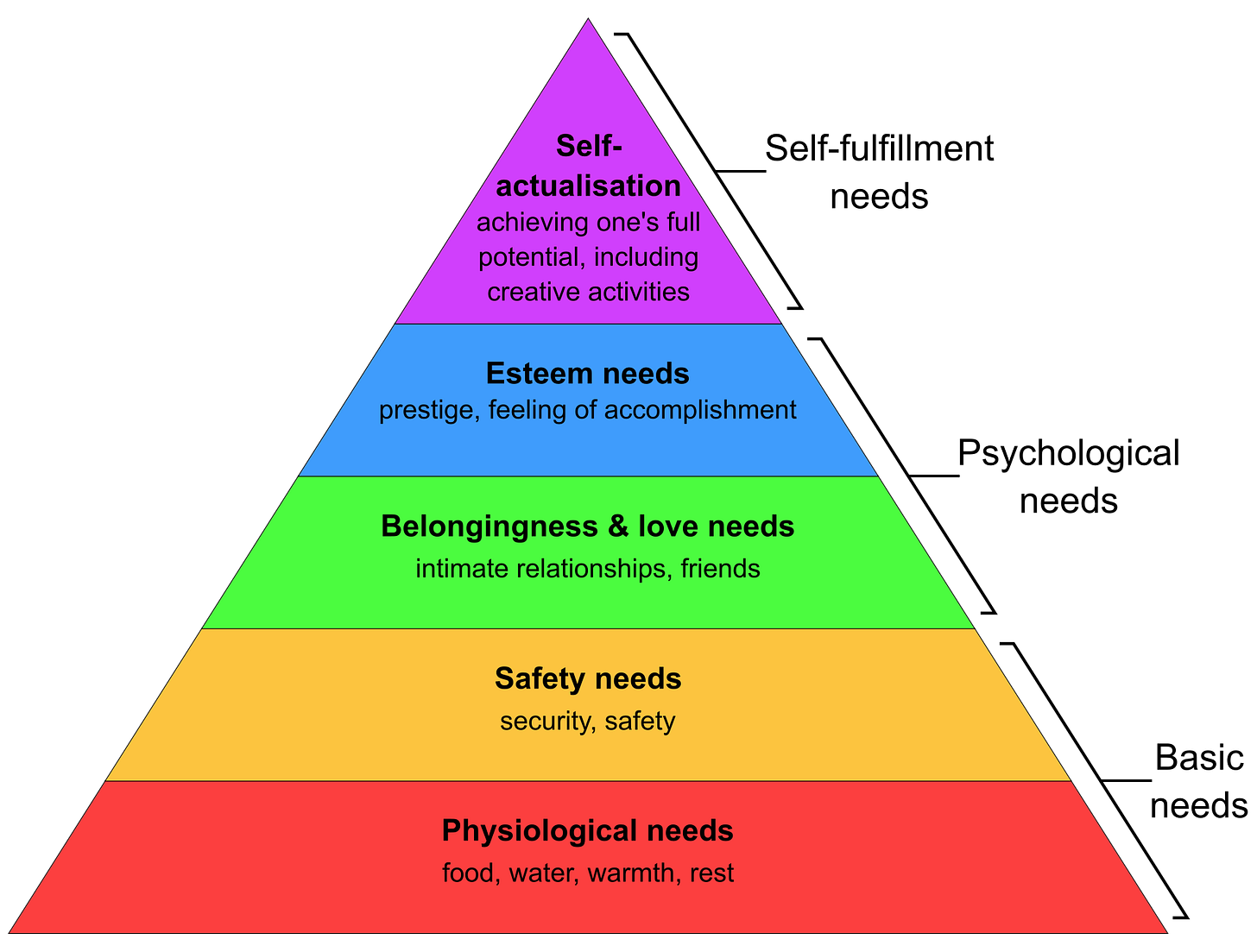

One of the most popular and enduring needs models comes from a simple pyramid drawn by the American psychologist, Abraham Maslow. His ‘hierarchy of needs’ posits that human needs are built on top of one another going from ‘physiological’ needs like breathing, food, and water to ‘safety’ then ‘love and belonging’ to ‘esteem’ and finally ‘self-actualization.’ But is this an oversimplification? Is it just an easy-to-understand graphic that puts the lofty concepts of ‘morality’, ‘creativity’, ‘spontaneity’, ‘problem solving’, and ‘acceptance of facts’ at the top of a mountain of over-achievers? Is the hierarchical path to happiness achieved only by those with ‘confidence’, ‘respect of others’, and high ‘self-esteem’?

Does one really need ‘security’, ‘employment’, and ‘property’ to have a happy life filled with loving ‘friendship’ and ‘family’. Some families moving to cities risk physical and psychological security, induce precarity by change jobs, and pay rent on the most affordable apartment they can find – all to satisfy basic physiological needs. But are they not creative, spontaneous, problem solvers who may indeed be happier than before their move? Must everyone earn ‘achievement’ awards or the ‘respect of others’? Must they exude ‘confidence’ to be happy?

It seems Maslow treated needs as a series of hierarchical problems to conquer. One must climb a particular ladder of self-actualization rung by rung. It’s a convenient pseudo-psychological symbol to American idioms like ‘climbing the corporate ladder’, ‘upper class’, or ‘keeping up with the Jones’s’.

A NEED FOR A BETTER CREED

Like the word ‘urban’, there is not one definition of ‘human need’. But with so many people flocking to cities, the running assumption among most, including researchers, is that people do so to become wealthier, healthier, and happier. But are these still biased toward climbing some kind of economic ladder? Are they held up by surrounding socio-political systems, structures, and norms largely fueled by Western capitalistic ambitions? Yes, certain amounts of wealth accumulation are needed to satisfy basic needs, but are there hidden assumptions that more money buys more happiness? Were the Beatles wrong? Does money really buy love? What is required to satisfy our needs?

Experts generally agree on these four categories of human need: personal, economic, social, and political.2 We all require certain physical and psychological safety in pursuit of our goals and happiness. How we interact with people and place plays a vital role and is dictated by the social and economic systems influenced by politics. Increasingly, it appears more and more people seek places that most complicate these requirements – cities. So, is widespread urbanization making people safer, healthier, richer, and happier?

It varies, but in the aggregate, more humans are safer, healthier, wealthier, and presumably happier than in the known history of civilization. And as countries become richer, they also become more urbanized. As cities increase in scale, as with biological systems, naturally occurring scaling laws dictate they also become more efficient. When an animal doubles in size, it’s operating efficiency more than doubles – about 15% more.3 When a city doubles in size, it also gains from scaling efficiencies. Wages, innovation, and infrastructure, for example, all more than double with population size. These efficiencies tend cities toward better sanitation, water quality, cleaner fuels for cooking, and better nutrition – all requirements to fulfill basic human needs.

However, these positive effects are not evenly distributed, and the wealth correlations found in the aggregate may be due to inequalities. Large cities can yield and attract extreme wealth giving the illusion bigger is better and wealthier is healthier. As most everyone witnesses, if not endure, urban areas are also home to extreme poverty, accentuated inequalities, and politicians in search of a cure.

Indeed, those same geometric power laws that can more than double the positive effects of cities can also more than double crime, garbage, illness, and disease. Which has people yearning for quiet, natural spaces inside and outside the city, just like my daughter.

Access to nature seems to be a basic human need hidden from the surface of Maslow’s pyramid. It sits under a category of needs my old philosophy professor may have an issue with – aesthetics. Nature features more prominently on a competing model of basic human needs made by the Chilean economist Manfred Max-Neef.

He was Frustrated by the negative social effects influenced by the U.S. backed conservative economic policies of the so-called “Chicago Boys”. This was a group of Chilean economists trained at the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman on conservative neo-liberal philosophies and policies. They went on to hold prominent positions under the military dictatorships of Chile in the 1970s and 80s. Max-Neef lived with and studied those stricken by failed attempts at fashioning the Chilean economy after American neoliberal forms of capitalism. He observed the negative effects of debt and ecological destruction brought on by privatized economic and social systems modeled after and funded by the United States and top U.S. corporations.

After decades of experience and research living and traveling around South America in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, he wrote a book in 1989 on Human Scale Development. It centers on the organic and messy human needs diagnosed at street level in contrast to the clean, mechanistic, and abstracted top-down, state and/or corporate led approach. Max-Neef’s findings became foundational to what we might now call ‘urban sustainability’. In 1992, in the publication Real-Life Economics: Understanding Wealth Creation, he published a human needs framework that shuns the strict hierarchical structure of Maslow’s while adhering to those needs scholars largely agree exist among humans.

Max-Neef identifies nine needs: subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, leisure, creation, identity, and freedom. These fall under these four categories that define our existence: being in psychological state, having assets, doing actions, and interacting with and in places with or without other people. Because cities increase chances of social interaction, offer more opportunities for doing actions in exchange for money, the opportunities to have assets increases, leading to a desired state of being.

WINGS OF A BUTTERFLY

Max-Neef observed that while human needs are universal, getting them satisfied is contingent on particularities of a given city and how it functions. For example, a well equipped and staffed police force may satisfy the fundamental human need to feel safe, but it can also limit freedoms, perpetuate unfair power inequities, or dissuade community interactions.

But for Max-Neef, community engagement and participation between the powerful and the powerless was at the heart of satisfying the needs of all humans. He was interested in practical solutions to problems at scales ranging from neighborhoods to cities and regions to countries. Thus he devised his model to be flexible and adaptable to unique situations at the micro and macro level – each dependent on the other.

A group of Dutch urban studies researchers recently published a paper calling for planners and elected officials to consider the Max-Neef model as a guide. They reveal how it’s uniquely suited to better plan and shape or reshape cities toward a more just, equitable, and environmentally sound future. This is due mostly to the synergies between fundamental human needs and the elements of cities that can satisfy them.

But it would be wrong to say these associations and synergies necessarily guarantee the satisfaction of needs. Simply moving to a city, with all it’s social potential for interactions, does not automatically lead to a better life. Max-Neef says,

“The articulation between the personal and social dimensions of development may be achieved through increasing levels of self-reliance. At a personal level, self-reliance stimulates our sense of identity, our creative capacity, our self-confidence and our need for freedom. At the social level, self-reliance strengthens the capacity for subsistence, provides protection against exogenous hazards, enhances endogenous cultural identity and develops the capacity to generate greater spaces of collective freedom. The necessary combination of both the personal and the social in Human Scale Development compels us, then, to encourage self-reliance at the different levels: individual, local, regional and national.”

But he also warns it is not his

“intention to suggest that self-reliance is achieved simply by social and economic interaction in small physical spaces. Such an assumption would do nothing but replicate a mechanistic perception which has already been very harmful in terms of development policies.”

Instead, he calls for

“Complementary relationships between the macro and the micro, and among the various microspaces, [that] may facilitate the mutual empowering of processes of socio-cultural identity, political autonomy and economic self-reliance.”

This requires government systems to flexibly empower individuals and local communities so they may satisfy their basic human needs as they see fit. Instead of a rigid top-down, mechanistic, hierarchical system geared toward economic growth and private wealth accumulation, a more flexible system spanning many nested hierarchies is required that fosters personal growth in the pursuit of human needs. A system that is resilient to the variability of external forces. Like a pandemic.

The pandemic appears to have changed all the historic economic, cultural, and political assumptions surrounding the physical social interaction of people in cities. With more and more people working, socializing, and shopping online what are the implications for the social aspects of human needs? Last summer, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics published the results of their 2021 American Time Use Survey. On days “employed persons” worked, 38 percent did some or all their work at home and 68 percent did some or all their work at their workplace. In 2019, before the pandemic, workers were 24 percent less likely to work at home and 82 percent more likely to work at their workplace.

Workers 25 years old and older with an advanced degree were more likely to work at home than those without. Sixty-seven percent of those with an advanced degree worked at home versus 19 percent with a high school diploma and no college degree. Will those advanced degree earners get their human needs fulfilled working from home? Is online social interaction better or worse at fulfilling basic social needs or are those getting fulfilled outside of work hours? Will those without college degrees find that interacting physically offers more opportunities for doing? Will they find the necessary opportunities to have the necessary assets needed for a desired state of being?

My daughter goes to school in the center of one of the biggest cities in the world and my son in a sparsely populated wooded suburb. As they finish their first year of college, I wonder what they’ll face a few years from now as they seek to fulfill basic human needs on their own. Will cities and governments morph to meet to what appears to be one of the most transformative moments in the history of urbanization? How much adapting and compromising of their desires will be required to satisfy their basic human needs?

One thing is clear, and Max-Neef seems to have gotten this right. While macro-scale political and economic systems may appear to muster control over people, it took a pandemic to reveal the power of individual micro-scale behavior. It seems when most of those individuals with the means to chose how to work, to do, to have, to satisfy their needs differently, they acted. They chose how to interact with society in a new way that indeed forced large-scale macro changes to worldwide economic, social, and political systems.

What would happen if instead of blindly following the course set by centuries of a particular socio-economic construct, of which increased urbanization is a biproduct, we all chose to act differently? What if instead of feeling the need for speed, we all slowed down to succeed? What if in pursuit of a basic need, we shun the allure of greed? Surety is not decreed and only uncertainty is guaranteed. So, let’s be what we want to be, have what we want to have, do what we want to do, and interact with the world. After all, small acts by a few ripple through and through bringing changes to a world anew.

Urbanization. Our World in Data. Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser. 2018.

The cities we need: Towards an urbanism guided by human needs satisfaction. Rodrigo Cardoso, Ali Sobhani, Evert Meijers. 2022.

Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies. Geoffrey West. 2018.